Point Venus, French Polynesia

Point Venus is the place from which Captain James Cook observed the 1769 transit of Venus.

Description Image Gallery

Geographical position

Point Venus is a peninsula on the north coast of Tahiti.

Location

Latitude: 17°29’41.6" south, Longitude: 149°29’44.4" west. 9 meters above sea level

General description

During Captain James Cook’s first voyage, the transit of Venus on June 3, 1769 was observed from Point Venus on the island of Tahiti. Currently, there is no monument to mark the astronomical observations or monument to Captain James Cook, although there is a monument to the crew of the Bounty, who also landed there, and a Victorian-era lighthouse.

History

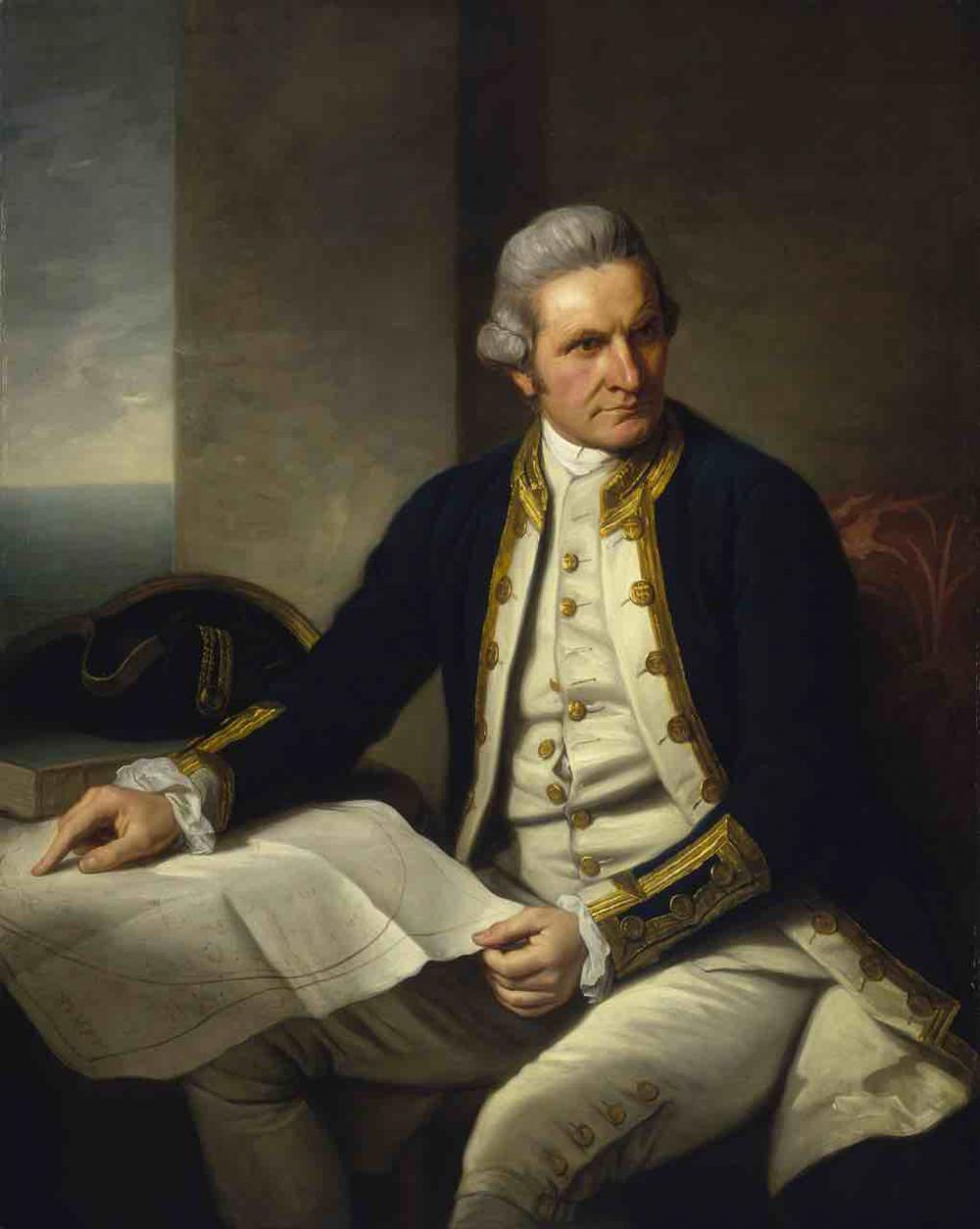

Portrait of Captain James Cook (National Maritime Museum)

The determination of the astronomical unit using Venus or Mercury transits was first proposed by Scottish mathematician James Gregory in 1663. Edmund Halley took up this idea and recommended several places for the observation of forthcoming transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769 in the 1716 issue of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

The observations of the 1761 transit were unsuccessful due to poor weather conditions, so in 1766, preparations began for the 1769 transit.

The Royal Society chose three locations for expedition – the North Cape (Norway), Fort Churchill at Hudson Bay (Canada) and a suitable island in the South Pacific.

British navigator Samuel Wallis made first European contact with Tahiti in June 1767. Upon his return to England, the Royal Society decided that Tahiti would be an ideal location for the observation of the Transit of Venus.

The Admiralty chose HMS Bark Endeavour to take astronomers and other scientists to Tahiti and James Cook was commissioned as Lieutenant and appointed to command the vessel.

The Endeavour departed Plymouth on August 26, 1768. It crossed the Atlantic, rounded Cape Horn and reached Tahiti on April 13, 1769. James Cook commissioned the building of a small fort and an astronomical observatory in preparation for the transit on June 3.

The sky was clear for the observations of the transit and James Cook wrote in his journal:

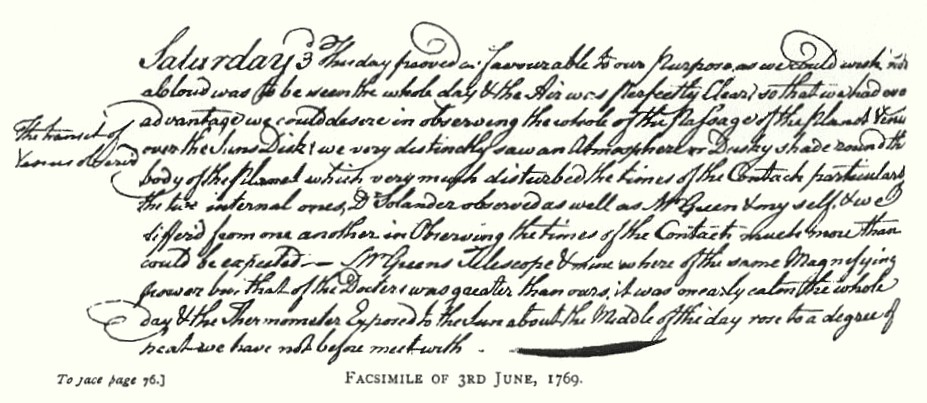

Facsimile of the journal entry for June 3

“This day prov’d as favourable to our purpose as we could wish, not a Clowd was to be seen the whole day and the Air was perfectly clear, so that we had every advantage we could desire in Observing the whole of the passage of the Planet Venus over the Suns disk: we very distinctly saw an Atmosphere or dusky shade round the body of the Planet which very much disturbed the times of the Contacts particularly the two internal ones. Dr. Solander observed as well as Mr. Green and my self, and we differ’d from one another in observeing the times of the Contacts much more than could be expected. Mr. Greens Telescope and mine were of the same Magnifying power but that of Dr was greater than ours. It was nearly calm the whole day and the Thermometer expose’d to the Sun about the middle of the Day rose to a degree of heat we have not before met with.” (Journal of James Cook)

Sketches of Cook’s and Green’s observations from the 1771 issue of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

Once the observations were complete, Cook set sail for the second, „secret“ part of his voyage: to search the South Pacific for signs of the postulated continent of Terra Australis.

The Endeavour returned to England on July 12, 1771. The Royal Society was disappointed with the results of the data, as the so called „black drop effect“ made recording the times of the entry and exit points from the Sun very difficult.

The Royal Society deemed the expedition and the observations a failure, but the value Thomas Hornsby for the 1771 issue of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society derived from the solar parallax from the 1769 observations was that „the mean distance of the Earth from the Sun will be 93,726,900 English miles“ (the modern value is 92,955,807 miles).

Bibliography (books and published articles)

- Orchiston, W. (2005). James Cook’s 1769 transit of Venus expedition to Tahiti. In Kurtz, D.W. (ed.). Transits of Venus: New Views of the Solar System and Galaxy, Cambridge University Press, pp. 52–66.

- Teets, Donald (2003). Transits of Venus and the Astronomical Unit (PDF). Mathematics Magazine, 76(5) (December 2003).

- Herdendorf, Charles (1986). Captain James Cook and the Transits of Mercury and Venus. Journal of Pacific History, 1(21), 39–55.

Links to external sites

- Link to Google Maps

Back to the Astronomical Heritage - Places connected to the Sky

Return to the Places connected to the Sky map/list page.

About the author

Doris Vickers lives in Vienna (Austria)