Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Uraniborg and Stellaeburgum, Sweden

Format: IAU - Outstanding Astronomical Heritage

Description

Geographical position - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:20:02

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Tycho’s observatories, Uraniborg and Stellaeburgum (Stjerneborg), on the Danish Island of Hven in the Øresund between Zealand and Scania (today Ven, Swedish).

Location - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-19 10:02:00

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Uraniborg 55° 54′ 28.3″ N, 12° 41′ 47.7″ E, elevation 44m above mean sea level.

Stjärneborg 55° 54′ 24.7″ N, 12° 41′ 49.3″ E, elevation 42m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 13:26:30

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

---

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 19

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:24:29

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

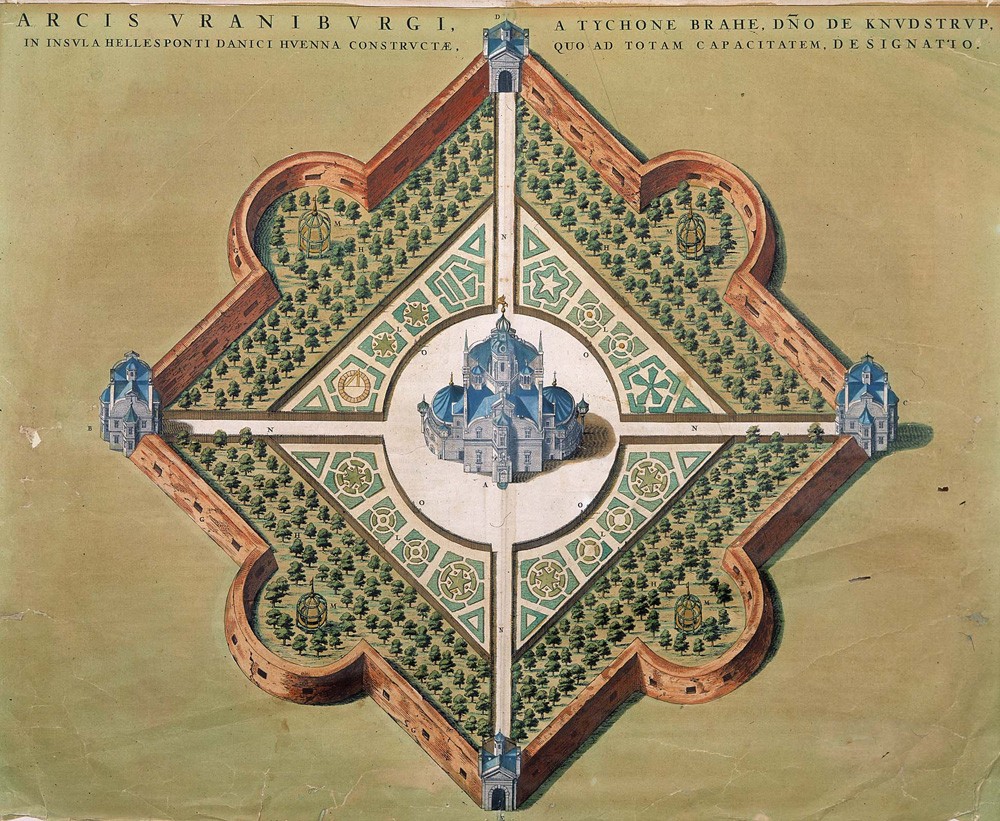

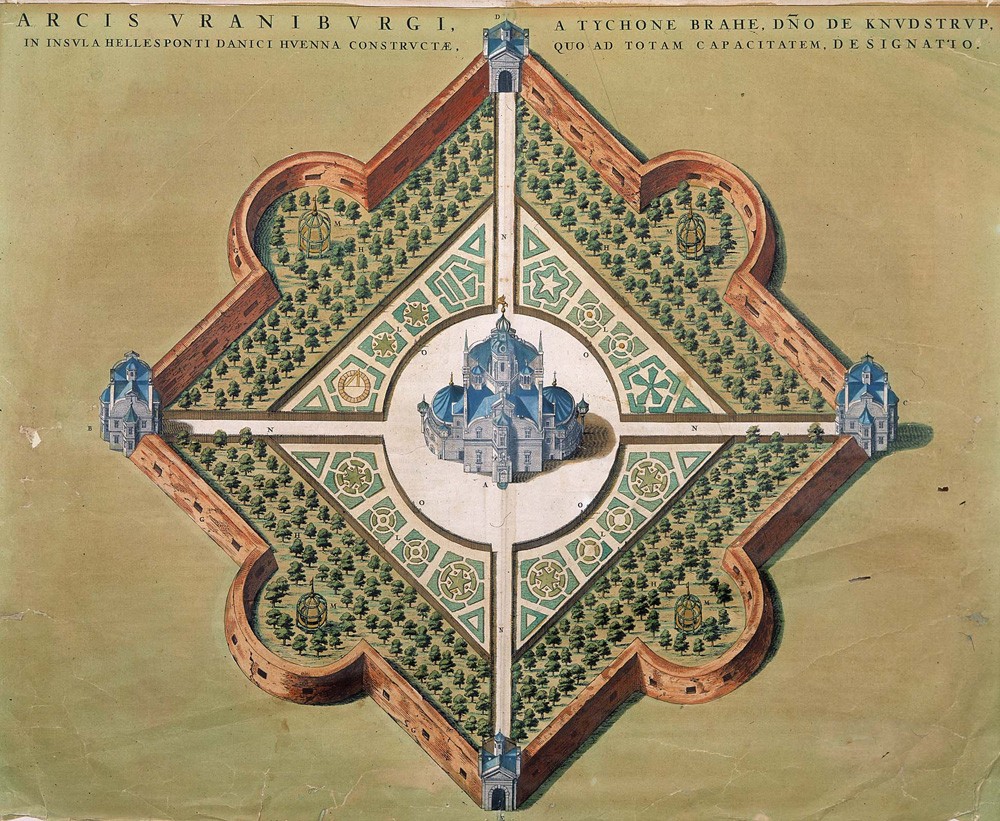

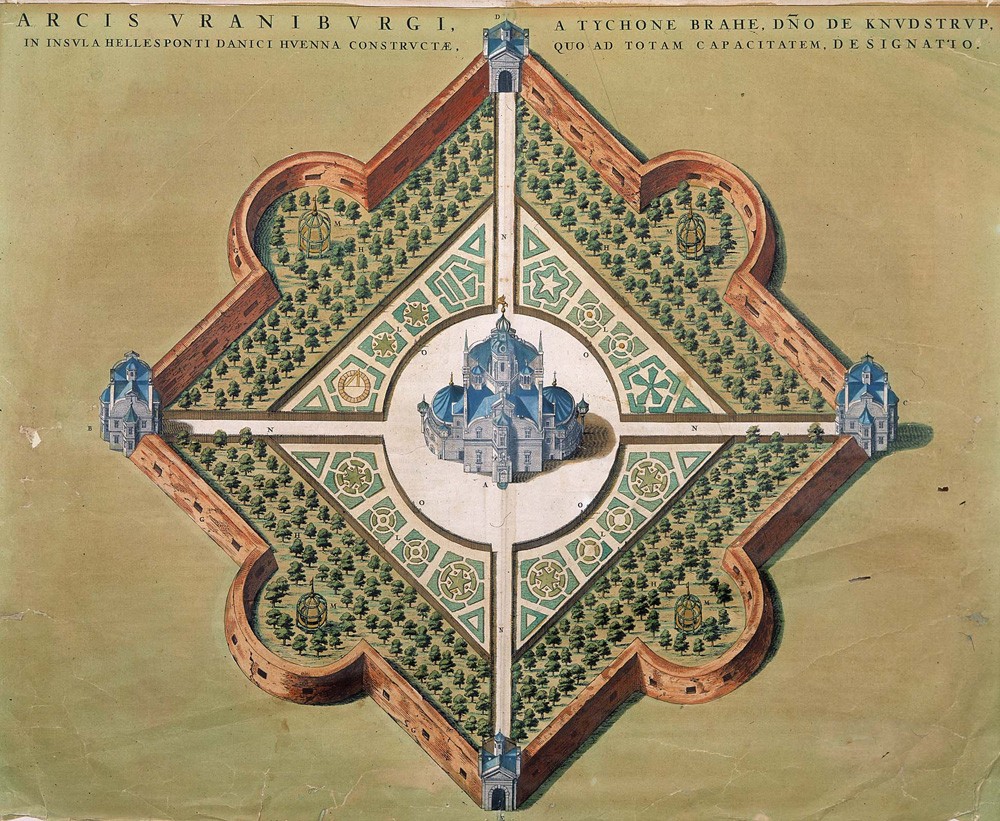

Under the sponsorship of King Frederic II of Denmark (1534–1588), Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) built his observatory, called "Uraniborg", dedicated to Urania, the Muse of Astronomy (Wolfschmidt 2002a) on the Danish Island of Hven (today Ven, Swedish). It was the first time that a building was erected in Europe especially for the purpose of astronomical observations.

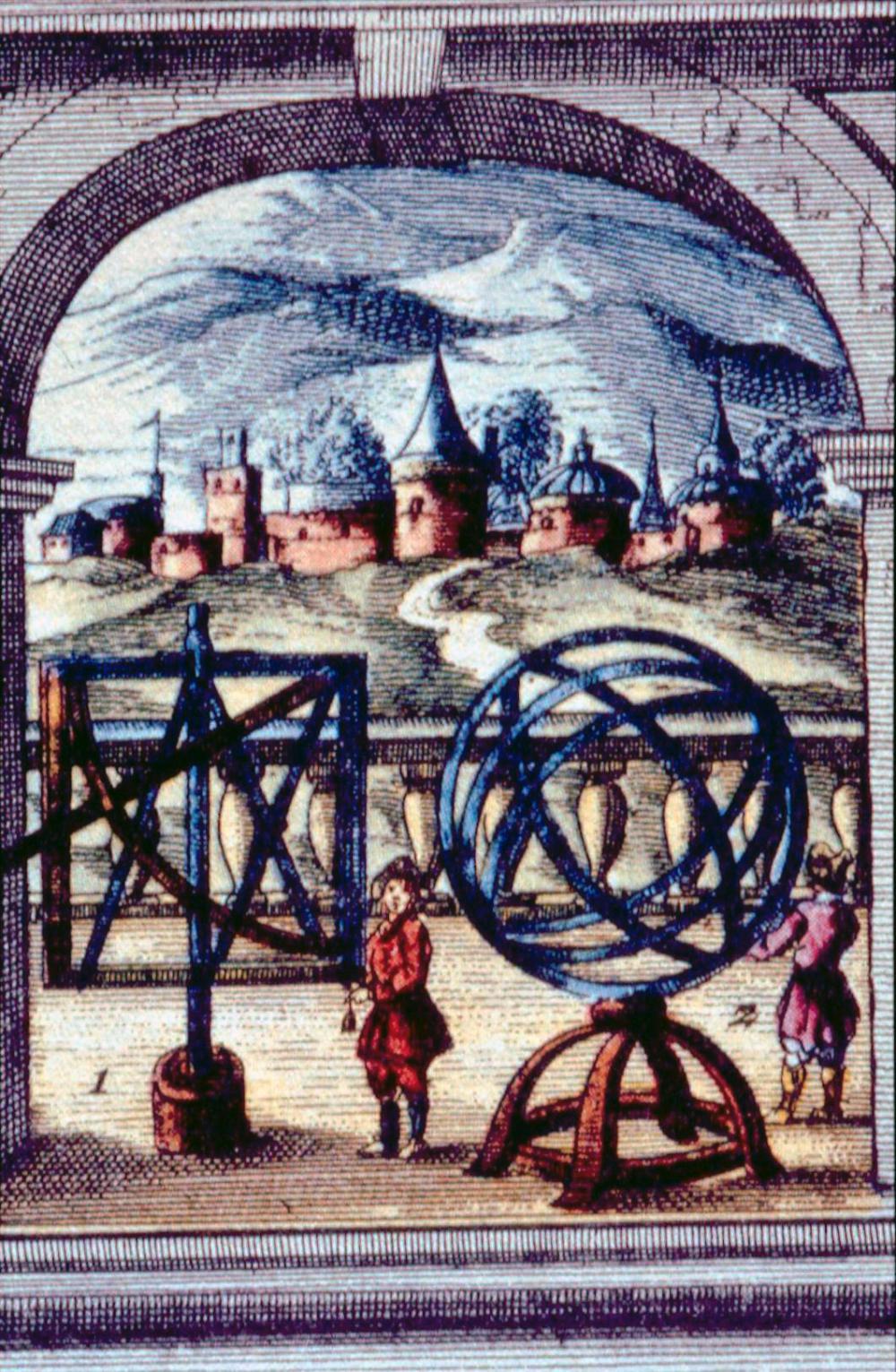

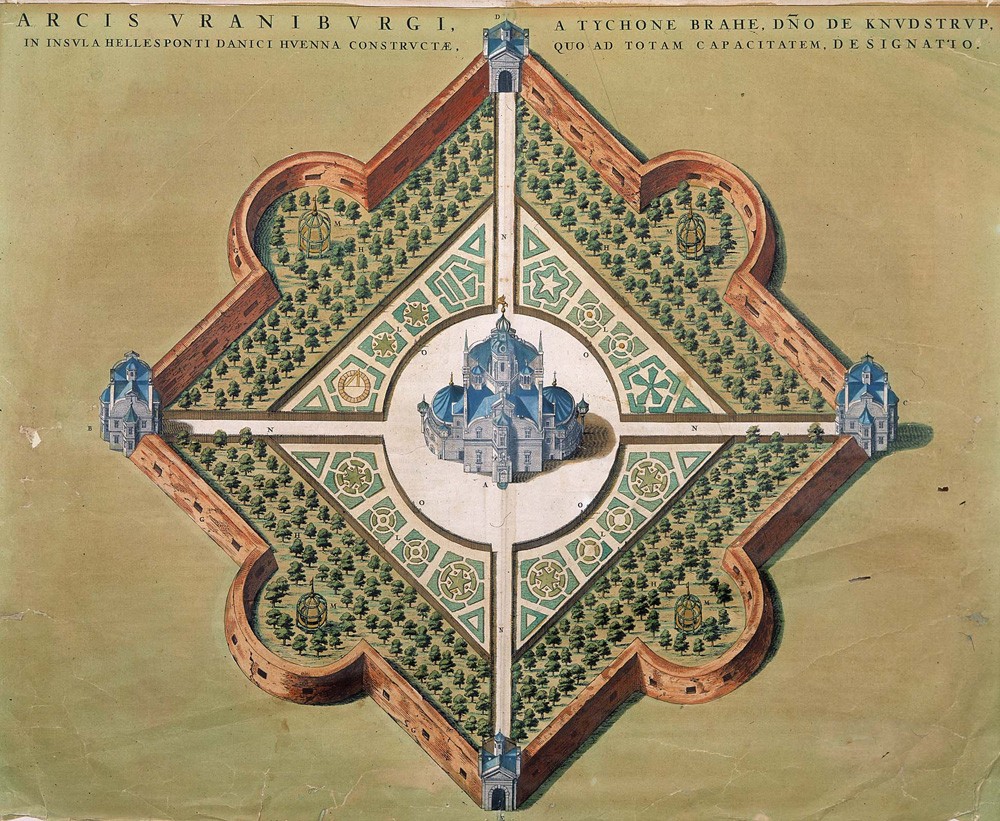

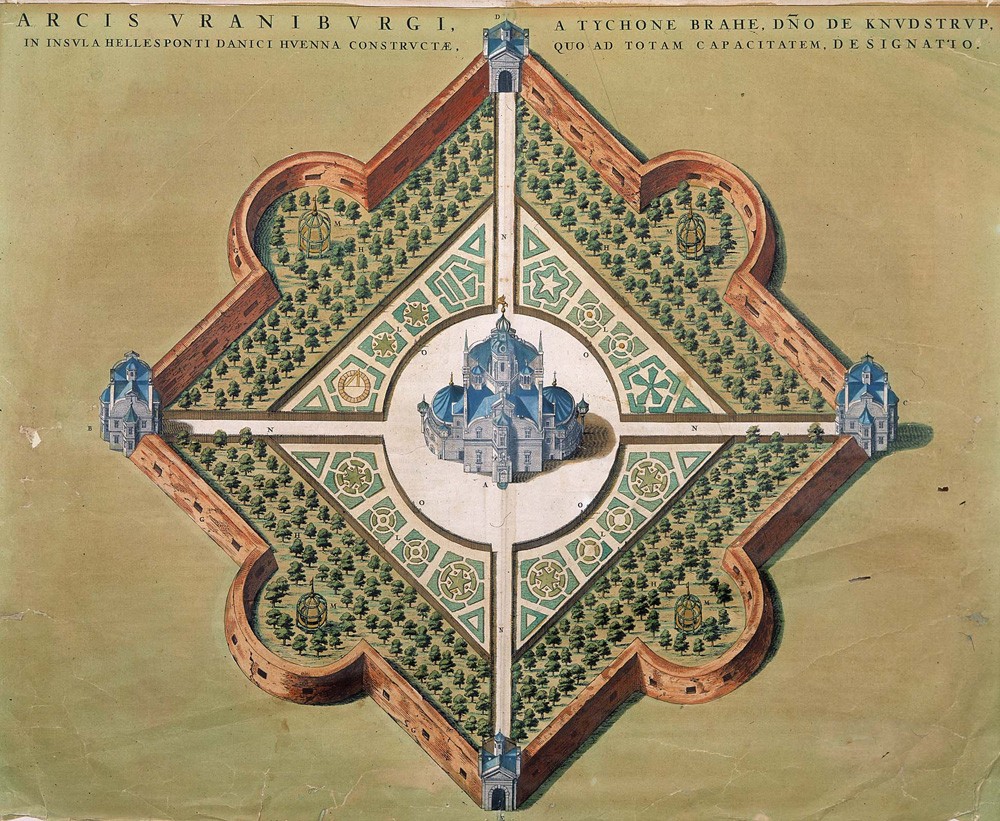

Fig. 1a. Uraniborg garden (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598) - Uraniborg observatory of Tycho Brahe (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1663)

Fig. 1b. Uraniborg garden (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598) - Uraniborg observatory of Tycho Brahe (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1663)

The brick building with sandstone and limestone frames was erected in 1576–1580 in the style of the Flemish Renaissance by the architect of the royal Danish court Hans van Steenwinckel der Ältere [Hans van Emden] (around 1545-1601) and the sculptor Johan Gregor van der Schardt (around 1530 - after 1581/91) in close cooperation with Tycho.

In the cellar was Tycho’s alchemical laboratory. The observatory measured 16m x 16m, with a 19m tower and two small round towers to the north and south of 6m diameter (with cone shaped roof), surrounded by galleries for the instruments.

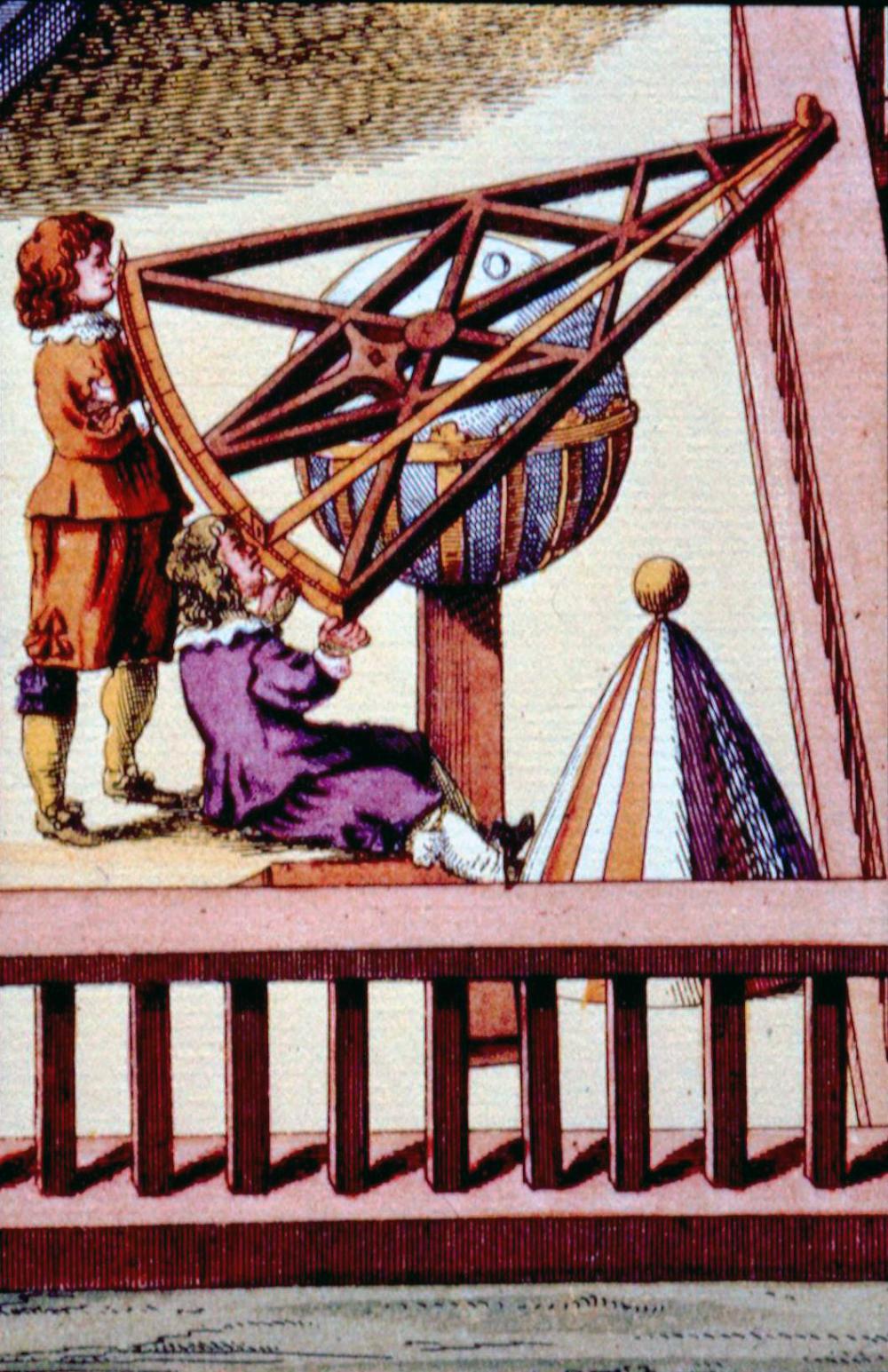

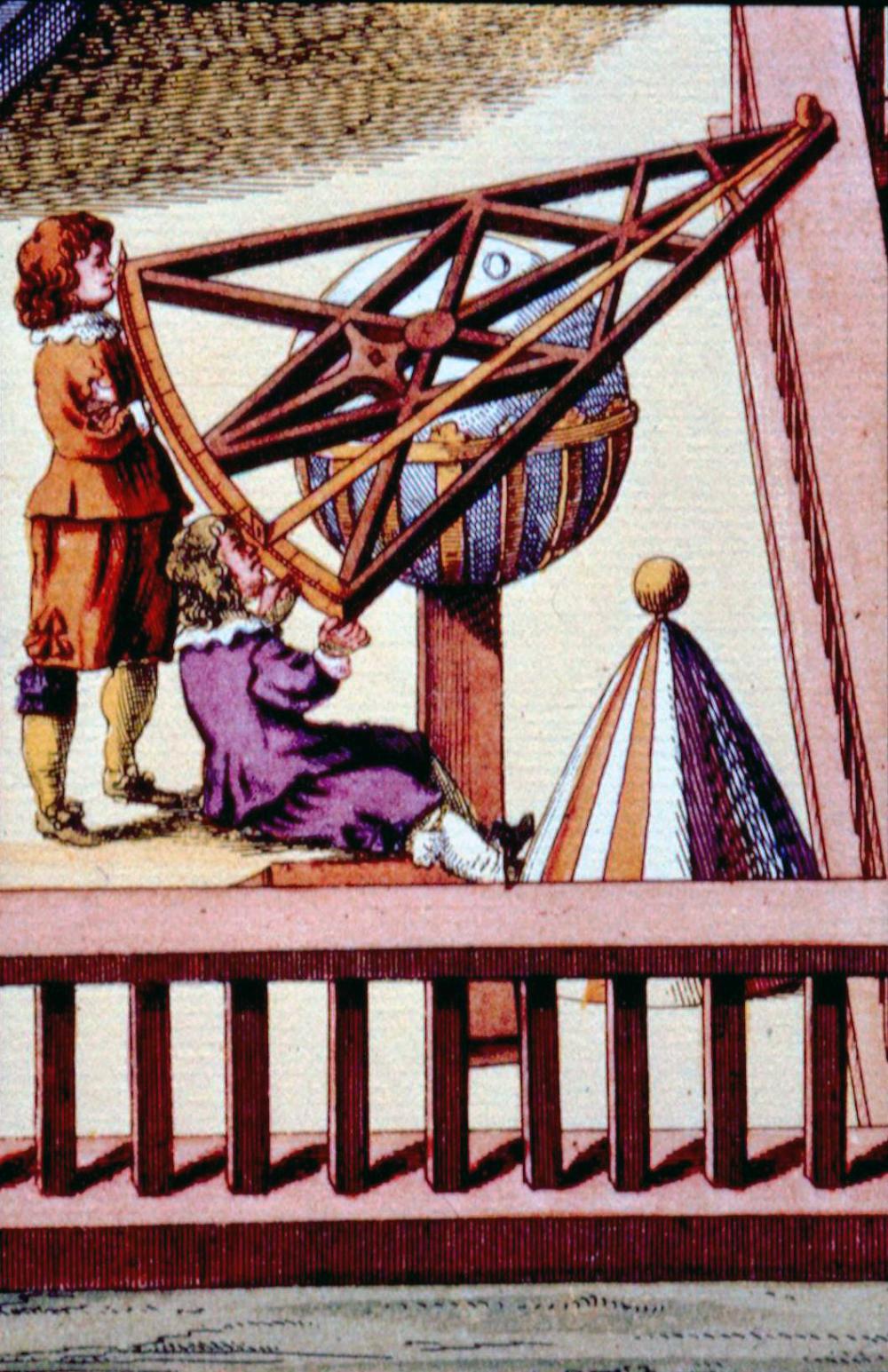

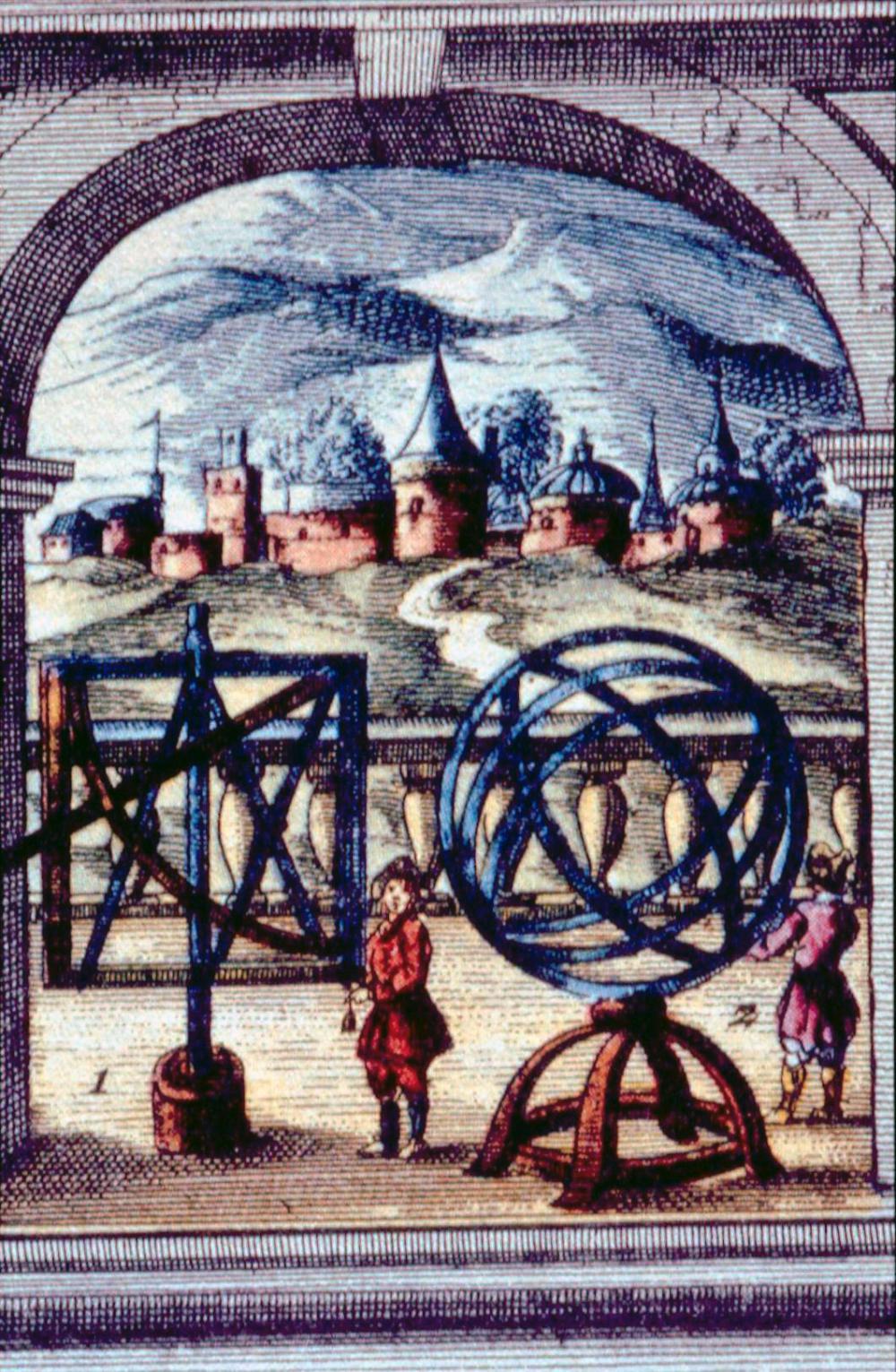

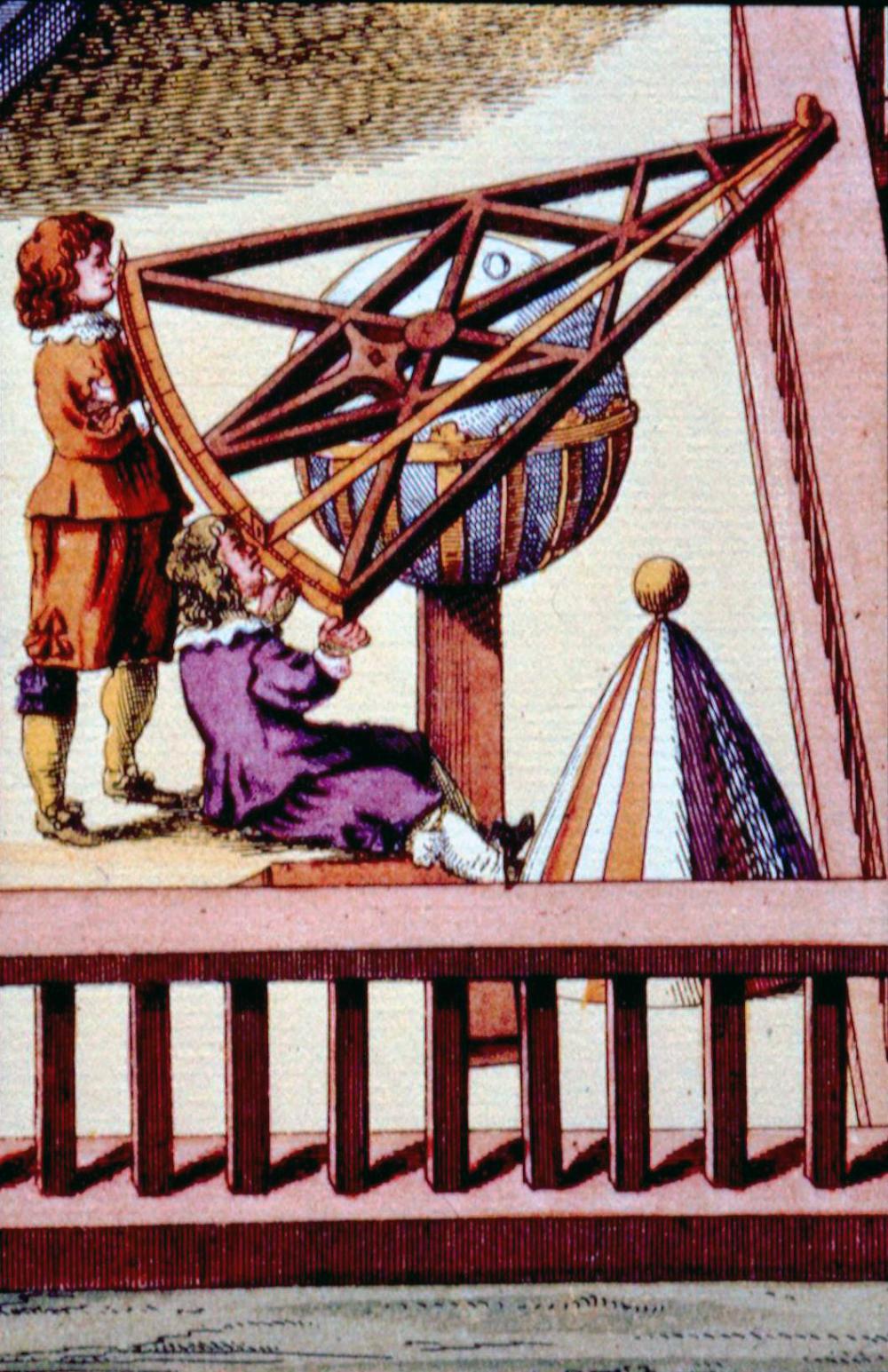

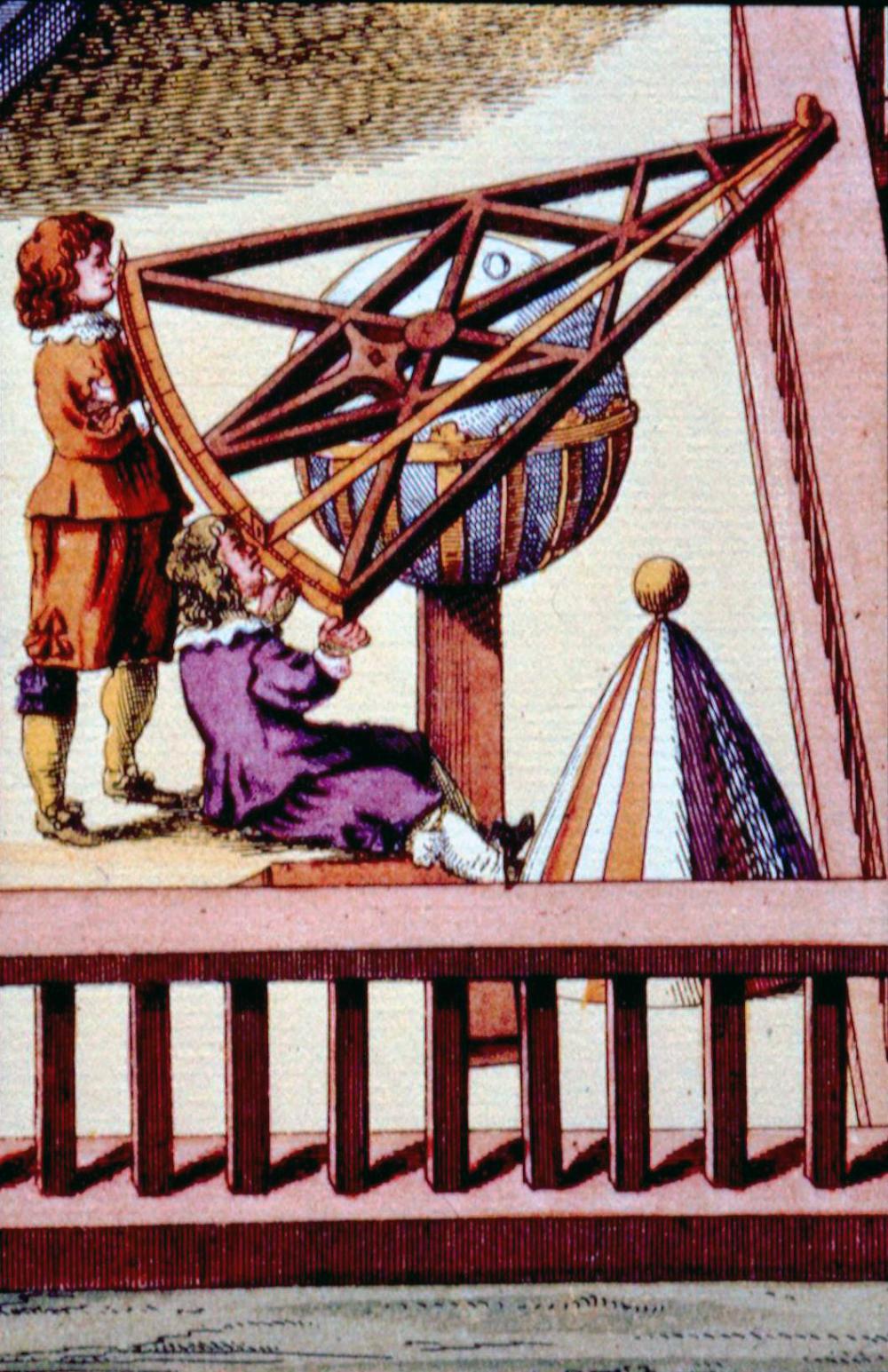

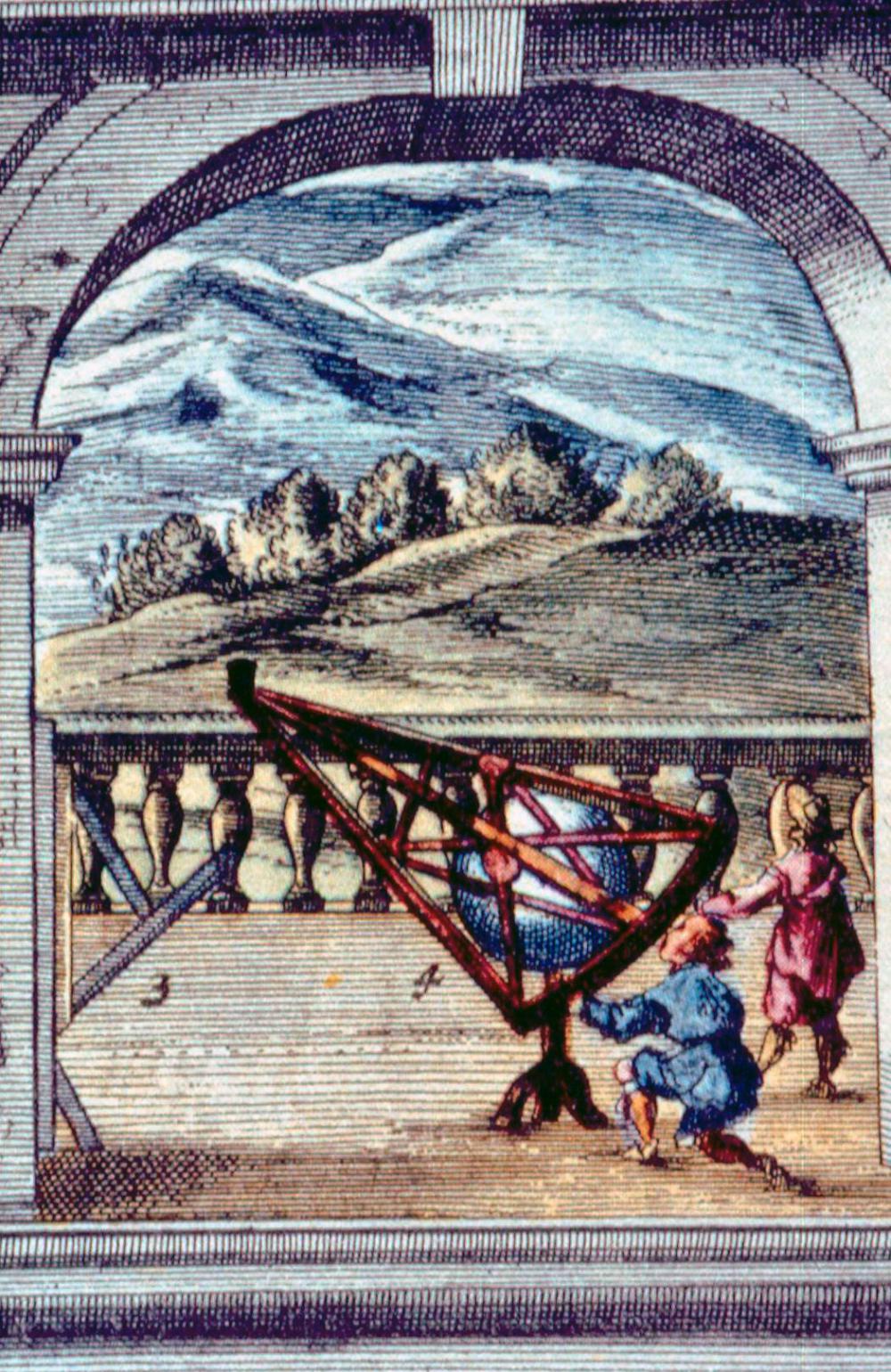

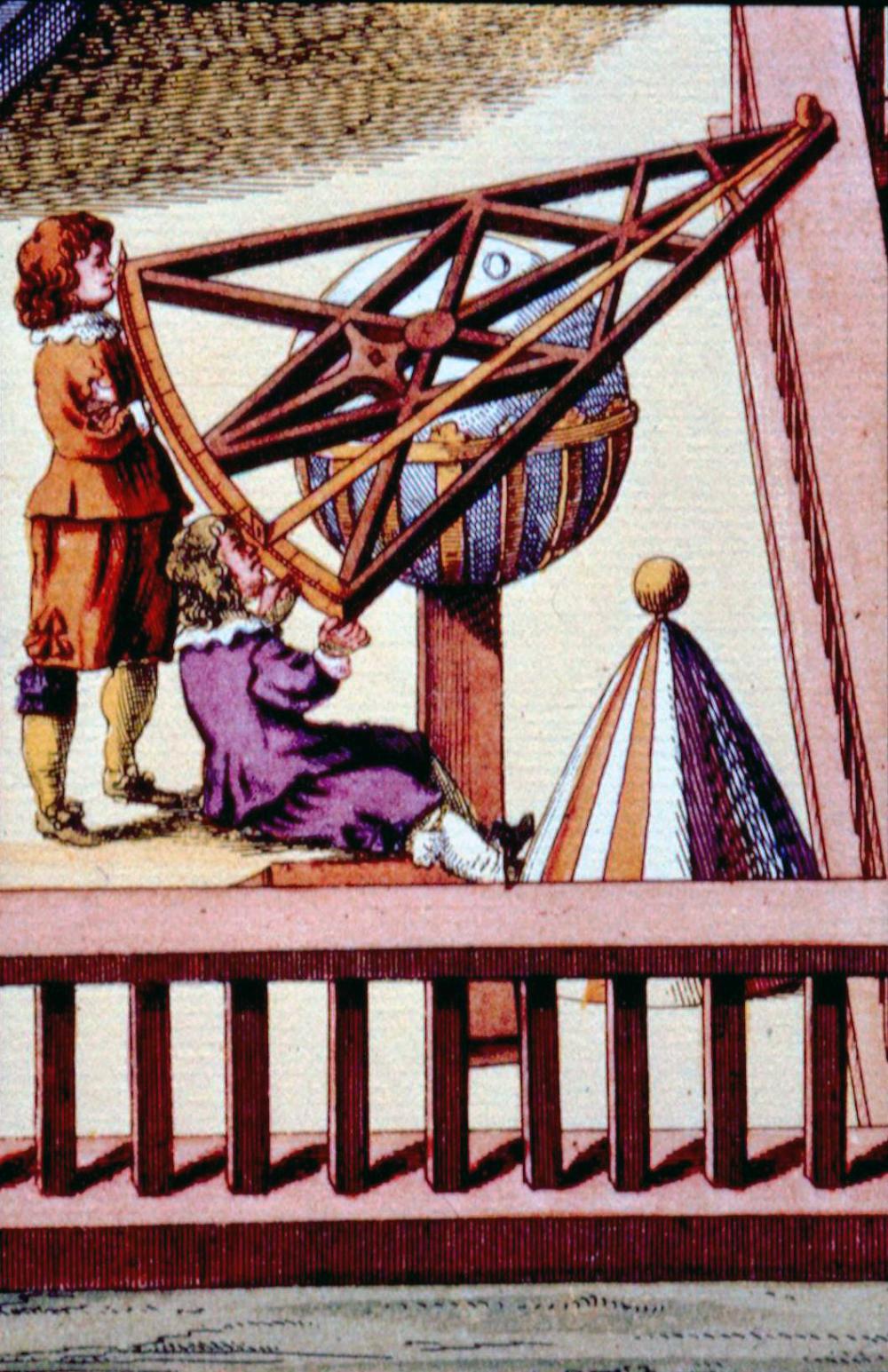

A large mural quadrant affixed to a north-south wall, which was used to measure the altitude of stars as they passed the meridian, was situated inside the observatory. The engraving of the mural quadrant from Brahe’s book Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (1598) shows very well the ongoing work in the observatory.

The observatory is in the middle of the strongly geometrical Renaissance garden; in addition Tycho had a printing office and a water mill for making paper.

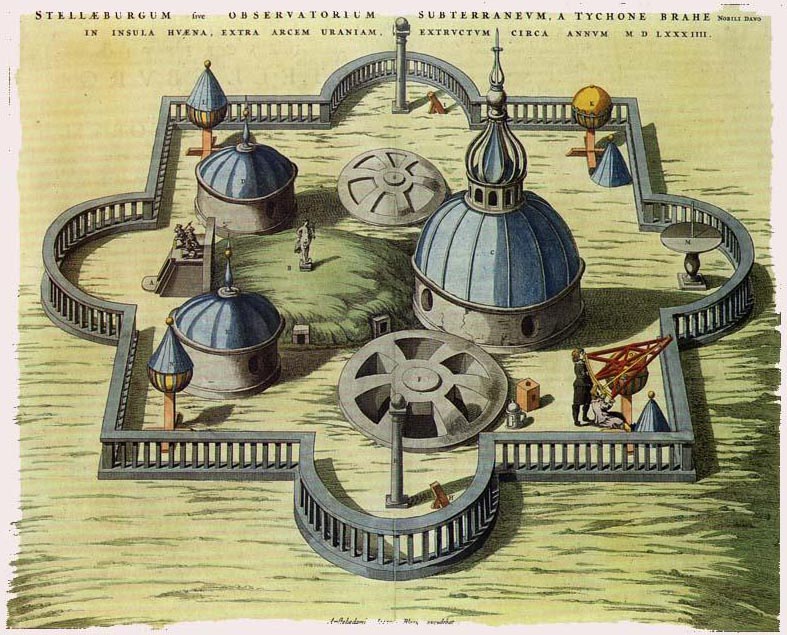

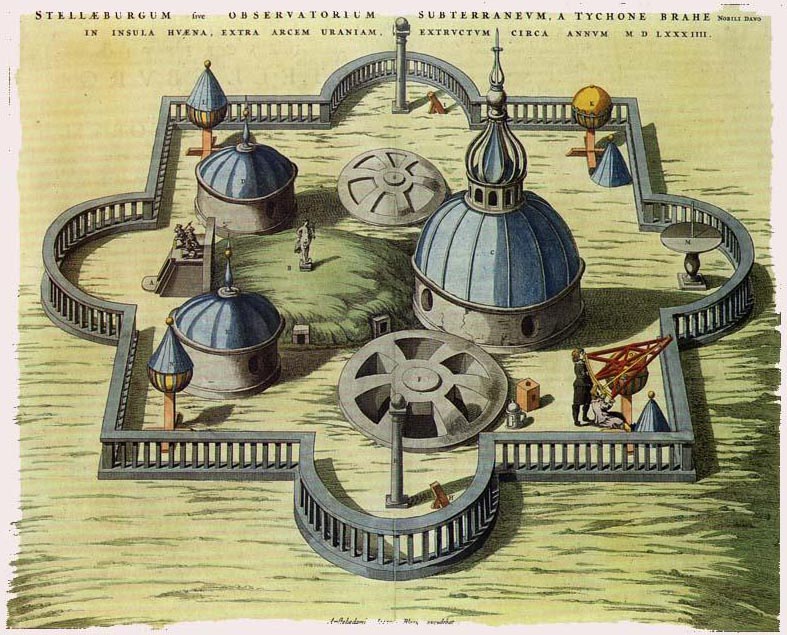

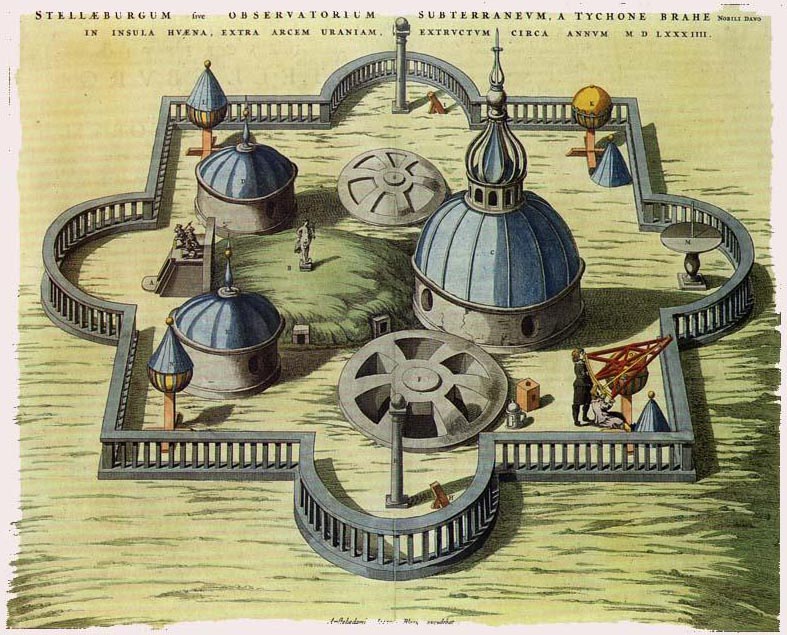

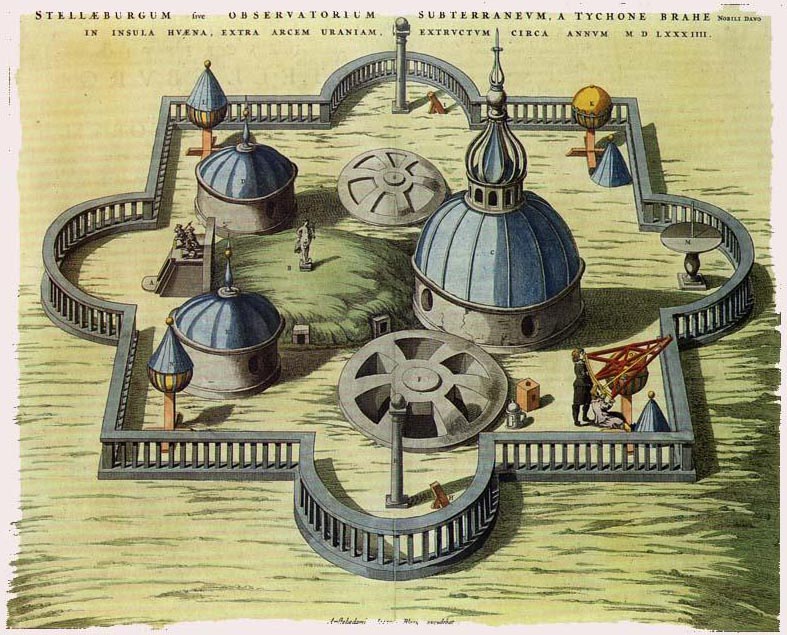

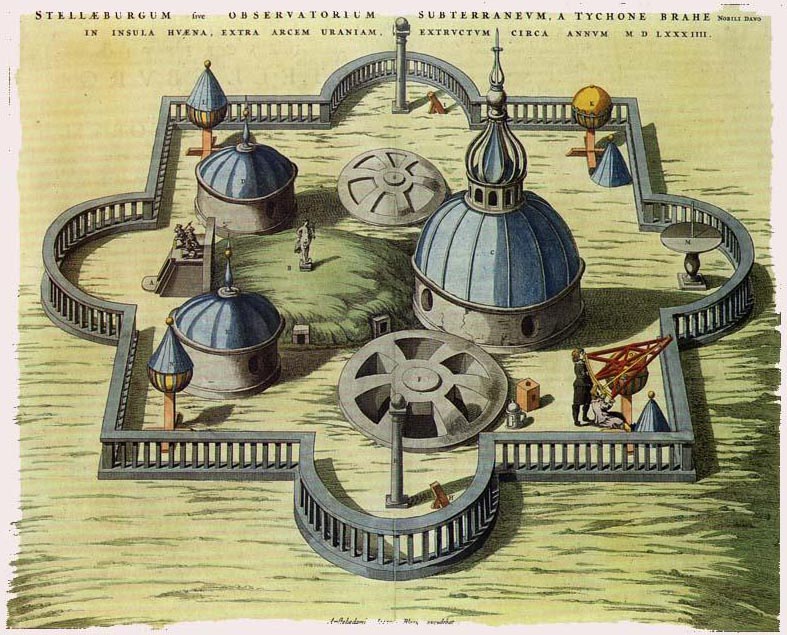

Fig. 2a. Tycho Brahe’s Stjerneborg, drawing by Willem Blaeu, circa 1595 (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1662, vol. 1)

Fig. 2b. Stjerneborg, today (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

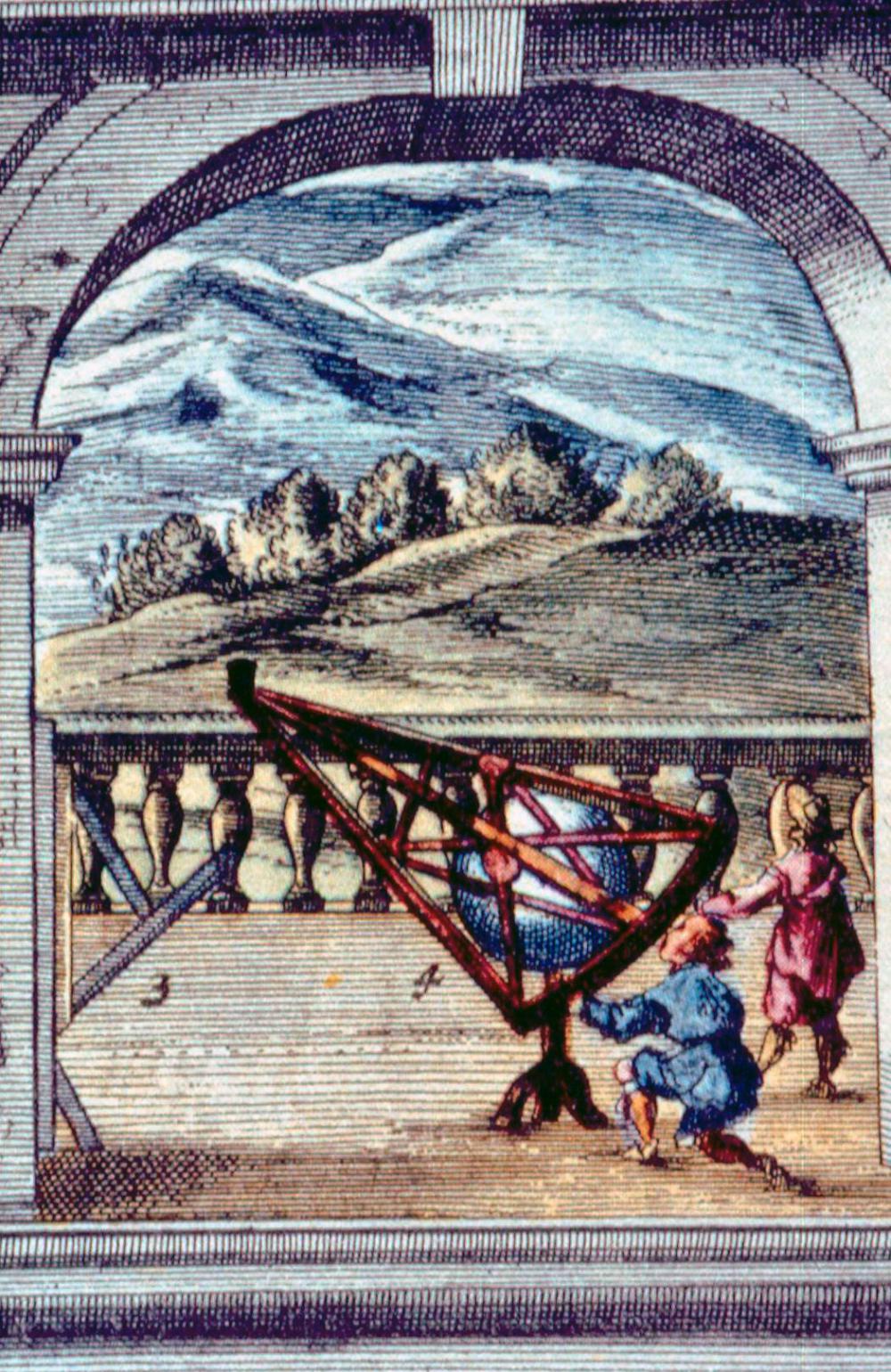

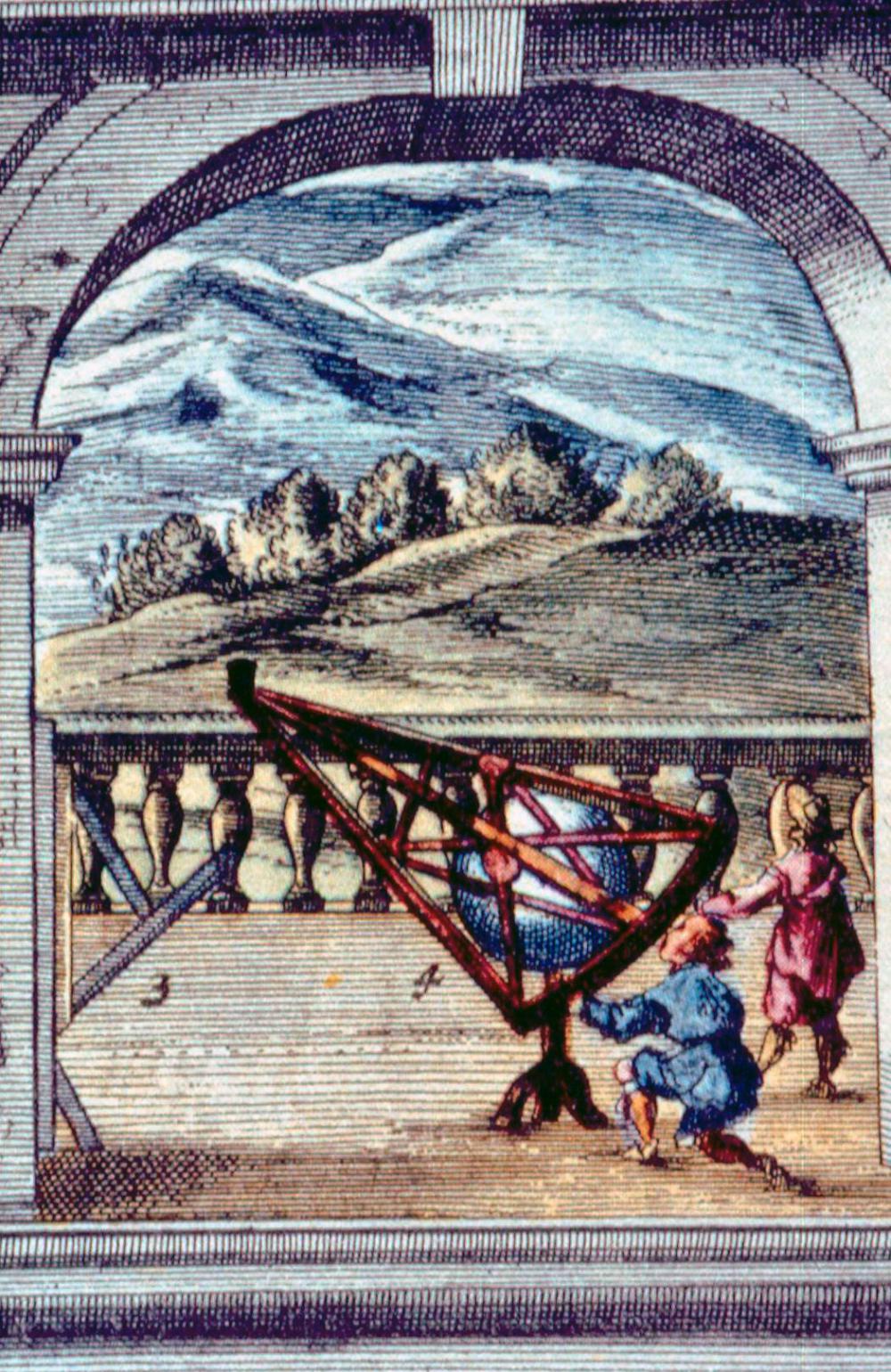

In 1584 Tycho founded a second observatory, Stellaeburgum (Stjerneborg), 80m to the south of Uraniborg. In its five round towers with conical domes, called "crypts" by Tycho, his instruments were well protected against the wind.

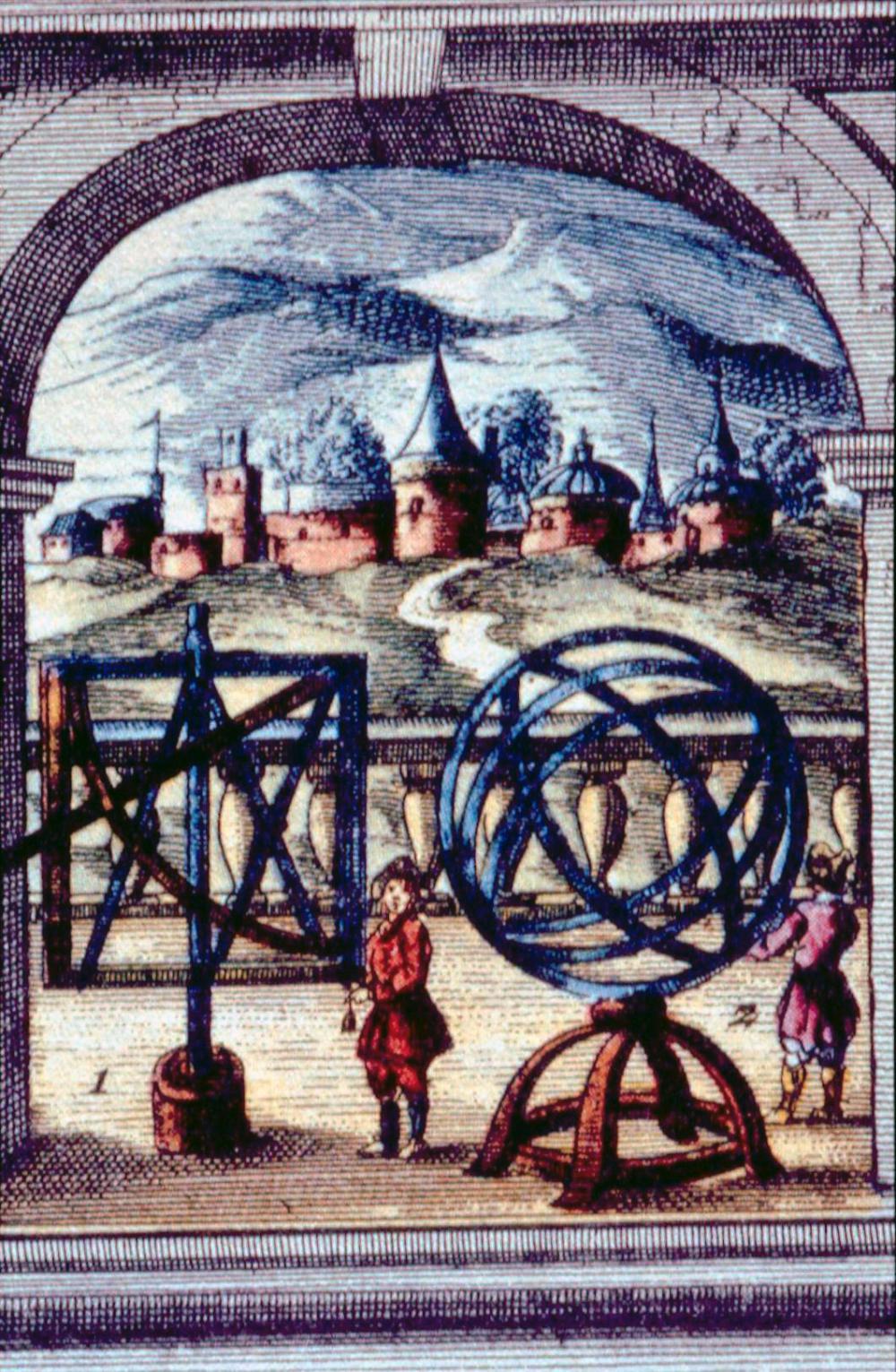

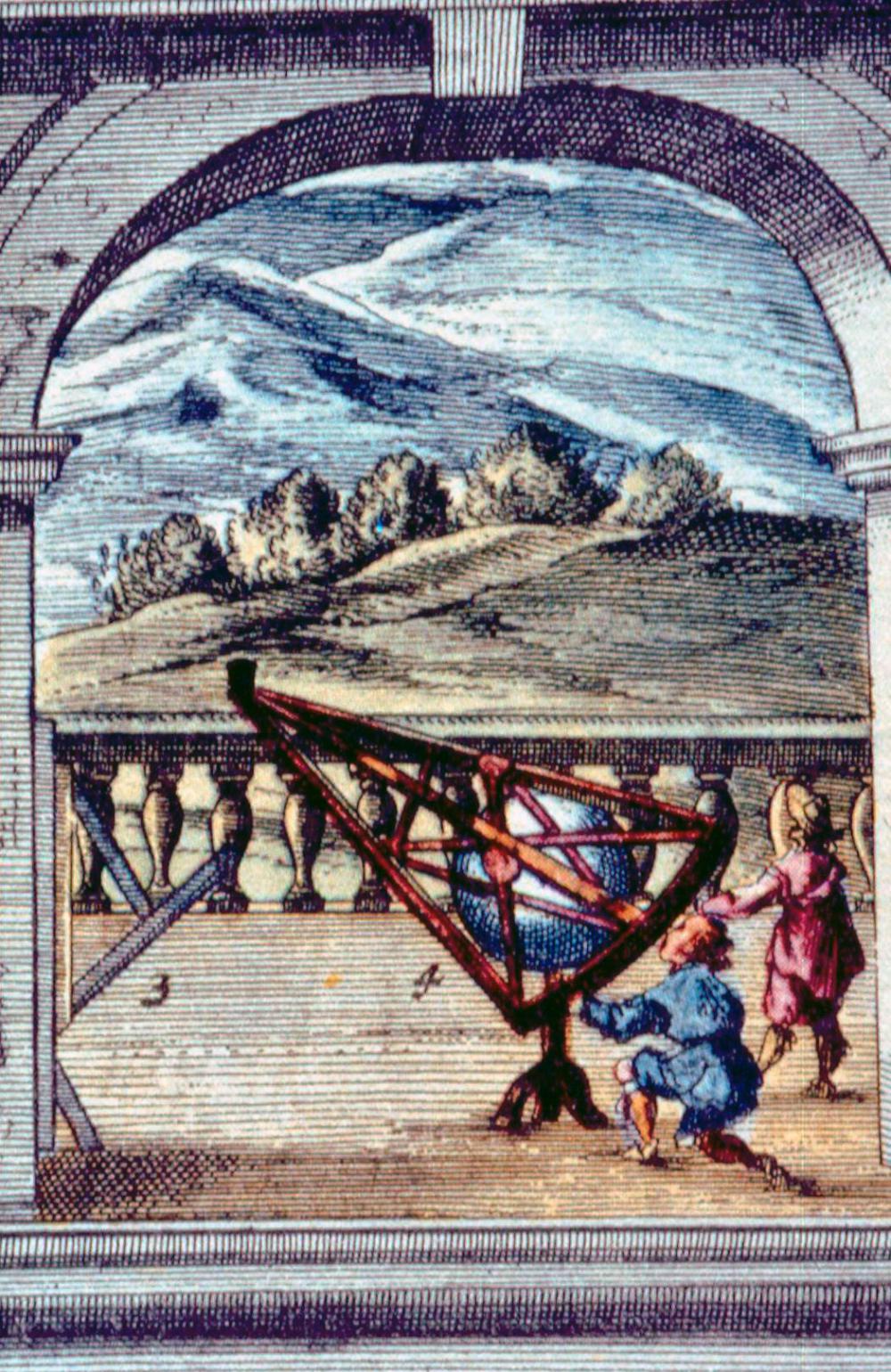

Very striking is the similarity of Tycho’s instruments - the triquetrum, armillary sphere, sextant and quadrant, as described in his Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandsbek, 1598) - to those used in Islamic observatories by al-’Urdī in Marâgha observatory, or by al-Âmilî in Isfāhān and by Taqī al-Dīn in Istanbul observatory.

Tycho’s castle observatory Uraniborg was, at the end of the 16th century, an impressive advanced research centre both for studying astronomy and in respect of the innovative precise instruments.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 15

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:28:50

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 3a. Portrait of Tycho Brahe (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) was the most important observational astronomer until the invention of the telescope in 1608. From his astronomical observations, Tycho Brahe recognised the need to design and construct improved instruments. The question is whether tradition or progress prevails here (Wolfschmidt 2010). On the one hand, Tycho relied on the three important ancient instruments - the Quadrant, Triquetrum and Armillary Sphere - and rejected recent medieval developments such as the Astrolab and Torquetum; on the other hand he recognised the shortcomings and innovatively improved many features of classical instruments.

Fig. 3b. Quadrant, replica in castle Benátek (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Particularly noteworthy is the creation of novel instruments (Large Mural Quadrant 1582, sextants, semicircles) and the development of new measurement and reduction methods. As part of his observations of the nova in 1572 and the comet in 1577, Tycho overrode the current Aristotelian ideas. On the other hand, he also interpreted the comet in a classical way (astrologically) as a negative omen. With his Tychonic world system, he tried to strike a balance between the ancient geocentric view of the world and the Copernican world system.

Instruments (Wolfschmidt 2002)

By constructing new instruments and devising new observing methods, Tycho succeeded in significantly increasing measurement accuracy. He increased the size of his instruments (e.g. a large wooden quadrant of diameter 5.4m and a mural quadrant); he used metal and masonry rather than wood; he modified construction techniques to achieve greater stability; to provide shelter from the wind, his instruments were in subterranean nooks; his instruments were permanently and solidly mounted; and, for better angular readings, he developed new subdivisions and diopters (Tycho used transversals to obtain the greatest possible angular resolution readings). His instrumental sights (diopters) were specially designed to minimise errors; he carefully analysed all the errors (Tycho’s aim was to reduce the uncertainty to less than one minute of an arc); he used fundamental stars for the first time; he preferred measuring equatorial coordinates directly instead of using the zodiacal system, i.e. using the equatorial armillary sphere instead of the zodiacal armillary sphere; he tried out a new measuring method with clocks and his mural quadrant (1582) for determining the right ascension; and he took atmospheric refraction into account.

Most of his high-accuracy instruments have been destroyed. Only two sextants, made by Jost Bürgi (1552-1632) and Erasmus Habermel (c. 1538-1606) around 1600, still exist in the Národní Technické Muzeum (NTM) [National Technical Museum] in Prague. A model of the wooden quadrant is in the round tower of the old observatory in Copenhagen.

But we have good descriptions of the instruments (half-circles of 2.3m radius; quadrants up to 2m radius including the mural quadrant; sextants up to 1.6m; armillary spheres of 1.5m radius and the great equatorial armillary sphere of 2.7m; triquetrum and celestial globe of 1.5m) in Tycho’s book Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandesburgi 1598, Nuremberg 1602).

One of Tycho’s instruments was reconstructed in its original measurements in Oldenburg University and in the Steno Museum in Aarhus, Denmark. In Munich, in the Deutsches Museum’s permanent astronomy exhibition (opened in 1992), the Uraniborg observatory and its instruments are shown at a scale of 1:10. A similar but larger model (scale 1:5) from the workshop of the Deutsches Museum was given to the Technical Museum in Malmø, Sweden. Tycho’s later observatory Stjerneborg can be seen as a reconstruction on the island Hven (Ven/Sweden) with the original foundations for the instruments.

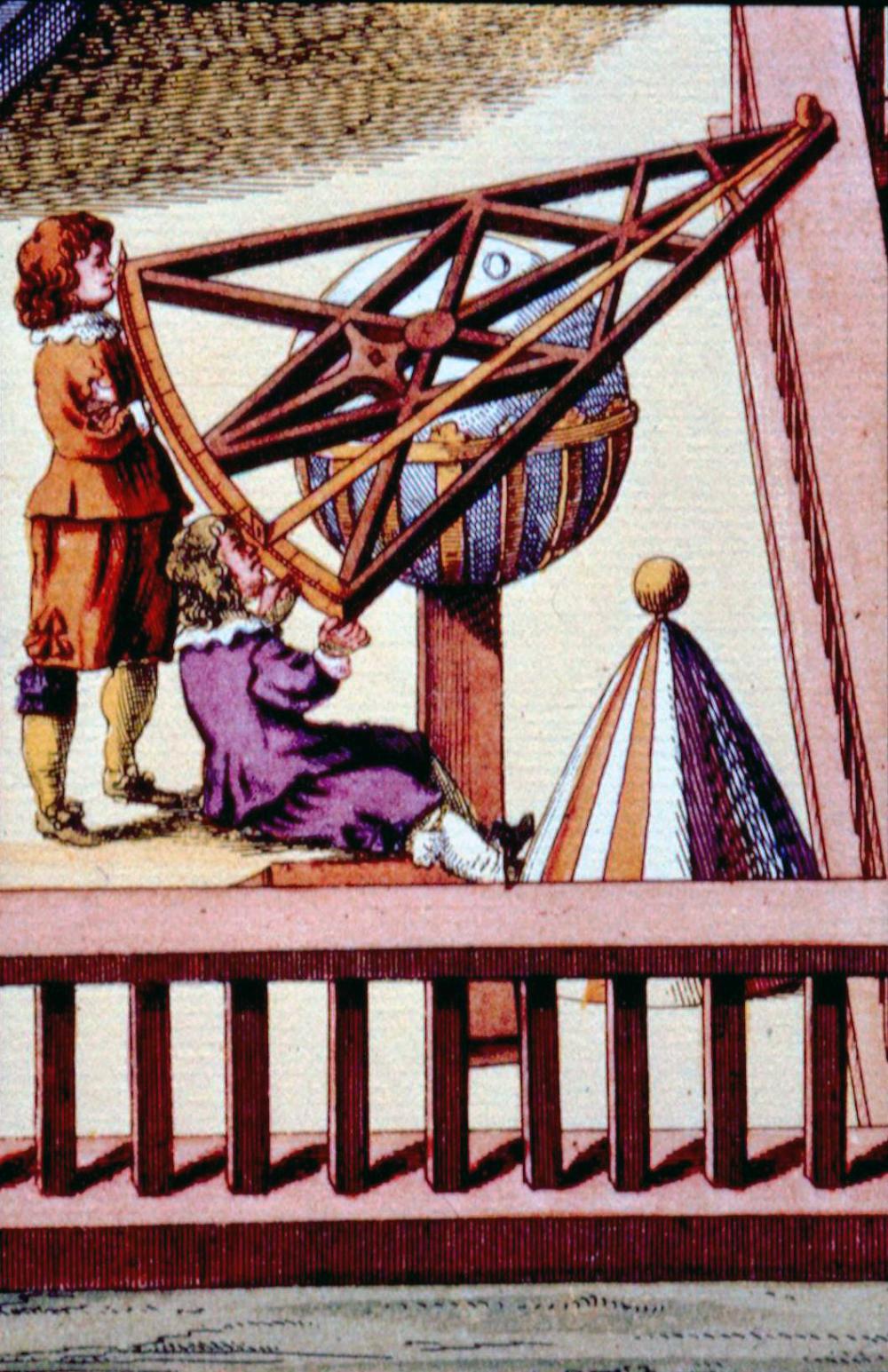

Fig. 4. Mural Quadrant, engraving of Tycho in his Uraniborg observatory (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 5a. Sextant, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 5b. observing with Sextant, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 5c. Armillary Sphere, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

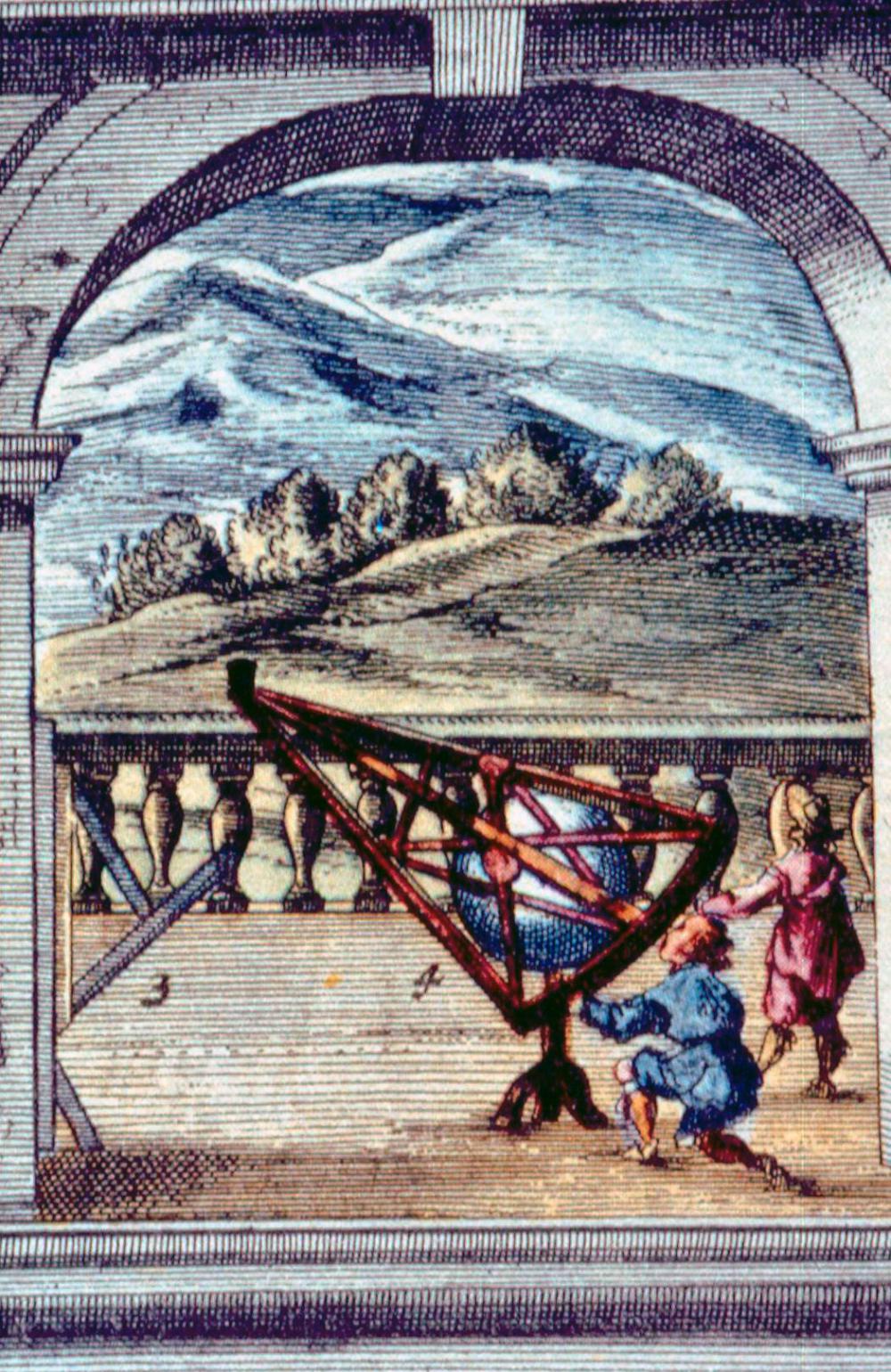

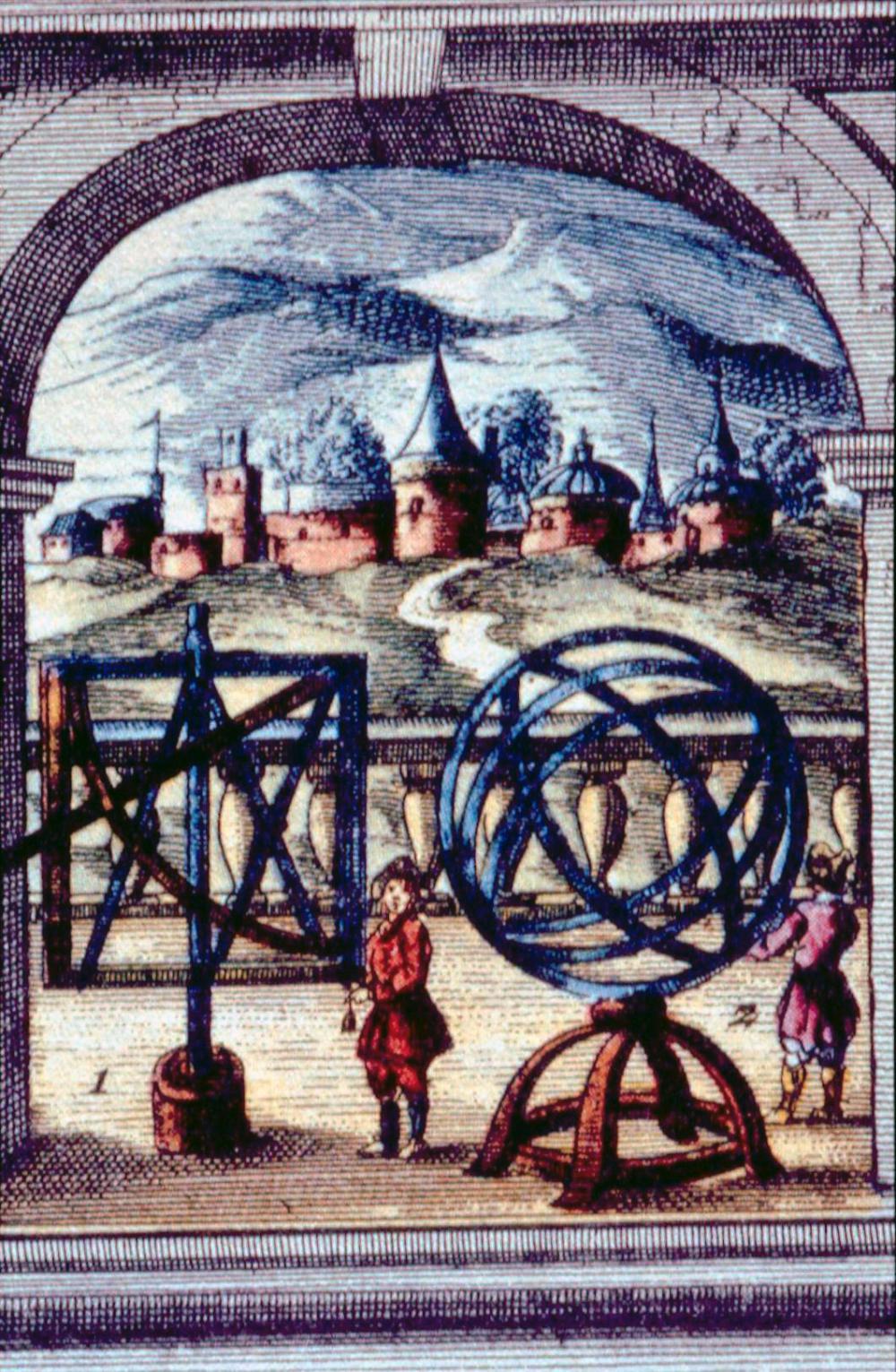

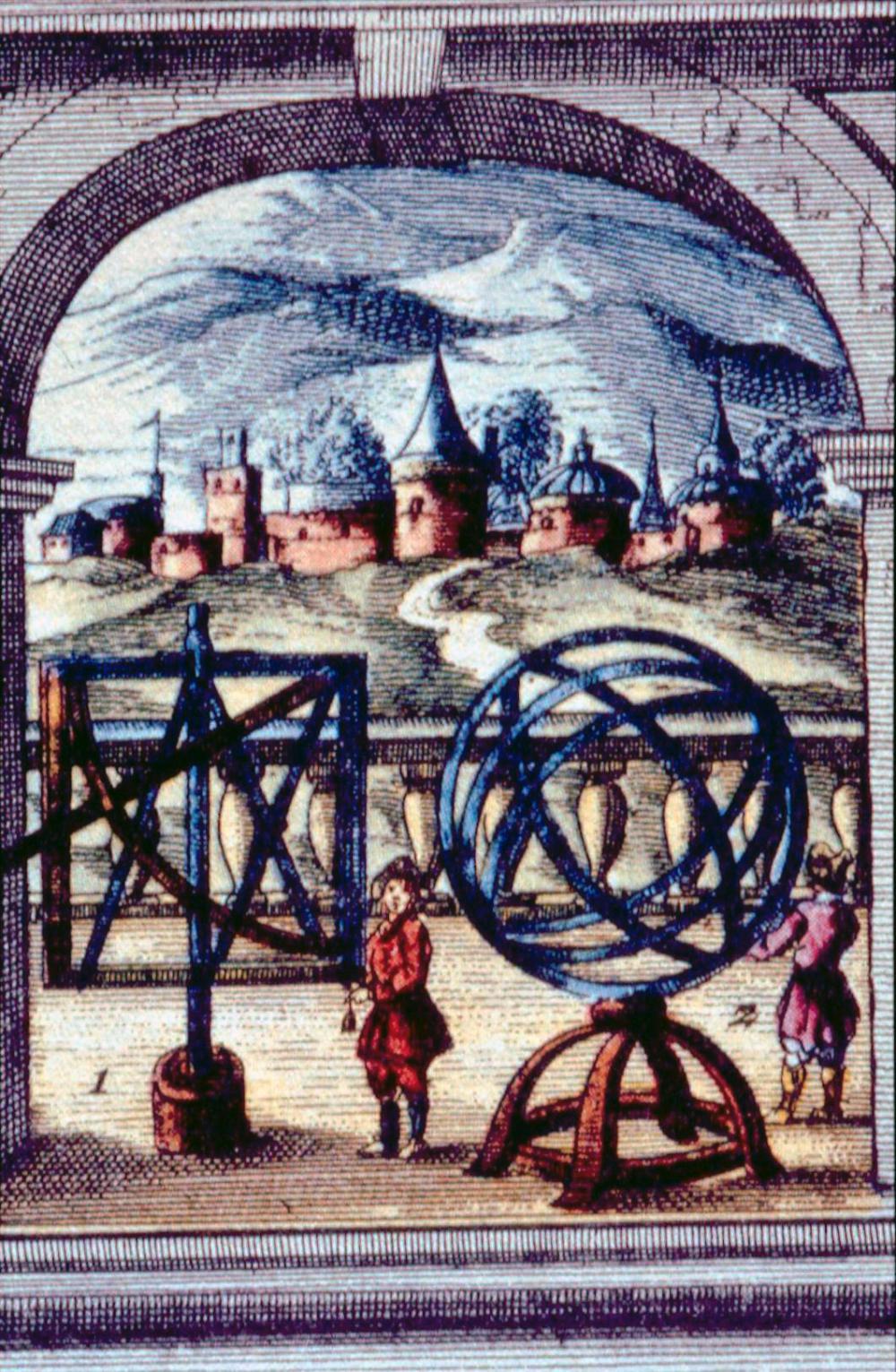

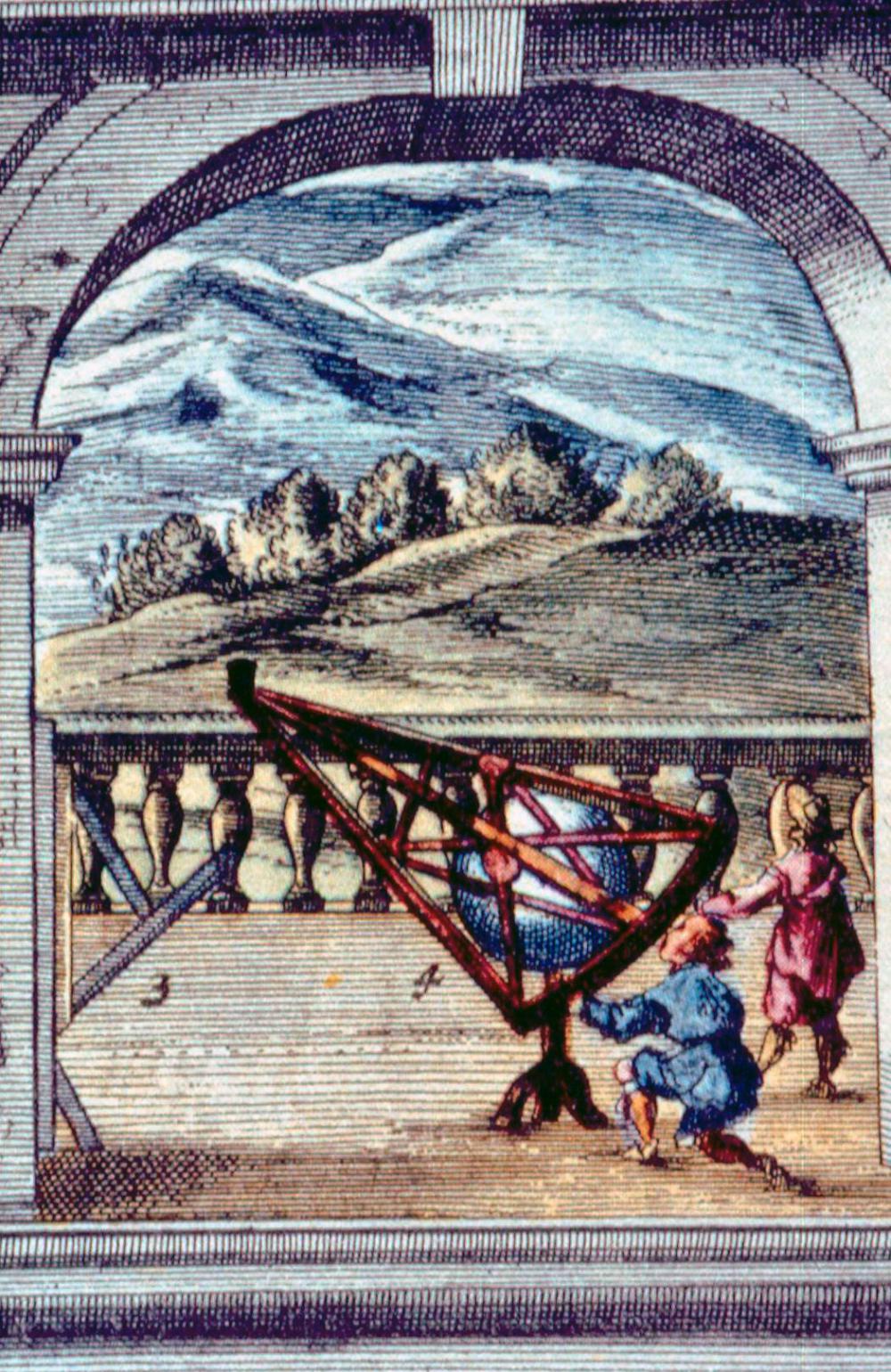

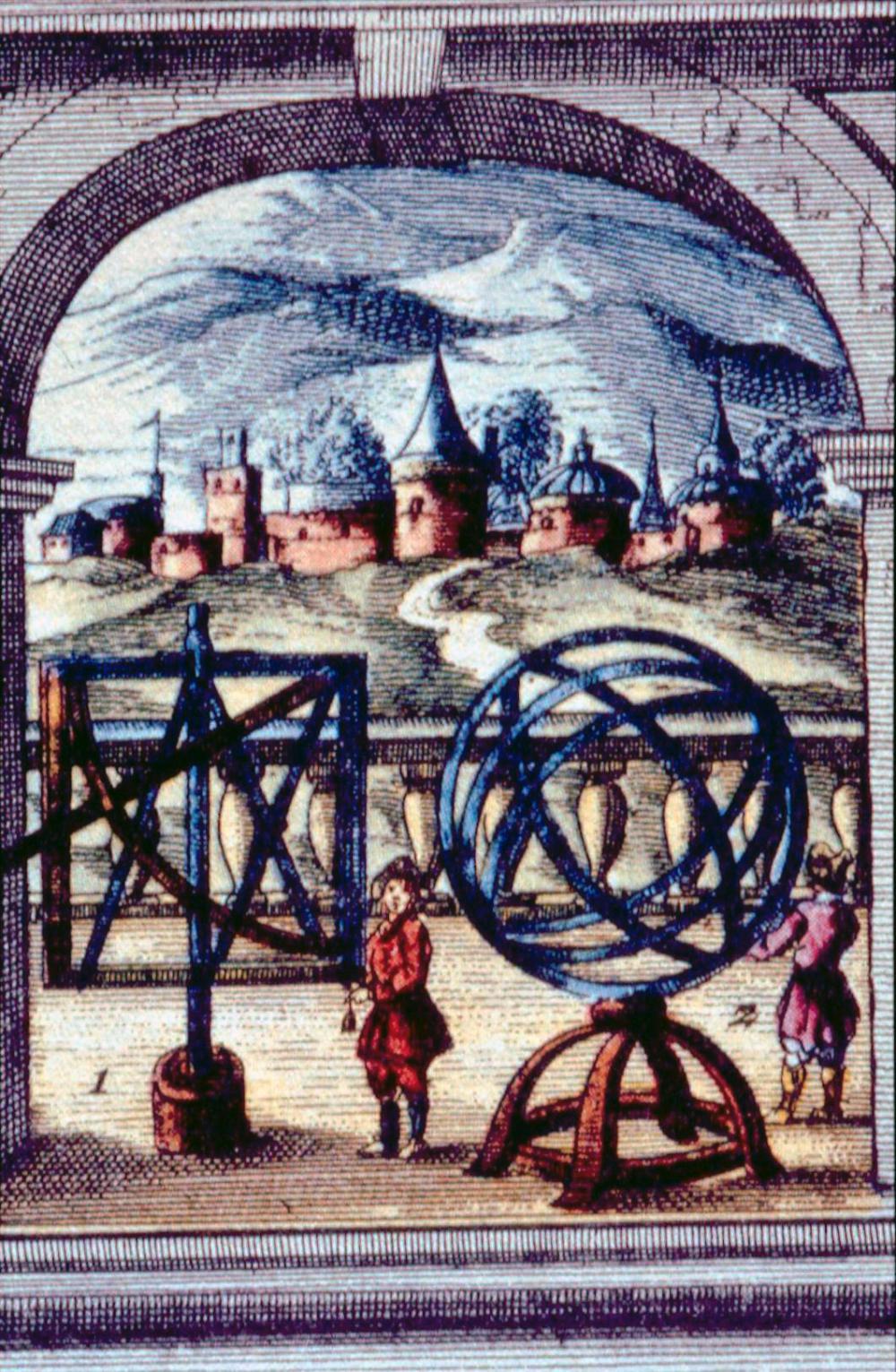

Fig. 6a. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6b. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6c. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6d. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 9

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 14:16:19

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 7a and 7b. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich (Photos: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Uraniborg no longer exists as an observatory (destroyed in 1601). But there is a very detailed description of the observatory and the instruments: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandsbek, 1598).

Fig. 8. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich with armillary sphere (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 9. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich with armillary spheres, sextant and triquetrum (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Some replicas were made: a scale model of Uraniborg with its instruments can be found in the Deutsches Museum Munich, and full-scale models of some instruments exist in other museums (Denmark, Sweden, Czech Republic).

Stellaeburgum was restored in the 1960s. The Renaissance garden around the observatory is reconstructed.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:48:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Renaissance building of Uraniborg (influenced by Palladio, cf. Roslund et al. 2007) was very impressive, large and new - nothing similar to this observatory had existed before. The architecture of Uraniborg (Wolfschmidt 2010) may have been modelled on the symmetrical layout of Chambord Castle on the Loire (1539) or the buildings of the Italian Renaissance architects Andrea Palladio (1508-1580), or Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554) - particularly the Villa Rotonda (1552) in Vicenza near Venice.

A comparative study (İhsanoğlu 2004) shows the strong influence of Islamic instruments such as those of Maragha and Samarkand observatories, and that of Taqi al-Din used in Istanbul observatory, on Tycho’s. But the architecture of the observatory and the mounting was different.

The Round Tower in Copenhagen was inaugurated in 1642 as a replacement for Uraniborg’s astronomical functions.

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-09-05 19:49:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Tycho Brahe-Museet, Landsvägen 182 Ven

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 16:01:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Archenhold, Friedrich Simon & M. Albrecht: Ausgrabungen und Vermessungen der Sternwartenreste Tycho Brahes auf der Insel Hven. In: Das Weltall, Vorträge und Abhandlungen, Heft 9 (1902). Treptow bei Berlin, p. 1-20

- Arrest, Heinrich Louis d’: Die Ruinen von Uranienborg und Stjerneborg im Sommer 1868. In: Astronomische Nachrichten 72 (1868), Nr. 1718, p. 209-224.

Here you find the important information: 1 tychonic cubit = 39 cm, 1 tychonic foot = 25,9 cm - Beckett, Francis & Charles Christensen: Tycho Brahe’s Uraniborg und Stjerneborg on the Island of Hveen. London, Copenhagen 1921, p. 35-43, Abb. 1-9

- Blaeu, Willem Janszoon & Johann: Le theatre du monde ou nouvel Atlas (Theatrum orbis terrarum). 1635

- Blaeu, Johann: Geographia Blaviana Atlas Major. 11 vol. Amsterdam 1662

- Blaeu, Johann: Le Grand Atlas. 12 vol. Amsterdam 1663

- Brahe, Tycho: De mundi aetherei. Uraniborg 1588

- Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica. Wandsbek 1598

- Chapman, Allan: Astronomical Instruments and Their Users. Tycho Brahe to William Lassell. England (Collected Studies 530). Aldershot 1996

- Christianson, John Robert: Tycho Brahe. In: Carsten Bach-Nielsen (Red.): Danmark og renæssancen. 1500-1650. Copenhagen: Gad 2006

- Dreyer, John Louis Emil: Tycho Brahe. A Picture of Scientific Life and Work in the Sixteenth Century. Edinburgh 1890. New York, London: Dover 1963. Deutsche Übersetzung von M. Bruhns: Tycho Brahe. Ein Bild wissenschaftlichen Lebens und Arbeitens im sechzehnten Jahrhundert. Mit einem Vorwort von Wilhelm Valentiner. Karlsruhe 1894 (Reprint Vaduz/Lichtenstein 1992)

- Dreyer, John Louis Emil: Tychonis Brahe Dani Opera Omnia. Hg. von John Louis Emil Dreyer. 15 Vol. Kopenhagen 1913-1928

- İhsanoğlu, E.: The Introduction of Western Science to the Ottoman World: A Case Study of Modern Astronomy (1660-1860). In: Science, technology and learning in the Ottoman Empire: Western influence, local institutions, and the transfer of knowledge. Ed. by İhsanoğlu, E.; Aldershot, Hants, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company (Variorum Collected Studies) 2004

- Kwan, Alistair: Tycho’s Talisman: Astrological Magic in the Design of Uraniborg. In: Early Science and Medicine 16 (2011), p. 95-119

- Raeder, Hans; Strömgren, Elis & Bengt Strömgren: Tycho Brahe’s Description of his Instruments and Scientific Work as given in Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica. Wandesburgi (Wandsbek near Hamburg) 1598. Copenhagen 1946

- Rankl, Richard: Der Tychonische Sextant (von Bürgi) in der Sternwarte Kremsmünster. In: 89. Jahresbericht des Obergymnasiums der Benediktiner zu Kremsmünster. Linz 1946, p. 3-15

- Roslund, C.; Pásztor, Emília & G. Olofsson: Tycho Brahe’s Uraniborg: An Italian High Renaissance Villa. In: Papers from the annual meeting of SEAC (European Society for Astronomy in Culture) held in Kecskemét in Hungary in 2004. Ed. by Emília Pásztor. Oxford: Hadrian Books (BAR International Series 1647) 2007

- Šima, Zdislav: Prague Sextants of Tycho Brahe. In: Annals of Science 50 (1993), S. 445-453; vgl. Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society 35 (1992), p. 7-10

- Thoren, Victor E.: New Light on Tycho’s Instruments. In: Journal for the History of Astronomy 9 (1973), p. 25-45

- Wesley, Walter G.: The Accuracy of Tycho Brahe’s Instruments. In: Journal for the History of Astronomy 9 (1978), p. 42-53

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: All-Wissen - Tycho Brahes Sternwarte Uraniborg. In: Kultur und Technik 20 (1996), Heft 4, p. 12-13

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) - the Best Observing Astronomer in 16th Century. In: Schielicke, Reinhard E. (Hg.): Astronomische Gesellschaft - Abstract Series No. 12 (1996). Hamburg 1996, p. 123

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Tycho Brahe - Instrumentenbauer und Meister der Beobachtungstechnik. In: Florilegium Astronomicum. Festschrift für Felix Schmeidler. Hrsg. von Menso Folkerts, Stefan Kirschner, Theodor Schmidt-Kaler. München: Institut für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften (Algorismus, Heft 37) 2001, p. 293-323

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: The Observatories and Instruments of Tycho Brahe. In: Tycho Brahe and Prague: Crossroads of European Science. Proceedings of the International Symposium on the History of Science in the Rudolphine Period; Prague, 22-25 October 2001. Hrsg. von Christianson, John Robert; Hadravová, Alena; Hadrava, Petr and Martin Šolc. Frankfurt am Main: Harri Deutsch (Acta Historica Astronomiae Vol. 16) 2002, p. 203-216

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun & Martin Šolc: ,,Astronomy in and around Prague’’. Proceedings of the Colloquium of the Working Group for the History of Astronomy, Sept. 20, 2004, organized by Gudrun Wolfschmidt and Martin Šolc. Acta Universitatis Carolinae - Mathematica et Physica, Vol. 46, Supplementum (2005)

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Tycho Brahes Instrumente - historische Wurzeln, Innovation und Nachwirkung. In: Innovation durch Wissenstransfer in der Frühen Neuzeit. Kultur- und geistesgeschichtliche Studien zu Austauschprozessen in Mitteleuropa. Hg. von Johann Anselm Steiger, Sandra Richter und Marc Föcking. Amsterdam, New York: Rodopi B.V. (CHLOE Beihefte zum Daphnis; vol. 41) 2010, p. 249-278

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-09-05 19:50:51

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Tycho Brahe-Museet, Landsvägen 182 Ven

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:20:02

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Tycho’s observatories, Uraniborg and Stellaeburgum (Stjerneborg), on the Danish Island of Hven in the Øresund between Zealand and Scania (today Ven, Swedish).

Location - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-19 10:02:00

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Uraniborg 55° 54′ 28.3″ N, 12° 41′ 47.7″ E, elevation 44m above mean sea level.

Stjärneborg 55° 54′ 24.7″ N, 12° 41′ 49.3″ E, elevation 42m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 13:26:30

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

---

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 19

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:24:29

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Under the sponsorship of King Frederic II of Denmark (1534–1588), Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) built his observatory, called "Uraniborg", dedicated to Urania, the Muse of Astronomy (Wolfschmidt 2002a) on the Danish Island of Hven (today Ven, Swedish). It was the first time that a building was erected in Europe especially for the purpose of astronomical observations.

Fig. 1a. Uraniborg garden (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598) - Uraniborg observatory of Tycho Brahe (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1663)

Fig. 1b. Uraniborg garden (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598) - Uraniborg observatory of Tycho Brahe (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1663)

The brick building with sandstone and limestone frames was erected in 1576–1580 in the style of the Flemish Renaissance by the architect of the royal Danish court Hans van Steenwinckel der Ältere [Hans van Emden] (around 1545-1601) and the sculptor Johan Gregor van der Schardt (around 1530 - after 1581/91) in close cooperation with Tycho.

In the cellar was Tycho’s alchemical laboratory. The observatory measured 16m x 16m, with a 19m tower and two small round towers to the north and south of 6m diameter (with cone shaped roof), surrounded by galleries for the instruments.

A large mural quadrant affixed to a north-south wall, which was used to measure the altitude of stars as they passed the meridian, was situated inside the observatory. The engraving of the mural quadrant from Brahe’s book Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (1598) shows very well the ongoing work in the observatory.

The observatory is in the middle of the strongly geometrical Renaissance garden; in addition Tycho had a printing office and a water mill for making paper.

Fig. 2a. Tycho Brahe’s Stjerneborg, drawing by Willem Blaeu, circa 1595 (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1662, vol. 1)

Fig. 2b. Stjerneborg, today (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

In 1584 Tycho founded a second observatory, Stellaeburgum (Stjerneborg), 80m to the south of Uraniborg. In its five round towers with conical domes, called "crypts" by Tycho, his instruments were well protected against the wind.

Very striking is the similarity of Tycho’s instruments - the triquetrum, armillary sphere, sextant and quadrant, as described in his Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandsbek, 1598) - to those used in Islamic observatories by al-’Urdī in Marâgha observatory, or by al-Âmilî in Isfāhān and by Taqī al-Dīn in Istanbul observatory.

Tycho’s castle observatory Uraniborg was, at the end of the 16th century, an impressive advanced research centre both for studying astronomy and in respect of the innovative precise instruments.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 15

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:28:50

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 3a. Portrait of Tycho Brahe (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) was the most important observational astronomer until the invention of the telescope in 1608. From his astronomical observations, Tycho Brahe recognised the need to design and construct improved instruments. The question is whether tradition or progress prevails here (Wolfschmidt 2010). On the one hand, Tycho relied on the three important ancient instruments - the Quadrant, Triquetrum and Armillary Sphere - and rejected recent medieval developments such as the Astrolab and Torquetum; on the other hand he recognised the shortcomings and innovatively improved many features of classical instruments.

Fig. 3b. Quadrant, replica in castle Benátek (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Particularly noteworthy is the creation of novel instruments (Large Mural Quadrant 1582, sextants, semicircles) and the development of new measurement and reduction methods. As part of his observations of the nova in 1572 and the comet in 1577, Tycho overrode the current Aristotelian ideas. On the other hand, he also interpreted the comet in a classical way (astrologically) as a negative omen. With his Tychonic world system, he tried to strike a balance between the ancient geocentric view of the world and the Copernican world system.

Instruments (Wolfschmidt 2002)

By constructing new instruments and devising new observing methods, Tycho succeeded in significantly increasing measurement accuracy. He increased the size of his instruments (e.g. a large wooden quadrant of diameter 5.4m and a mural quadrant); he used metal and masonry rather than wood; he modified construction techniques to achieve greater stability; to provide shelter from the wind, his instruments were in subterranean nooks; his instruments were permanently and solidly mounted; and, for better angular readings, he developed new subdivisions and diopters (Tycho used transversals to obtain the greatest possible angular resolution readings). His instrumental sights (diopters) were specially designed to minimise errors; he carefully analysed all the errors (Tycho’s aim was to reduce the uncertainty to less than one minute of an arc); he used fundamental stars for the first time; he preferred measuring equatorial coordinates directly instead of using the zodiacal system, i.e. using the equatorial armillary sphere instead of the zodiacal armillary sphere; he tried out a new measuring method with clocks and his mural quadrant (1582) for determining the right ascension; and he took atmospheric refraction into account.

Most of his high-accuracy instruments have been destroyed. Only two sextants, made by Jost Bürgi (1552-1632) and Erasmus Habermel (c. 1538-1606) around 1600, still exist in the Národní Technické Muzeum (NTM) [National Technical Museum] in Prague. A model of the wooden quadrant is in the round tower of the old observatory in Copenhagen.

But we have good descriptions of the instruments (half-circles of 2.3m radius; quadrants up to 2m radius including the mural quadrant; sextants up to 1.6m; armillary spheres of 1.5m radius and the great equatorial armillary sphere of 2.7m; triquetrum and celestial globe of 1.5m) in Tycho’s book Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandesburgi 1598, Nuremberg 1602).

One of Tycho’s instruments was reconstructed in its original measurements in Oldenburg University and in the Steno Museum in Aarhus, Denmark. In Munich, in the Deutsches Museum’s permanent astronomy exhibition (opened in 1992), the Uraniborg observatory and its instruments are shown at a scale of 1:10. A similar but larger model (scale 1:5) from the workshop of the Deutsches Museum was given to the Technical Museum in Malmø, Sweden. Tycho’s later observatory Stjerneborg can be seen as a reconstruction on the island Hven (Ven/Sweden) with the original foundations for the instruments.

Fig. 4. Mural Quadrant, engraving of Tycho in his Uraniborg observatory (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 5a. Sextant, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 5b. observing with Sextant, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 5c. Armillary Sphere, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 6a. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6b. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6c. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6d. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 9

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 14:16:19

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 7a and 7b. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich (Photos: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Uraniborg no longer exists as an observatory (destroyed in 1601). But there is a very detailed description of the observatory and the instruments: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandsbek, 1598).

Fig. 8. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich with armillary sphere (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 9. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich with armillary spheres, sextant and triquetrum (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Some replicas were made: a scale model of Uraniborg with its instruments can be found in the Deutsches Museum Munich, and full-scale models of some instruments exist in other museums (Denmark, Sweden, Czech Republic).

Stellaeburgum was restored in the 1960s. The Renaissance garden around the observatory is reconstructed.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:48:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Renaissance building of Uraniborg (influenced by Palladio, cf. Roslund et al. 2007) was very impressive, large and new - nothing similar to this observatory had existed before. The architecture of Uraniborg (Wolfschmidt 2010) may have been modelled on the symmetrical layout of Chambord Castle on the Loire (1539) or the buildings of the Italian Renaissance architects Andrea Palladio (1508-1580), or Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554) - particularly the Villa Rotonda (1552) in Vicenza near Venice.

A comparative study (İhsanoğlu 2004) shows the strong influence of Islamic instruments such as those of Maragha and Samarkand observatories, and that of Taqi al-Din used in Istanbul observatory, on Tycho’s. But the architecture of the observatory and the mounting was different.

The Round Tower in Copenhagen was inaugurated in 1642 as a replacement for Uraniborg’s astronomical functions.

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-09-05 19:49:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Tycho Brahe-Museet, Landsvägen 182 Ven

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 16:01:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Archenhold, Friedrich Simon & M. Albrecht: Ausgrabungen und Vermessungen der Sternwartenreste Tycho Brahes auf der Insel Hven. In: Das Weltall, Vorträge und Abhandlungen, Heft 9 (1902). Treptow bei Berlin, p. 1-20

- Arrest, Heinrich Louis d’: Die Ruinen von Uranienborg und Stjerneborg im Sommer 1868. In: Astronomische Nachrichten 72 (1868), Nr. 1718, p. 209-224.

Here you find the important information: 1 tychonic cubit = 39 cm, 1 tychonic foot = 25,9 cm - Beckett, Francis & Charles Christensen: Tycho Brahe’s Uraniborg und Stjerneborg on the Island of Hveen. London, Copenhagen 1921, p. 35-43, Abb. 1-9

- Blaeu, Willem Janszoon & Johann: Le theatre du monde ou nouvel Atlas (Theatrum orbis terrarum). 1635

- Blaeu, Johann: Geographia Blaviana Atlas Major. 11 vol. Amsterdam 1662

- Blaeu, Johann: Le Grand Atlas. 12 vol. Amsterdam 1663

- Brahe, Tycho: De mundi aetherei. Uraniborg 1588

- Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica. Wandsbek 1598

- Chapman, Allan: Astronomical Instruments and Their Users. Tycho Brahe to William Lassell. England (Collected Studies 530). Aldershot 1996

- Christianson, John Robert: Tycho Brahe. In: Carsten Bach-Nielsen (Red.): Danmark og renæssancen. 1500-1650. Copenhagen: Gad 2006

- Dreyer, John Louis Emil: Tycho Brahe. A Picture of Scientific Life and Work in the Sixteenth Century. Edinburgh 1890. New York, London: Dover 1963. Deutsche Übersetzung von M. Bruhns: Tycho Brahe. Ein Bild wissenschaftlichen Lebens und Arbeitens im sechzehnten Jahrhundert. Mit einem Vorwort von Wilhelm Valentiner. Karlsruhe 1894 (Reprint Vaduz/Lichtenstein 1992)

- Dreyer, John Louis Emil: Tychonis Brahe Dani Opera Omnia. Hg. von John Louis Emil Dreyer. 15 Vol. Kopenhagen 1913-1928

- İhsanoğlu, E.: The Introduction of Western Science to the Ottoman World: A Case Study of Modern Astronomy (1660-1860). In: Science, technology and learning in the Ottoman Empire: Western influence, local institutions, and the transfer of knowledge. Ed. by İhsanoğlu, E.; Aldershot, Hants, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company (Variorum Collected Studies) 2004

- Kwan, Alistair: Tycho’s Talisman: Astrological Magic in the Design of Uraniborg. In: Early Science and Medicine 16 (2011), p. 95-119

- Raeder, Hans; Strömgren, Elis & Bengt Strömgren: Tycho Brahe’s Description of his Instruments and Scientific Work as given in Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica. Wandesburgi (Wandsbek near Hamburg) 1598. Copenhagen 1946

- Rankl, Richard: Der Tychonische Sextant (von Bürgi) in der Sternwarte Kremsmünster. In: 89. Jahresbericht des Obergymnasiums der Benediktiner zu Kremsmünster. Linz 1946, p. 3-15

- Roslund, C.; Pásztor, Emília & G. Olofsson: Tycho Brahe’s Uraniborg: An Italian High Renaissance Villa. In: Papers from the annual meeting of SEAC (European Society for Astronomy in Culture) held in Kecskemét in Hungary in 2004. Ed. by Emília Pásztor. Oxford: Hadrian Books (BAR International Series 1647) 2007

- Šima, Zdislav: Prague Sextants of Tycho Brahe. In: Annals of Science 50 (1993), S. 445-453; vgl. Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society 35 (1992), p. 7-10

- Thoren, Victor E.: New Light on Tycho’s Instruments. In: Journal for the History of Astronomy 9 (1973), p. 25-45

- Wesley, Walter G.: The Accuracy of Tycho Brahe’s Instruments. In: Journal for the History of Astronomy 9 (1978), p. 42-53

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: All-Wissen - Tycho Brahes Sternwarte Uraniborg. In: Kultur und Technik 20 (1996), Heft 4, p. 12-13

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) - the Best Observing Astronomer in 16th Century. In: Schielicke, Reinhard E. (Hg.): Astronomische Gesellschaft - Abstract Series No. 12 (1996). Hamburg 1996, p. 123

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Tycho Brahe - Instrumentenbauer und Meister der Beobachtungstechnik. In: Florilegium Astronomicum. Festschrift für Felix Schmeidler. Hrsg. von Menso Folkerts, Stefan Kirschner, Theodor Schmidt-Kaler. München: Institut für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften (Algorismus, Heft 37) 2001, p. 293-323

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: The Observatories and Instruments of Tycho Brahe. In: Tycho Brahe and Prague: Crossroads of European Science. Proceedings of the International Symposium on the History of Science in the Rudolphine Period; Prague, 22-25 October 2001. Hrsg. von Christianson, John Robert; Hadravová, Alena; Hadrava, Petr and Martin Šolc. Frankfurt am Main: Harri Deutsch (Acta Historica Astronomiae Vol. 16) 2002, p. 203-216

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun & Martin Šolc: ,,Astronomy in and around Prague’’. Proceedings of the Colloquium of the Working Group for the History of Astronomy, Sept. 20, 2004, organized by Gudrun Wolfschmidt and Martin Šolc. Acta Universitatis Carolinae - Mathematica et Physica, Vol. 46, Supplementum (2005)

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Tycho Brahes Instrumente - historische Wurzeln, Innovation und Nachwirkung. In: Innovation durch Wissenstransfer in der Frühen Neuzeit. Kultur- und geistesgeschichtliche Studien zu Austauschprozessen in Mitteleuropa. Hg. von Johann Anselm Steiger, Sandra Richter und Marc Föcking. Amsterdam, New York: Rodopi B.V. (CHLOE Beihefte zum Daphnis; vol. 41) 2010, p. 249-278

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-09-05 19:50:51

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Tycho Brahe-Museet, Landsvägen 182 Ven

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-19 10:02:00

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Uraniborg 55° 54′ 28.3″ N, 12° 41′ 47.7″ E, elevation 44m above mean sea level.

Stjärneborg 55° 54′ 24.7″ N, 12° 41′ 49.3″ E, elevation 42m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 13:26:30

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

---

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 19

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:24:29

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Under the sponsorship of King Frederic II of Denmark (1534–1588), Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) built his observatory, called "Uraniborg", dedicated to Urania, the Muse of Astronomy (Wolfschmidt 2002a) on the Danish Island of Hven (today Ven, Swedish). It was the first time that a building was erected in Europe especially for the purpose of astronomical observations.

Fig. 1a. Uraniborg garden (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598) - Uraniborg observatory of Tycho Brahe (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1663)

Fig. 1b. Uraniborg garden (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598) - Uraniborg observatory of Tycho Brahe (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1663)

The brick building with sandstone and limestone frames was erected in 1576–1580 in the style of the Flemish Renaissance by the architect of the royal Danish court Hans van Steenwinckel der Ältere [Hans van Emden] (around 1545-1601) and the sculptor Johan Gregor van der Schardt (around 1530 - after 1581/91) in close cooperation with Tycho.

In the cellar was Tycho’s alchemical laboratory. The observatory measured 16m x 16m, with a 19m tower and two small round towers to the north and south of 6m diameter (with cone shaped roof), surrounded by galleries for the instruments.

A large mural quadrant affixed to a north-south wall, which was used to measure the altitude of stars as they passed the meridian, was situated inside the observatory. The engraving of the mural quadrant from Brahe’s book Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (1598) shows very well the ongoing work in the observatory.

The observatory is in the middle of the strongly geometrical Renaissance garden; in addition Tycho had a printing office and a water mill for making paper.

Fig. 2a. Tycho Brahe’s Stjerneborg, drawing by Willem Blaeu, circa 1595 (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1662, vol. 1)

Fig. 2b. Stjerneborg, today (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

In 1584 Tycho founded a second observatory, Stellaeburgum (Stjerneborg), 80m to the south of Uraniborg. In its five round towers with conical domes, called "crypts" by Tycho, his instruments were well protected against the wind.

Very striking is the similarity of Tycho’s instruments - the triquetrum, armillary sphere, sextant and quadrant, as described in his Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandsbek, 1598) - to those used in Islamic observatories by al-’Urdī in Marâgha observatory, or by al-Âmilî in Isfāhān and by Taqī al-Dīn in Istanbul observatory.

Tycho’s castle observatory Uraniborg was, at the end of the 16th century, an impressive advanced research centre both for studying astronomy and in respect of the innovative precise instruments.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 15

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:28:50

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 3a. Portrait of Tycho Brahe (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) was the most important observational astronomer until the invention of the telescope in 1608. From his astronomical observations, Tycho Brahe recognised the need to design and construct improved instruments. The question is whether tradition or progress prevails here (Wolfschmidt 2010). On the one hand, Tycho relied on the three important ancient instruments - the Quadrant, Triquetrum and Armillary Sphere - and rejected recent medieval developments such as the Astrolab and Torquetum; on the other hand he recognised the shortcomings and innovatively improved many features of classical instruments.

Fig. 3b. Quadrant, replica in castle Benátek (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Particularly noteworthy is the creation of novel instruments (Large Mural Quadrant 1582, sextants, semicircles) and the development of new measurement and reduction methods. As part of his observations of the nova in 1572 and the comet in 1577, Tycho overrode the current Aristotelian ideas. On the other hand, he also interpreted the comet in a classical way (astrologically) as a negative omen. With his Tychonic world system, he tried to strike a balance between the ancient geocentric view of the world and the Copernican world system.

Instruments (Wolfschmidt 2002)

By constructing new instruments and devising new observing methods, Tycho succeeded in significantly increasing measurement accuracy. He increased the size of his instruments (e.g. a large wooden quadrant of diameter 5.4m and a mural quadrant); he used metal and masonry rather than wood; he modified construction techniques to achieve greater stability; to provide shelter from the wind, his instruments were in subterranean nooks; his instruments were permanently and solidly mounted; and, for better angular readings, he developed new subdivisions and diopters (Tycho used transversals to obtain the greatest possible angular resolution readings). His instrumental sights (diopters) were specially designed to minimise errors; he carefully analysed all the errors (Tycho’s aim was to reduce the uncertainty to less than one minute of an arc); he used fundamental stars for the first time; he preferred measuring equatorial coordinates directly instead of using the zodiacal system, i.e. using the equatorial armillary sphere instead of the zodiacal armillary sphere; he tried out a new measuring method with clocks and his mural quadrant (1582) for determining the right ascension; and he took atmospheric refraction into account.

Most of his high-accuracy instruments have been destroyed. Only two sextants, made by Jost Bürgi (1552-1632) and Erasmus Habermel (c. 1538-1606) around 1600, still exist in the Národní Technické Muzeum (NTM) [National Technical Museum] in Prague. A model of the wooden quadrant is in the round tower of the old observatory in Copenhagen.

But we have good descriptions of the instruments (half-circles of 2.3m radius; quadrants up to 2m radius including the mural quadrant; sextants up to 1.6m; armillary spheres of 1.5m radius and the great equatorial armillary sphere of 2.7m; triquetrum and celestial globe of 1.5m) in Tycho’s book Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandesburgi 1598, Nuremberg 1602).

One of Tycho’s instruments was reconstructed in its original measurements in Oldenburg University and in the Steno Museum in Aarhus, Denmark. In Munich, in the Deutsches Museum’s permanent astronomy exhibition (opened in 1992), the Uraniborg observatory and its instruments are shown at a scale of 1:10. A similar but larger model (scale 1:5) from the workshop of the Deutsches Museum was given to the Technical Museum in Malmø, Sweden. Tycho’s later observatory Stjerneborg can be seen as a reconstruction on the island Hven (Ven/Sweden) with the original foundations for the instruments.

Fig. 4. Mural Quadrant, engraving of Tycho in his Uraniborg observatory (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 5a. Sextant, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 5b. observing with Sextant, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 5c. Armillary Sphere, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 6a. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6b. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6c. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6d. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 9

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 14:16:19

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 7a and 7b. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich (Photos: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Uraniborg no longer exists as an observatory (destroyed in 1601). But there is a very detailed description of the observatory and the instruments: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandsbek, 1598).

Fig. 8. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich with armillary sphere (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 9. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich with armillary spheres, sextant and triquetrum (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Some replicas were made: a scale model of Uraniborg with its instruments can be found in the Deutsches Museum Munich, and full-scale models of some instruments exist in other museums (Denmark, Sweden, Czech Republic).

Stellaeburgum was restored in the 1960s. The Renaissance garden around the observatory is reconstructed.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:48:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Renaissance building of Uraniborg (influenced by Palladio, cf. Roslund et al. 2007) was very impressive, large and new - nothing similar to this observatory had existed before. The architecture of Uraniborg (Wolfschmidt 2010) may have been modelled on the symmetrical layout of Chambord Castle on the Loire (1539) or the buildings of the Italian Renaissance architects Andrea Palladio (1508-1580), or Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554) - particularly the Villa Rotonda (1552) in Vicenza near Venice.

A comparative study (İhsanoğlu 2004) shows the strong influence of Islamic instruments such as those of Maragha and Samarkand observatories, and that of Taqi al-Din used in Istanbul observatory, on Tycho’s. But the architecture of the observatory and the mounting was different.

The Round Tower in Copenhagen was inaugurated in 1642 as a replacement for Uraniborg’s astronomical functions.

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-09-05 19:49:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Tycho Brahe-Museet, Landsvägen 182 Ven

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 16:01:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Archenhold, Friedrich Simon & M. Albrecht: Ausgrabungen und Vermessungen der Sternwartenreste Tycho Brahes auf der Insel Hven. In: Das Weltall, Vorträge und Abhandlungen, Heft 9 (1902). Treptow bei Berlin, p. 1-20

- Arrest, Heinrich Louis d’: Die Ruinen von Uranienborg und Stjerneborg im Sommer 1868. In: Astronomische Nachrichten 72 (1868), Nr. 1718, p. 209-224.

Here you find the important information: 1 tychonic cubit = 39 cm, 1 tychonic foot = 25,9 cm - Beckett, Francis & Charles Christensen: Tycho Brahe’s Uraniborg und Stjerneborg on the Island of Hveen. London, Copenhagen 1921, p. 35-43, Abb. 1-9

- Blaeu, Willem Janszoon & Johann: Le theatre du monde ou nouvel Atlas (Theatrum orbis terrarum). 1635

- Blaeu, Johann: Geographia Blaviana Atlas Major. 11 vol. Amsterdam 1662

- Blaeu, Johann: Le Grand Atlas. 12 vol. Amsterdam 1663

- Brahe, Tycho: De mundi aetherei. Uraniborg 1588

- Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica. Wandsbek 1598

- Chapman, Allan: Astronomical Instruments and Their Users. Tycho Brahe to William Lassell. England (Collected Studies 530). Aldershot 1996

- Christianson, John Robert: Tycho Brahe. In: Carsten Bach-Nielsen (Red.): Danmark og renæssancen. 1500-1650. Copenhagen: Gad 2006

- Dreyer, John Louis Emil: Tycho Brahe. A Picture of Scientific Life and Work in the Sixteenth Century. Edinburgh 1890. New York, London: Dover 1963. Deutsche Übersetzung von M. Bruhns: Tycho Brahe. Ein Bild wissenschaftlichen Lebens und Arbeitens im sechzehnten Jahrhundert. Mit einem Vorwort von Wilhelm Valentiner. Karlsruhe 1894 (Reprint Vaduz/Lichtenstein 1992)

- Dreyer, John Louis Emil: Tychonis Brahe Dani Opera Omnia. Hg. von John Louis Emil Dreyer. 15 Vol. Kopenhagen 1913-1928

- İhsanoğlu, E.: The Introduction of Western Science to the Ottoman World: A Case Study of Modern Astronomy (1660-1860). In: Science, technology and learning in the Ottoman Empire: Western influence, local institutions, and the transfer of knowledge. Ed. by İhsanoğlu, E.; Aldershot, Hants, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company (Variorum Collected Studies) 2004

- Kwan, Alistair: Tycho’s Talisman: Astrological Magic in the Design of Uraniborg. In: Early Science and Medicine 16 (2011), p. 95-119

- Raeder, Hans; Strömgren, Elis & Bengt Strömgren: Tycho Brahe’s Description of his Instruments and Scientific Work as given in Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica. Wandesburgi (Wandsbek near Hamburg) 1598. Copenhagen 1946

- Rankl, Richard: Der Tychonische Sextant (von Bürgi) in der Sternwarte Kremsmünster. In: 89. Jahresbericht des Obergymnasiums der Benediktiner zu Kremsmünster. Linz 1946, p. 3-15

- Roslund, C.; Pásztor, Emília & G. Olofsson: Tycho Brahe’s Uraniborg: An Italian High Renaissance Villa. In: Papers from the annual meeting of SEAC (European Society for Astronomy in Culture) held in Kecskemét in Hungary in 2004. Ed. by Emília Pásztor. Oxford: Hadrian Books (BAR International Series 1647) 2007

- Šima, Zdislav: Prague Sextants of Tycho Brahe. In: Annals of Science 50 (1993), S. 445-453; vgl. Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society 35 (1992), p. 7-10

- Thoren, Victor E.: New Light on Tycho’s Instruments. In: Journal for the History of Astronomy 9 (1973), p. 25-45

- Wesley, Walter G.: The Accuracy of Tycho Brahe’s Instruments. In: Journal for the History of Astronomy 9 (1978), p. 42-53

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: All-Wissen - Tycho Brahes Sternwarte Uraniborg. In: Kultur und Technik 20 (1996), Heft 4, p. 12-13

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) - the Best Observing Astronomer in 16th Century. In: Schielicke, Reinhard E. (Hg.): Astronomische Gesellschaft - Abstract Series No. 12 (1996). Hamburg 1996, p. 123

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Tycho Brahe - Instrumentenbauer und Meister der Beobachtungstechnik. In: Florilegium Astronomicum. Festschrift für Felix Schmeidler. Hrsg. von Menso Folkerts, Stefan Kirschner, Theodor Schmidt-Kaler. München: Institut für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften (Algorismus, Heft 37) 2001, p. 293-323

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: The Observatories and Instruments of Tycho Brahe. In: Tycho Brahe and Prague: Crossroads of European Science. Proceedings of the International Symposium on the History of Science in the Rudolphine Period; Prague, 22-25 October 2001. Hrsg. von Christianson, John Robert; Hadravová, Alena; Hadrava, Petr and Martin Šolc. Frankfurt am Main: Harri Deutsch (Acta Historica Astronomiae Vol. 16) 2002, p. 203-216

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun & Martin Šolc: ,,Astronomy in and around Prague’’. Proceedings of the Colloquium of the Working Group for the History of Astronomy, Sept. 20, 2004, organized by Gudrun Wolfschmidt and Martin Šolc. Acta Universitatis Carolinae - Mathematica et Physica, Vol. 46, Supplementum (2005)

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Tycho Brahes Instrumente - historische Wurzeln, Innovation und Nachwirkung. In: Innovation durch Wissenstransfer in der Frühen Neuzeit. Kultur- und geistesgeschichtliche Studien zu Austauschprozessen in Mitteleuropa. Hg. von Johann Anselm Steiger, Sandra Richter und Marc Föcking. Amsterdam, New York: Rodopi B.V. (CHLOE Beihefte zum Daphnis; vol. 41) 2010, p. 249-278

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-09-05 19:50:51

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Tycho Brahe-Museet, Landsvägen 182 Ven

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 13:26:30

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

---

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 19

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:24:29

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Under the sponsorship of King Frederic II of Denmark (1534–1588), Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) built his observatory, called "Uraniborg", dedicated to Urania, the Muse of Astronomy (Wolfschmidt 2002a) on the Danish Island of Hven (today Ven, Swedish). It was the first time that a building was erected in Europe especially for the purpose of astronomical observations.

Fig. 1a. Uraniborg garden (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598) - Uraniborg observatory of Tycho Brahe (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1663)

Fig. 1b. Uraniborg garden (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598) - Uraniborg observatory of Tycho Brahe (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1663)

The brick building with sandstone and limestone frames was erected in 1576–1580 in the style of the Flemish Renaissance by the architect of the royal Danish court Hans van Steenwinckel der Ältere [Hans van Emden] (around 1545-1601) and the sculptor Johan Gregor van der Schardt (around 1530 - after 1581/91) in close cooperation with Tycho.

In the cellar was Tycho’s alchemical laboratory. The observatory measured 16m x 16m, with a 19m tower and two small round towers to the north and south of 6m diameter (with cone shaped roof), surrounded by galleries for the instruments.

A large mural quadrant affixed to a north-south wall, which was used to measure the altitude of stars as they passed the meridian, was situated inside the observatory. The engraving of the mural quadrant from Brahe’s book Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (1598) shows very well the ongoing work in the observatory.

The observatory is in the middle of the strongly geometrical Renaissance garden; in addition Tycho had a printing office and a water mill for making paper.

Fig. 2a. Tycho Brahe’s Stjerneborg, drawing by Willem Blaeu, circa 1595 (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1662, vol. 1)

Fig. 2b. Stjerneborg, today (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

In 1584 Tycho founded a second observatory, Stellaeburgum (Stjerneborg), 80m to the south of Uraniborg. In its five round towers with conical domes, called "crypts" by Tycho, his instruments were well protected against the wind.

Very striking is the similarity of Tycho’s instruments - the triquetrum, armillary sphere, sextant and quadrant, as described in his Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandsbek, 1598) - to those used in Islamic observatories by al-’Urdī in Marâgha observatory, or by al-Âmilî in Isfāhān and by Taqī al-Dīn in Istanbul observatory.

Tycho’s castle observatory Uraniborg was, at the end of the 16th century, an impressive advanced research centre both for studying astronomy and in respect of the innovative precise instruments.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 15

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:28:50

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 3a. Portrait of Tycho Brahe (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) was the most important observational astronomer until the invention of the telescope in 1608. From his astronomical observations, Tycho Brahe recognised the need to design and construct improved instruments. The question is whether tradition or progress prevails here (Wolfschmidt 2010). On the one hand, Tycho relied on the three important ancient instruments - the Quadrant, Triquetrum and Armillary Sphere - and rejected recent medieval developments such as the Astrolab and Torquetum; on the other hand he recognised the shortcomings and innovatively improved many features of classical instruments.

Fig. 3b. Quadrant, replica in castle Benátek (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Particularly noteworthy is the creation of novel instruments (Large Mural Quadrant 1582, sextants, semicircles) and the development of new measurement and reduction methods. As part of his observations of the nova in 1572 and the comet in 1577, Tycho overrode the current Aristotelian ideas. On the other hand, he also interpreted the comet in a classical way (astrologically) as a negative omen. With his Tychonic world system, he tried to strike a balance between the ancient geocentric view of the world and the Copernican world system.

Instruments (Wolfschmidt 2002)

By constructing new instruments and devising new observing methods, Tycho succeeded in significantly increasing measurement accuracy. He increased the size of his instruments (e.g. a large wooden quadrant of diameter 5.4m and a mural quadrant); he used metal and masonry rather than wood; he modified construction techniques to achieve greater stability; to provide shelter from the wind, his instruments were in subterranean nooks; his instruments were permanently and solidly mounted; and, for better angular readings, he developed new subdivisions and diopters (Tycho used transversals to obtain the greatest possible angular resolution readings). His instrumental sights (diopters) were specially designed to minimise errors; he carefully analysed all the errors (Tycho’s aim was to reduce the uncertainty to less than one minute of an arc); he used fundamental stars for the first time; he preferred measuring equatorial coordinates directly instead of using the zodiacal system, i.e. using the equatorial armillary sphere instead of the zodiacal armillary sphere; he tried out a new measuring method with clocks and his mural quadrant (1582) for determining the right ascension; and he took atmospheric refraction into account.

Most of his high-accuracy instruments have been destroyed. Only two sextants, made by Jost Bürgi (1552-1632) and Erasmus Habermel (c. 1538-1606) around 1600, still exist in the Národní Technické Muzeum (NTM) [National Technical Museum] in Prague. A model of the wooden quadrant is in the round tower of the old observatory in Copenhagen.

But we have good descriptions of the instruments (half-circles of 2.3m radius; quadrants up to 2m radius including the mural quadrant; sextants up to 1.6m; armillary spheres of 1.5m radius and the great equatorial armillary sphere of 2.7m; triquetrum and celestial globe of 1.5m) in Tycho’s book Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandesburgi 1598, Nuremberg 1602).

One of Tycho’s instruments was reconstructed in its original measurements in Oldenburg University and in the Steno Museum in Aarhus, Denmark. In Munich, in the Deutsches Museum’s permanent astronomy exhibition (opened in 1992), the Uraniborg observatory and its instruments are shown at a scale of 1:10. A similar but larger model (scale 1:5) from the workshop of the Deutsches Museum was given to the Technical Museum in Malmø, Sweden. Tycho’s later observatory Stjerneborg can be seen as a reconstruction on the island Hven (Ven/Sweden) with the original foundations for the instruments.

Fig. 4. Mural Quadrant, engraving of Tycho in his Uraniborg observatory (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 5a. Sextant, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 5b. observing with Sextant, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 5c. Armillary Sphere, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 6a. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6b. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6c. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6d. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 9

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 14:16:19

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 7a and 7b. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich (Photos: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Uraniborg no longer exists as an observatory (destroyed in 1601). But there is a very detailed description of the observatory and the instruments: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandsbek, 1598).

Fig. 8. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich with armillary sphere (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 9. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich with armillary spheres, sextant and triquetrum (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Some replicas were made: a scale model of Uraniborg with its instruments can be found in the Deutsches Museum Munich, and full-scale models of some instruments exist in other museums (Denmark, Sweden, Czech Republic).

Stellaeburgum was restored in the 1960s. The Renaissance garden around the observatory is reconstructed.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:48:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Renaissance building of Uraniborg (influenced by Palladio, cf. Roslund et al. 2007) was very impressive, large and new - nothing similar to this observatory had existed before. The architecture of Uraniborg (Wolfschmidt 2010) may have been modelled on the symmetrical layout of Chambord Castle on the Loire (1539) or the buildings of the Italian Renaissance architects Andrea Palladio (1508-1580), or Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554) - particularly the Villa Rotonda (1552) in Vicenza near Venice.

A comparative study (İhsanoğlu 2004) shows the strong influence of Islamic instruments such as those of Maragha and Samarkand observatories, and that of Taqi al-Din used in Istanbul observatory, on Tycho’s. But the architecture of the observatory and the mounting was different.

The Round Tower in Copenhagen was inaugurated in 1642 as a replacement for Uraniborg’s astronomical functions.

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-09-05 19:49:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Tycho Brahe-Museet, Landsvägen 182 Ven

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 16:01:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Archenhold, Friedrich Simon & M. Albrecht: Ausgrabungen und Vermessungen der Sternwartenreste Tycho Brahes auf der Insel Hven. In: Das Weltall, Vorträge und Abhandlungen, Heft 9 (1902). Treptow bei Berlin, p. 1-20

- Arrest, Heinrich Louis d’: Die Ruinen von Uranienborg und Stjerneborg im Sommer 1868. In: Astronomische Nachrichten 72 (1868), Nr. 1718, p. 209-224.

Here you find the important information: 1 tychonic cubit = 39 cm, 1 tychonic foot = 25,9 cm - Beckett, Francis & Charles Christensen: Tycho Brahe’s Uraniborg und Stjerneborg on the Island of Hveen. London, Copenhagen 1921, p. 35-43, Abb. 1-9

- Blaeu, Willem Janszoon & Johann: Le theatre du monde ou nouvel Atlas (Theatrum orbis terrarum). 1635

- Blaeu, Johann: Geographia Blaviana Atlas Major. 11 vol. Amsterdam 1662

- Blaeu, Johann: Le Grand Atlas. 12 vol. Amsterdam 1663

- Brahe, Tycho: De mundi aetherei. Uraniborg 1588

- Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica. Wandsbek 1598

- Chapman, Allan: Astronomical Instruments and Their Users. Tycho Brahe to William Lassell. England (Collected Studies 530). Aldershot 1996

- Christianson, John Robert: Tycho Brahe. In: Carsten Bach-Nielsen (Red.): Danmark og renæssancen. 1500-1650. Copenhagen: Gad 2006

- Dreyer, John Louis Emil: Tycho Brahe. A Picture of Scientific Life and Work in the Sixteenth Century. Edinburgh 1890. New York, London: Dover 1963. Deutsche Übersetzung von M. Bruhns: Tycho Brahe. Ein Bild wissenschaftlichen Lebens und Arbeitens im sechzehnten Jahrhundert. Mit einem Vorwort von Wilhelm Valentiner. Karlsruhe 1894 (Reprint Vaduz/Lichtenstein 1992)

- Dreyer, John Louis Emil: Tychonis Brahe Dani Opera Omnia. Hg. von John Louis Emil Dreyer. 15 Vol. Kopenhagen 1913-1928

- İhsanoğlu, E.: The Introduction of Western Science to the Ottoman World: A Case Study of Modern Astronomy (1660-1860). In: Science, technology and learning in the Ottoman Empire: Western influence, local institutions, and the transfer of knowledge. Ed. by İhsanoğlu, E.; Aldershot, Hants, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company (Variorum Collected Studies) 2004

- Kwan, Alistair: Tycho’s Talisman: Astrological Magic in the Design of Uraniborg. In: Early Science and Medicine 16 (2011), p. 95-119

- Raeder, Hans; Strömgren, Elis & Bengt Strömgren: Tycho Brahe’s Description of his Instruments and Scientific Work as given in Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica. Wandesburgi (Wandsbek near Hamburg) 1598. Copenhagen 1946

- Rankl, Richard: Der Tychonische Sextant (von Bürgi) in der Sternwarte Kremsmünster. In: 89. Jahresbericht des Obergymnasiums der Benediktiner zu Kremsmünster. Linz 1946, p. 3-15

- Roslund, C.; Pásztor, Emília & G. Olofsson: Tycho Brahe’s Uraniborg: An Italian High Renaissance Villa. In: Papers from the annual meeting of SEAC (European Society for Astronomy in Culture) held in Kecskemét in Hungary in 2004. Ed. by Emília Pásztor. Oxford: Hadrian Books (BAR International Series 1647) 2007

- Šima, Zdislav: Prague Sextants of Tycho Brahe. In: Annals of Science 50 (1993), S. 445-453; vgl. Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society 35 (1992), p. 7-10

- Thoren, Victor E.: New Light on Tycho’s Instruments. In: Journal for the History of Astronomy 9 (1973), p. 25-45

- Wesley, Walter G.: The Accuracy of Tycho Brahe’s Instruments. In: Journal for the History of Astronomy 9 (1978), p. 42-53

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: All-Wissen - Tycho Brahes Sternwarte Uraniborg. In: Kultur und Technik 20 (1996), Heft 4, p. 12-13

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) - the Best Observing Astronomer in 16th Century. In: Schielicke, Reinhard E. (Hg.): Astronomische Gesellschaft - Abstract Series No. 12 (1996). Hamburg 1996, p. 123

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Tycho Brahe - Instrumentenbauer und Meister der Beobachtungstechnik. In: Florilegium Astronomicum. Festschrift für Felix Schmeidler. Hrsg. von Menso Folkerts, Stefan Kirschner, Theodor Schmidt-Kaler. München: Institut für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften (Algorismus, Heft 37) 2001, p. 293-323

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: The Observatories and Instruments of Tycho Brahe. In: Tycho Brahe and Prague: Crossroads of European Science. Proceedings of the International Symposium on the History of Science in the Rudolphine Period; Prague, 22-25 October 2001. Hrsg. von Christianson, John Robert; Hadravová, Alena; Hadrava, Petr and Martin Šolc. Frankfurt am Main: Harri Deutsch (Acta Historica Astronomiae Vol. 16) 2002, p. 203-216

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun & Martin Šolc: ,,Astronomy in and around Prague’’. Proceedings of the Colloquium of the Working Group for the History of Astronomy, Sept. 20, 2004, organized by Gudrun Wolfschmidt and Martin Šolc. Acta Universitatis Carolinae - Mathematica et Physica, Vol. 46, Supplementum (2005)

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Tycho Brahes Instrumente - historische Wurzeln, Innovation und Nachwirkung. In: Innovation durch Wissenstransfer in der Frühen Neuzeit. Kultur- und geistesgeschichtliche Studien zu Austauschprozessen in Mitteleuropa. Hg. von Johann Anselm Steiger, Sandra Richter und Marc Föcking. Amsterdam, New York: Rodopi B.V. (CHLOE Beihefte zum Daphnis; vol. 41) 2010, p. 249-278

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-09-05 19:50:51

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Tycho Brahe-Museet, Landsvägen 182 Ven

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 19

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:24:29

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Under the sponsorship of King Frederic II of Denmark (1534–1588), Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) built his observatory, called "Uraniborg", dedicated to Urania, the Muse of Astronomy (Wolfschmidt 2002a) on the Danish Island of Hven (today Ven, Swedish). It was the first time that a building was erected in Europe especially for the purpose of astronomical observations.

Fig. 1a. Uraniborg garden (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598) - Uraniborg observatory of Tycho Brahe (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1663)

Fig. 1b. Uraniborg garden (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598) - Uraniborg observatory of Tycho Brahe (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1663)

The brick building with sandstone and limestone frames was erected in 1576–1580 in the style of the Flemish Renaissance by the architect of the royal Danish court Hans van Steenwinckel der Ältere [Hans van Emden] (around 1545-1601) and the sculptor Johan Gregor van der Schardt (around 1530 - after 1581/91) in close cooperation with Tycho.

In the cellar was Tycho’s alchemical laboratory. The observatory measured 16m x 16m, with a 19m tower and two small round towers to the north and south of 6m diameter (with cone shaped roof), surrounded by galleries for the instruments.

A large mural quadrant affixed to a north-south wall, which was used to measure the altitude of stars as they passed the meridian, was situated inside the observatory. The engraving of the mural quadrant from Brahe’s book Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (1598) shows very well the ongoing work in the observatory.

The observatory is in the middle of the strongly geometrical Renaissance garden; in addition Tycho had a printing office and a water mill for making paper.

Fig. 2a. Tycho Brahe’s Stjerneborg, drawing by Willem Blaeu, circa 1595 (Blaeu, Johan: Atlas Major. Amsterdam 1662, vol. 1)

Fig. 2b. Stjerneborg, today (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

In 1584 Tycho founded a second observatory, Stellaeburgum (Stjerneborg), 80m to the south of Uraniborg. In its five round towers with conical domes, called "crypts" by Tycho, his instruments were well protected against the wind.

Very striking is the similarity of Tycho’s instruments - the triquetrum, armillary sphere, sextant and quadrant, as described in his Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandsbek, 1598) - to those used in Islamic observatories by al-’Urdī in Marâgha observatory, or by al-Âmilî in Isfāhān and by Taqī al-Dīn in Istanbul observatory.

Tycho’s castle observatory Uraniborg was, at the end of the 16th century, an impressive advanced research centre both for studying astronomy and in respect of the innovative precise instruments.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 15

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:28:50

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 3a. Portrait of Tycho Brahe (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) was the most important observational astronomer until the invention of the telescope in 1608. From his astronomical observations, Tycho Brahe recognised the need to design and construct improved instruments. The question is whether tradition or progress prevails here (Wolfschmidt 2010). On the one hand, Tycho relied on the three important ancient instruments - the Quadrant, Triquetrum and Armillary Sphere - and rejected recent medieval developments such as the Astrolab and Torquetum; on the other hand he recognised the shortcomings and innovatively improved many features of classical instruments.

Fig. 3b. Quadrant, replica in castle Benátek (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Particularly noteworthy is the creation of novel instruments (Large Mural Quadrant 1582, sextants, semicircles) and the development of new measurement and reduction methods. As part of his observations of the nova in 1572 and the comet in 1577, Tycho overrode the current Aristotelian ideas. On the other hand, he also interpreted the comet in a classical way (astrologically) as a negative omen. With his Tychonic world system, he tried to strike a balance between the ancient geocentric view of the world and the Copernican world system.

Instruments (Wolfschmidt 2002)

By constructing new instruments and devising new observing methods, Tycho succeeded in significantly increasing measurement accuracy. He increased the size of his instruments (e.g. a large wooden quadrant of diameter 5.4m and a mural quadrant); he used metal and masonry rather than wood; he modified construction techniques to achieve greater stability; to provide shelter from the wind, his instruments were in subterranean nooks; his instruments were permanently and solidly mounted; and, for better angular readings, he developed new subdivisions and diopters (Tycho used transversals to obtain the greatest possible angular resolution readings). His instrumental sights (diopters) were specially designed to minimise errors; he carefully analysed all the errors (Tycho’s aim was to reduce the uncertainty to less than one minute of an arc); he used fundamental stars for the first time; he preferred measuring equatorial coordinates directly instead of using the zodiacal system, i.e. using the equatorial armillary sphere instead of the zodiacal armillary sphere; he tried out a new measuring method with clocks and his mural quadrant (1582) for determining the right ascension; and he took atmospheric refraction into account.

Most of his high-accuracy instruments have been destroyed. Only two sextants, made by Jost Bürgi (1552-1632) and Erasmus Habermel (c. 1538-1606) around 1600, still exist in the Národní Technické Muzeum (NTM) [National Technical Museum] in Prague. A model of the wooden quadrant is in the round tower of the old observatory in Copenhagen.

But we have good descriptions of the instruments (half-circles of 2.3m radius; quadrants up to 2m radius including the mural quadrant; sextants up to 1.6m; armillary spheres of 1.5m radius and the great equatorial armillary sphere of 2.7m; triquetrum and celestial globe of 1.5m) in Tycho’s book Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandesburgi 1598, Nuremberg 1602).

One of Tycho’s instruments was reconstructed in its original measurements in Oldenburg University and in the Steno Museum in Aarhus, Denmark. In Munich, in the Deutsches Museum’s permanent astronomy exhibition (opened in 1992), the Uraniborg observatory and its instruments are shown at a scale of 1:10. A similar but larger model (scale 1:5) from the workshop of the Deutsches Museum was given to the Technical Museum in Malmø, Sweden. Tycho’s later observatory Stjerneborg can be seen as a reconstruction on the island Hven (Ven/Sweden) with the original foundations for the instruments.

Fig. 4. Mural Quadrant, engraving of Tycho in his Uraniborg observatory (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 5a. Sextant, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 5b. observing with Sextant, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 5c. Armillary Sphere, Tycho’s observatory in Castle Benátek (Benatky) near Prag (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 6a. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6b. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6c. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

Fig. 6d. Uraniborg, alchemical laboratory and instruments (Brahe, Tycho: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1598)

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 9

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 14:16:19

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 7a and 7b. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich (Photos: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Uraniborg no longer exists as an observatory (destroyed in 1601). But there is a very detailed description of the observatory and the instruments: Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandsbek, 1598).

Fig. 8. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich with armillary sphere (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 9. Uraniborg, model in the Deutsches Museum Munich with armillary spheres, sextant and triquetrum (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Some replicas were made: a scale model of Uraniborg with its instruments can be found in the Deutsches Museum Munich, and full-scale models of some instruments exist in other museums (Denmark, Sweden, Czech Republic).

Stellaeburgum was restored in the 1960s. The Renaissance garden around the observatory is reconstructed.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 100

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-11-23 15:48:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Renaissance building of Uraniborg (influenced by Palladio, cf. Roslund et al. 2007) was very impressive, large and new - nothing similar to this observatory had existed before. The architecture of Uraniborg (Wolfschmidt 2010) may have been modelled on the symmetrical layout of Chambord Castle on the Loire (1539) or the buildings of the Italian Renaissance architects Andrea Palladio (1508-1580), or Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554) - particularly the Villa Rotonda (1552) in Vicenza near Venice.