Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Hevelius observatory, Danzig, Poland

Format: IAU - Outstanding Astronomical Heritage

Description

Geographical position - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-08-09 07:01:07

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Danzig / Gdańsk, Pfefferstadt, ulica Korzenna, houses No 47, 48 and 49 (not 53, 54 and 55) -

near the old city hall (Altstädtisches Rathaus) and church St. Bartholomäus.

Location - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 17:12:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Lat. 54° 21′ 15″ N, long. 18° 38′ 54″ E, elevation 33m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 12:34:35

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

A51

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:26:59

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Observatories of Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687)

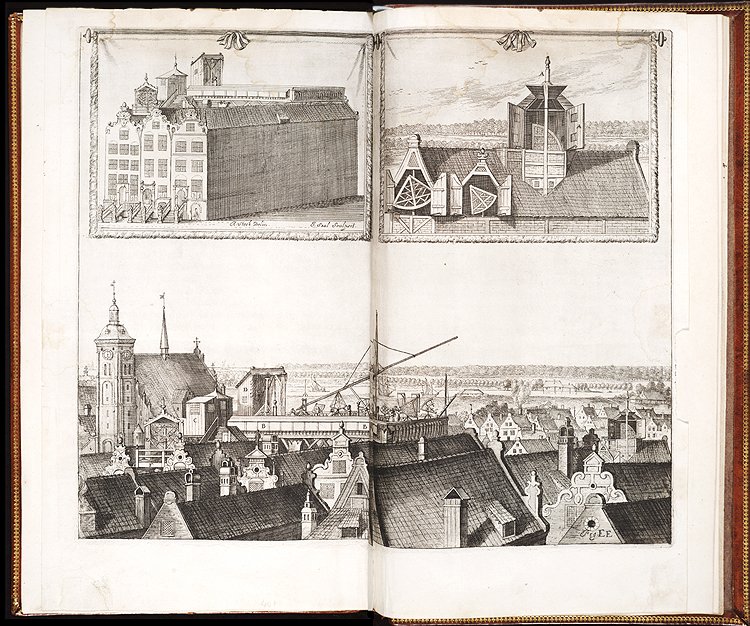

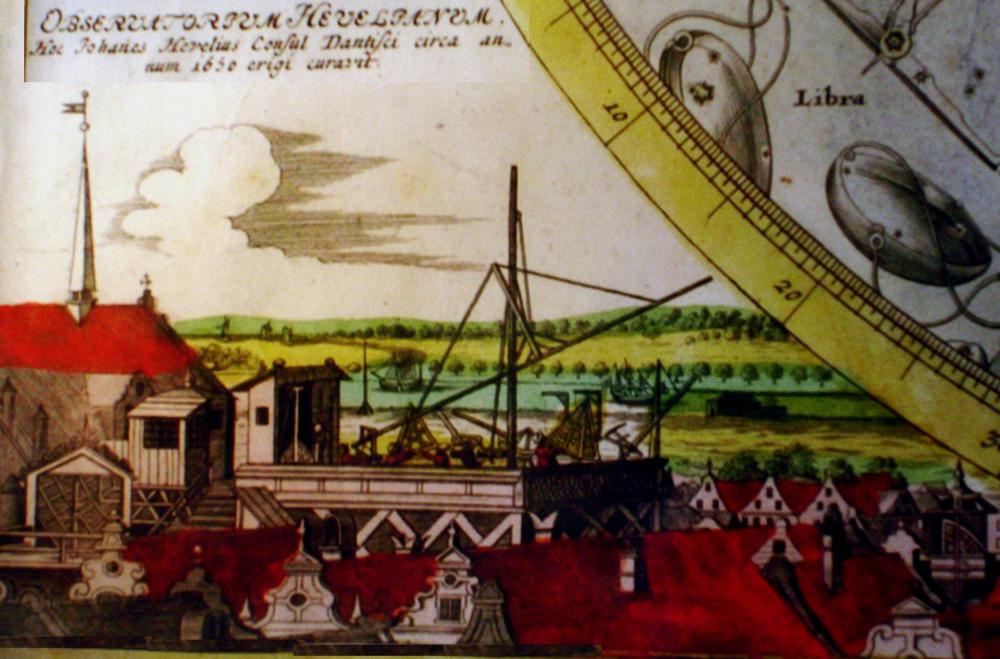

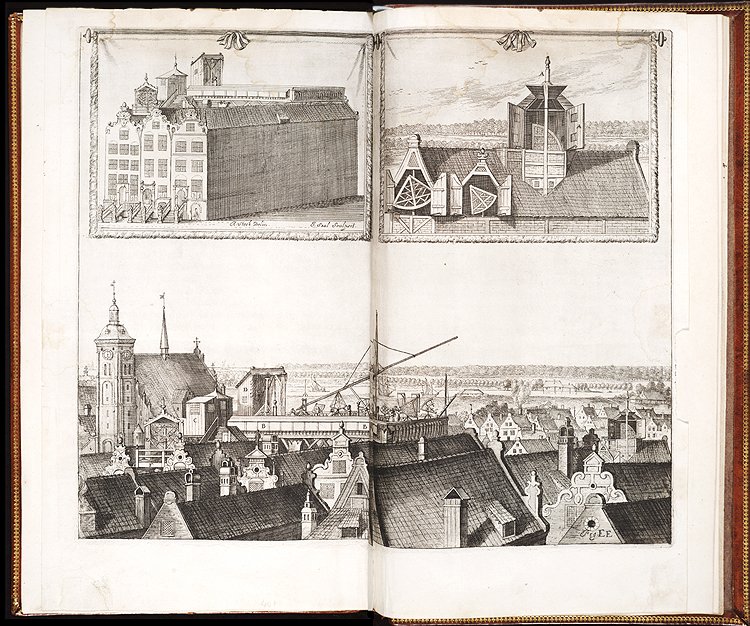

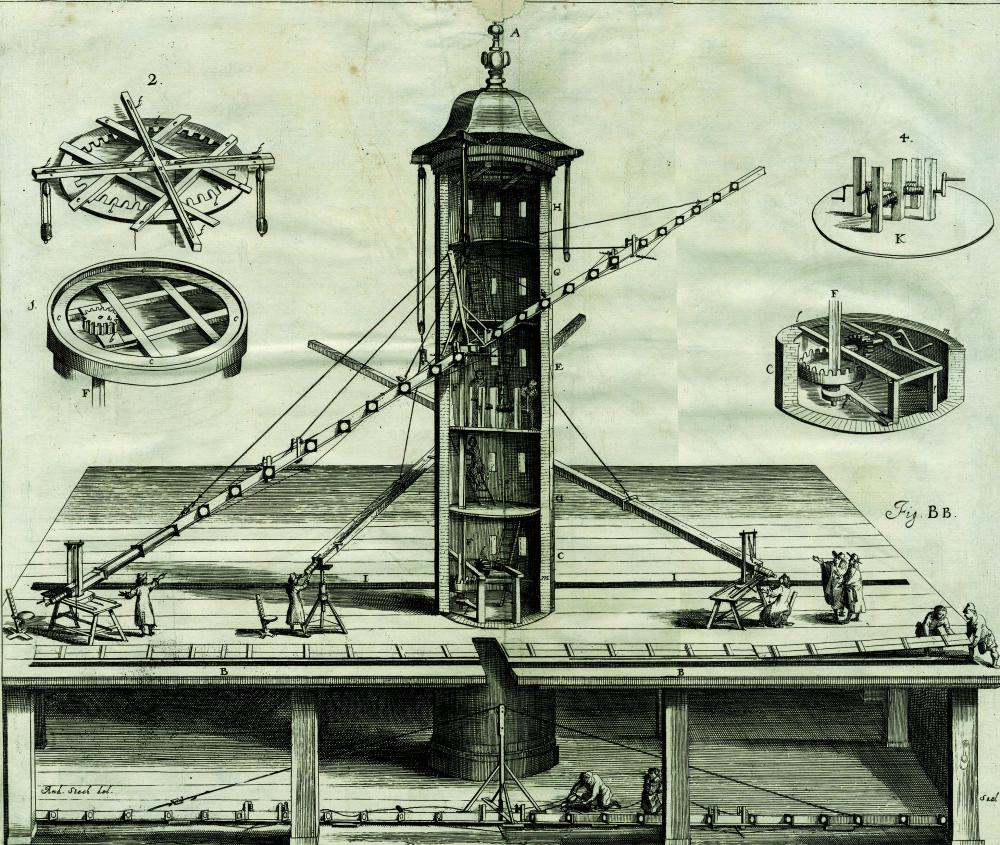

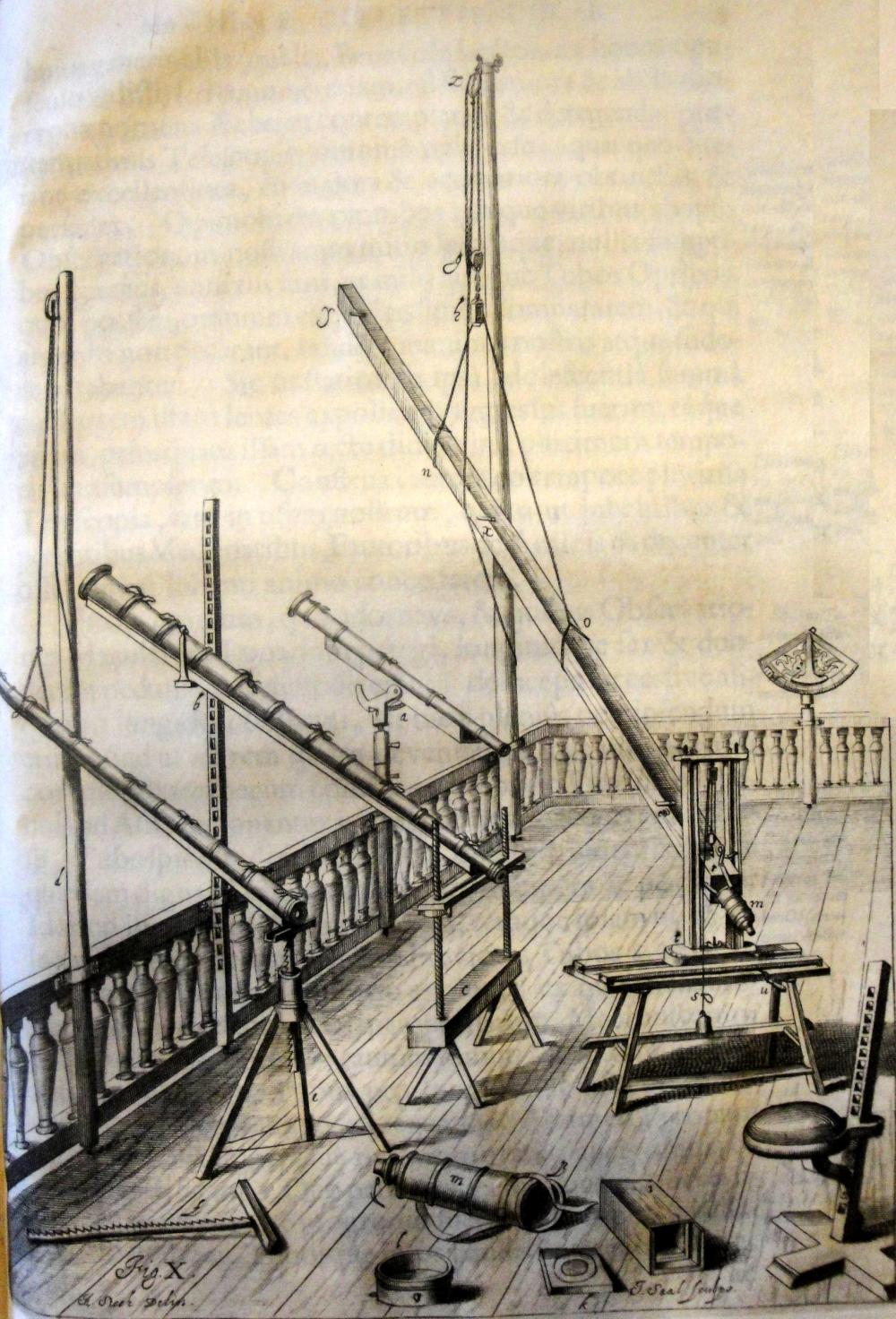

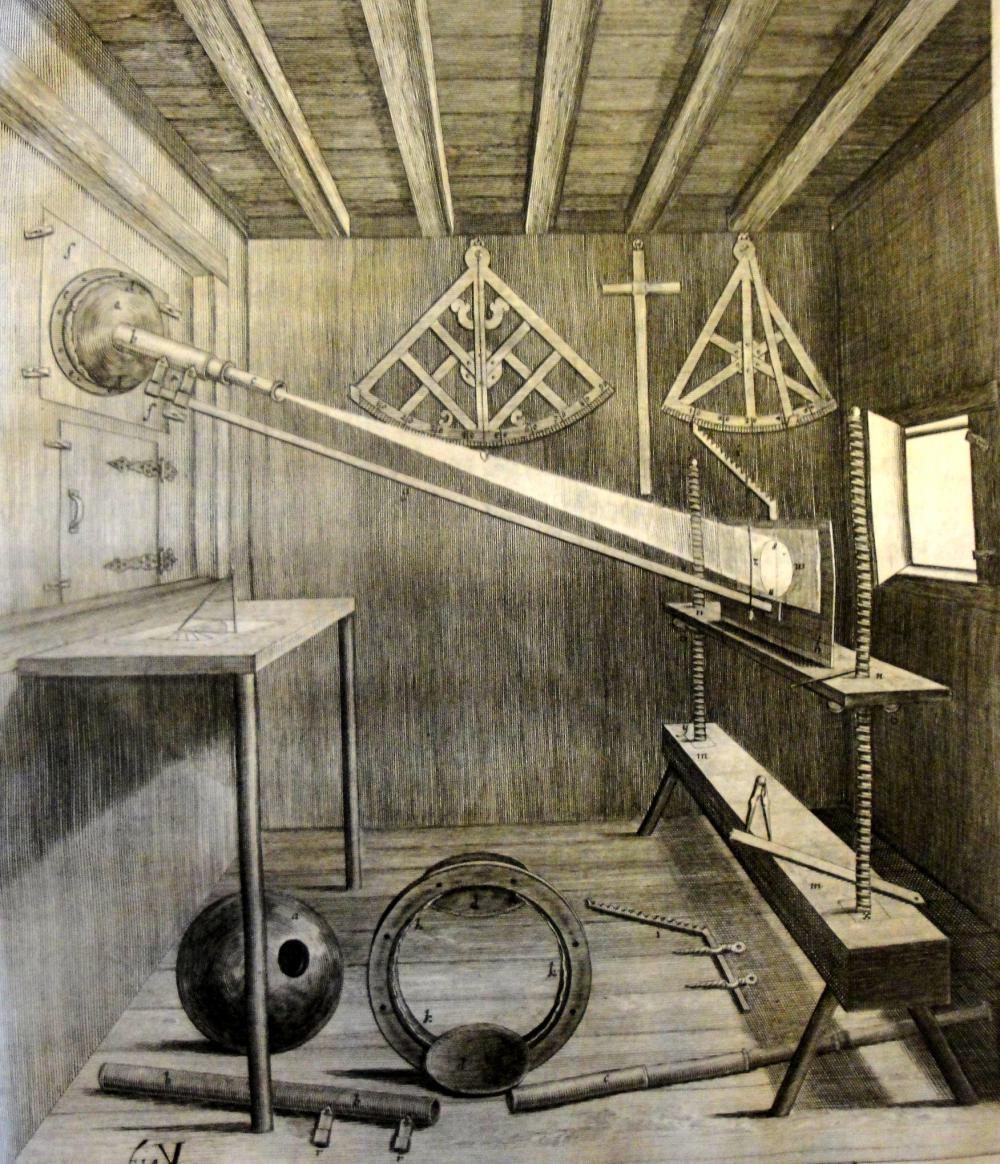

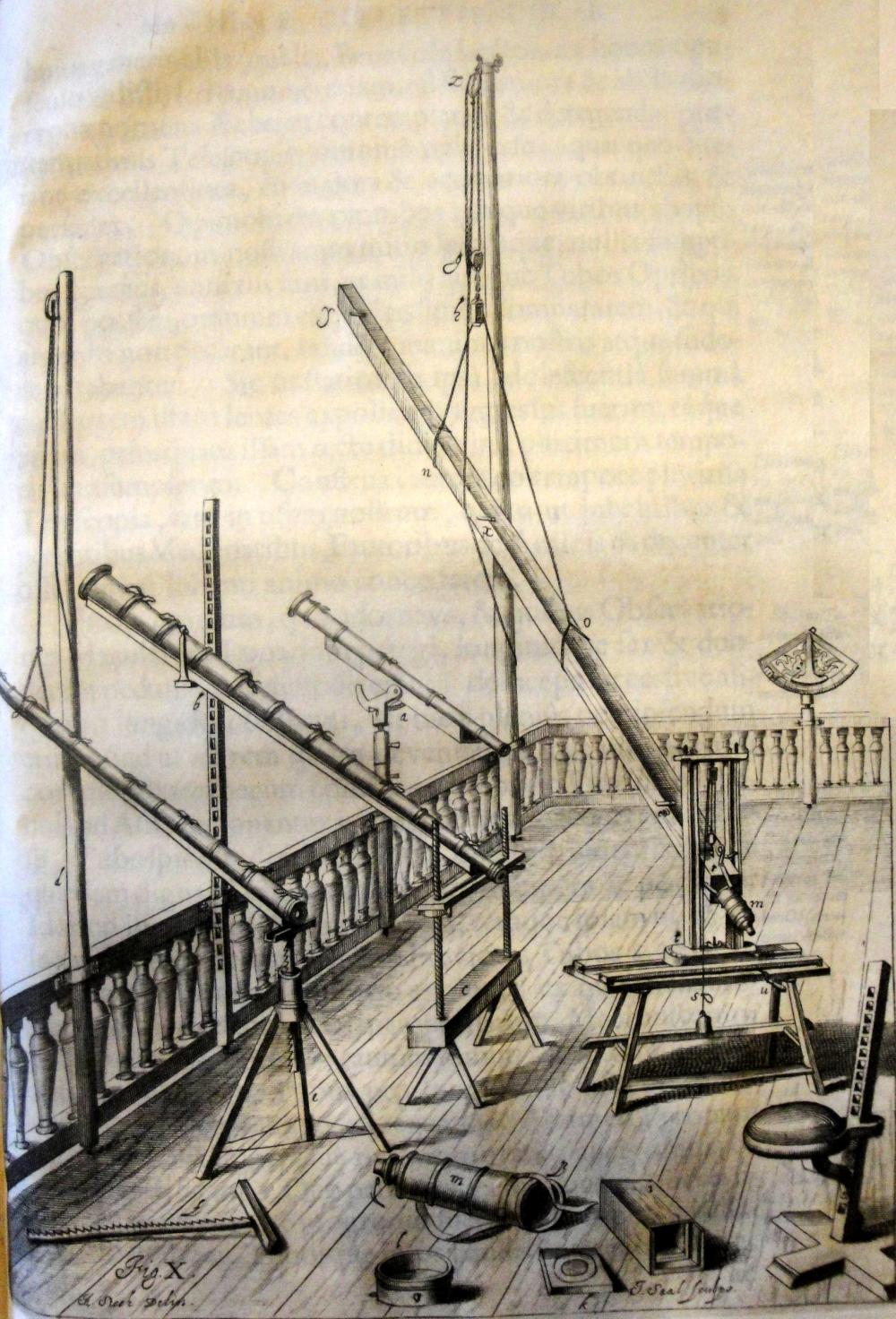

For his instruments, Johannes Hevelius [Hewelcke, Polish Jan Heweliusz] (1611--1687) was very much inspired by Tycho Brahe (1546--1601), but concerning his private observatory, Hevelius had to choose a reasonably priced solution because he had no patron. Until the construction of the observatories in Greenwich and Paris in the 1670s, it was also the largest in Europe. Hevelius’ observatory developed parallel to the progress of its astronomical instruments.

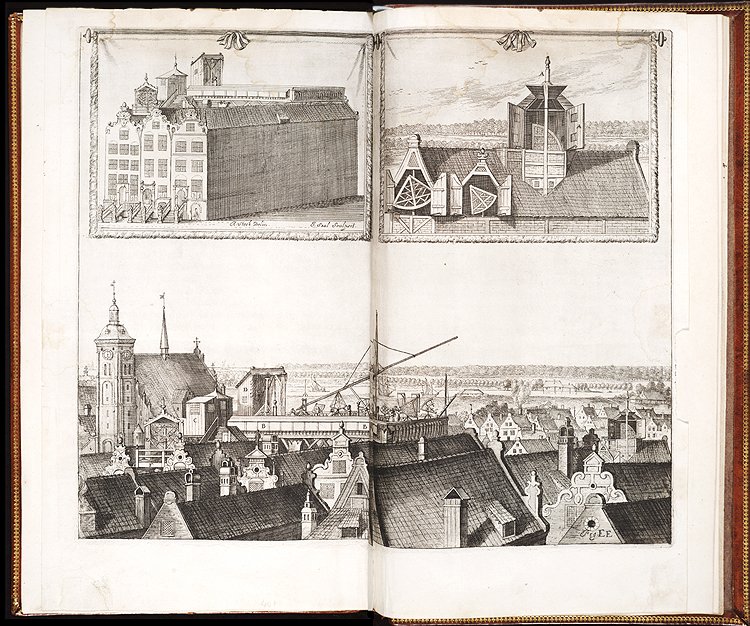

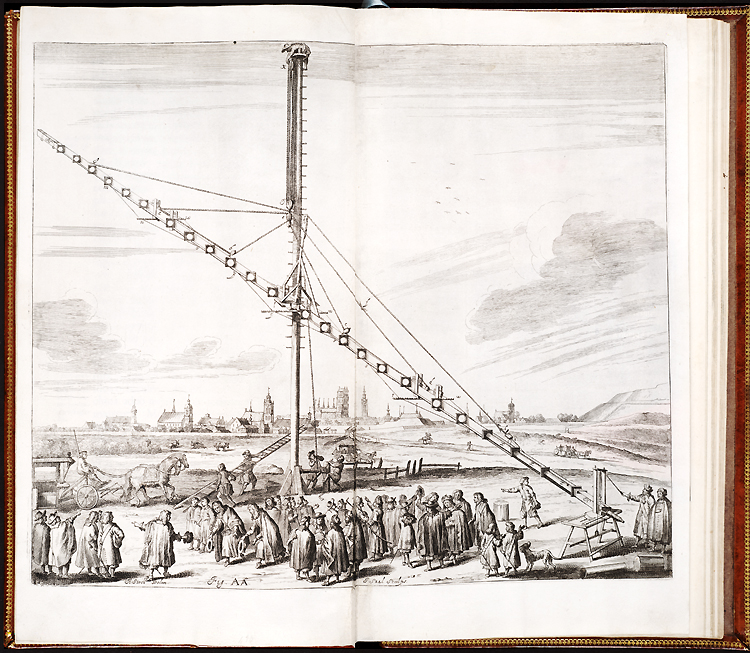

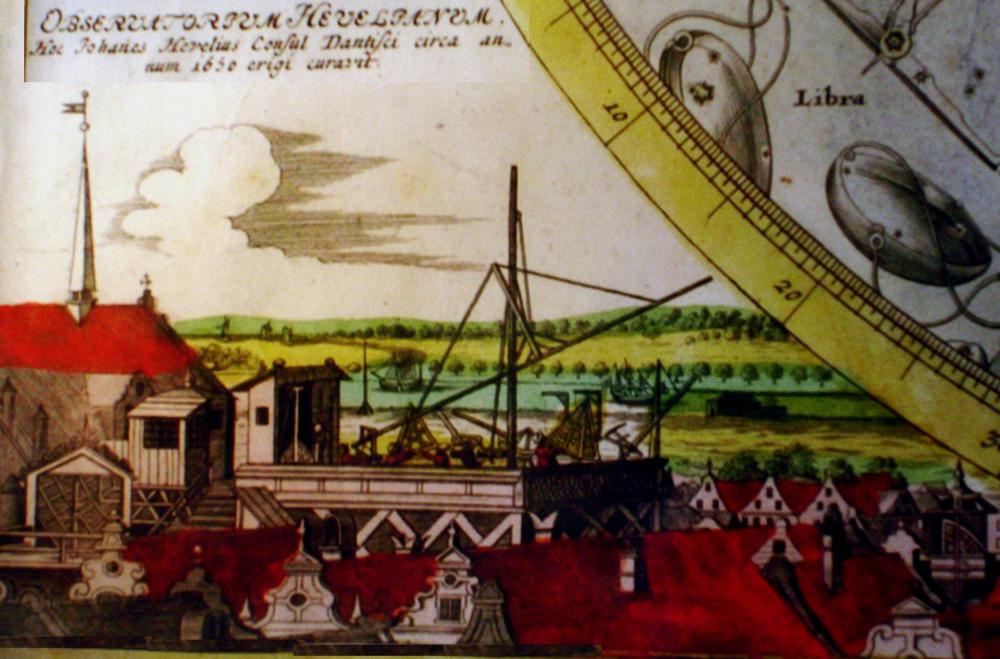

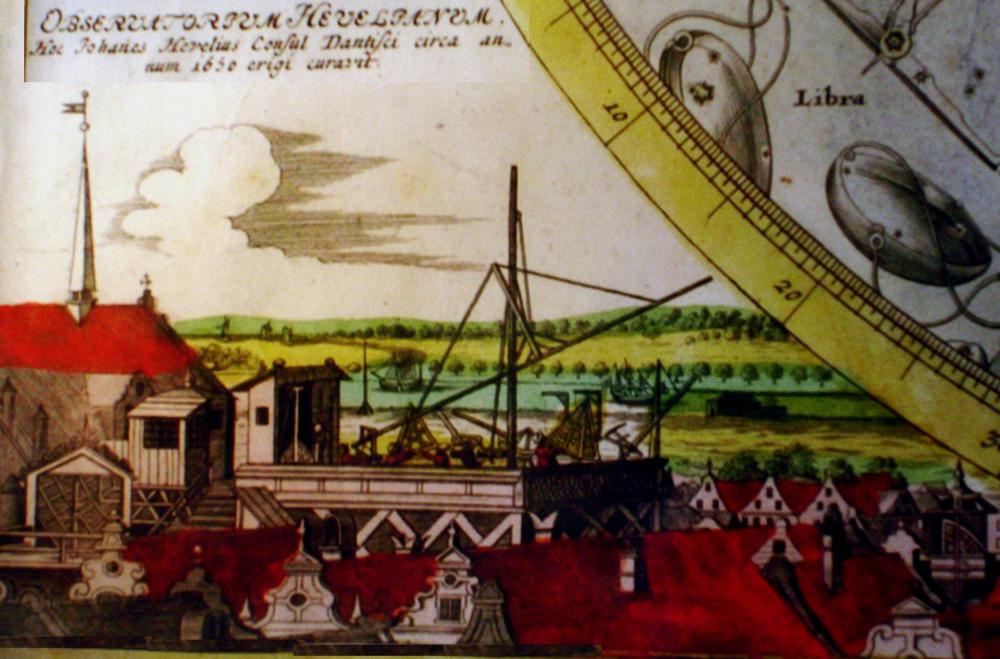

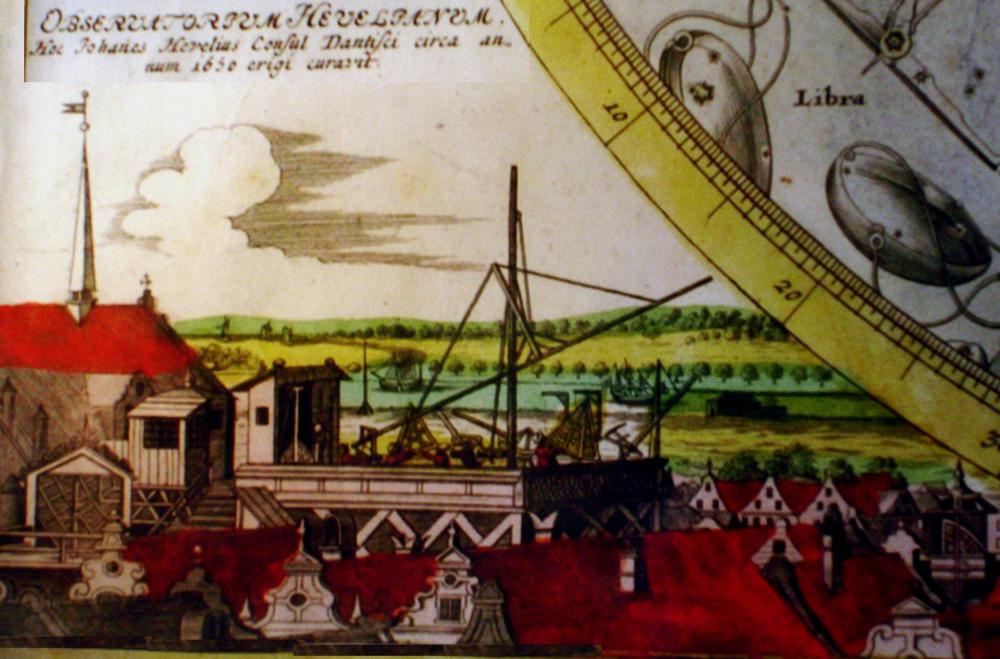

Fig. 1. Observatories of Johannes Hevelius (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

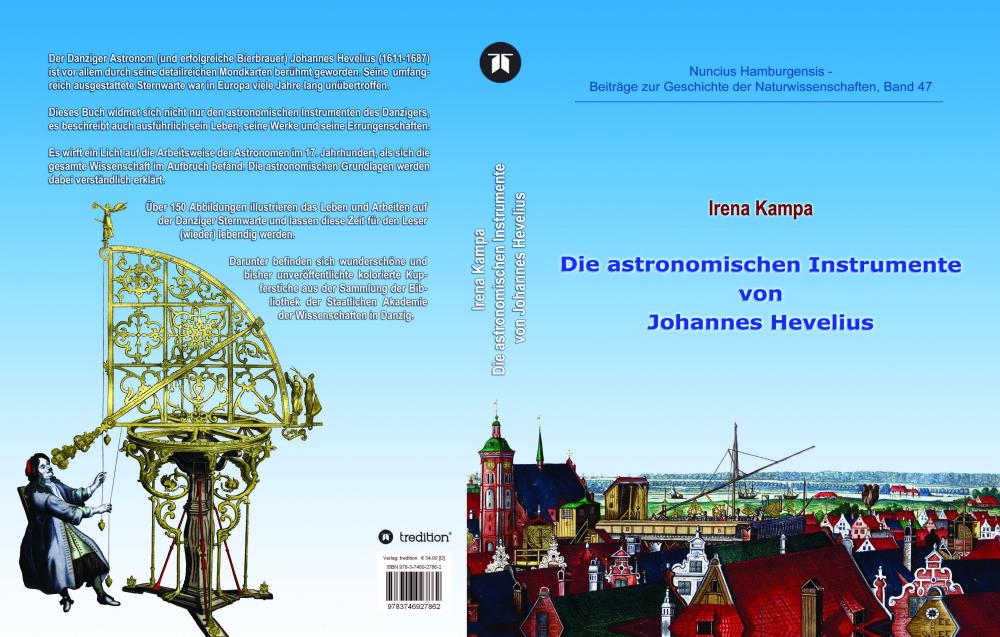

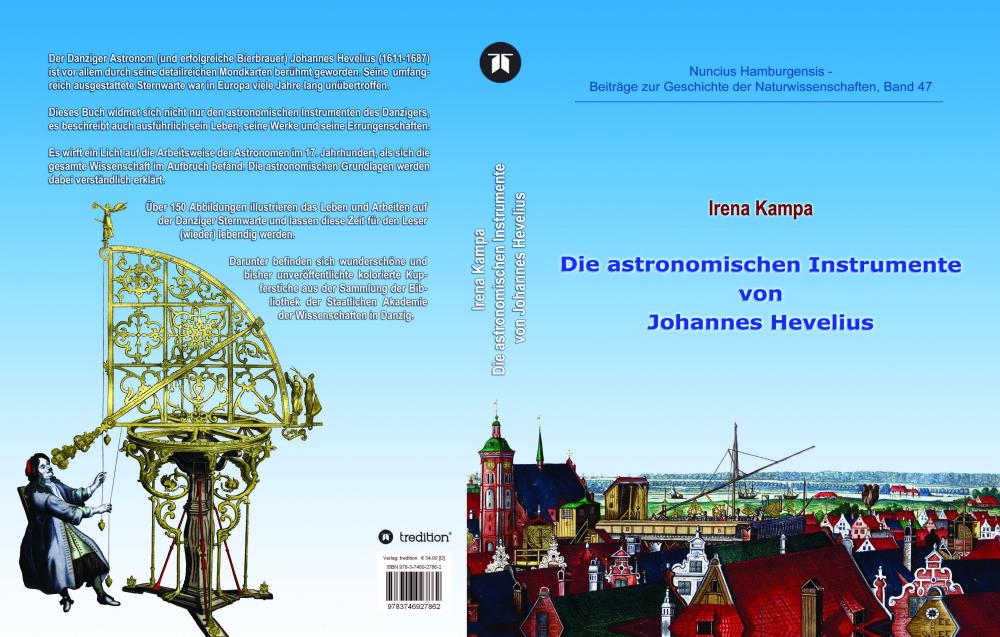

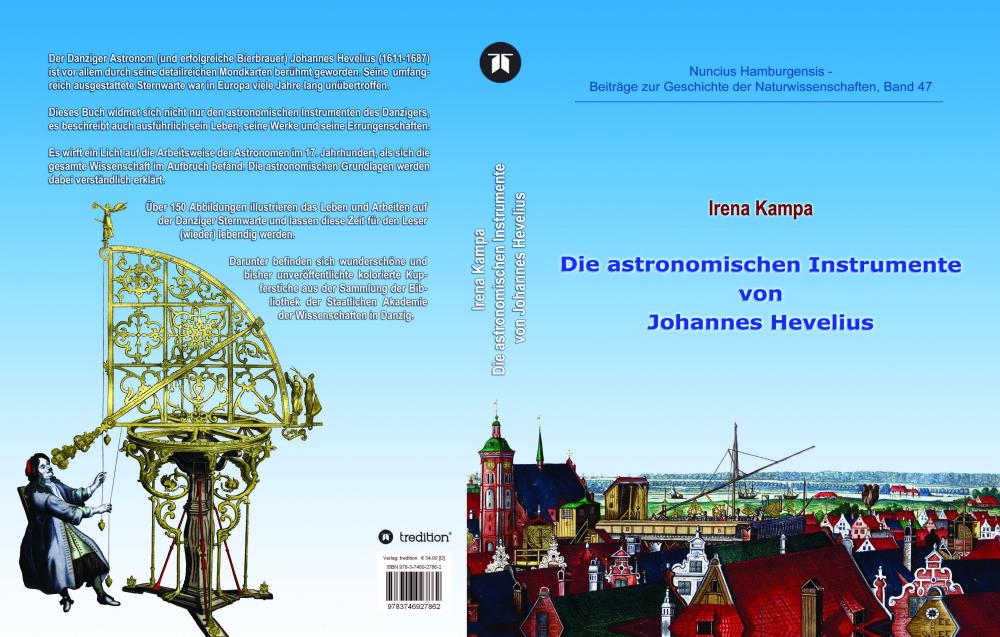

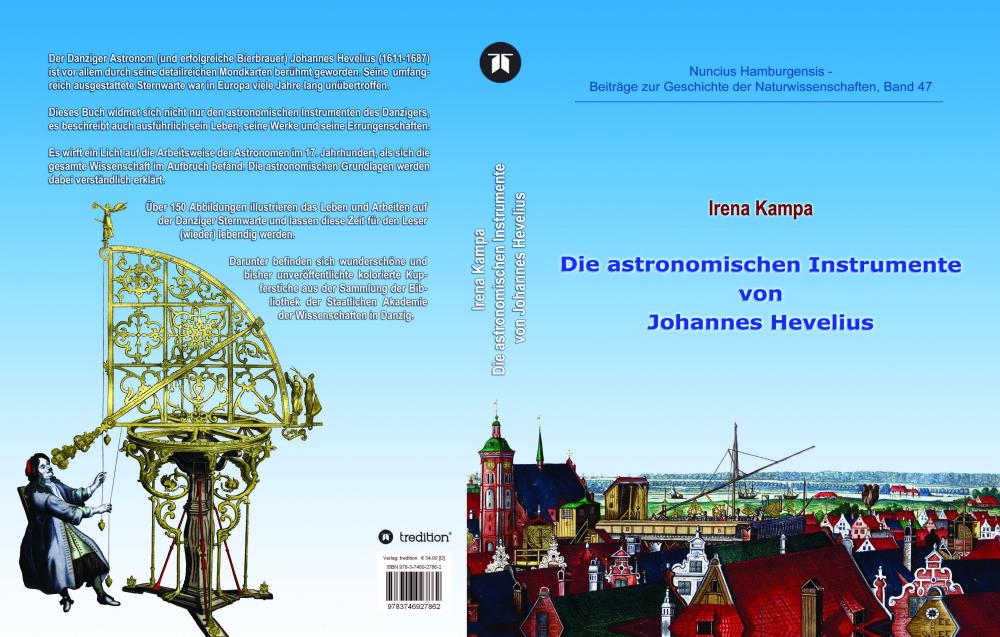

Irena Kampa (2017) describes in her thesis in great detail the astronomical instruments and compares them with instruments of other contemporary astronomers. Hevelius’ correspondence with European scientists served as the main source to find the makers of his devices. An examination of 22,000 single observational data provides new information about the usage of his instruments.

Fig. 2. Cover of the book of Kampa (2018)

Hevelius’ first observatory (1641)

In the beginning Hevelius did not have a fixed observing post but was star gazing from two nearby church towers with portable instruments.

In 1641, for his first observatory, he used four large roof windows for the small brass and also for the larger wooden instruments and also the big wooden instruments. In 1644 Hevelius received from the estate of his teacher Peter Crüger (1580-1639) the large azimuth quadrant; this instrument required a precise north-south orientation. Hevelius built a tower of octagonal shape with a diameter of 12 feet (about 3.3m) for this large wooden quadrant. For measuring time during observations Hevelius counted pendulum swings. He even constructed a machine to count them but was overtaken by Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695) and his patent on the pendulum clock.

Fig. 3. Hevelius observing with the quadrant and pendulum-clocks (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Fig. 4. Hevelius roof observatory, model in the Deutsches Musem (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

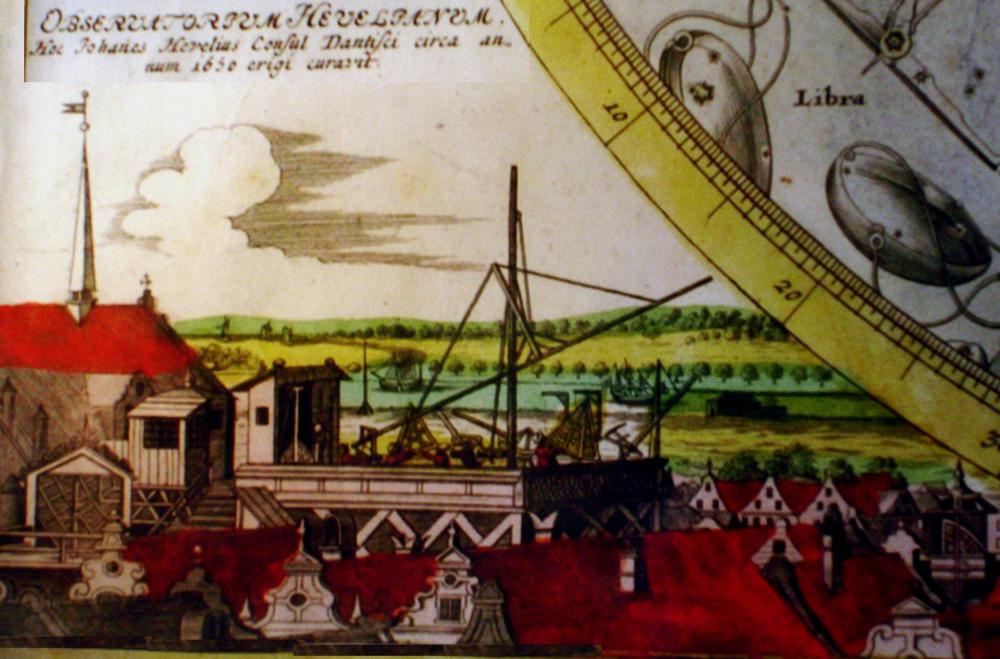

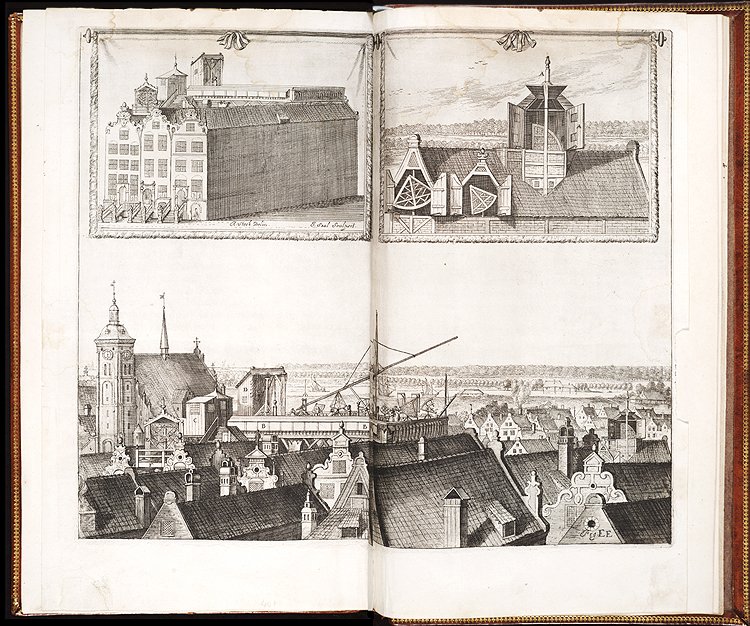

Hevelius’ Stellaburgum - Hevelius’ second observatory (1650)

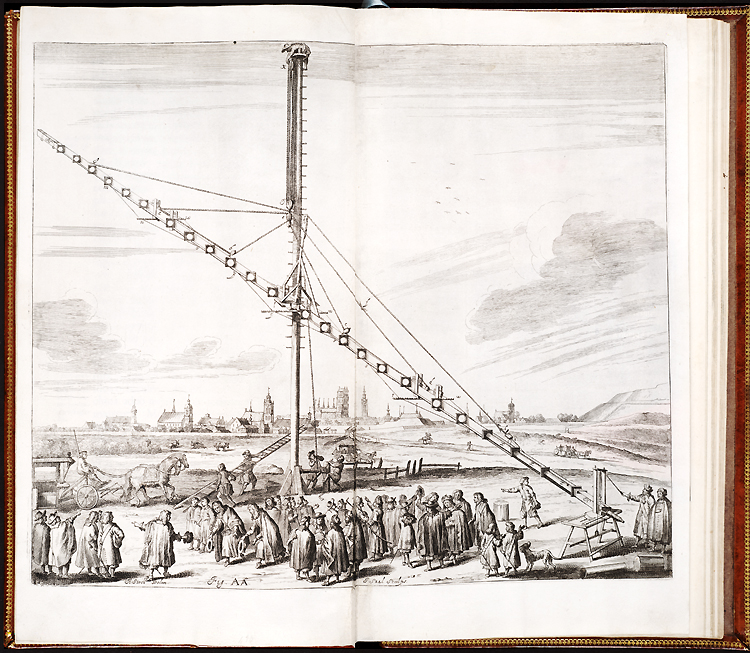

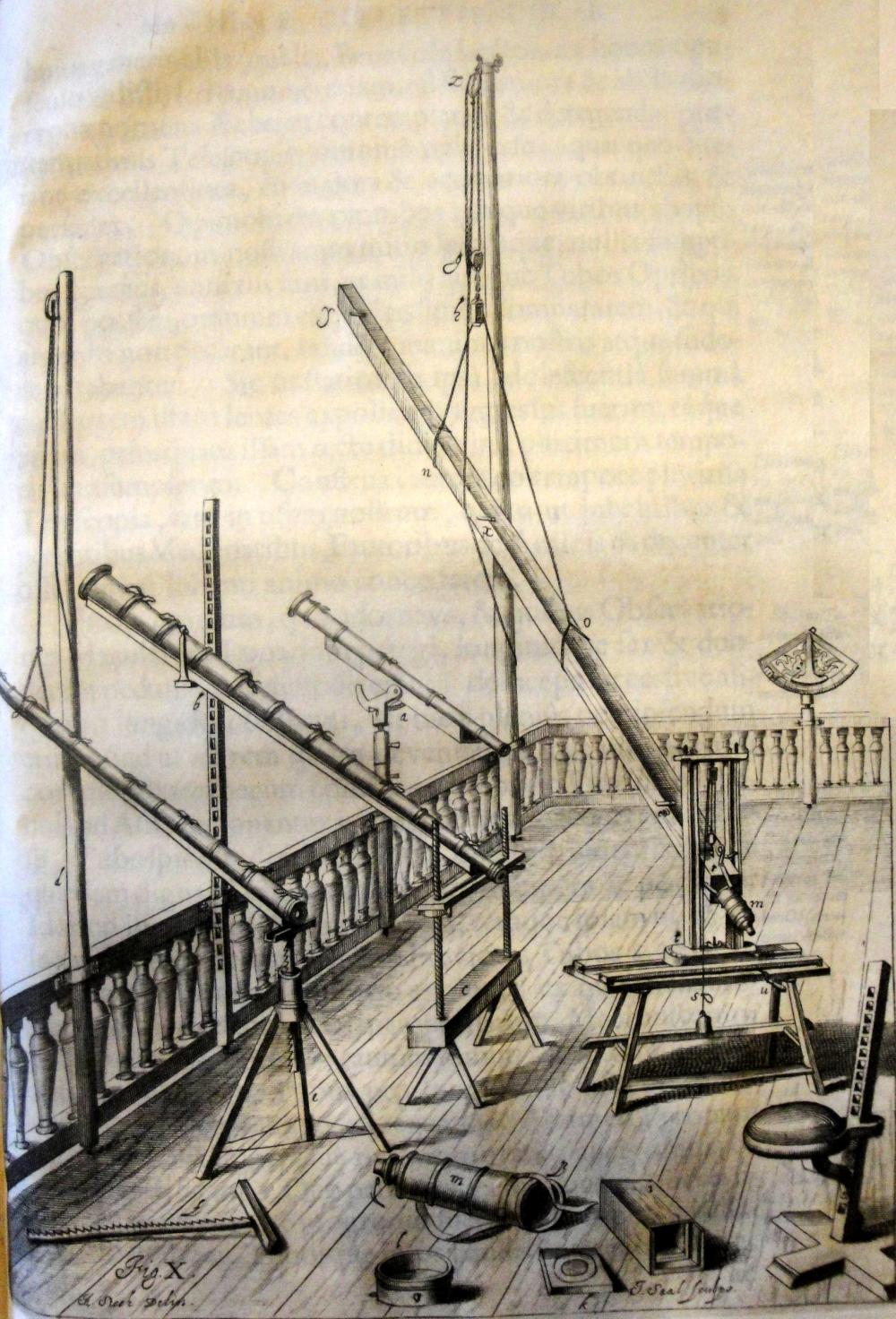

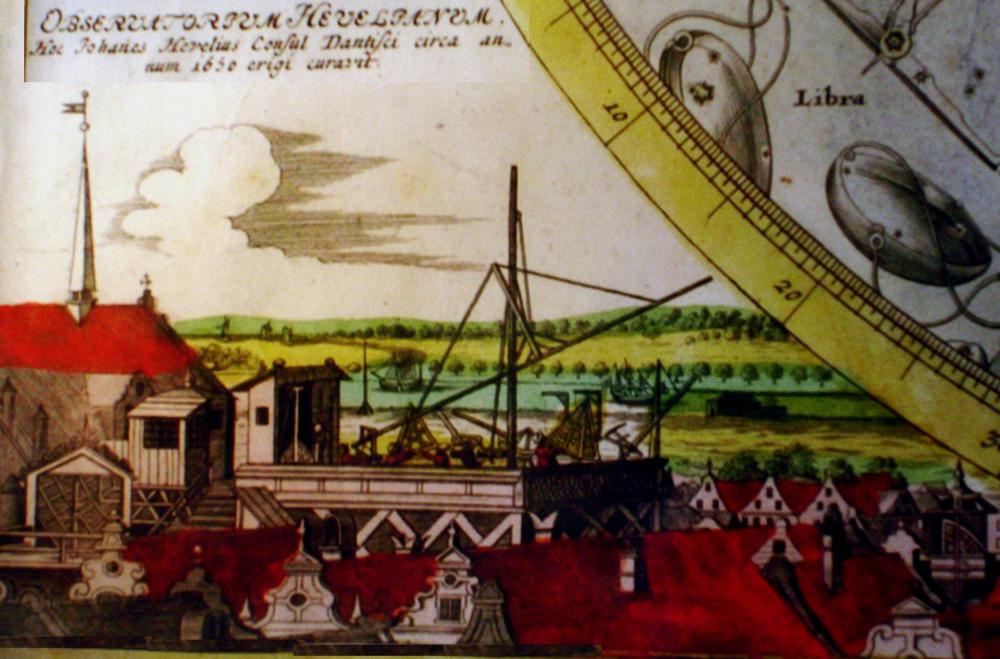

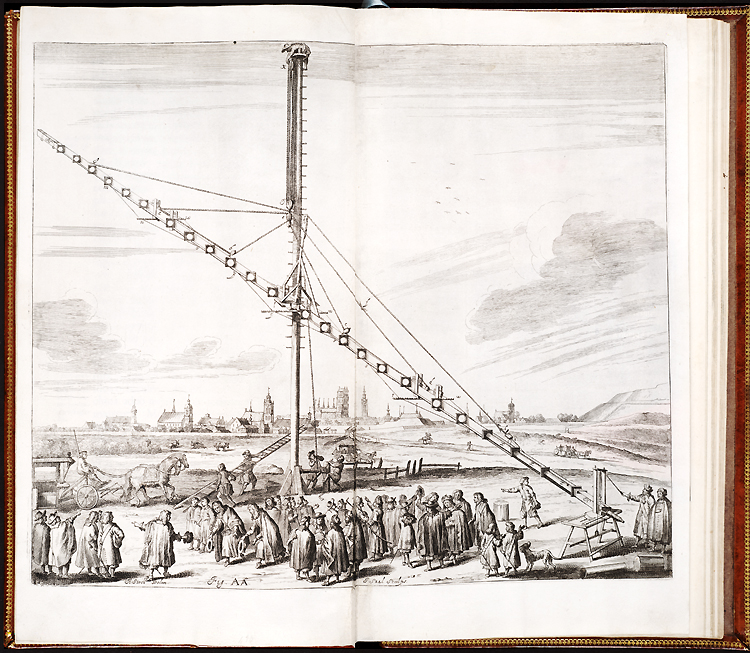

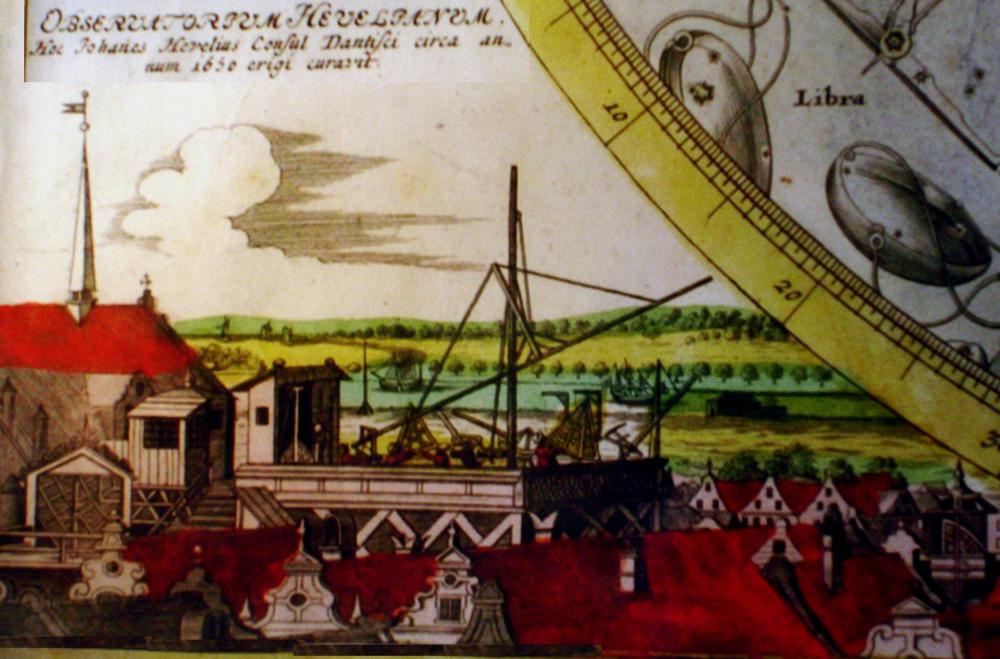

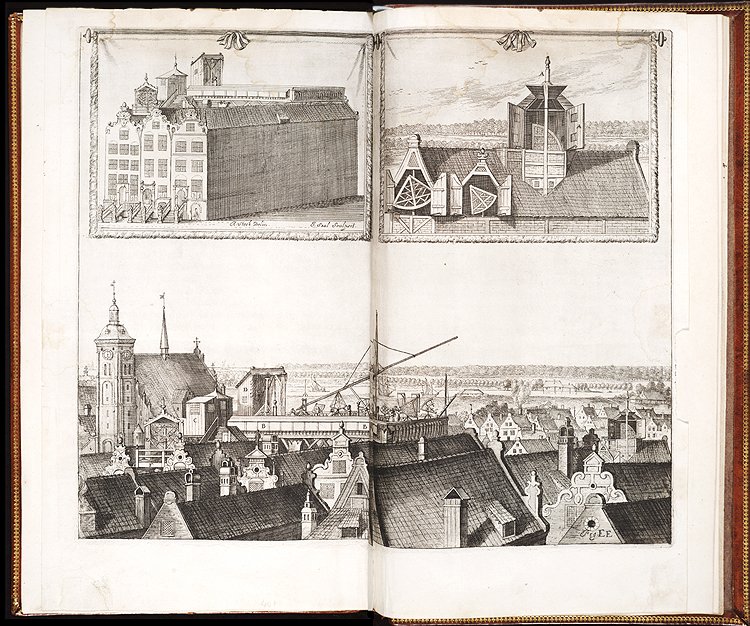

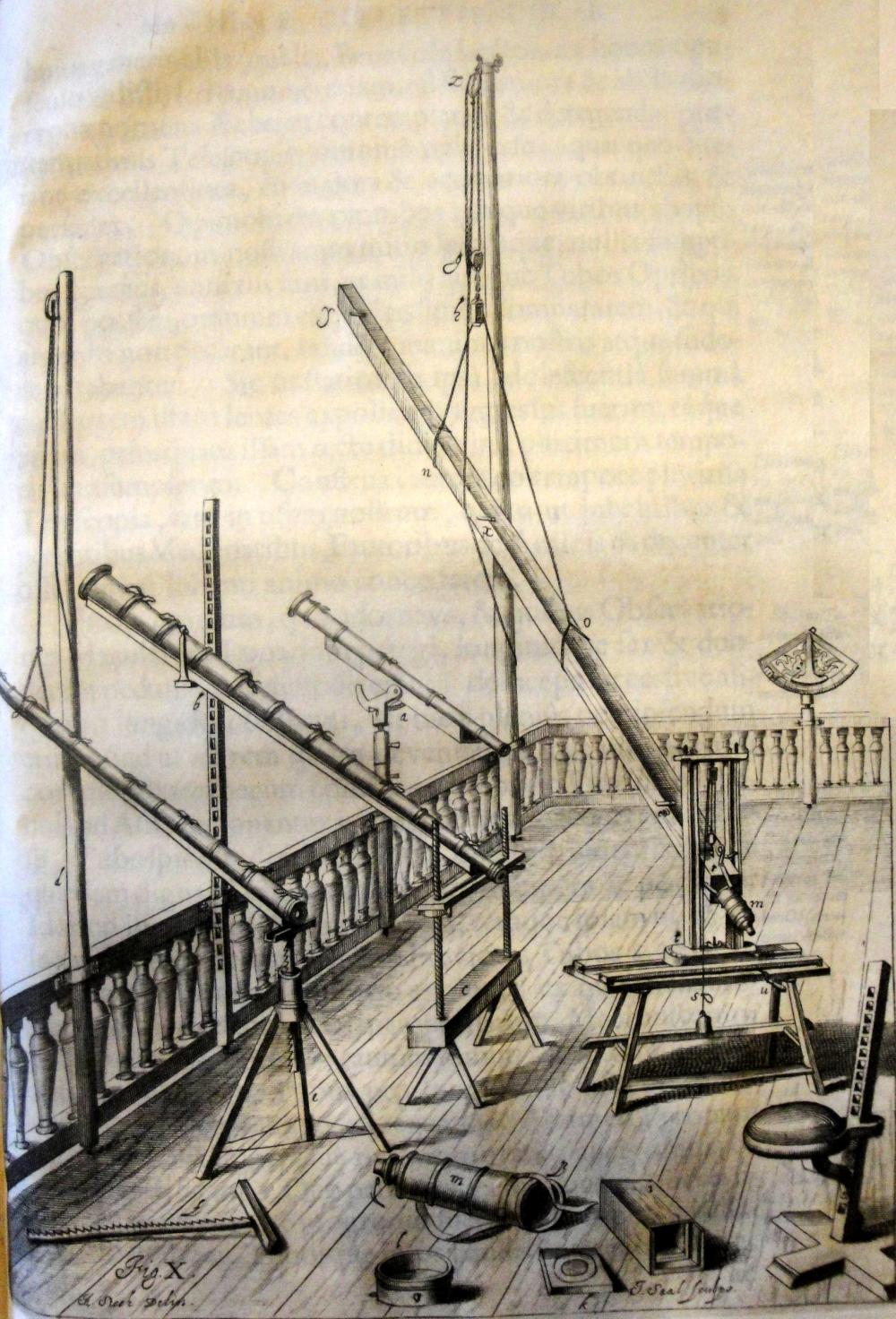

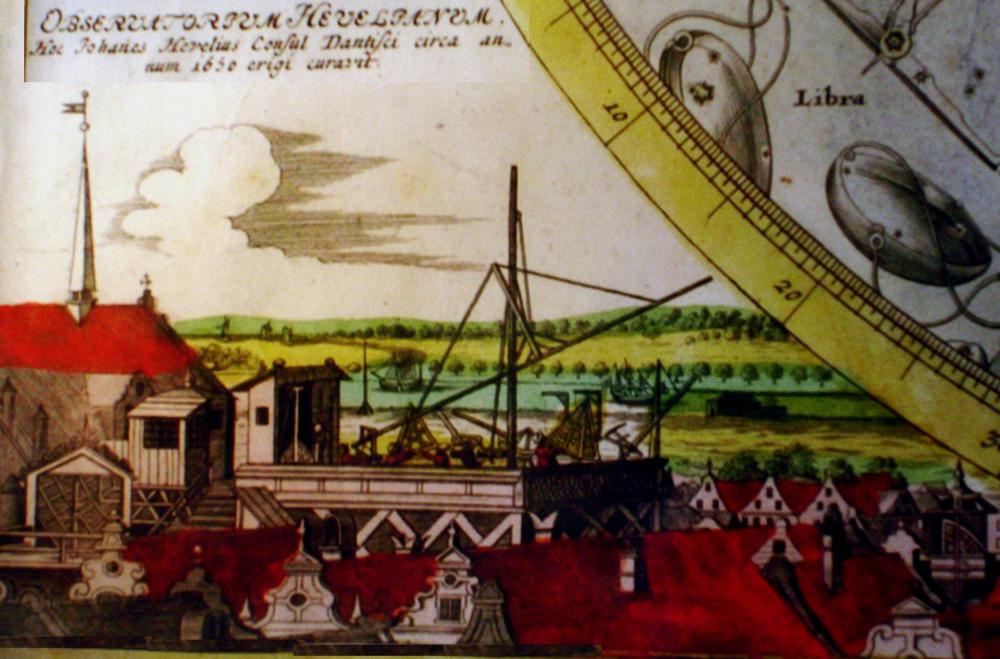

The second observatory was built around 1650. Hevelius erected a 25-by-50-foot wooden platform above the roofs of three adjacent burger houses of equal height. The drawing of J. Saal, engraved by Andrzej Stech, in "Machina Coelestis" (1673) shows Hevelius’ observatory very well.

- Looking at the buildings in the foreground on the left side there was a rotatable shelter, lower than platform; there his brass horizontal quadrant for meridian observations oriented in north-south direction was placed.

- Also for the large metal sextant and the metal octant a hut was built. It was standing on top of the north side of the main platform and it was also rotatable on wheels. In addition, it could be darkened and then used for solar observations.

- Finally, there was a third hut. There was for example a pallet for taking a rest, and in order to make it comfortable and pleasant for observers if waiting was necessary. In addition, devices, accessories and clocks were kept there.

Hevelius’ Stellaburgum, as he called his observatory, was probably also the first observatory with telescopes. This was the main purpose of the large platform that telescopes up to a length of about 50 foot could be handled.

It was very convinient that the observatory was at his home and not very far from his brewery or his workplace in the town hall as a mayor of Danzig; thus he was able to save a lot of time. Also inside of the observatory everything was quickly accessible from the living quarters, all the instruments, the library, the copper engraver workshop, the printing office.

Hevelius’ third observatory (after 1679)

In 1679 a great fire destroyed the observatory, in addition many instruments and manuscripts, prepared for printing as he reported in "Annus Climactericus" (1685). After the great fire, he decided immediately to reconstruct it and he erected a third observatory in 1681, just two years after the devastating fire. He started observing in 1682 but with very simple instrumentation.

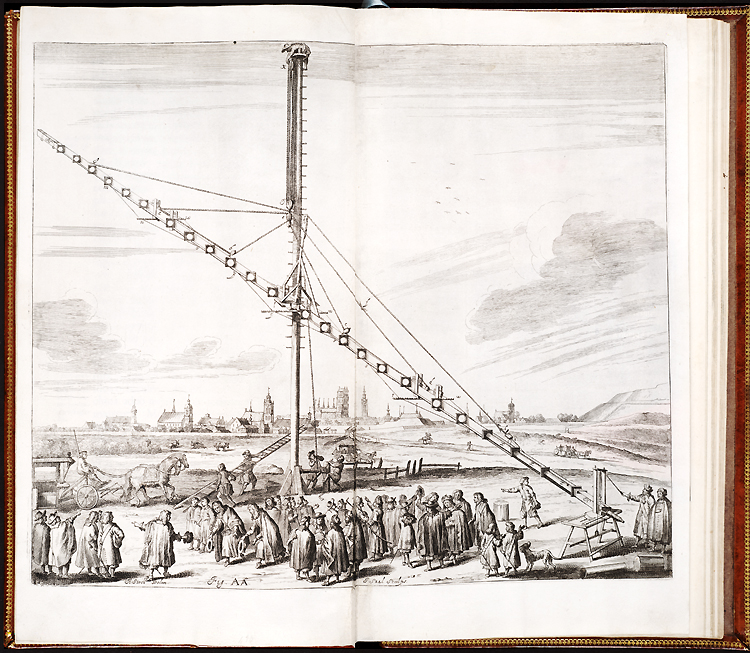

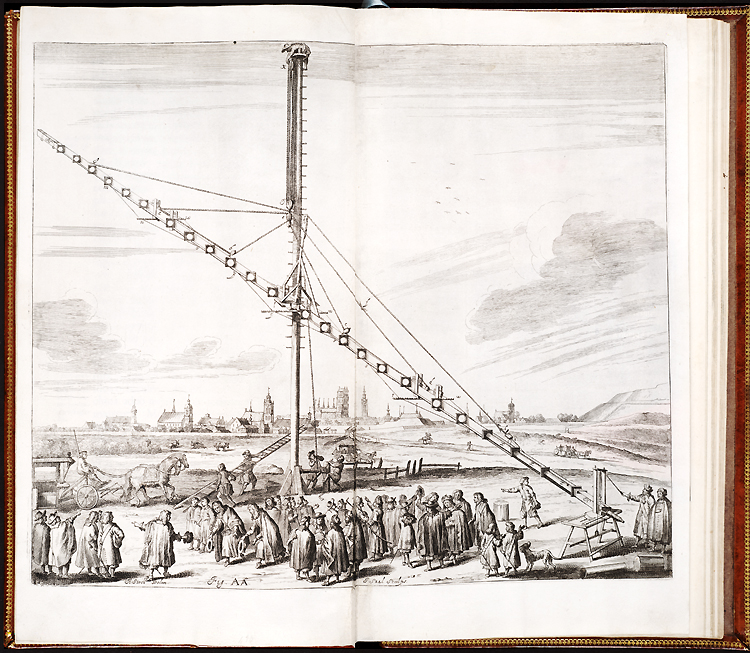

Hevelius’ observing post outside of Danzig

The observing post for his giant telescope of 140 foot was only 1.5 km air-line distance from Hevelius’ Stellaburgum observatory in the city. Kampa (2018) could find out that the place was not at the hill near his garden in Oliva Road but it was in the street "Jana z Kolna" (coordinates of about 54°22’04’’ N and 18°38’17’’ E) near the Gdańsk Shipyard, about 400m north of the pedestrian bridge to the (later) railway station Gdańsk Stocznia. There he used occasionally his largest telescope of 140 foot.

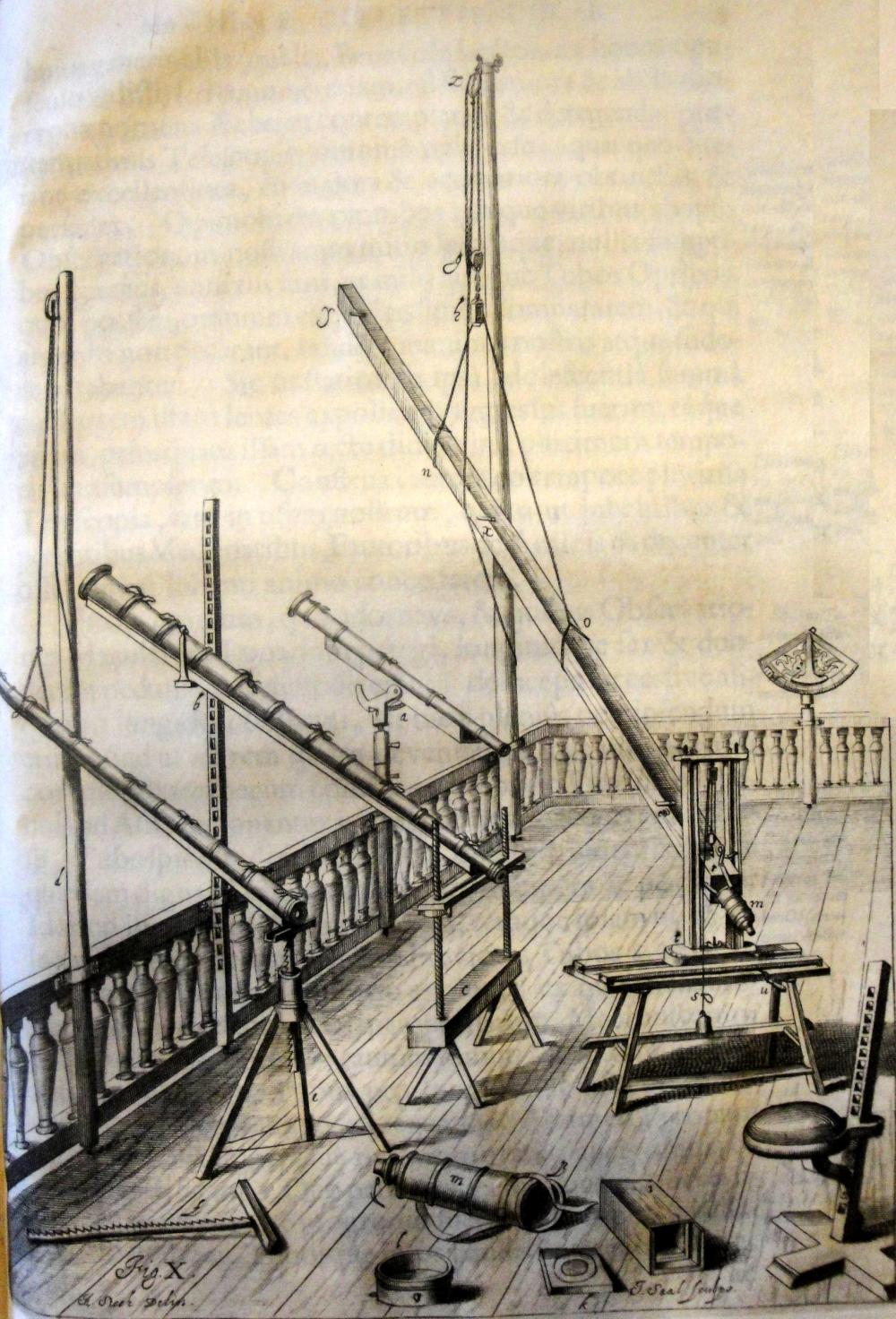

Fig. 5. Hevelius observing post for his giant telescope of 140 foot outside of Danzig (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

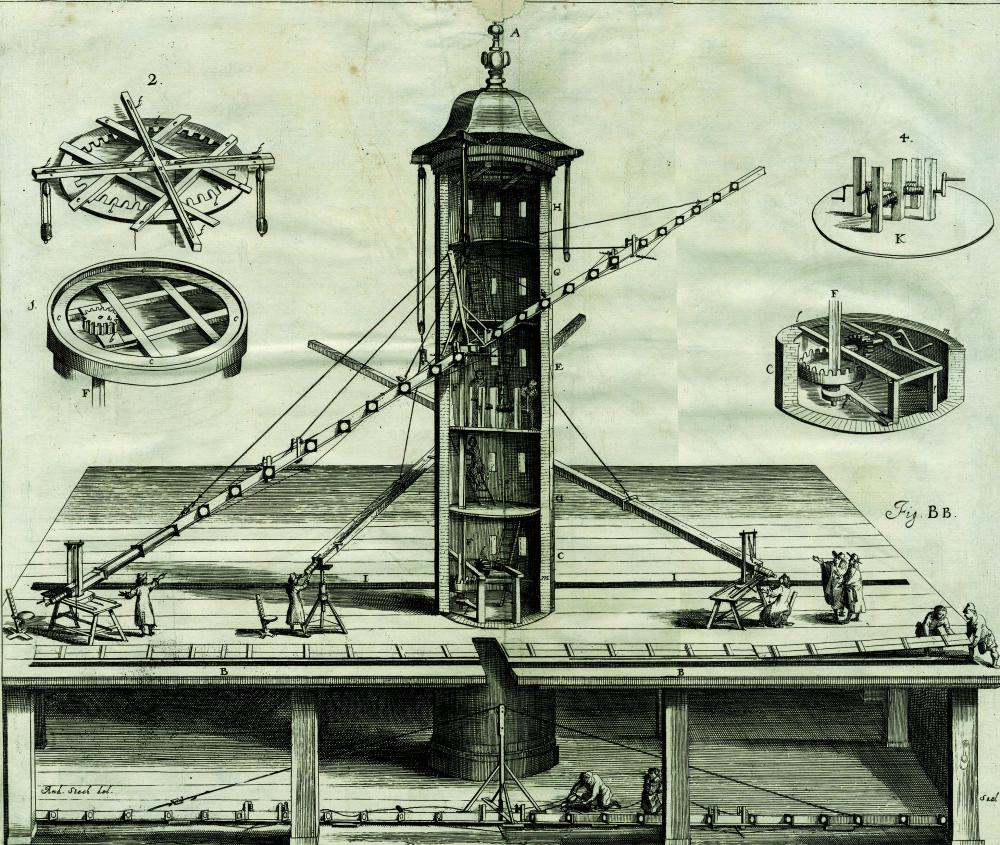

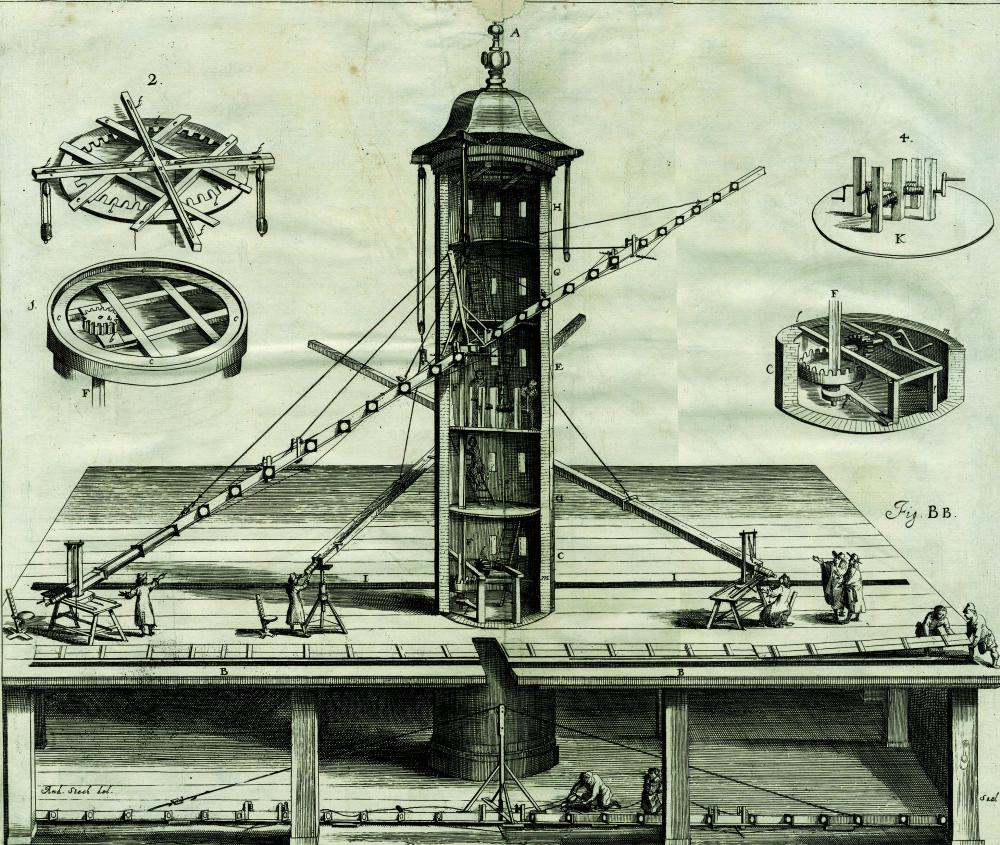

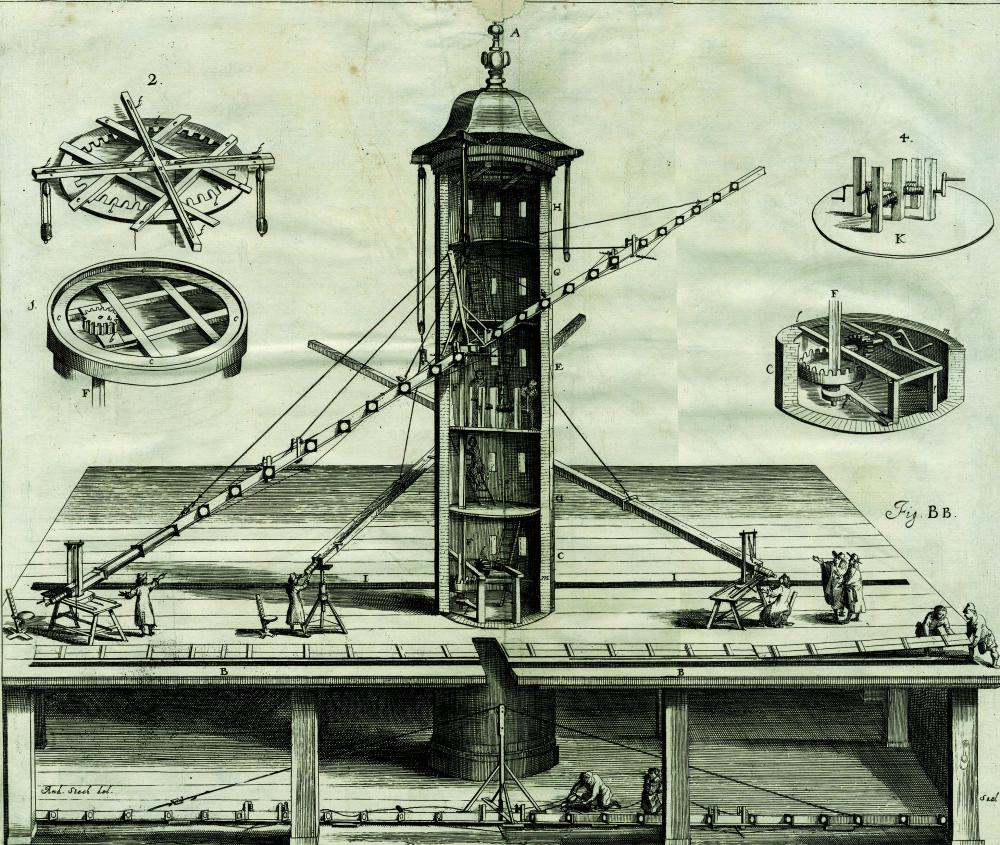

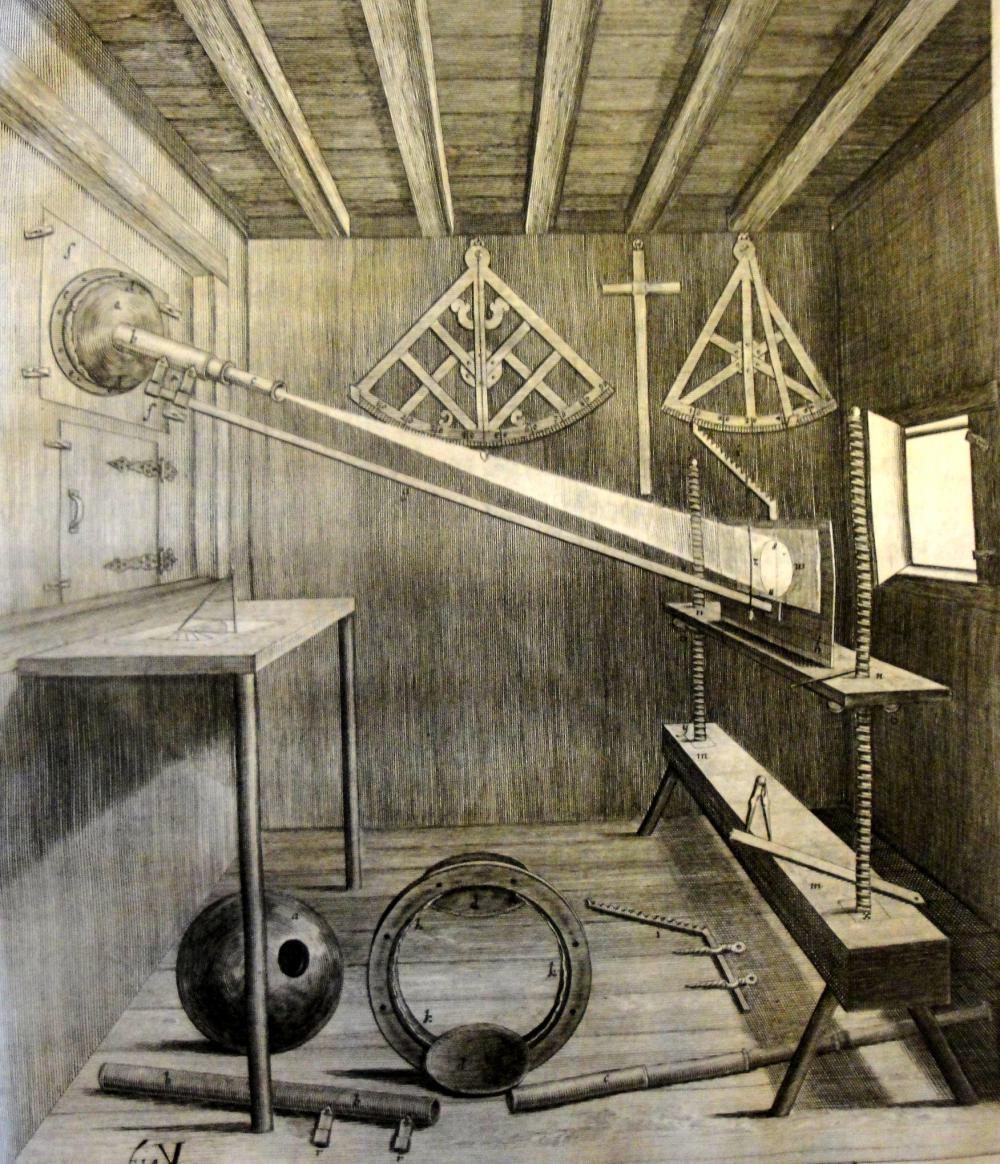

Design for a first observatory for using telescopes

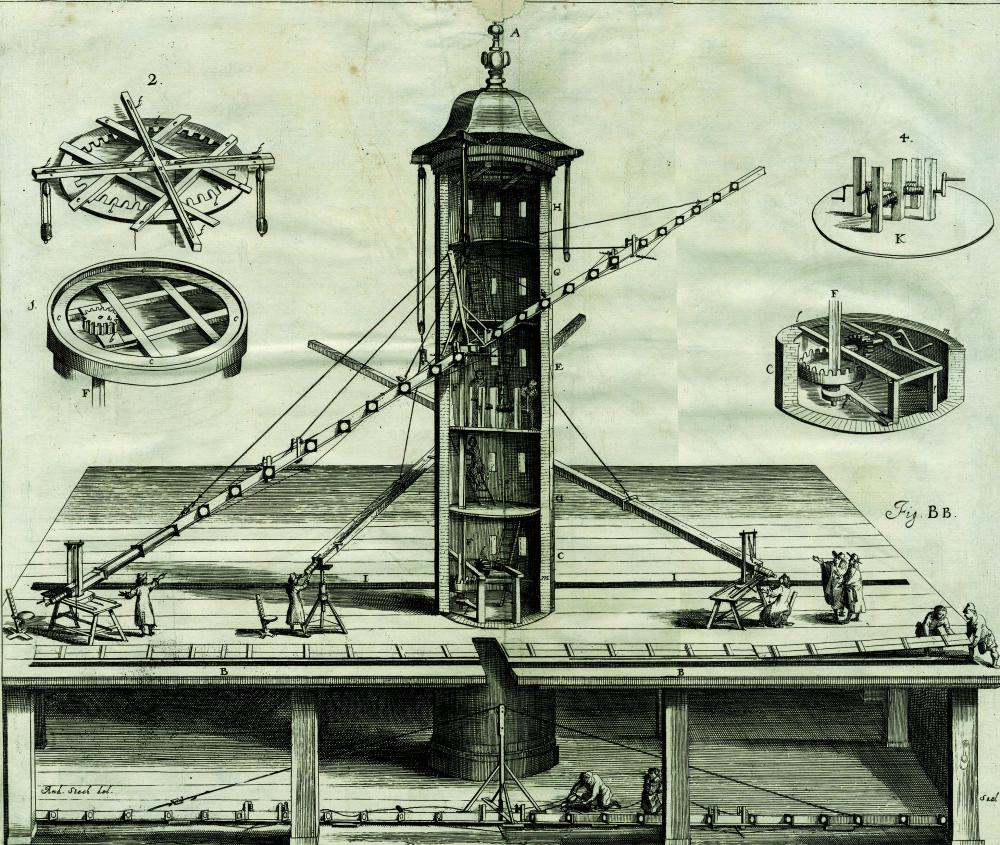

Because observing with his largest telescope of 140 foot was not at all comfortable, he designed a new perfect telescope observatory in order to handle the long tubes. For the planned 150 foot telescope the tower which he used as mounting had to be about 100 to 120 foot high. The cross-section of his circular observatory should have a diameter of 12 to 15 foot. But due to his age he never succeeded to realize his dream.

Fig. 6. Hevelius design for a first observatory for using telescopes (Machina Coelestis, 1673), (Hamburg Observatory)

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 11

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:36:40

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

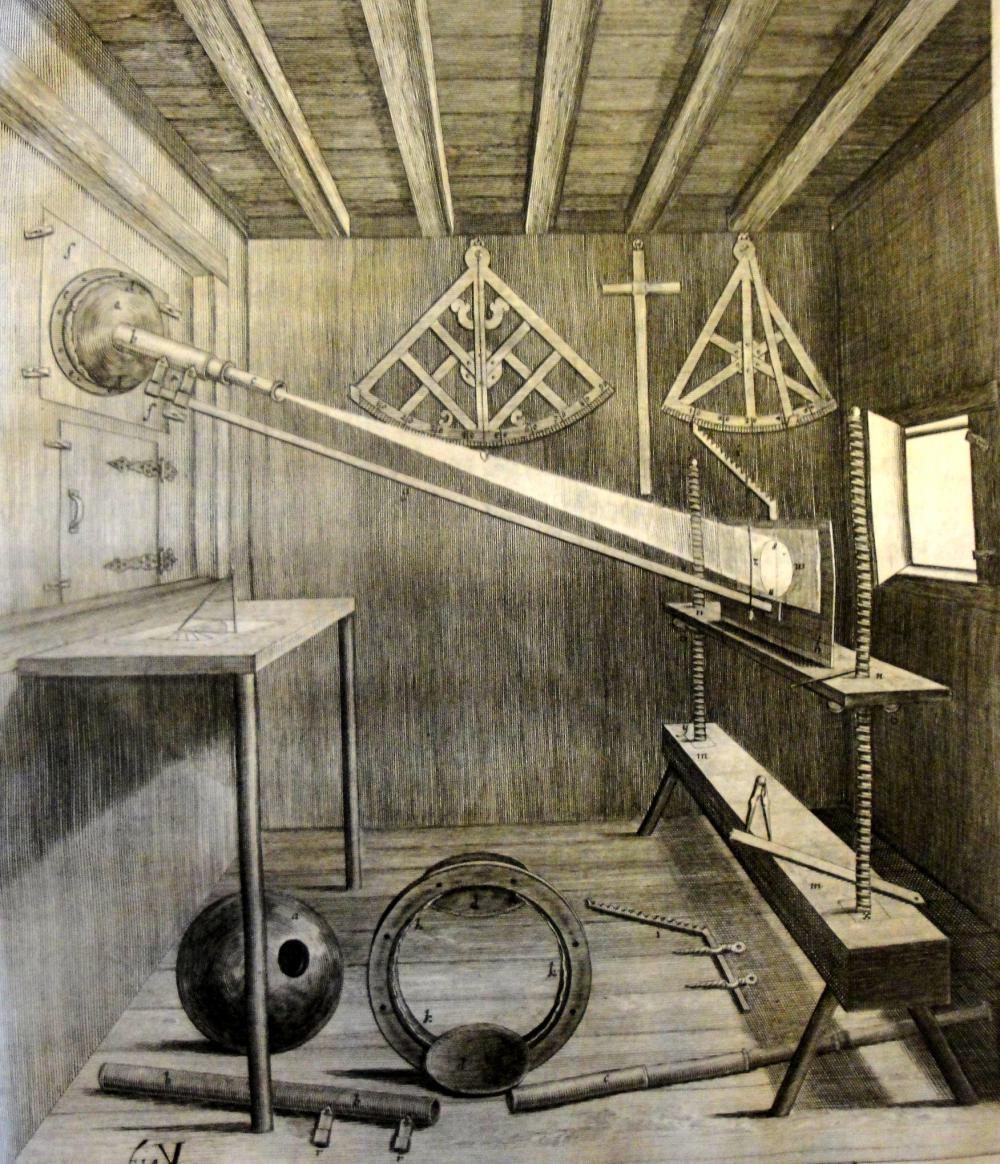

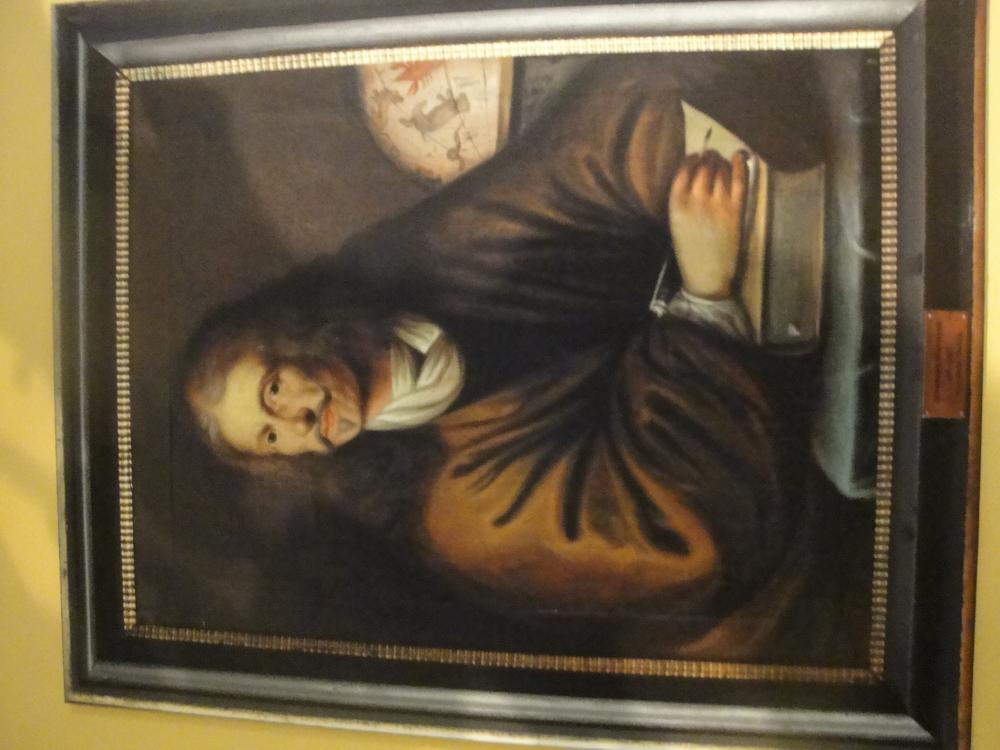

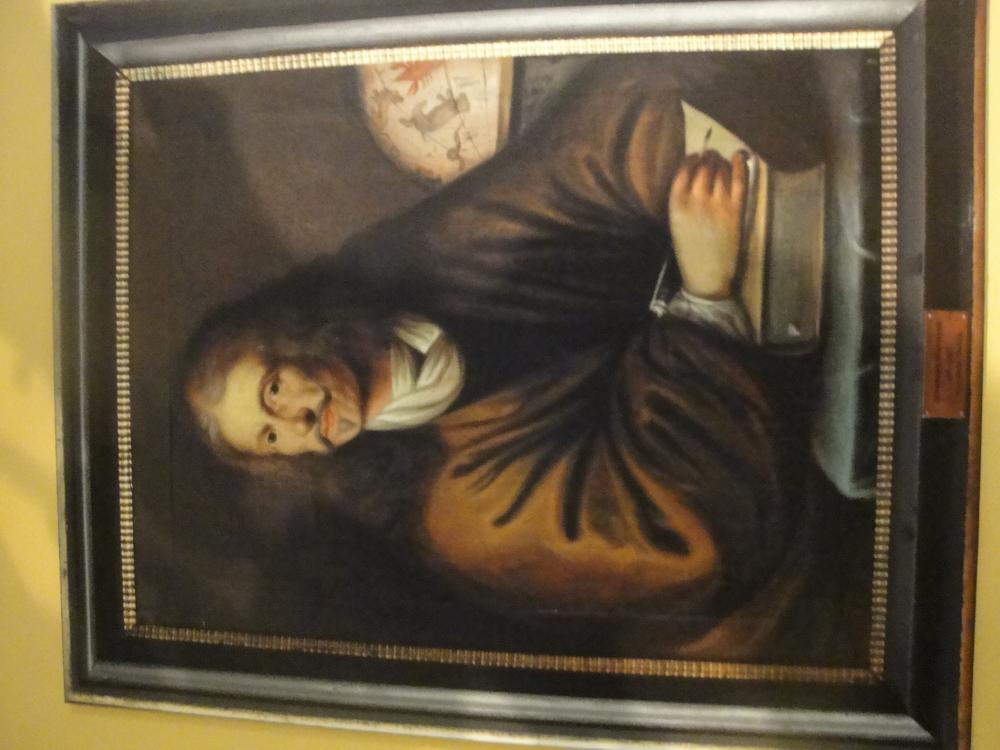

Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687), brewer, mayor an astronomer, is famous for his outstanding astronomical instruments and his observatories of the 17th century. The observatory was erected on the roofs of his three houses in Danzig (Gdańsk). Most of his instruments Hevelius described in his "Machina Coelestis" (1673). Hevelius gained international fame already for his studies of the topography of the moon surface. A very detailed study was made by Kampa (2018); this is the basis of this presentation of highlights of Hevelius scientific work and making or using instruments.

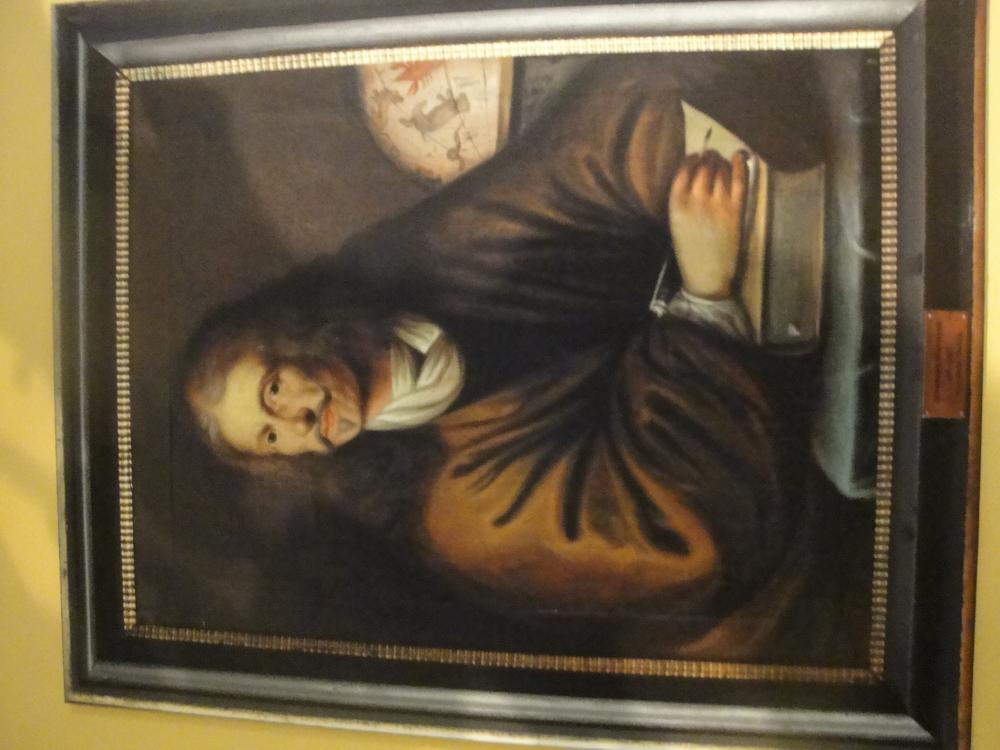

Fig. 7. Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687), portrait in Trondheim (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Hevelius constructed his long telescope tubes following the example of Robert Hooke (16351703) who had sent him a drawing and instructions. He even printed this sketch on the frontispiece of his "Cometographia" (1668).

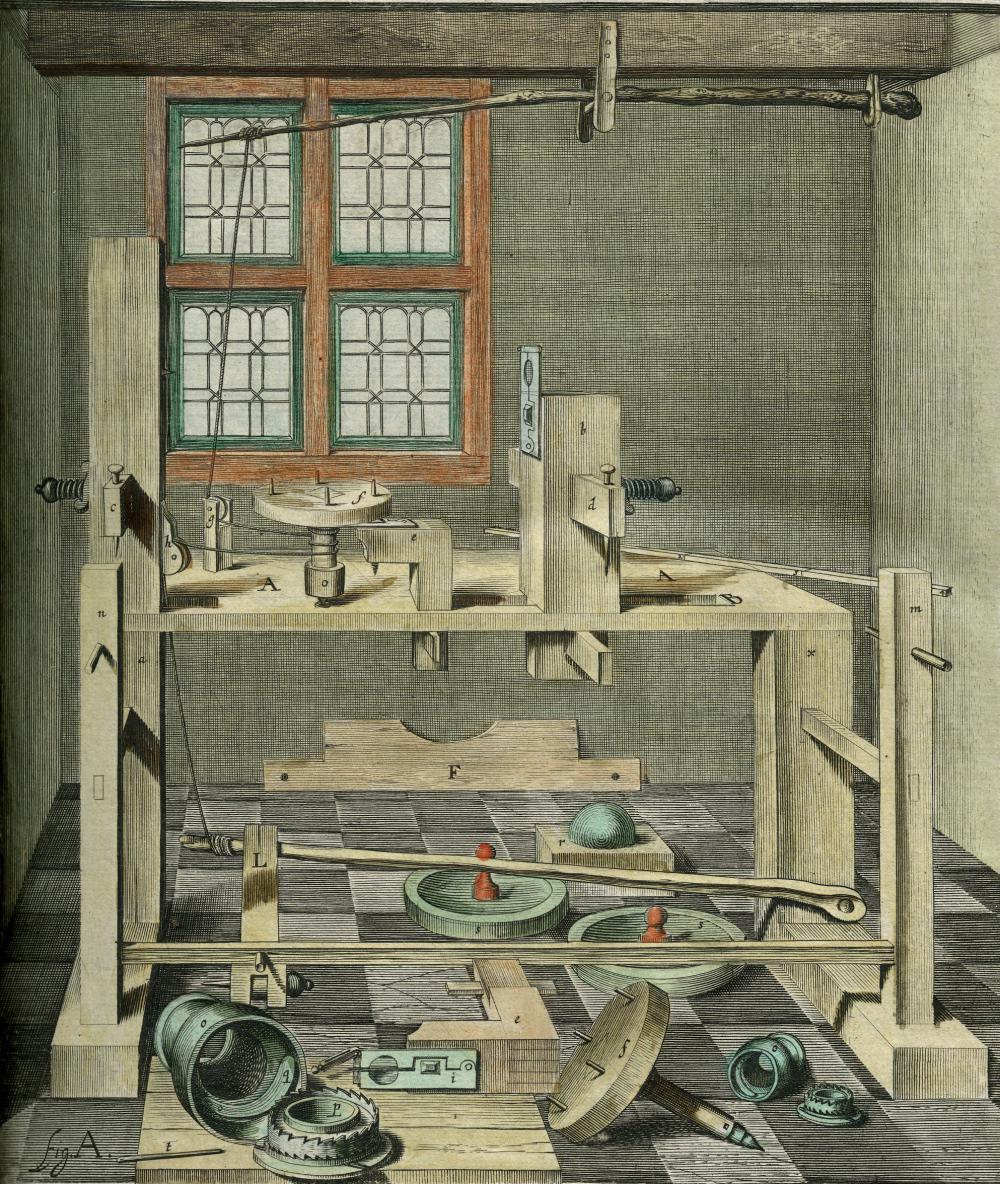

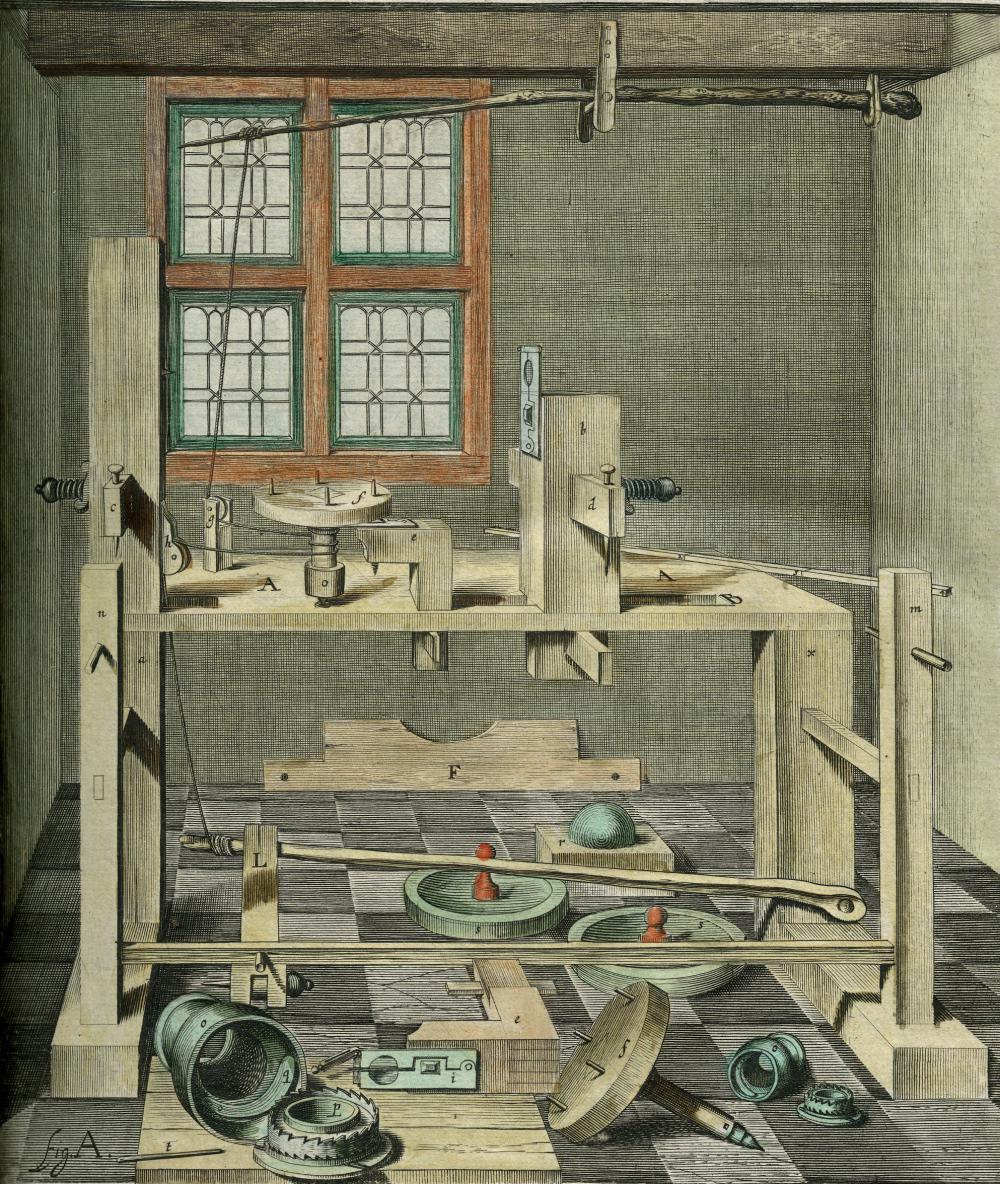

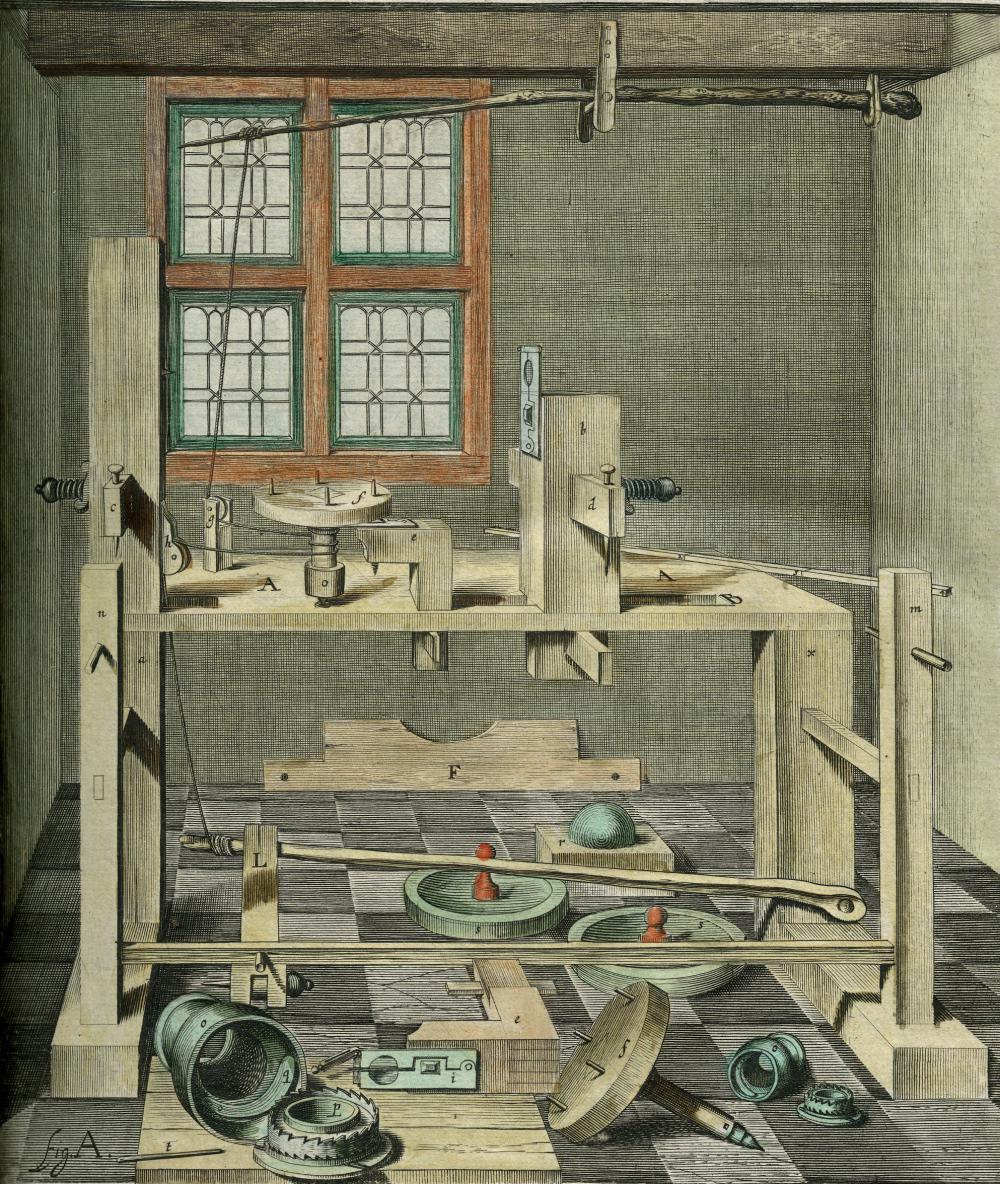

At the beginning of his career Hevelius experienced lens grinding and even tried to build a grinding machine for hyperbolic lenses. But later due to the lack of time he did no longer grind the lenses by himself. He bought most of his lenses from foreign opticians, e.g. Johann Wiesel (1617--1681) of Augsburg, Tito Livio Burattini (1617--1681) of Warsaw, Christopher Cock (~1660--1696) of London. Hevelius used telescopes with focal lengths 6 ft, 12 ft, 20 ft and 50 ft. Neither the 70 foot nor the 140 foot telescope, which Hevelius described in his "Machina Coelestis" (1673), were ever used for observations (Kampa 2018). The tube for the giant telescope, which Hevelius had build, before he received the lens, turned out to be too short. So Hevelius had no pioneering role regarding the evolution of giant and aerial telescopes.

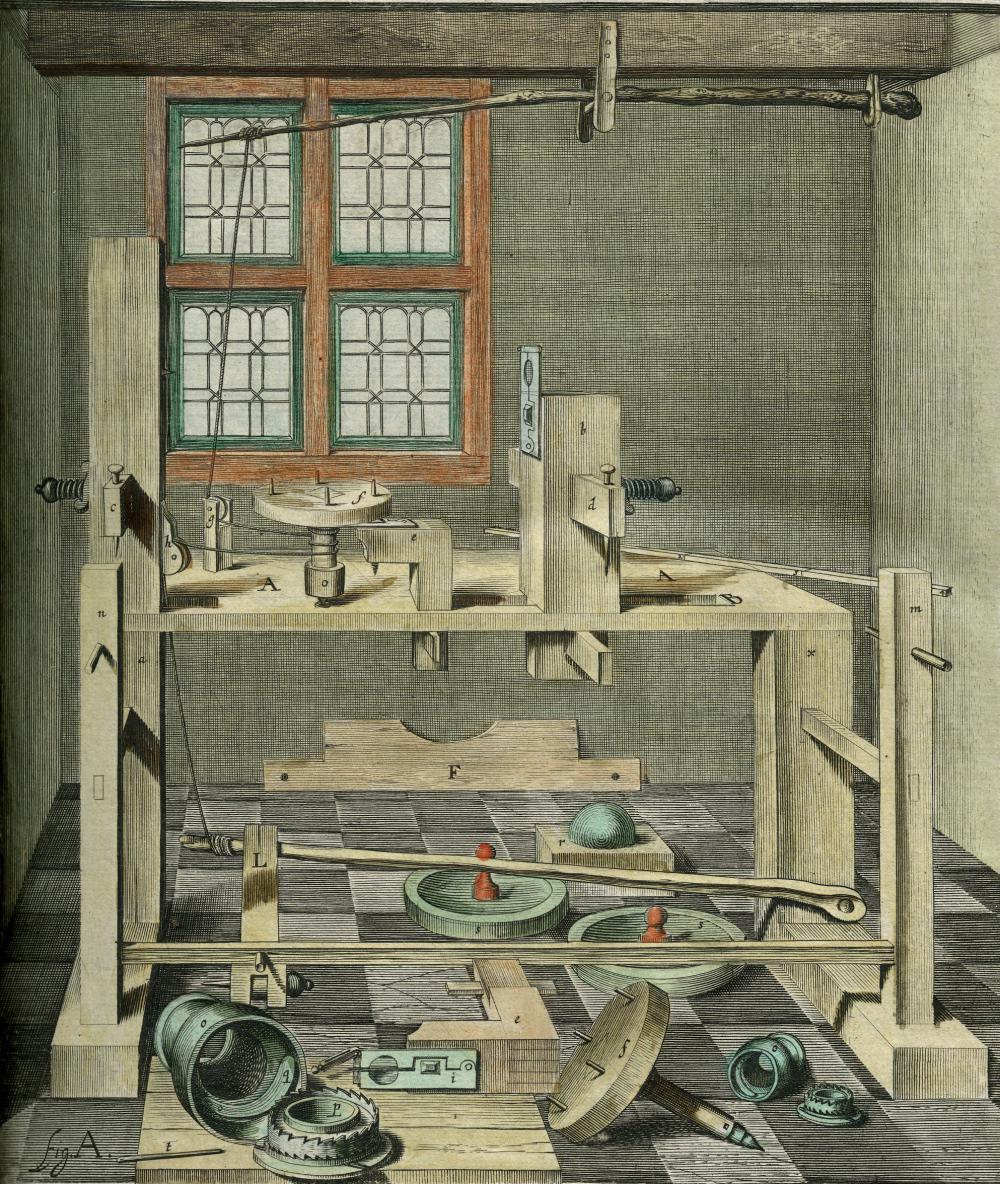

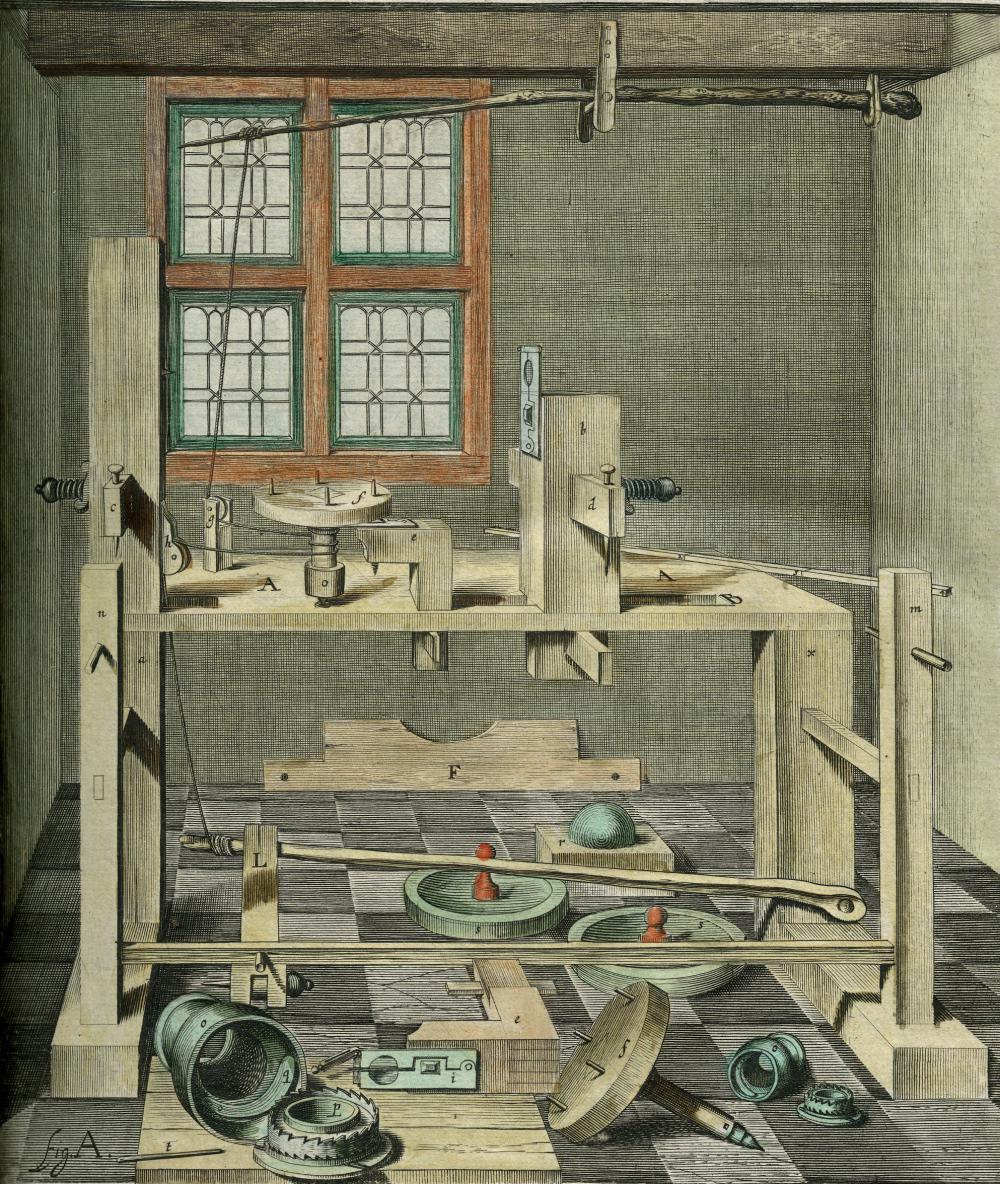

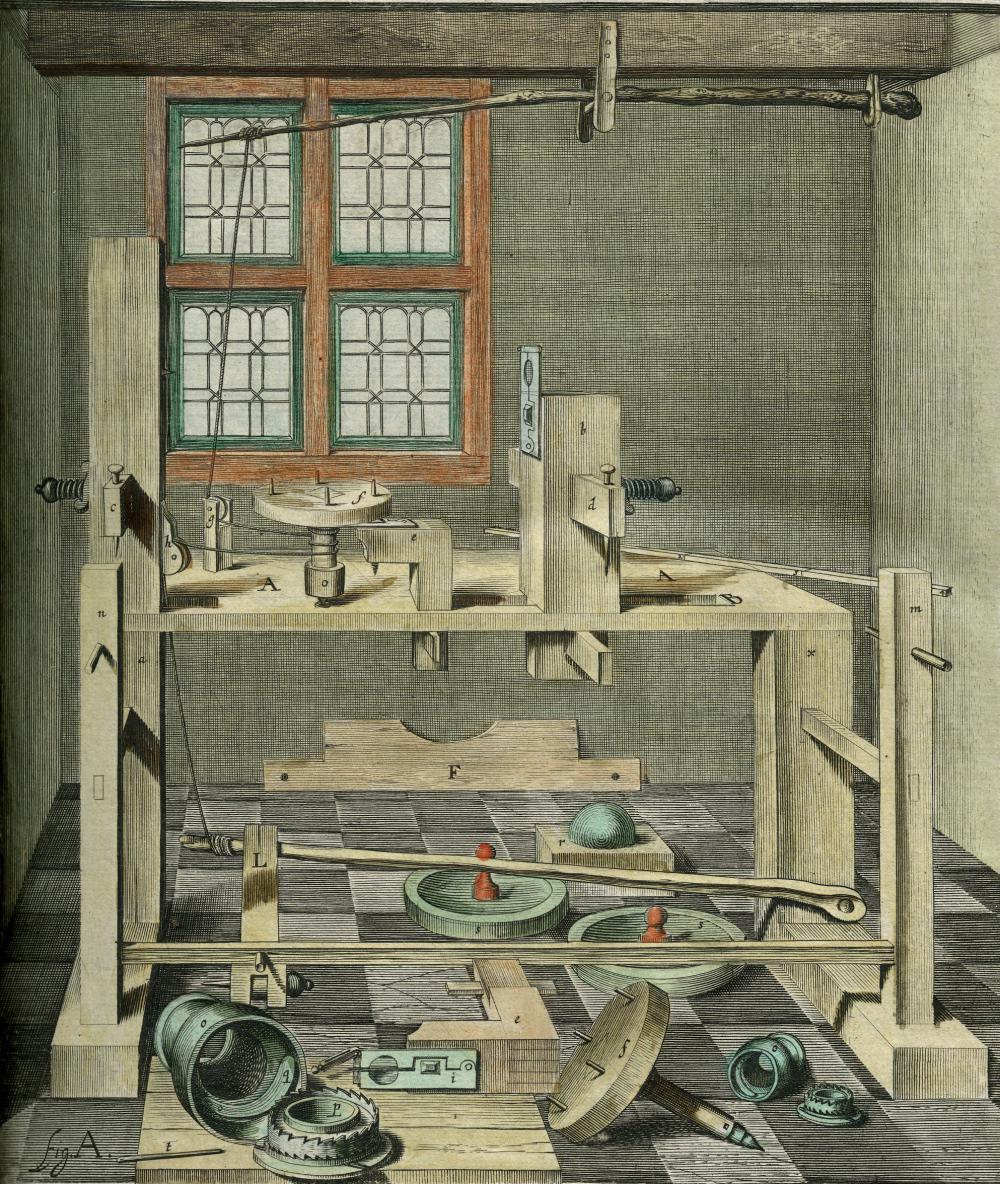

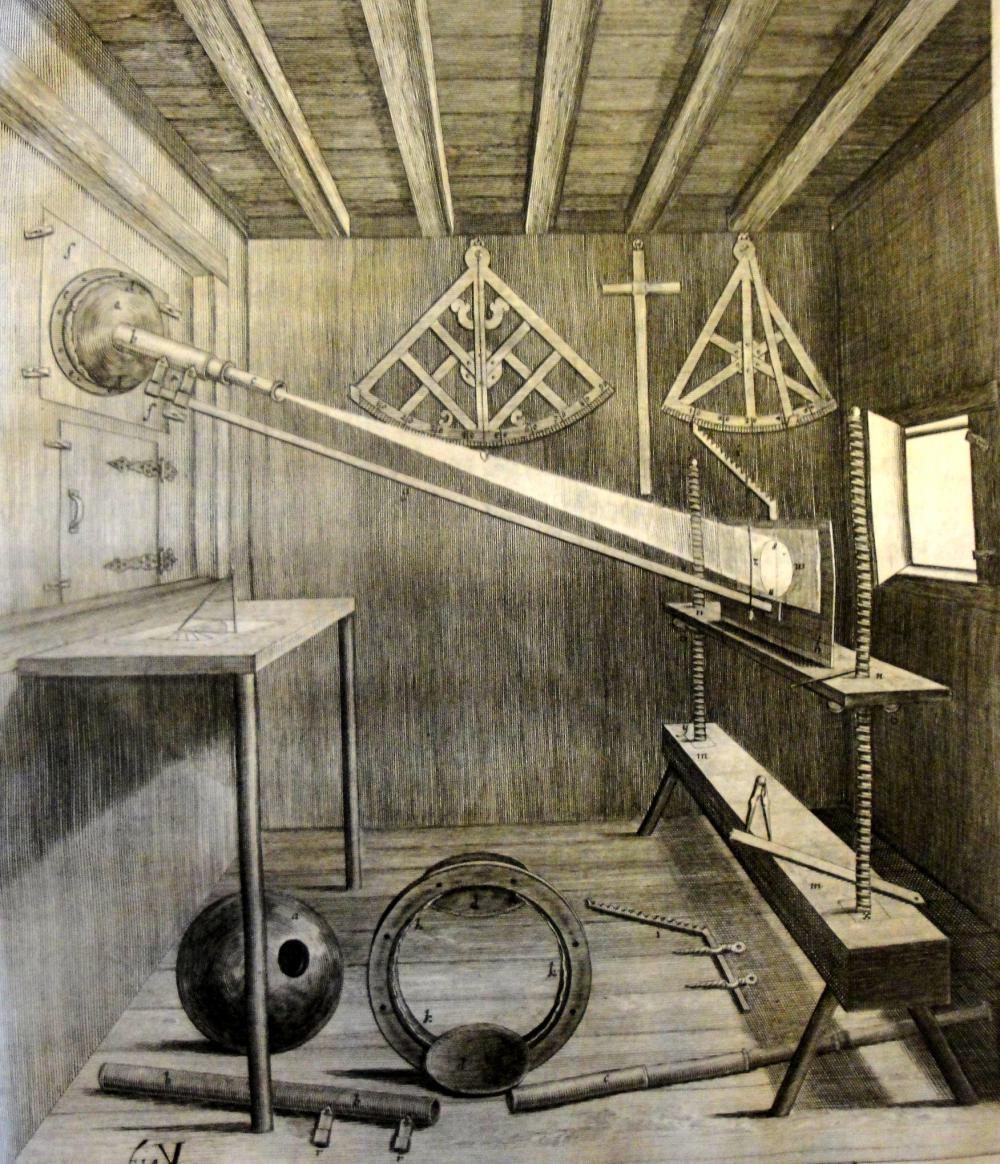

Fig. 8. Hevelius’ workshop for grinding lenses ("Machina Coelestis", 1673)

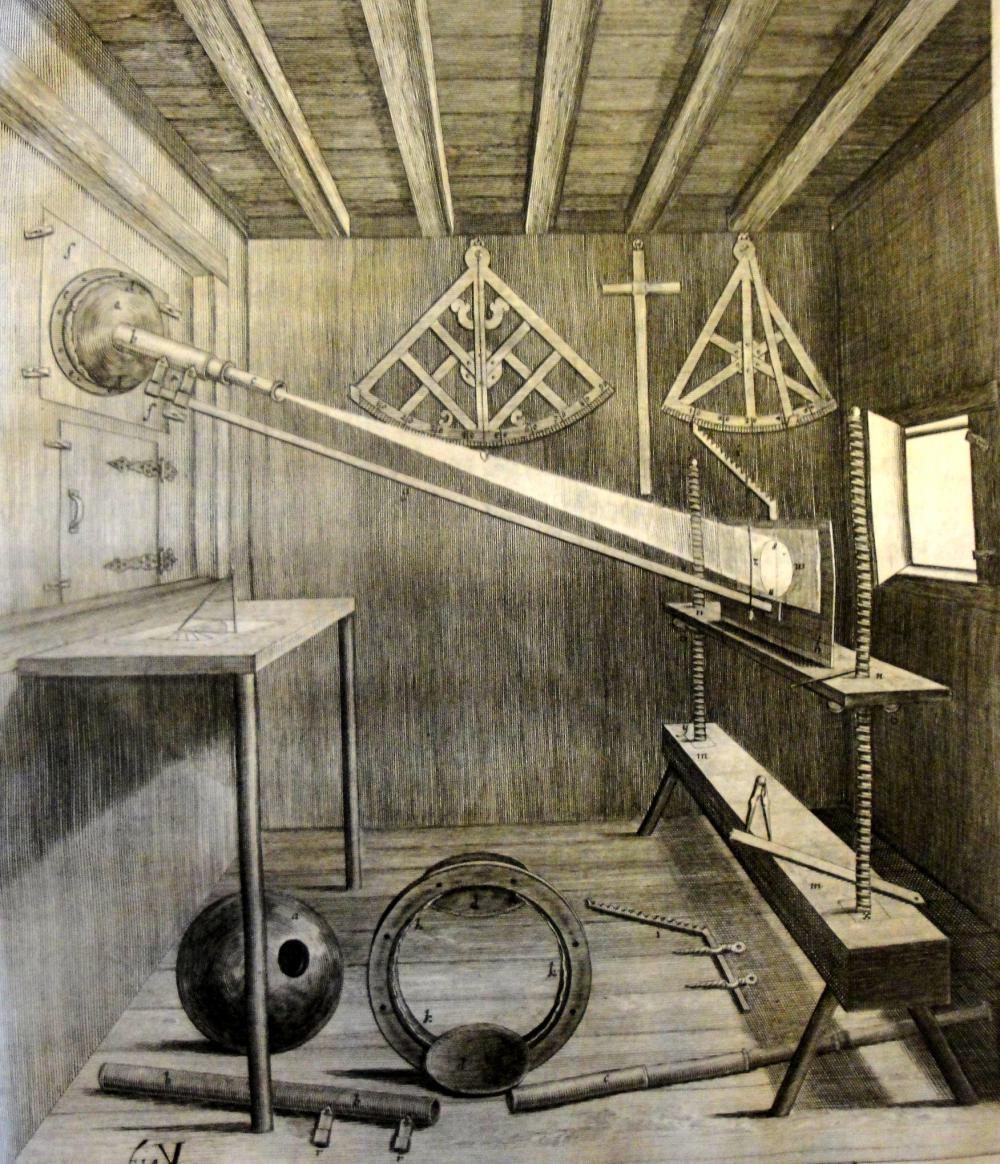

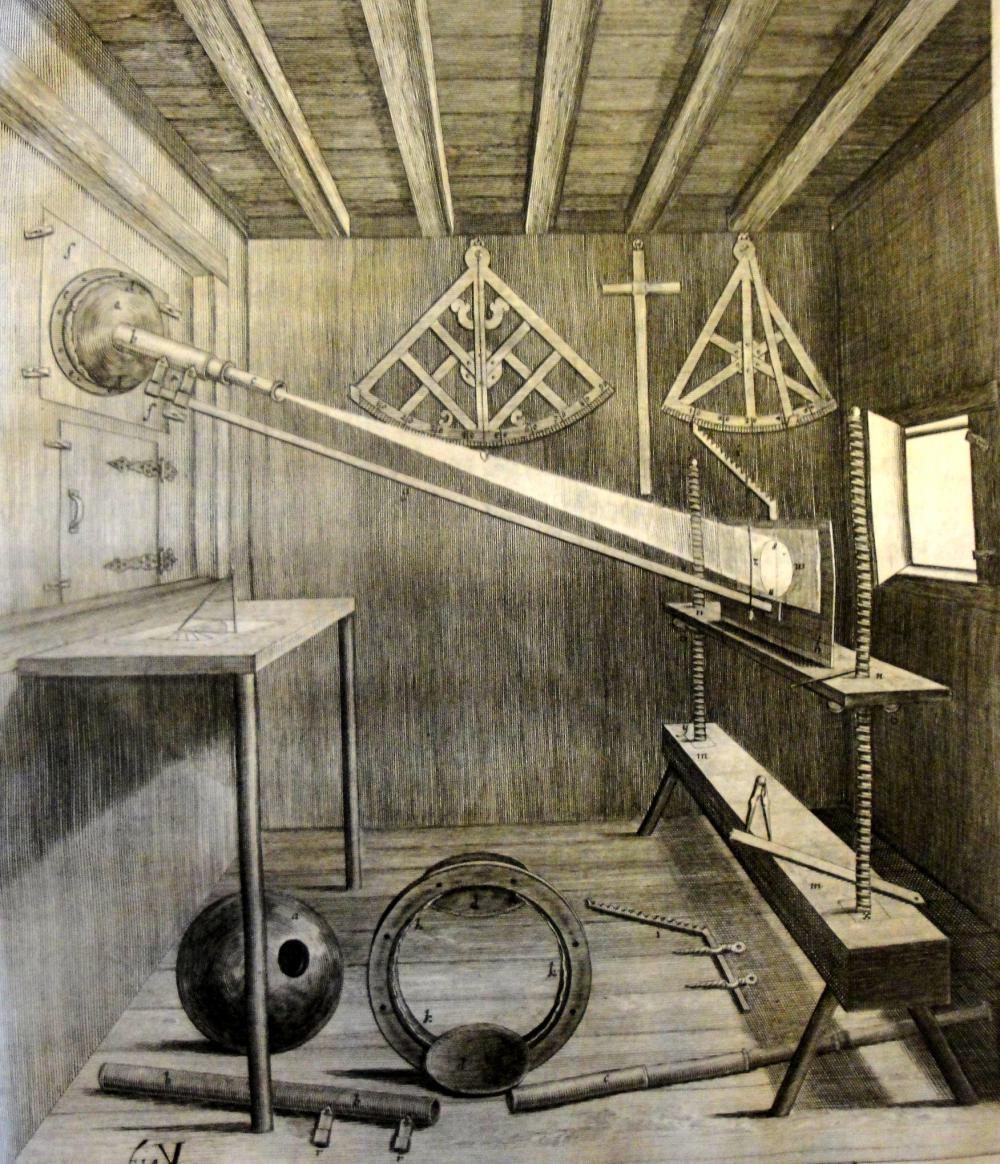

In his third observatory Hevelius started to use a micrometer inserted into a 10 foot telescope to measure small angles. But his three big angle measuring devices made of metal (the azimuthal quadrant, the sextant and the octant) were by far his most frequently used instruments.

Fig. 9. Hevelius’ workshop for grinding lenses ("Cometographia", 1647), (Hamburg Observatory)

In order to derive the coordinates of the stars Hevelius used two calculating methods. For the distance method Hevelius needed three angular distances with two reference stars. For the altitude method on the other hand the meridian altitude and only one angular distance to a reference star were sufficient. The analysis of the manuscript of the star catalogue showed that Hevelius prefered the altitude method. The distance method was used mainly for stars with high declinations.

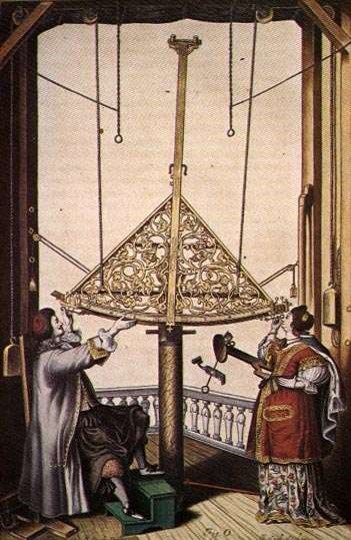

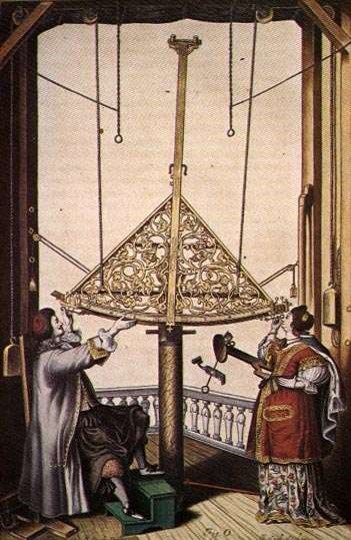

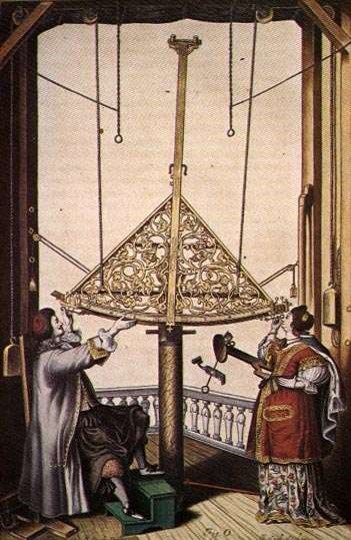

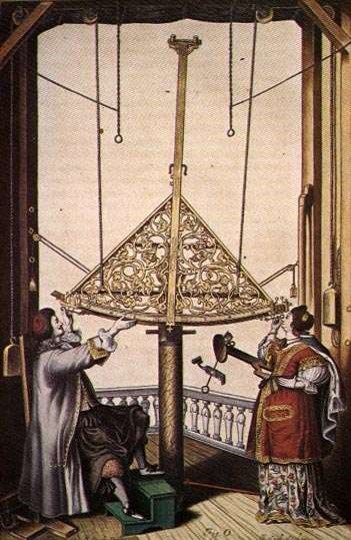

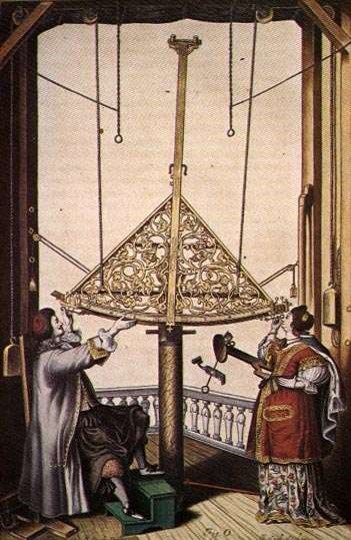

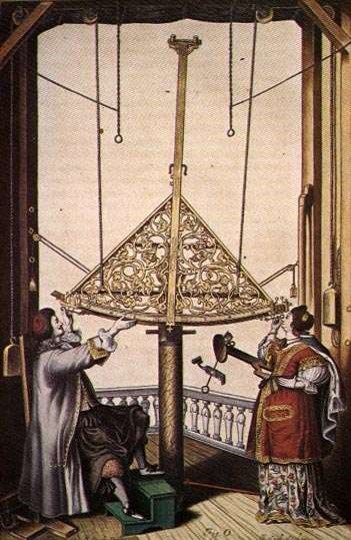

Hevelius’ first wife Catharina, born Rebeschke, (1613-1662), helped Hevelius to measure star distances. So far now only his second wife Elisabeth, born Koopman, (1647-1693), was famous for doing this. Since 1663, Elisabeth, 36 years younger, became his assistant and worked for 27 years with him. Johannes praised her as a clever co-operator in his publications. A stitch in "Machina coelestis" shows them observing together with the large sextant. In 1669 they published "Cometographia".

Fig. 10. Johannes and Elisabetha Hevelius observing (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

In 1661 Hevelius compiled a star catalogue of high accuracy "Prodromus astronomiae" (Danzig 1690) based on observations with `Tychonic’ instruments, without telescopic sights, which he built partly by himself. In 1679 Edmond Halley (1655--1742) visited Hevelius and checked the observing possibilities and results and was finally astonished that Hevelius was really able to determine stellar positions so well without a telescope.

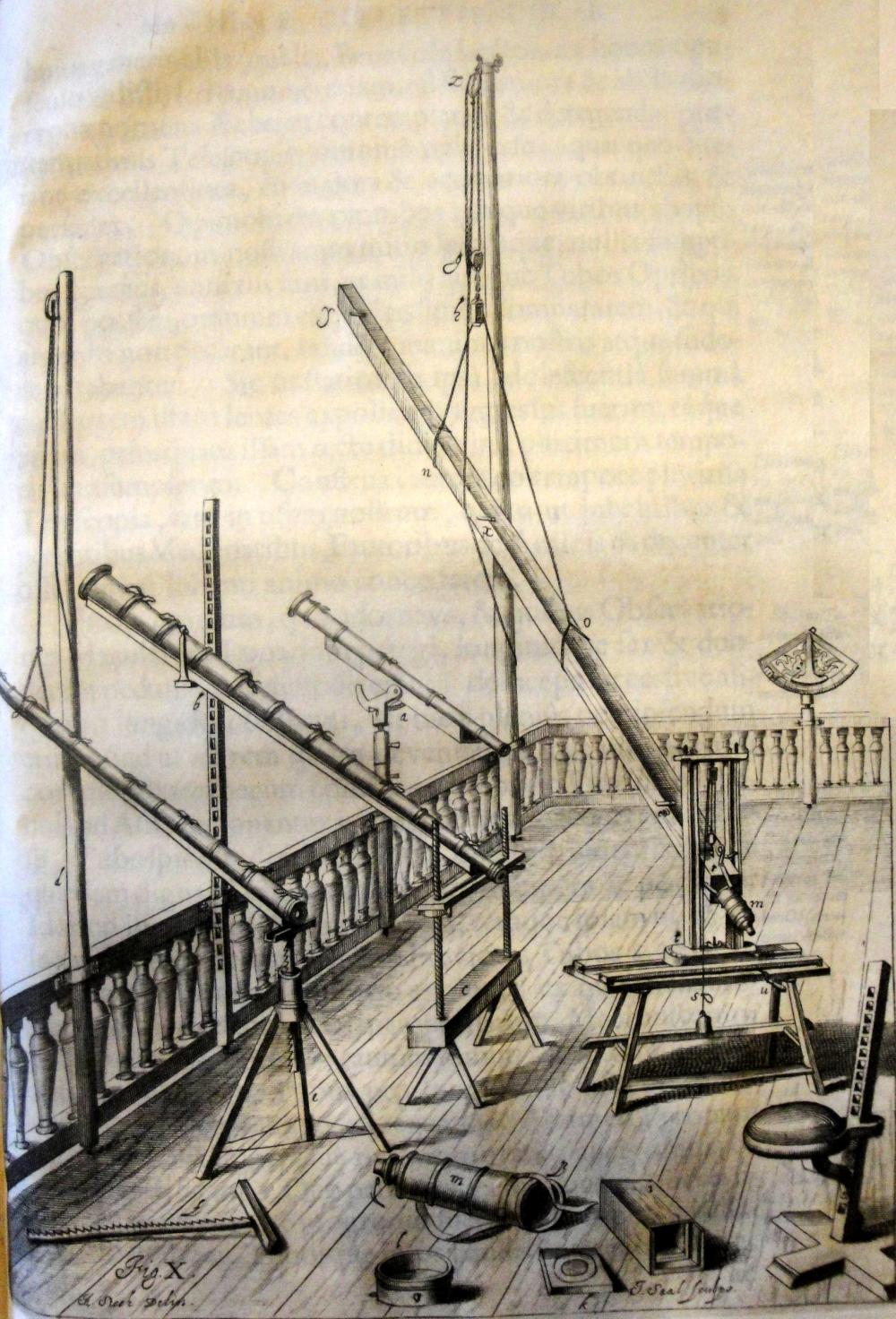

Fig. 11. Hevelius’ telescopes from 10 to 50 foot (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

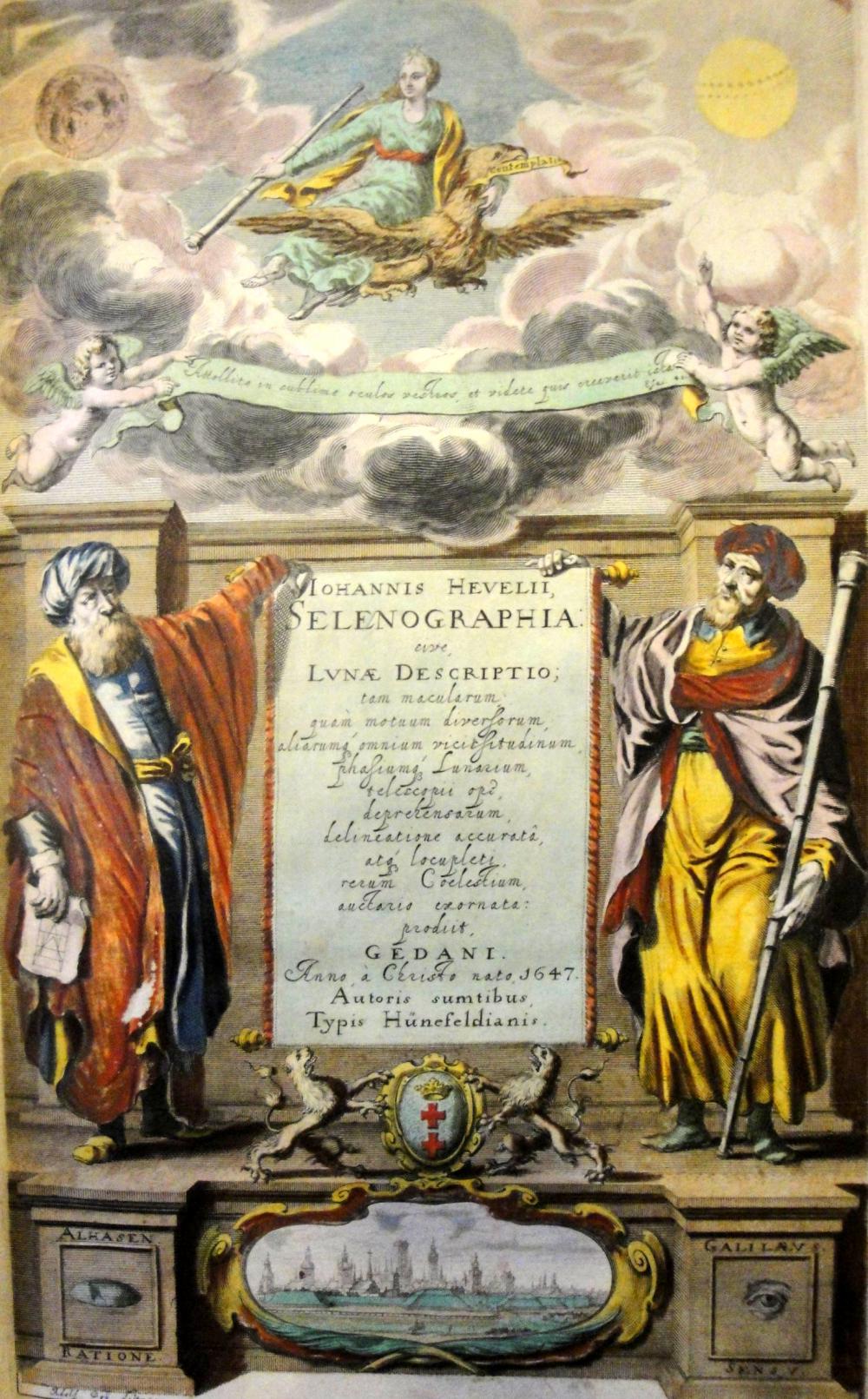

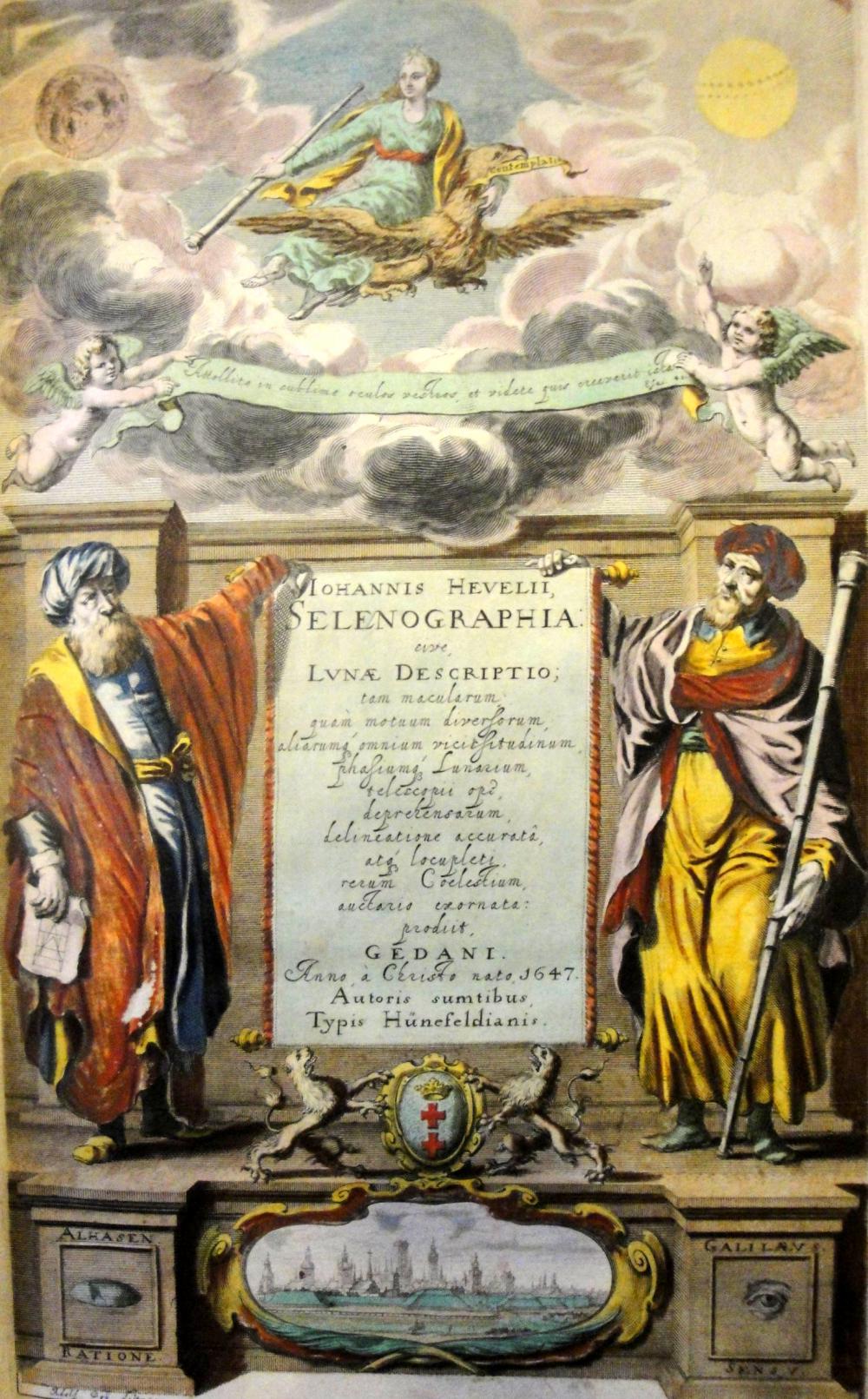

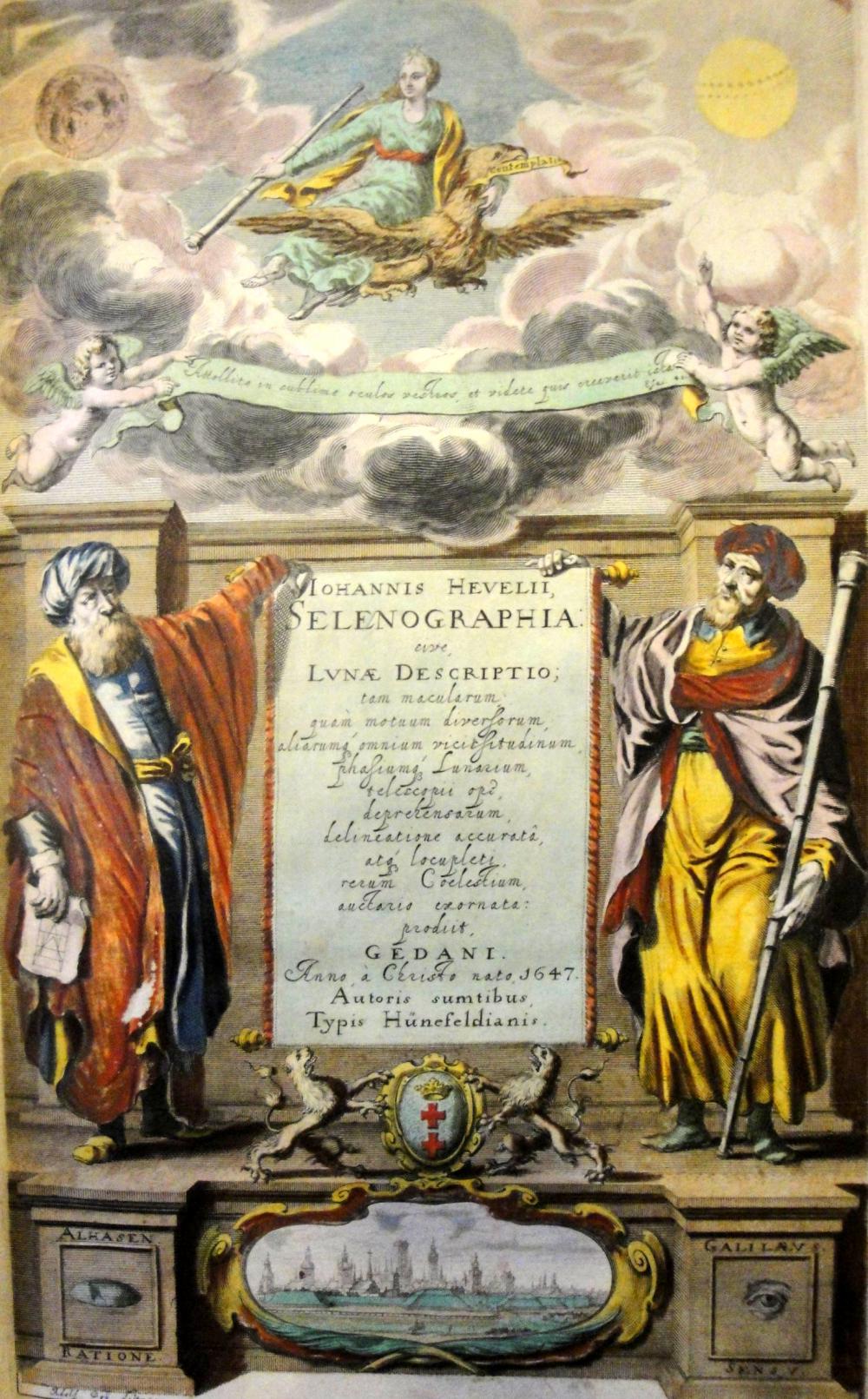

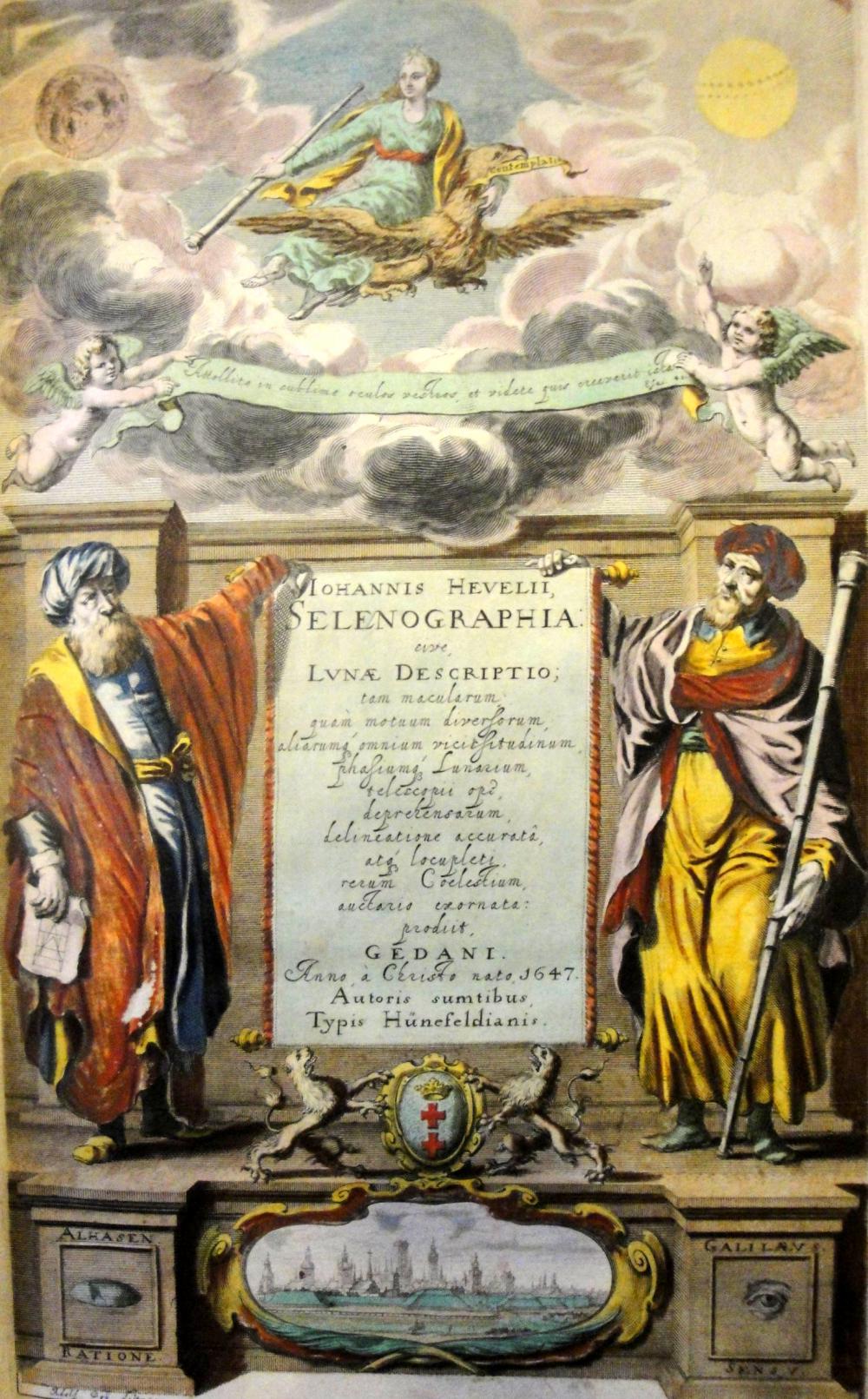

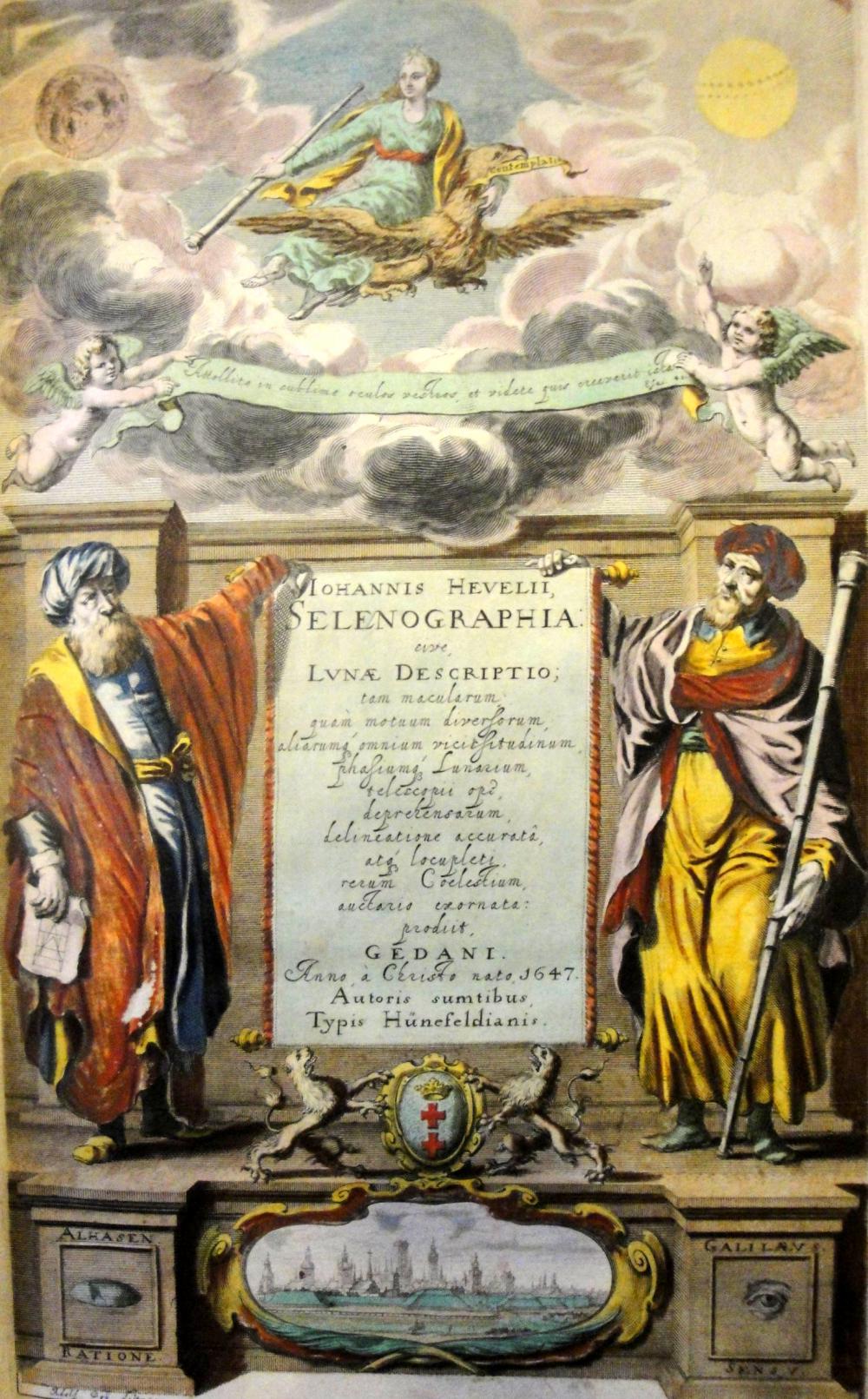

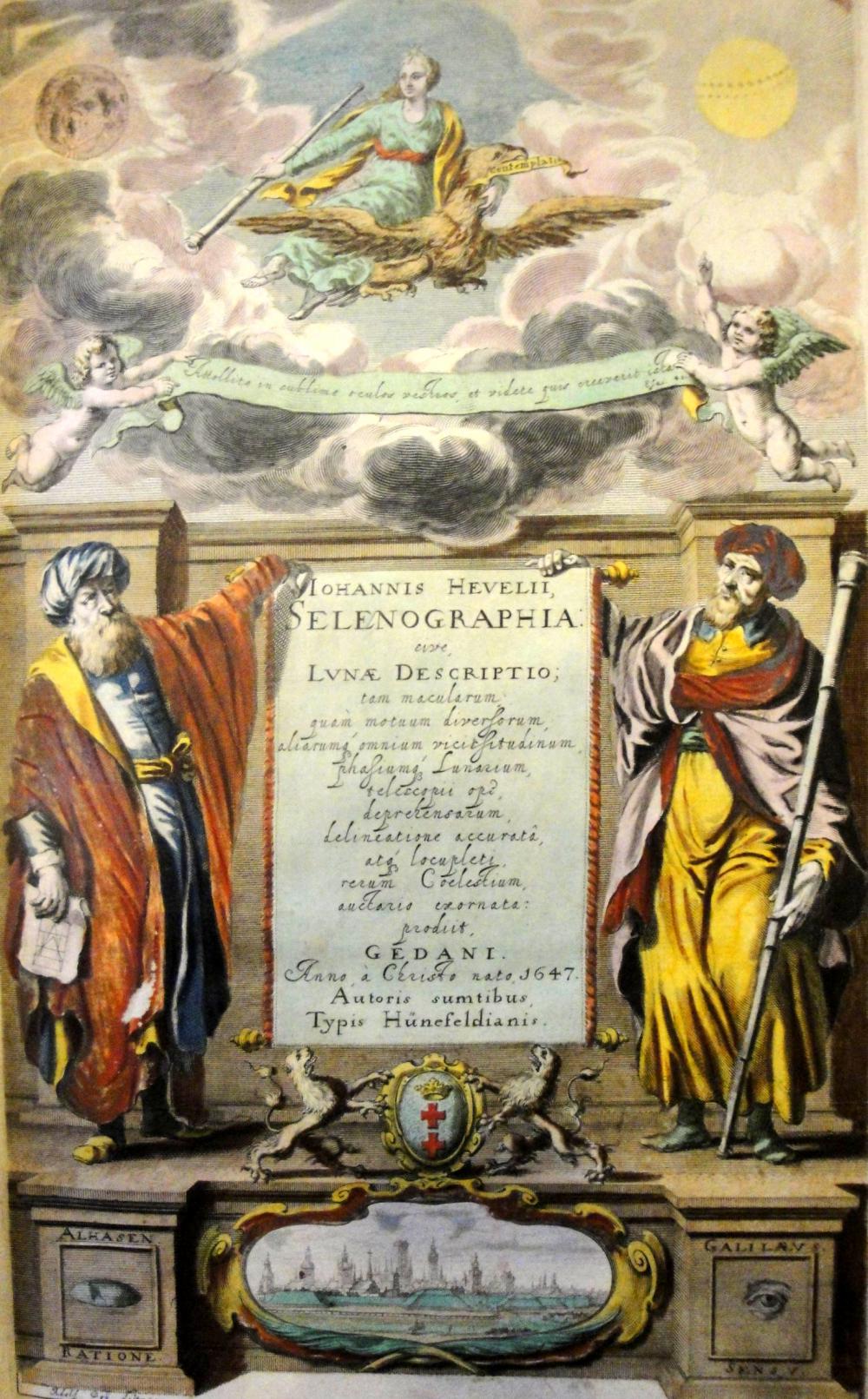

His most striking instrument was his telescope, 45m long, which was used for the detailed observation of lunar and planetary surfaces. This was the basis for the creation of his description of the moon "Selenographia sive Lunae Descriptio"tio" (Danzig 1647).

Publications - Hevelius’ scientifc output was remarkable:

- Selenographia (Danzig 1647)

- Mercurius in sole visus (Danzig: Simon Reiniger 1662)

- Cometographia (Danzig 1665)

- Machina coelestis. First part, containing a description of his instruments (Danzig 1673, 1679)

- Annus climactericus (Danzig 1685)

- Prodromus astronomiae (1690), posthumously published by Hevelius’ wife Catherina Elisabetha Koopman Hevelius in three books including:

- Prodromus, preface and unpublished observations

- Catalogus Stellarum Fixarum (dated 1687), catalogue of 1564 stars

- Firmamentum Sobiescianum sive Uranographia (dated 1687), an atlas of constellations

Hevelius introduced ten new star constellations; three of them were created after the devastation of his observatory and can be seen in the context of this big loss: the hound of Hades Cerberus, the Shield of Sobieski (scutum) and the sextant of Urania.

Fig. 12a. Hevelius observing the sun (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Fig. 12b. Hevelius observing the sun (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Fig. 13a. Hevelius first and last publication, "Selenographia" (1647)

Fig. 13b. Hevelius first and last publication, "Prodromus Astronomiae" (1690)

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-19 14:21:12

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Nothing is left from the burger houses where Hevelius’ observatory was.

There is however a nice model of Hevelius’ observatory in the Deutsches Museum Munich.

Fig. 14a. Hevelius’ observatory in Danzig and Hevelius observing quadrants without telescopic sights, model in the Deutsches Musem (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 14b. Hevelius’ observatory in Danzig and Hevelius observing quadrants without telescopic sights, model in the Deutsches Musem (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:39:52

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Hevelius was influenced by Tycho’s instruments. An extensive search for contemporary instruments in museums and old publications didn’t show many instruments that were influenced by Hevelius. Only the observatories in Nuremberg had some where Hevelius’ influence was obvious (at the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century).

Fig. 15a. Hevelius’ observatory in Danzig (Doppelmayr, J.G.: Atlas novus coelestis, Nürnberg 1742)

Fig. 15b. Nuremberg Eimmart observatory (Doppelmayr, J.G.: Atlas novus coelestis, Nürnberg 1742)

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:40:34

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no longer existing

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:43:02

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

A monument for Hevelius can be found in front of the Old City Hall in Gdańsk near the place of his home

and a second monument for Jan Heweliusz as well as a fountain.

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:43:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no longer existing

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:46:58

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Clerke, Agnes Mary: "Hevelius, Johann". In: Encyclopædia Britannica 13 (1911), (11th ed.), p. 416.

- Glc{e}bocki, Robert & Andrzej Zbierski: On the 300th anniversary of the death of Johannes Hevelius: book of The International Scientific Session. Ossolineum: The Polish Academy of Sciences, 1992, p. 56.

- Kampa, Irena: Vom Mauerquadranten zum Meridiankreis. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Sonne, Mond und Sterne - Meilensteine der Astronomiegeschichte. Zum 100jährigen Jubiläum der Hamburger Sternwarte in Bergedorf. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Band 29) 2013, S. 56-75.

- Kampa, Irena: Über den Dächern Danzigs - Die Sternwarte von Johannes Hevelius (1611--1687). In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Der Himmel über Tübingen. Barocksternwarten -- Landesvermessung -- Astrophysik. Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft 2013. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Band 28) 2014, S. 164-185.

- Kampa, Irena: Die astronomischen Instrumente von Johannes Hevelius. Dissertation, Universität Hamburg (Gutachter: Gudrun Wolfschmidt, Peter Hauschildt), 2017.

- Kampa, Irena: Die astronomischen Instrumente von Johannes Hevelius. Hg. von Gudrun Wolfschmidt. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 47) 2018.

- Kampa, Irena: Danzig -- die Heimatstadt des Astronomen Johannes Hevelius (1611--1687). In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Kiel 2015. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018, S. 202-219.

- King, Henry C.: The history of the telescope. Courier Dover Publ. 2003, p. 53.

- O’Connor, John J. & Edmund F. Robertson: Johannes Hevelius. In: MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- Schmeidler, Felix: Johannes Hevelius. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 9. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 1972, S. 59-61.

- Watson, Fred: Stargazer: The life and times of the telescope. Allen & Unwin 2004.

- Westphal, Johann Heinrich: Leben, Studien und Schriften des Astronomen Johann Hevelius. Königsberg 1820.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:47:52

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Polska Akademia Nauk (PAN) Biblioteka Gda’nska

http://www.bgpan.gda.pl/

- Prodromus astronomiae

https://polona.pl/item/436467

http://lhldigital.lindahall.org/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/astro_atlas&CISOPTR=1671&REC=11

- Galileo Project on Hevelius

http://galileo.rice.edu/Catalog/NewFiles/hevelius.html

- Paris Observatory - Hevelius’ letters

https://bibnum.obspm.fr/ark:/11287/1T1sQ

- Project to publish the correspondence of Hevelius at the International Academy of the History of Science

http://www.aihs-iahs.org/en/projects/hevelius

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-08-09 07:01:07

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Danzig / Gdańsk, Pfefferstadt, ulica Korzenna, houses No 47, 48 and 49 (not 53, 54 and 55) -

near the old city hall (Altstädtisches Rathaus) and church St. Bartholomäus.

Location - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 17:12:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Lat. 54° 21′ 15″ N, long. 18° 38′ 54″ E, elevation 33m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 12:34:35

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

A51

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:26:59

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Observatories of Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687)

For his instruments, Johannes Hevelius [Hewelcke, Polish Jan Heweliusz] (1611--1687) was very much inspired by Tycho Brahe (1546--1601), but concerning his private observatory, Hevelius had to choose a reasonably priced solution because he had no patron. Until the construction of the observatories in Greenwich and Paris in the 1670s, it was also the largest in Europe. Hevelius’ observatory developed parallel to the progress of its astronomical instruments.

Fig. 1. Observatories of Johannes Hevelius (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Irena Kampa (2017) describes in her thesis in great detail the astronomical instruments and compares them with instruments of other contemporary astronomers. Hevelius’ correspondence with European scientists served as the main source to find the makers of his devices. An examination of 22,000 single observational data provides new information about the usage of his instruments.

Fig. 2. Cover of the book of Kampa (2018)

Hevelius’ first observatory (1641)

In the beginning Hevelius did not have a fixed observing post but was star gazing from two nearby church towers with portable instruments.

In 1641, for his first observatory, he used four large roof windows for the small brass and also for the larger wooden instruments and also the big wooden instruments. In 1644 Hevelius received from the estate of his teacher Peter Crüger (1580-1639) the large azimuth quadrant; this instrument required a precise north-south orientation. Hevelius built a tower of octagonal shape with a diameter of 12 feet (about 3.3m) for this large wooden quadrant. For measuring time during observations Hevelius counted pendulum swings. He even constructed a machine to count them but was overtaken by Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695) and his patent on the pendulum clock.

Fig. 3. Hevelius observing with the quadrant and pendulum-clocks (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Fig. 4. Hevelius roof observatory, model in the Deutsches Musem (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Hevelius’ Stellaburgum - Hevelius’ second observatory (1650)

The second observatory was built around 1650. Hevelius erected a 25-by-50-foot wooden platform above the roofs of three adjacent burger houses of equal height. The drawing of J. Saal, engraved by Andrzej Stech, in "Machina Coelestis" (1673) shows Hevelius’ observatory very well.

- Looking at the buildings in the foreground on the left side there was a rotatable shelter, lower than platform; there his brass horizontal quadrant for meridian observations oriented in north-south direction was placed.

- Also for the large metal sextant and the metal octant a hut was built. It was standing on top of the north side of the main platform and it was also rotatable on wheels. In addition, it could be darkened and then used for solar observations.

- Finally, there was a third hut. There was for example a pallet for taking a rest, and in order to make it comfortable and pleasant for observers if waiting was necessary. In addition, devices, accessories and clocks were kept there.

Hevelius’ Stellaburgum, as he called his observatory, was probably also the first observatory with telescopes. This was the main purpose of the large platform that telescopes up to a length of about 50 foot could be handled.

It was very convinient that the observatory was at his home and not very far from his brewery or his workplace in the town hall as a mayor of Danzig; thus he was able to save a lot of time. Also inside of the observatory everything was quickly accessible from the living quarters, all the instruments, the library, the copper engraver workshop, the printing office.

Hevelius’ third observatory (after 1679)

In 1679 a great fire destroyed the observatory, in addition many instruments and manuscripts, prepared for printing as he reported in "Annus Climactericus" (1685). After the great fire, he decided immediately to reconstruct it and he erected a third observatory in 1681, just two years after the devastating fire. He started observing in 1682 but with very simple instrumentation.

Hevelius’ observing post outside of Danzig

The observing post for his giant telescope of 140 foot was only 1.5 km air-line distance from Hevelius’ Stellaburgum observatory in the city. Kampa (2018) could find out that the place was not at the hill near his garden in Oliva Road but it was in the street "Jana z Kolna" (coordinates of about 54°22’04’’ N and 18°38’17’’ E) near the Gdańsk Shipyard, about 400m north of the pedestrian bridge to the (later) railway station Gdańsk Stocznia. There he used occasionally his largest telescope of 140 foot.

Fig. 5. Hevelius observing post for his giant telescope of 140 foot outside of Danzig (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Design for a first observatory for using telescopes

Because observing with his largest telescope of 140 foot was not at all comfortable, he designed a new perfect telescope observatory in order to handle the long tubes. For the planned 150 foot telescope the tower which he used as mounting had to be about 100 to 120 foot high. The cross-section of his circular observatory should have a diameter of 12 to 15 foot. But due to his age he never succeeded to realize his dream.

Fig. 6. Hevelius design for a first observatory for using telescopes (Machina Coelestis, 1673), (Hamburg Observatory)

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 11

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:36:40

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687), brewer, mayor an astronomer, is famous for his outstanding astronomical instruments and his observatories of the 17th century. The observatory was erected on the roofs of his three houses in Danzig (Gdańsk). Most of his instruments Hevelius described in his "Machina Coelestis" (1673). Hevelius gained international fame already for his studies of the topography of the moon surface. A very detailed study was made by Kampa (2018); this is the basis of this presentation of highlights of Hevelius scientific work and making or using instruments.

Fig. 7. Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687), portrait in Trondheim (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Hevelius constructed his long telescope tubes following the example of Robert Hooke (16351703) who had sent him a drawing and instructions. He even printed this sketch on the frontispiece of his "Cometographia" (1668).

At the beginning of his career Hevelius experienced lens grinding and even tried to build a grinding machine for hyperbolic lenses. But later due to the lack of time he did no longer grind the lenses by himself. He bought most of his lenses from foreign opticians, e.g. Johann Wiesel (1617--1681) of Augsburg, Tito Livio Burattini (1617--1681) of Warsaw, Christopher Cock (~1660--1696) of London. Hevelius used telescopes with focal lengths 6 ft, 12 ft, 20 ft and 50 ft. Neither the 70 foot nor the 140 foot telescope, which Hevelius described in his "Machina Coelestis" (1673), were ever used for observations (Kampa 2018). The tube for the giant telescope, which Hevelius had build, before he received the lens, turned out to be too short. So Hevelius had no pioneering role regarding the evolution of giant and aerial telescopes.

Fig. 8. Hevelius’ workshop for grinding lenses ("Machina Coelestis", 1673)

In his third observatory Hevelius started to use a micrometer inserted into a 10 foot telescope to measure small angles. But his three big angle measuring devices made of metal (the azimuthal quadrant, the sextant and the octant) were by far his most frequently used instruments.

Fig. 9. Hevelius’ workshop for grinding lenses ("Cometographia", 1647), (Hamburg Observatory)

In order to derive the coordinates of the stars Hevelius used two calculating methods. For the distance method Hevelius needed three angular distances with two reference stars. For the altitude method on the other hand the meridian altitude and only one angular distance to a reference star were sufficient. The analysis of the manuscript of the star catalogue showed that Hevelius prefered the altitude method. The distance method was used mainly for stars with high declinations.

Hevelius’ first wife Catharina, born Rebeschke, (1613-1662), helped Hevelius to measure star distances. So far now only his second wife Elisabeth, born Koopman, (1647-1693), was famous for doing this. Since 1663, Elisabeth, 36 years younger, became his assistant and worked for 27 years with him. Johannes praised her as a clever co-operator in his publications. A stitch in "Machina coelestis" shows them observing together with the large sextant. In 1669 they published "Cometographia".

Fig. 10. Johannes and Elisabetha Hevelius observing (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

In 1661 Hevelius compiled a star catalogue of high accuracy "Prodromus astronomiae" (Danzig 1690) based on observations with `Tychonic’ instruments, without telescopic sights, which he built partly by himself. In 1679 Edmond Halley (1655--1742) visited Hevelius and checked the observing possibilities and results and was finally astonished that Hevelius was really able to determine stellar positions so well without a telescope.

Fig. 11. Hevelius’ telescopes from 10 to 50 foot (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

His most striking instrument was his telescope, 45m long, which was used for the detailed observation of lunar and planetary surfaces. This was the basis for the creation of his description of the moon "Selenographia sive Lunae Descriptio"tio" (Danzig 1647).

Publications - Hevelius’ scientifc output was remarkable:

- Selenographia (Danzig 1647)

- Mercurius in sole visus (Danzig: Simon Reiniger 1662)

- Cometographia (Danzig 1665)

- Machina coelestis. First part, containing a description of his instruments (Danzig 1673, 1679)

- Annus climactericus (Danzig 1685)

- Prodromus astronomiae (1690), posthumously published by Hevelius’ wife Catherina Elisabetha Koopman Hevelius in three books including:

- Prodromus, preface and unpublished observations

- Catalogus Stellarum Fixarum (dated 1687), catalogue of 1564 stars

- Firmamentum Sobiescianum sive Uranographia (dated 1687), an atlas of constellations

Hevelius introduced ten new star constellations; three of them were created after the devastation of his observatory and can be seen in the context of this big loss: the hound of Hades Cerberus, the Shield of Sobieski (scutum) and the sextant of Urania.

Fig. 12a. Hevelius observing the sun (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Fig. 12b. Hevelius observing the sun (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Fig. 13a. Hevelius first and last publication, "Selenographia" (1647)

Fig. 13b. Hevelius first and last publication, "Prodromus Astronomiae" (1690)

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-19 14:21:12

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Nothing is left from the burger houses where Hevelius’ observatory was.

There is however a nice model of Hevelius’ observatory in the Deutsches Museum Munich.

Fig. 14a. Hevelius’ observatory in Danzig and Hevelius observing quadrants without telescopic sights, model in the Deutsches Musem (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 14b. Hevelius’ observatory in Danzig and Hevelius observing quadrants without telescopic sights, model in the Deutsches Musem (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:39:52

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Hevelius was influenced by Tycho’s instruments. An extensive search for contemporary instruments in museums and old publications didn’t show many instruments that were influenced by Hevelius. Only the observatories in Nuremberg had some where Hevelius’ influence was obvious (at the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century).

Fig. 15a. Hevelius’ observatory in Danzig (Doppelmayr, J.G.: Atlas novus coelestis, Nürnberg 1742)

Fig. 15b. Nuremberg Eimmart observatory (Doppelmayr, J.G.: Atlas novus coelestis, Nürnberg 1742)

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:40:34

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no longer existing

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:43:02

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

A monument for Hevelius can be found in front of the Old City Hall in Gdańsk near the place of his home

and a second monument for Jan Heweliusz as well as a fountain.

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:43:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no longer existing

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:46:58

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Clerke, Agnes Mary: "Hevelius, Johann". In: Encyclopædia Britannica 13 (1911), (11th ed.), p. 416.

- Glc{e}bocki, Robert & Andrzej Zbierski: On the 300th anniversary of the death of Johannes Hevelius: book of The International Scientific Session. Ossolineum: The Polish Academy of Sciences, 1992, p. 56.

- Kampa, Irena: Vom Mauerquadranten zum Meridiankreis. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Sonne, Mond und Sterne - Meilensteine der Astronomiegeschichte. Zum 100jährigen Jubiläum der Hamburger Sternwarte in Bergedorf. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Band 29) 2013, S. 56-75.

- Kampa, Irena: Über den Dächern Danzigs - Die Sternwarte von Johannes Hevelius (1611--1687). In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Der Himmel über Tübingen. Barocksternwarten -- Landesvermessung -- Astrophysik. Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft 2013. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Band 28) 2014, S. 164-185.

- Kampa, Irena: Die astronomischen Instrumente von Johannes Hevelius. Dissertation, Universität Hamburg (Gutachter: Gudrun Wolfschmidt, Peter Hauschildt), 2017.

- Kampa, Irena: Die astronomischen Instrumente von Johannes Hevelius. Hg. von Gudrun Wolfschmidt. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 47) 2018.

- Kampa, Irena: Danzig -- die Heimatstadt des Astronomen Johannes Hevelius (1611--1687). In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Kiel 2015. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018, S. 202-219.

- King, Henry C.: The history of the telescope. Courier Dover Publ. 2003, p. 53.

- O’Connor, John J. & Edmund F. Robertson: Johannes Hevelius. In: MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- Schmeidler, Felix: Johannes Hevelius. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 9. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 1972, S. 59-61.

- Watson, Fred: Stargazer: The life and times of the telescope. Allen & Unwin 2004.

- Westphal, Johann Heinrich: Leben, Studien und Schriften des Astronomen Johann Hevelius. Königsberg 1820.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:47:52

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Polska Akademia Nauk (PAN) Biblioteka Gda’nska

http://www.bgpan.gda.pl/

- Prodromus astronomiae

https://polona.pl/item/436467

http://lhldigital.lindahall.org/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/astro_atlas&CISOPTR=1671&REC=11

- Galileo Project on Hevelius

http://galileo.rice.edu/Catalog/NewFiles/hevelius.html

- Paris Observatory - Hevelius’ letters

https://bibnum.obspm.fr/ark:/11287/1T1sQ

- Project to publish the correspondence of Hevelius at the International Academy of the History of Science

http://www.aihs-iahs.org/en/projects/hevelius

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 17:12:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Lat. 54° 21′ 15″ N, long. 18° 38′ 54″ E, elevation 33m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 12:34:35

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

A51

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:26:59

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Observatories of Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687)

For his instruments, Johannes Hevelius [Hewelcke, Polish Jan Heweliusz] (1611--1687) was very much inspired by Tycho Brahe (1546--1601), but concerning his private observatory, Hevelius had to choose a reasonably priced solution because he had no patron. Until the construction of the observatories in Greenwich and Paris in the 1670s, it was also the largest in Europe. Hevelius’ observatory developed parallel to the progress of its astronomical instruments.

Fig. 1. Observatories of Johannes Hevelius (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Irena Kampa (2017) describes in her thesis in great detail the astronomical instruments and compares them with instruments of other contemporary astronomers. Hevelius’ correspondence with European scientists served as the main source to find the makers of his devices. An examination of 22,000 single observational data provides new information about the usage of his instruments.

Fig. 2. Cover of the book of Kampa (2018)

Hevelius’ first observatory (1641)

In the beginning Hevelius did not have a fixed observing post but was star gazing from two nearby church towers with portable instruments.

In 1641, for his first observatory, he used four large roof windows for the small brass and also for the larger wooden instruments and also the big wooden instruments. In 1644 Hevelius received from the estate of his teacher Peter Crüger (1580-1639) the large azimuth quadrant; this instrument required a precise north-south orientation. Hevelius built a tower of octagonal shape with a diameter of 12 feet (about 3.3m) for this large wooden quadrant. For measuring time during observations Hevelius counted pendulum swings. He even constructed a machine to count them but was overtaken by Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695) and his patent on the pendulum clock.

Fig. 3. Hevelius observing with the quadrant and pendulum-clocks (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Fig. 4. Hevelius roof observatory, model in the Deutsches Musem (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Hevelius’ Stellaburgum - Hevelius’ second observatory (1650)

The second observatory was built around 1650. Hevelius erected a 25-by-50-foot wooden platform above the roofs of three adjacent burger houses of equal height. The drawing of J. Saal, engraved by Andrzej Stech, in "Machina Coelestis" (1673) shows Hevelius’ observatory very well.

- Looking at the buildings in the foreground on the left side there was a rotatable shelter, lower than platform; there his brass horizontal quadrant for meridian observations oriented in north-south direction was placed.

- Also for the large metal sextant and the metal octant a hut was built. It was standing on top of the north side of the main platform and it was also rotatable on wheels. In addition, it could be darkened and then used for solar observations.

- Finally, there was a third hut. There was for example a pallet for taking a rest, and in order to make it comfortable and pleasant for observers if waiting was necessary. In addition, devices, accessories and clocks were kept there.

Hevelius’ Stellaburgum, as he called his observatory, was probably also the first observatory with telescopes. This was the main purpose of the large platform that telescopes up to a length of about 50 foot could be handled.

It was very convinient that the observatory was at his home and not very far from his brewery or his workplace in the town hall as a mayor of Danzig; thus he was able to save a lot of time. Also inside of the observatory everything was quickly accessible from the living quarters, all the instruments, the library, the copper engraver workshop, the printing office.

Hevelius’ third observatory (after 1679)

In 1679 a great fire destroyed the observatory, in addition many instruments and manuscripts, prepared for printing as he reported in "Annus Climactericus" (1685). After the great fire, he decided immediately to reconstruct it and he erected a third observatory in 1681, just two years after the devastating fire. He started observing in 1682 but with very simple instrumentation.

Hevelius’ observing post outside of Danzig

The observing post for his giant telescope of 140 foot was only 1.5 km air-line distance from Hevelius’ Stellaburgum observatory in the city. Kampa (2018) could find out that the place was not at the hill near his garden in Oliva Road but it was in the street "Jana z Kolna" (coordinates of about 54°22’04’’ N and 18°38’17’’ E) near the Gdańsk Shipyard, about 400m north of the pedestrian bridge to the (later) railway station Gdańsk Stocznia. There he used occasionally his largest telescope of 140 foot.

Fig. 5. Hevelius observing post for his giant telescope of 140 foot outside of Danzig (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Design for a first observatory for using telescopes

Because observing with his largest telescope of 140 foot was not at all comfortable, he designed a new perfect telescope observatory in order to handle the long tubes. For the planned 150 foot telescope the tower which he used as mounting had to be about 100 to 120 foot high. The cross-section of his circular observatory should have a diameter of 12 to 15 foot. But due to his age he never succeeded to realize his dream.

Fig. 6. Hevelius design for a first observatory for using telescopes (Machina Coelestis, 1673), (Hamburg Observatory)

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 11

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:36:40

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687), brewer, mayor an astronomer, is famous for his outstanding astronomical instruments and his observatories of the 17th century. The observatory was erected on the roofs of his three houses in Danzig (Gdańsk). Most of his instruments Hevelius described in his "Machina Coelestis" (1673). Hevelius gained international fame already for his studies of the topography of the moon surface. A very detailed study was made by Kampa (2018); this is the basis of this presentation of highlights of Hevelius scientific work and making or using instruments.

Fig. 7. Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687), portrait in Trondheim (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Hevelius constructed his long telescope tubes following the example of Robert Hooke (16351703) who had sent him a drawing and instructions. He even printed this sketch on the frontispiece of his "Cometographia" (1668).

At the beginning of his career Hevelius experienced lens grinding and even tried to build a grinding machine for hyperbolic lenses. But later due to the lack of time he did no longer grind the lenses by himself. He bought most of his lenses from foreign opticians, e.g. Johann Wiesel (1617--1681) of Augsburg, Tito Livio Burattini (1617--1681) of Warsaw, Christopher Cock (~1660--1696) of London. Hevelius used telescopes with focal lengths 6 ft, 12 ft, 20 ft and 50 ft. Neither the 70 foot nor the 140 foot telescope, which Hevelius described in his "Machina Coelestis" (1673), were ever used for observations (Kampa 2018). The tube for the giant telescope, which Hevelius had build, before he received the lens, turned out to be too short. So Hevelius had no pioneering role regarding the evolution of giant and aerial telescopes.

Fig. 8. Hevelius’ workshop for grinding lenses ("Machina Coelestis", 1673)

In his third observatory Hevelius started to use a micrometer inserted into a 10 foot telescope to measure small angles. But his three big angle measuring devices made of metal (the azimuthal quadrant, the sextant and the octant) were by far his most frequently used instruments.

Fig. 9. Hevelius’ workshop for grinding lenses ("Cometographia", 1647), (Hamburg Observatory)

In order to derive the coordinates of the stars Hevelius used two calculating methods. For the distance method Hevelius needed three angular distances with two reference stars. For the altitude method on the other hand the meridian altitude and only one angular distance to a reference star were sufficient. The analysis of the manuscript of the star catalogue showed that Hevelius prefered the altitude method. The distance method was used mainly for stars with high declinations.

Hevelius’ first wife Catharina, born Rebeschke, (1613-1662), helped Hevelius to measure star distances. So far now only his second wife Elisabeth, born Koopman, (1647-1693), was famous for doing this. Since 1663, Elisabeth, 36 years younger, became his assistant and worked for 27 years with him. Johannes praised her as a clever co-operator in his publications. A stitch in "Machina coelestis" shows them observing together with the large sextant. In 1669 they published "Cometographia".

Fig. 10. Johannes and Elisabetha Hevelius observing (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

In 1661 Hevelius compiled a star catalogue of high accuracy "Prodromus astronomiae" (Danzig 1690) based on observations with `Tychonic’ instruments, without telescopic sights, which he built partly by himself. In 1679 Edmond Halley (1655--1742) visited Hevelius and checked the observing possibilities and results and was finally astonished that Hevelius was really able to determine stellar positions so well without a telescope.

Fig. 11. Hevelius’ telescopes from 10 to 50 foot (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

His most striking instrument was his telescope, 45m long, which was used for the detailed observation of lunar and planetary surfaces. This was the basis for the creation of his description of the moon "Selenographia sive Lunae Descriptio"tio" (Danzig 1647).

Publications - Hevelius’ scientifc output was remarkable:

- Selenographia (Danzig 1647)

- Mercurius in sole visus (Danzig: Simon Reiniger 1662)

- Cometographia (Danzig 1665)

- Machina coelestis. First part, containing a description of his instruments (Danzig 1673, 1679)

- Annus climactericus (Danzig 1685)

- Prodromus astronomiae (1690), posthumously published by Hevelius’ wife Catherina Elisabetha Koopman Hevelius in three books including:

- Prodromus, preface and unpublished observations

- Catalogus Stellarum Fixarum (dated 1687), catalogue of 1564 stars

- Firmamentum Sobiescianum sive Uranographia (dated 1687), an atlas of constellations

Hevelius introduced ten new star constellations; three of them were created after the devastation of his observatory and can be seen in the context of this big loss: the hound of Hades Cerberus, the Shield of Sobieski (scutum) and the sextant of Urania.

Fig. 12a. Hevelius observing the sun (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Fig. 12b. Hevelius observing the sun (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Fig. 13a. Hevelius first and last publication, "Selenographia" (1647)

Fig. 13b. Hevelius first and last publication, "Prodromus Astronomiae" (1690)

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-19 14:21:12

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Nothing is left from the burger houses where Hevelius’ observatory was.

There is however a nice model of Hevelius’ observatory in the Deutsches Museum Munich.

Fig. 14a. Hevelius’ observatory in Danzig and Hevelius observing quadrants without telescopic sights, model in the Deutsches Musem (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 14b. Hevelius’ observatory in Danzig and Hevelius observing quadrants without telescopic sights, model in the Deutsches Musem (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:39:52

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Hevelius was influenced by Tycho’s instruments. An extensive search for contemporary instruments in museums and old publications didn’t show many instruments that were influenced by Hevelius. Only the observatories in Nuremberg had some where Hevelius’ influence was obvious (at the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century).

Fig. 15a. Hevelius’ observatory in Danzig (Doppelmayr, J.G.: Atlas novus coelestis, Nürnberg 1742)

Fig. 15b. Nuremberg Eimmart observatory (Doppelmayr, J.G.: Atlas novus coelestis, Nürnberg 1742)

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:40:34

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no longer existing

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:43:02

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

A monument for Hevelius can be found in front of the Old City Hall in Gdańsk near the place of his home

and a second monument for Jan Heweliusz as well as a fountain.

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:43:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no longer existing

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:46:58

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Clerke, Agnes Mary: "Hevelius, Johann". In: Encyclopædia Britannica 13 (1911), (11th ed.), p. 416.

- Glc{e}bocki, Robert & Andrzej Zbierski: On the 300th anniversary of the death of Johannes Hevelius: book of The International Scientific Session. Ossolineum: The Polish Academy of Sciences, 1992, p. 56.

- Kampa, Irena: Vom Mauerquadranten zum Meridiankreis. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Sonne, Mond und Sterne - Meilensteine der Astronomiegeschichte. Zum 100jährigen Jubiläum der Hamburger Sternwarte in Bergedorf. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Band 29) 2013, S. 56-75.

- Kampa, Irena: Über den Dächern Danzigs - Die Sternwarte von Johannes Hevelius (1611--1687). In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Der Himmel über Tübingen. Barocksternwarten -- Landesvermessung -- Astrophysik. Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft 2013. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Band 28) 2014, S. 164-185.

- Kampa, Irena: Die astronomischen Instrumente von Johannes Hevelius. Dissertation, Universität Hamburg (Gutachter: Gudrun Wolfschmidt, Peter Hauschildt), 2017.

- Kampa, Irena: Die astronomischen Instrumente von Johannes Hevelius. Hg. von Gudrun Wolfschmidt. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 47) 2018.

- Kampa, Irena: Danzig -- die Heimatstadt des Astronomen Johannes Hevelius (1611--1687). In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Kiel 2015. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018, S. 202-219.

- King, Henry C.: The history of the telescope. Courier Dover Publ. 2003, p. 53.

- O’Connor, John J. & Edmund F. Robertson: Johannes Hevelius. In: MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- Schmeidler, Felix: Johannes Hevelius. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 9. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 1972, S. 59-61.

- Watson, Fred: Stargazer: The life and times of the telescope. Allen & Unwin 2004.

- Westphal, Johann Heinrich: Leben, Studien und Schriften des Astronomen Johann Hevelius. Königsberg 1820.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:47:52

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Polska Akademia Nauk (PAN) Biblioteka Gda’nska

http://www.bgpan.gda.pl/

- Prodromus astronomiae

https://polona.pl/item/436467

http://lhldigital.lindahall.org/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/astro_atlas&CISOPTR=1671&REC=11

- Galileo Project on Hevelius

http://galileo.rice.edu/Catalog/NewFiles/hevelius.html

- Paris Observatory - Hevelius’ letters

https://bibnum.obspm.fr/ark:/11287/1T1sQ

- Project to publish the correspondence of Hevelius at the International Academy of the History of Science

http://www.aihs-iahs.org/en/projects/hevelius

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-17 12:34:35

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

A51

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:26:59

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Observatories of Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687)

For his instruments, Johannes Hevelius [Hewelcke, Polish Jan Heweliusz] (1611--1687) was very much inspired by Tycho Brahe (1546--1601), but concerning his private observatory, Hevelius had to choose a reasonably priced solution because he had no patron. Until the construction of the observatories in Greenwich and Paris in the 1670s, it was also the largest in Europe. Hevelius’ observatory developed parallel to the progress of its astronomical instruments.

Fig. 1. Observatories of Johannes Hevelius (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Irena Kampa (2017) describes in her thesis in great detail the astronomical instruments and compares them with instruments of other contemporary astronomers. Hevelius’ correspondence with European scientists served as the main source to find the makers of his devices. An examination of 22,000 single observational data provides new information about the usage of his instruments.

Fig. 2. Cover of the book of Kampa (2018)

Hevelius’ first observatory (1641)

In the beginning Hevelius did not have a fixed observing post but was star gazing from two nearby church towers with portable instruments.

In 1641, for his first observatory, he used four large roof windows for the small brass and also for the larger wooden instruments and also the big wooden instruments. In 1644 Hevelius received from the estate of his teacher Peter Crüger (1580-1639) the large azimuth quadrant; this instrument required a precise north-south orientation. Hevelius built a tower of octagonal shape with a diameter of 12 feet (about 3.3m) for this large wooden quadrant. For measuring time during observations Hevelius counted pendulum swings. He even constructed a machine to count them but was overtaken by Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695) and his patent on the pendulum clock.

Fig. 3. Hevelius observing with the quadrant and pendulum-clocks (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Fig. 4. Hevelius roof observatory, model in the Deutsches Musem (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Hevelius’ Stellaburgum - Hevelius’ second observatory (1650)

The second observatory was built around 1650. Hevelius erected a 25-by-50-foot wooden platform above the roofs of three adjacent burger houses of equal height. The drawing of J. Saal, engraved by Andrzej Stech, in "Machina Coelestis" (1673) shows Hevelius’ observatory very well.

- Looking at the buildings in the foreground on the left side there was a rotatable shelter, lower than platform; there his brass horizontal quadrant for meridian observations oriented in north-south direction was placed.

- Also for the large metal sextant and the metal octant a hut was built. It was standing on top of the north side of the main platform and it was also rotatable on wheels. In addition, it could be darkened and then used for solar observations.

- Finally, there was a third hut. There was for example a pallet for taking a rest, and in order to make it comfortable and pleasant for observers if waiting was necessary. In addition, devices, accessories and clocks were kept there.

Hevelius’ Stellaburgum, as he called his observatory, was probably also the first observatory with telescopes. This was the main purpose of the large platform that telescopes up to a length of about 50 foot could be handled.

It was very convinient that the observatory was at his home and not very far from his brewery or his workplace in the town hall as a mayor of Danzig; thus he was able to save a lot of time. Also inside of the observatory everything was quickly accessible from the living quarters, all the instruments, the library, the copper engraver workshop, the printing office.

Hevelius’ third observatory (after 1679)

In 1679 a great fire destroyed the observatory, in addition many instruments and manuscripts, prepared for printing as he reported in "Annus Climactericus" (1685). After the great fire, he decided immediately to reconstruct it and he erected a third observatory in 1681, just two years after the devastating fire. He started observing in 1682 but with very simple instrumentation.

Hevelius’ observing post outside of Danzig

The observing post for his giant telescope of 140 foot was only 1.5 km air-line distance from Hevelius’ Stellaburgum observatory in the city. Kampa (2018) could find out that the place was not at the hill near his garden in Oliva Road but it was in the street "Jana z Kolna" (coordinates of about 54°22’04’’ N and 18°38’17’’ E) near the Gdańsk Shipyard, about 400m north of the pedestrian bridge to the (later) railway station Gdańsk Stocznia. There he used occasionally his largest telescope of 140 foot.

Fig. 5. Hevelius observing post for his giant telescope of 140 foot outside of Danzig (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Design for a first observatory for using telescopes

Because observing with his largest telescope of 140 foot was not at all comfortable, he designed a new perfect telescope observatory in order to handle the long tubes. For the planned 150 foot telescope the tower which he used as mounting had to be about 100 to 120 foot high. The cross-section of his circular observatory should have a diameter of 12 to 15 foot. But due to his age he never succeeded to realize his dream.

Fig. 6. Hevelius design for a first observatory for using telescopes (Machina Coelestis, 1673), (Hamburg Observatory)

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 11

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:36:40

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687), brewer, mayor an astronomer, is famous for his outstanding astronomical instruments and his observatories of the 17th century. The observatory was erected on the roofs of his three houses in Danzig (Gdańsk). Most of his instruments Hevelius described in his "Machina Coelestis" (1673). Hevelius gained international fame already for his studies of the topography of the moon surface. A very detailed study was made by Kampa (2018); this is the basis of this presentation of highlights of Hevelius scientific work and making or using instruments.

Fig. 7. Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687), portrait in Trondheim (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Hevelius constructed his long telescope tubes following the example of Robert Hooke (16351703) who had sent him a drawing and instructions. He even printed this sketch on the frontispiece of his "Cometographia" (1668).

At the beginning of his career Hevelius experienced lens grinding and even tried to build a grinding machine for hyperbolic lenses. But later due to the lack of time he did no longer grind the lenses by himself. He bought most of his lenses from foreign opticians, e.g. Johann Wiesel (1617--1681) of Augsburg, Tito Livio Burattini (1617--1681) of Warsaw, Christopher Cock (~1660--1696) of London. Hevelius used telescopes with focal lengths 6 ft, 12 ft, 20 ft and 50 ft. Neither the 70 foot nor the 140 foot telescope, which Hevelius described in his "Machina Coelestis" (1673), were ever used for observations (Kampa 2018). The tube for the giant telescope, which Hevelius had build, before he received the lens, turned out to be too short. So Hevelius had no pioneering role regarding the evolution of giant and aerial telescopes.

Fig. 8. Hevelius’ workshop for grinding lenses ("Machina Coelestis", 1673)

In his third observatory Hevelius started to use a micrometer inserted into a 10 foot telescope to measure small angles. But his three big angle measuring devices made of metal (the azimuthal quadrant, the sextant and the octant) were by far his most frequently used instruments.

Fig. 9. Hevelius’ workshop for grinding lenses ("Cometographia", 1647), (Hamburg Observatory)

In order to derive the coordinates of the stars Hevelius used two calculating methods. For the distance method Hevelius needed three angular distances with two reference stars. For the altitude method on the other hand the meridian altitude and only one angular distance to a reference star were sufficient. The analysis of the manuscript of the star catalogue showed that Hevelius prefered the altitude method. The distance method was used mainly for stars with high declinations.

Hevelius’ first wife Catharina, born Rebeschke, (1613-1662), helped Hevelius to measure star distances. So far now only his second wife Elisabeth, born Koopman, (1647-1693), was famous for doing this. Since 1663, Elisabeth, 36 years younger, became his assistant and worked for 27 years with him. Johannes praised her as a clever co-operator in his publications. A stitch in "Machina coelestis" shows them observing together with the large sextant. In 1669 they published "Cometographia".

Fig. 10. Johannes and Elisabetha Hevelius observing (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

In 1661 Hevelius compiled a star catalogue of high accuracy "Prodromus astronomiae" (Danzig 1690) based on observations with `Tychonic’ instruments, without telescopic sights, which he built partly by himself. In 1679 Edmond Halley (1655--1742) visited Hevelius and checked the observing possibilities and results and was finally astonished that Hevelius was really able to determine stellar positions so well without a telescope.

Fig. 11. Hevelius’ telescopes from 10 to 50 foot (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

His most striking instrument was his telescope, 45m long, which was used for the detailed observation of lunar and planetary surfaces. This was the basis for the creation of his description of the moon "Selenographia sive Lunae Descriptio"tio" (Danzig 1647).

Publications - Hevelius’ scientifc output was remarkable:

- Selenographia (Danzig 1647)

- Mercurius in sole visus (Danzig: Simon Reiniger 1662)

- Cometographia (Danzig 1665)

- Machina coelestis. First part, containing a description of his instruments (Danzig 1673, 1679)

- Annus climactericus (Danzig 1685)

- Prodromus astronomiae (1690), posthumously published by Hevelius’ wife Catherina Elisabetha Koopman Hevelius in three books including:

- Prodromus, preface and unpublished observations

- Catalogus Stellarum Fixarum (dated 1687), catalogue of 1564 stars

- Firmamentum Sobiescianum sive Uranographia (dated 1687), an atlas of constellations

Hevelius introduced ten new star constellations; three of them were created after the devastation of his observatory and can be seen in the context of this big loss: the hound of Hades Cerberus, the Shield of Sobieski (scutum) and the sextant of Urania.

Fig. 12a. Hevelius observing the sun (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Fig. 12b. Hevelius observing the sun (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Fig. 13a. Hevelius first and last publication, "Selenographia" (1647)

Fig. 13b. Hevelius first and last publication, "Prodromus Astronomiae" (1690)

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2019-06-19 14:21:12

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Nothing is left from the burger houses where Hevelius’ observatory was.

There is however a nice model of Hevelius’ observatory in the Deutsches Museum Munich.

Fig. 14a. Hevelius’ observatory in Danzig and Hevelius observing quadrants without telescopic sights, model in the Deutsches Musem (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 14b. Hevelius’ observatory in Danzig and Hevelius observing quadrants without telescopic sights, model in the Deutsches Musem (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:39:52

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Hevelius was influenced by Tycho’s instruments. An extensive search for contemporary instruments in museums and old publications didn’t show many instruments that were influenced by Hevelius. Only the observatories in Nuremberg had some where Hevelius’ influence was obvious (at the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century).

Fig. 15a. Hevelius’ observatory in Danzig (Doppelmayr, J.G.: Atlas novus coelestis, Nürnberg 1742)

Fig. 15b. Nuremberg Eimmart observatory (Doppelmayr, J.G.: Atlas novus coelestis, Nürnberg 1742)

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:40:34

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no longer existing

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:43:02

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

A monument for Hevelius can be found in front of the Old City Hall in Gdańsk near the place of his home

and a second monument for Jan Heweliusz as well as a fountain.

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:43:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no longer existing

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:46:58

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Clerke, Agnes Mary: "Hevelius, Johann". In: Encyclopædia Britannica 13 (1911), (11th ed.), p. 416.

- Glc{e}bocki, Robert & Andrzej Zbierski: On the 300th anniversary of the death of Johannes Hevelius: book of The International Scientific Session. Ossolineum: The Polish Academy of Sciences, 1992, p. 56.

- Kampa, Irena: Vom Mauerquadranten zum Meridiankreis. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Sonne, Mond und Sterne - Meilensteine der Astronomiegeschichte. Zum 100jährigen Jubiläum der Hamburger Sternwarte in Bergedorf. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Band 29) 2013, S. 56-75.

- Kampa, Irena: Über den Dächern Danzigs - Die Sternwarte von Johannes Hevelius (1611--1687). In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Der Himmel über Tübingen. Barocksternwarten -- Landesvermessung -- Astrophysik. Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft 2013. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Band 28) 2014, S. 164-185.

- Kampa, Irena: Die astronomischen Instrumente von Johannes Hevelius. Dissertation, Universität Hamburg (Gutachter: Gudrun Wolfschmidt, Peter Hauschildt), 2017.

- Kampa, Irena: Die astronomischen Instrumente von Johannes Hevelius. Hg. von Gudrun Wolfschmidt. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 47) 2018.

- Kampa, Irena: Danzig -- die Heimatstadt des Astronomen Johannes Hevelius (1611--1687). In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Kiel 2015. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018, S. 202-219.

- King, Henry C.: The history of the telescope. Courier Dover Publ. 2003, p. 53.

- O’Connor, John J. & Edmund F. Robertson: Johannes Hevelius. In: MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- Schmeidler, Felix: Johannes Hevelius. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 9. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 1972, S. 59-61.

- Watson, Fred: Stargazer: The life and times of the telescope. Allen & Unwin 2004.

- Westphal, Johann Heinrich: Leben, Studien und Schriften des Astronomen Johann Hevelius. Königsberg 1820.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:47:52

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Polska Akademia Nauk (PAN) Biblioteka Gda’nska

http://www.bgpan.gda.pl/

- Prodromus astronomiae

https://polona.pl/item/436467

http://lhldigital.lindahall.org/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/astro_atlas&CISOPTR=1671&REC=11

- Galileo Project on Hevelius

http://galileo.rice.edu/Catalog/NewFiles/hevelius.html

- Paris Observatory - Hevelius’ letters

https://bibnum.obspm.fr/ark:/11287/1T1sQ

- Project to publish the correspondence of Hevelius at the International Academy of the History of Science

http://www.aihs-iahs.org/en/projects/hevelius

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:26:59

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Observatories of Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687)

For his instruments, Johannes Hevelius [Hewelcke, Polish Jan Heweliusz] (1611--1687) was very much inspired by Tycho Brahe (1546--1601), but concerning his private observatory, Hevelius had to choose a reasonably priced solution because he had no patron. Until the construction of the observatories in Greenwich and Paris in the 1670s, it was also the largest in Europe. Hevelius’ observatory developed parallel to the progress of its astronomical instruments.

Fig. 1. Observatories of Johannes Hevelius (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Irena Kampa (2017) describes in her thesis in great detail the astronomical instruments and compares them with instruments of other contemporary astronomers. Hevelius’ correspondence with European scientists served as the main source to find the makers of his devices. An examination of 22,000 single observational data provides new information about the usage of his instruments.

Fig. 2. Cover of the book of Kampa (2018)

Hevelius’ first observatory (1641)

In the beginning Hevelius did not have a fixed observing post but was star gazing from two nearby church towers with portable instruments.

In 1641, for his first observatory, he used four large roof windows for the small brass and also for the larger wooden instruments and also the big wooden instruments. In 1644 Hevelius received from the estate of his teacher Peter Crüger (1580-1639) the large azimuth quadrant; this instrument required a precise north-south orientation. Hevelius built a tower of octagonal shape with a diameter of 12 feet (about 3.3m) for this large wooden quadrant. For measuring time during observations Hevelius counted pendulum swings. He even constructed a machine to count them but was overtaken by Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695) and his patent on the pendulum clock.

Fig. 3. Hevelius observing with the quadrant and pendulum-clocks (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Fig. 4. Hevelius roof observatory, model in the Deutsches Musem (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Hevelius’ Stellaburgum - Hevelius’ second observatory (1650)

The second observatory was built around 1650. Hevelius erected a 25-by-50-foot wooden platform above the roofs of three adjacent burger houses of equal height. The drawing of J. Saal, engraved by Andrzej Stech, in "Machina Coelestis" (1673) shows Hevelius’ observatory very well.

- Looking at the buildings in the foreground on the left side there was a rotatable shelter, lower than platform; there his brass horizontal quadrant for meridian observations oriented in north-south direction was placed.

- Also for the large metal sextant and the metal octant a hut was built. It was standing on top of the north side of the main platform and it was also rotatable on wheels. In addition, it could be darkened and then used for solar observations.

- Finally, there was a third hut. There was for example a pallet for taking a rest, and in order to make it comfortable and pleasant for observers if waiting was necessary. In addition, devices, accessories and clocks were kept there.

Hevelius’ Stellaburgum, as he called his observatory, was probably also the first observatory with telescopes. This was the main purpose of the large platform that telescopes up to a length of about 50 foot could be handled.

It was very convinient that the observatory was at his home and not very far from his brewery or his workplace in the town hall as a mayor of Danzig; thus he was able to save a lot of time. Also inside of the observatory everything was quickly accessible from the living quarters, all the instruments, the library, the copper engraver workshop, the printing office.

Hevelius’ third observatory (after 1679)

In 1679 a great fire destroyed the observatory, in addition many instruments and manuscripts, prepared for printing as he reported in "Annus Climactericus" (1685). After the great fire, he decided immediately to reconstruct it and he erected a third observatory in 1681, just two years after the devastating fire. He started observing in 1682 but with very simple instrumentation.

Hevelius’ observing post outside of Danzig

The observing post for his giant telescope of 140 foot was only 1.5 km air-line distance from Hevelius’ Stellaburgum observatory in the city. Kampa (2018) could find out that the place was not at the hill near his garden in Oliva Road but it was in the street "Jana z Kolna" (coordinates of about 54°22’04’’ N and 18°38’17’’ E) near the Gdańsk Shipyard, about 400m north of the pedestrian bridge to the (later) railway station Gdańsk Stocznia. There he used occasionally his largest telescope of 140 foot.

Fig. 5. Hevelius observing post for his giant telescope of 140 foot outside of Danzig (Machina Coelestis, 1673)

Design for a first observatory for using telescopes

Because observing with his largest telescope of 140 foot was not at all comfortable, he designed a new perfect telescope observatory in order to handle the long tubes. For the planned 150 foot telescope the tower which he used as mounting had to be about 100 to 120 foot high. The cross-section of his circular observatory should have a diameter of 12 to 15 foot. But due to his age he never succeeded to realize his dream.

Fig. 6. Hevelius design for a first observatory for using telescopes (Machina Coelestis, 1673), (Hamburg Observatory)

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 101

Subentity: 1

Version: 11

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-03-14 16:36:40

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687), brewer, mayor an astronomer, is famous for his outstanding astronomical instruments and his observatories of the 17th century. The observatory was erected on the roofs of his three houses in Danzig (Gdańsk). Most of his instruments Hevelius described in his "Machina Coelestis" (1673). Hevelius gained international fame already for his studies of the topography of the moon surface. A very detailed study was made by Kampa (2018); this is the basis of this presentation of highlights of Hevelius scientific work and making or using instruments.

Fig. 7. Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687), portrait in Trondheim (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Hevelius constructed his long telescope tubes following the example of Robert Hooke (16351703) who had sent him a drawing and instructions. He even printed this sketch on the frontispiece of his "Cometographia" (1668).