Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Madras Observatory, India

Format: IAU - Outstanding Astronomical Heritage

Description

Geographical position - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:34:45

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Madras Observatory, Madras (Chennai), Tamil Nadu, India

(today: Indian Institute of Astrophysics)

Location - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:35:39

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude 13°04’05’’ N, Longitude 80°14’48’’ E, Elevation 16m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-08-13 10:15:12

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

223

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-04 09:32:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Jesuit astronomers arrived at Jaipur in 1734, and established the longitude of several of Jai Singh II’s cities. The Jesuits studyed Sanskrit, in order to translate the greatest works of South Asian astronomy. Sawai Jai Singh II (1688--1743), Maharaja of Amber and Jaipur, was considerably interested in mathematics, architecture and astronomy; very famous are his five observatories in Jaipur, Dehli, Mathura (Agra province), Varanasi (Benares province), Ujjain (Malwa province) -- large sundials and calendar buildings in order to determine time and date, or to measure the altitude and azimuth of celestial objects. But Jai Singh II’s observatrories lacked telescopes, which had been invented in Europe a century before.

But the influence of the Jesuits in India was not very long. After Jai Singh II died, the time of the Jesuits came already to an end. Then the British East India Company dominated. For the East India Company in the 1780s two things were important: navigation (time keeping, also for getting the longitude) and land surveying. Later in 1860, also geomagnetism was included besides astronomy.

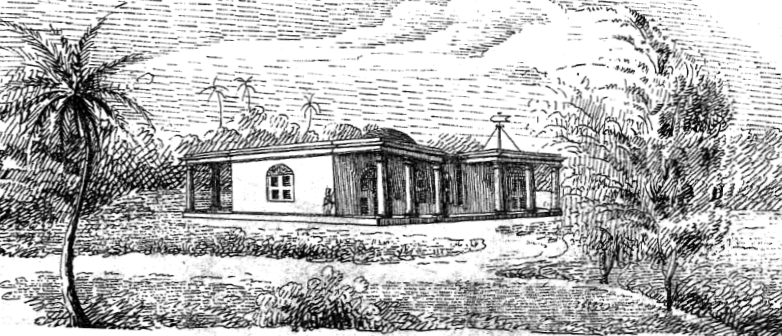

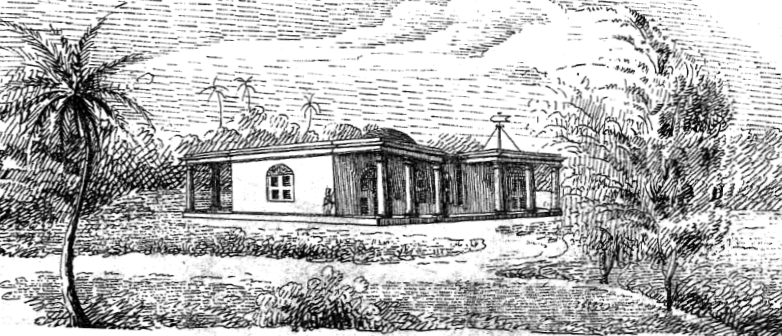

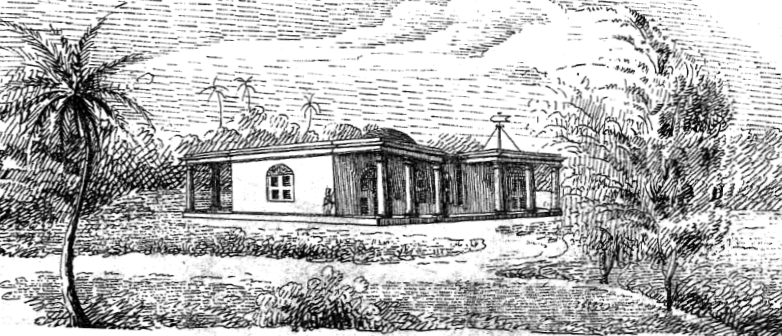

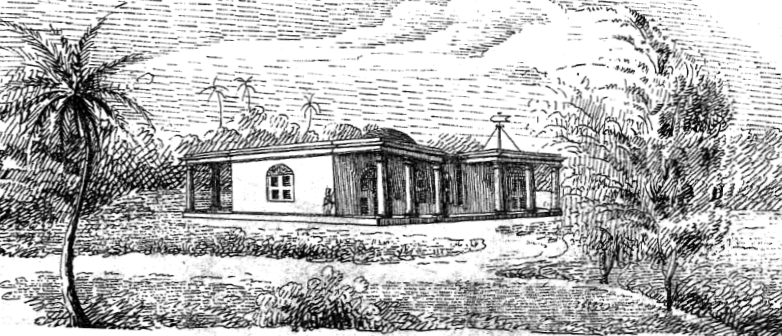

Fig. 1. Old Madras Observatory, Egmore in Madras (1786), woodcut (Taylor 1838), (Wikipedia)

Madras Observatory (1786) was one of the first modern observatories in Asia. William Petrie (1784--1816) started to establish Madras Observatory in 1786 as a private observatory, made of iron and timber. Petrie donated his instruments to the Madras Government before retiring to England.

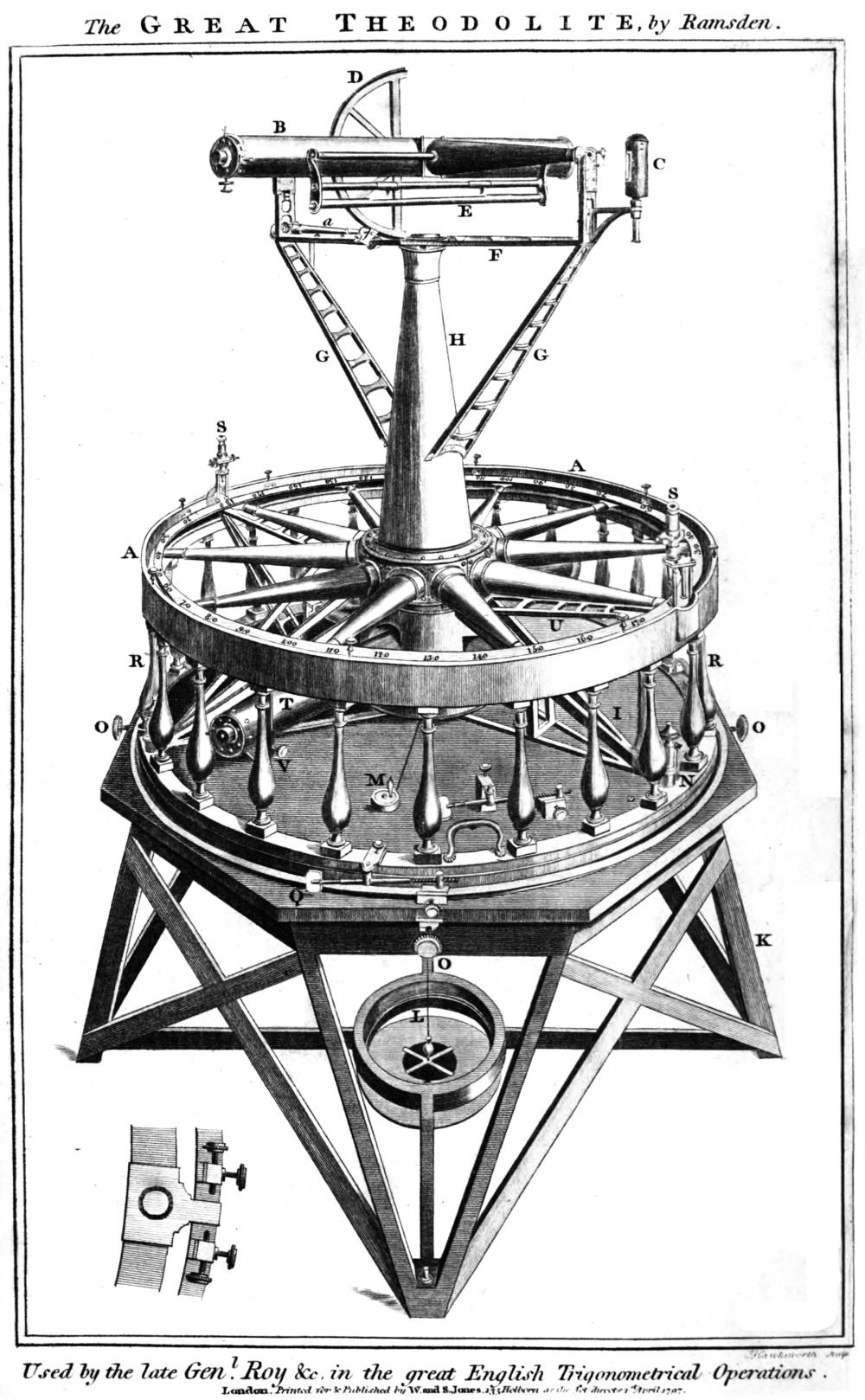

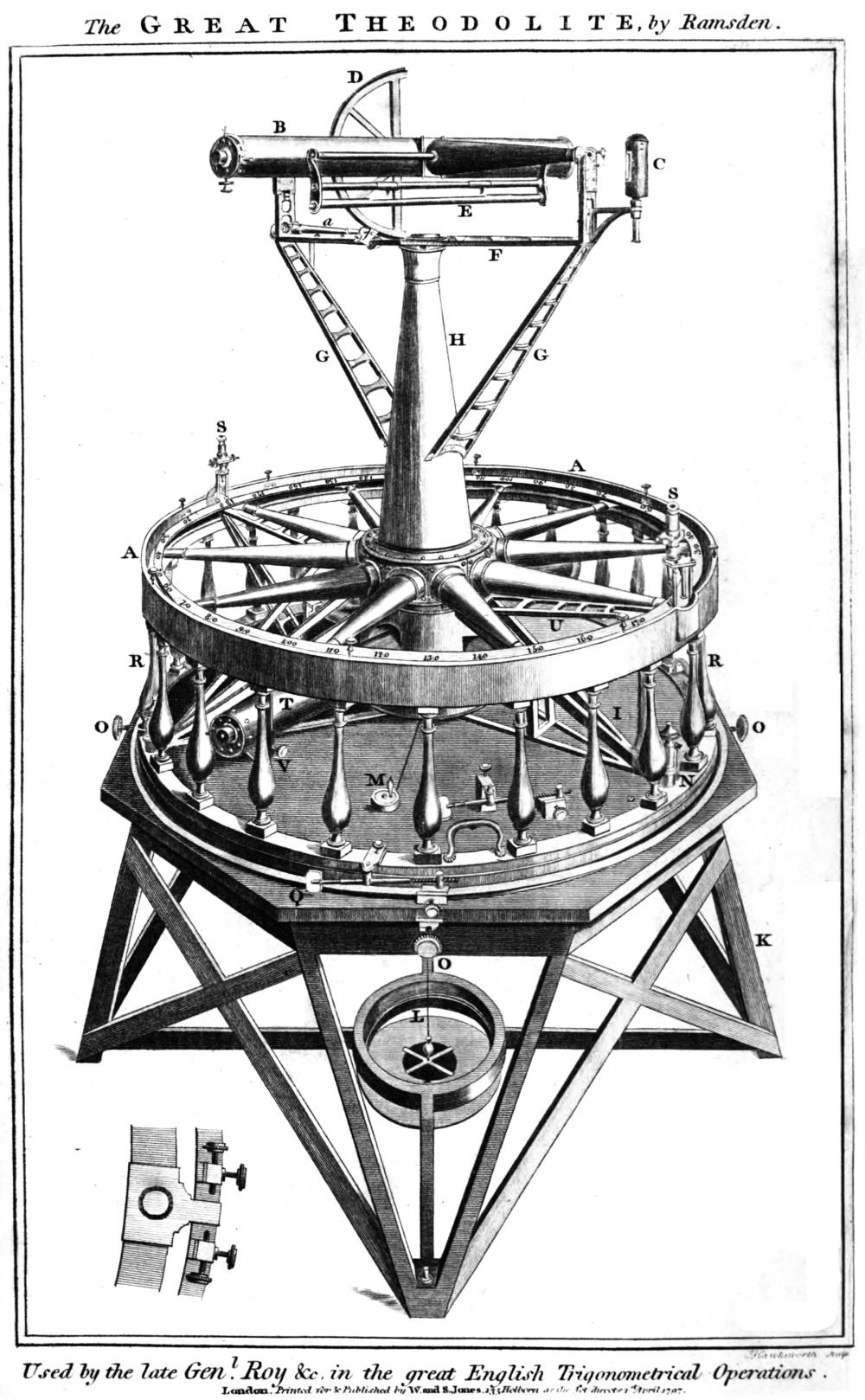

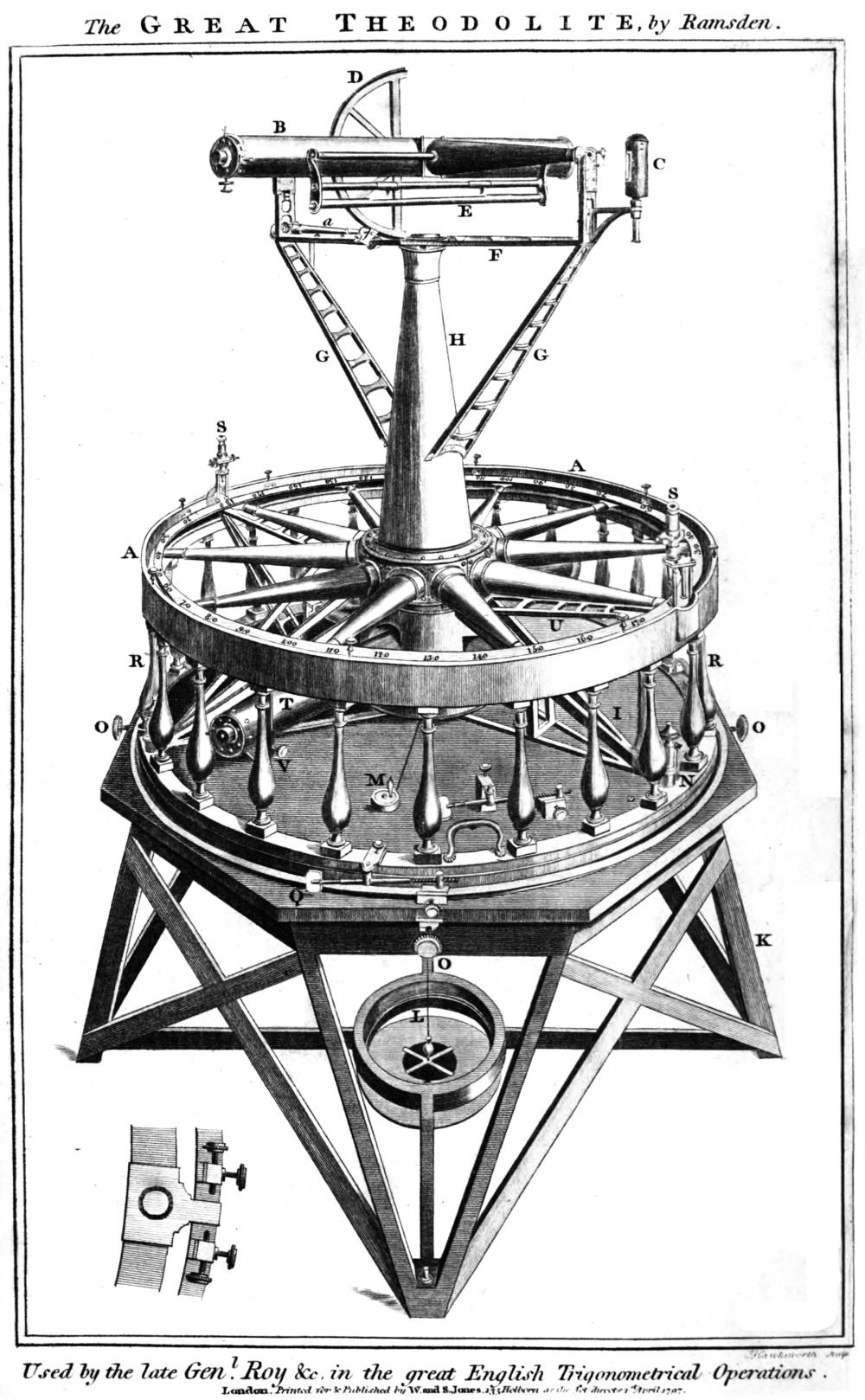

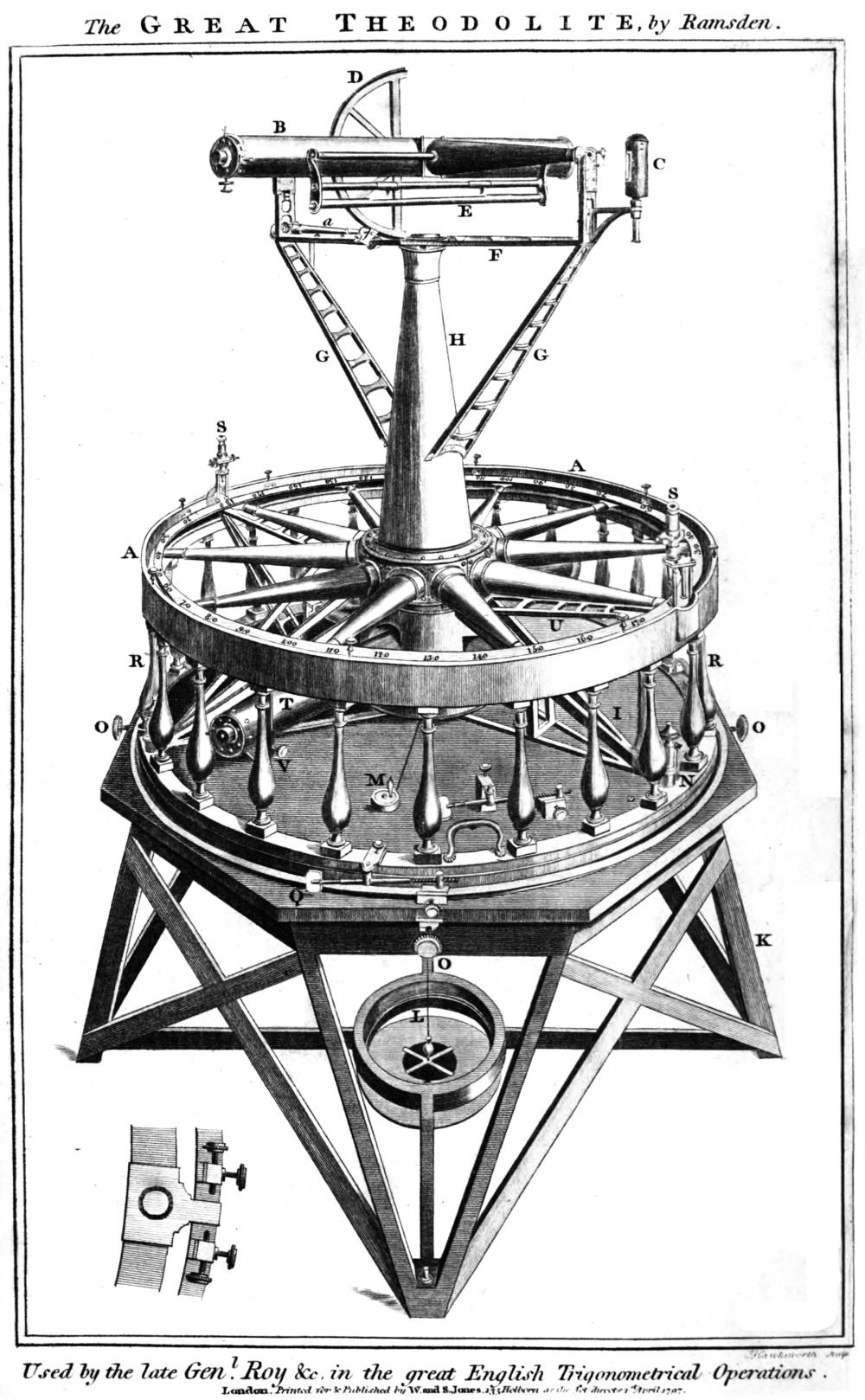

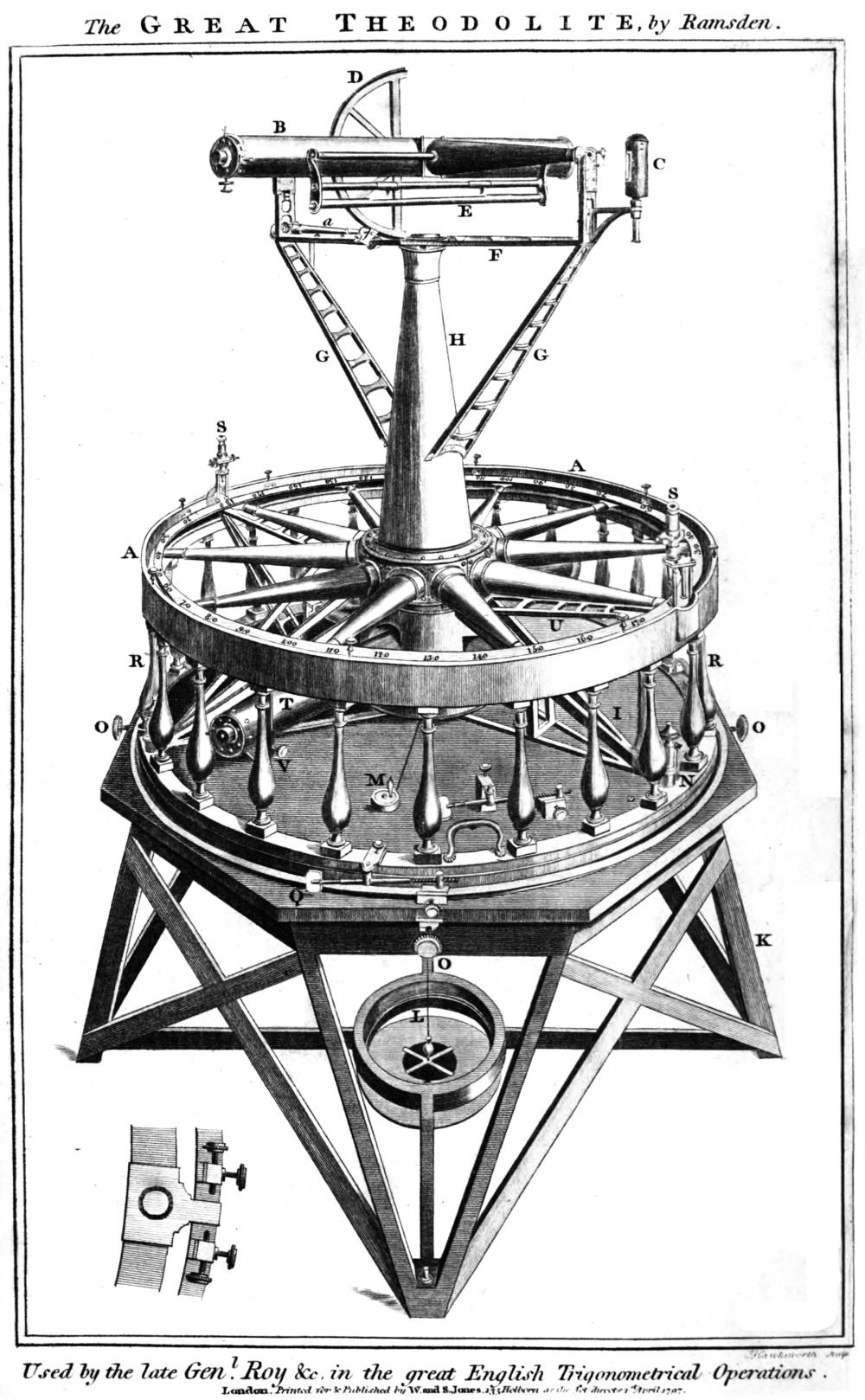

Fig. 2. Large Theodolite (engraving by Hawksworth), made by Jesse Ramsden, similar to the one made by William Cary which was used by Lambton during his surveying (Adams 1803, Wikipedia)

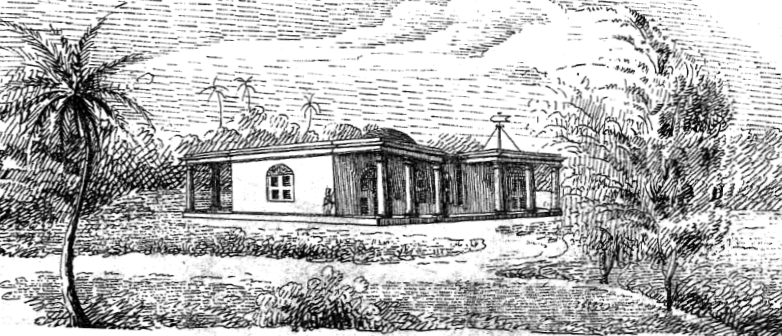

Since 1792, the Madras Observatory was moved to Nungambakkam in Madras and managed by the British East India Company in Madras (renamed as Chennai) -- in order to promote "the knowledge of astronomy, geography and navigation in India", the building was designed by Michael Topping (1747--1796), Chief Marine Surveyor of Fort St. George in Madras, founder of the oldest modern technical school outside Europe, College of Engineering since 1861. In 1788, he started surveying with a sextant.

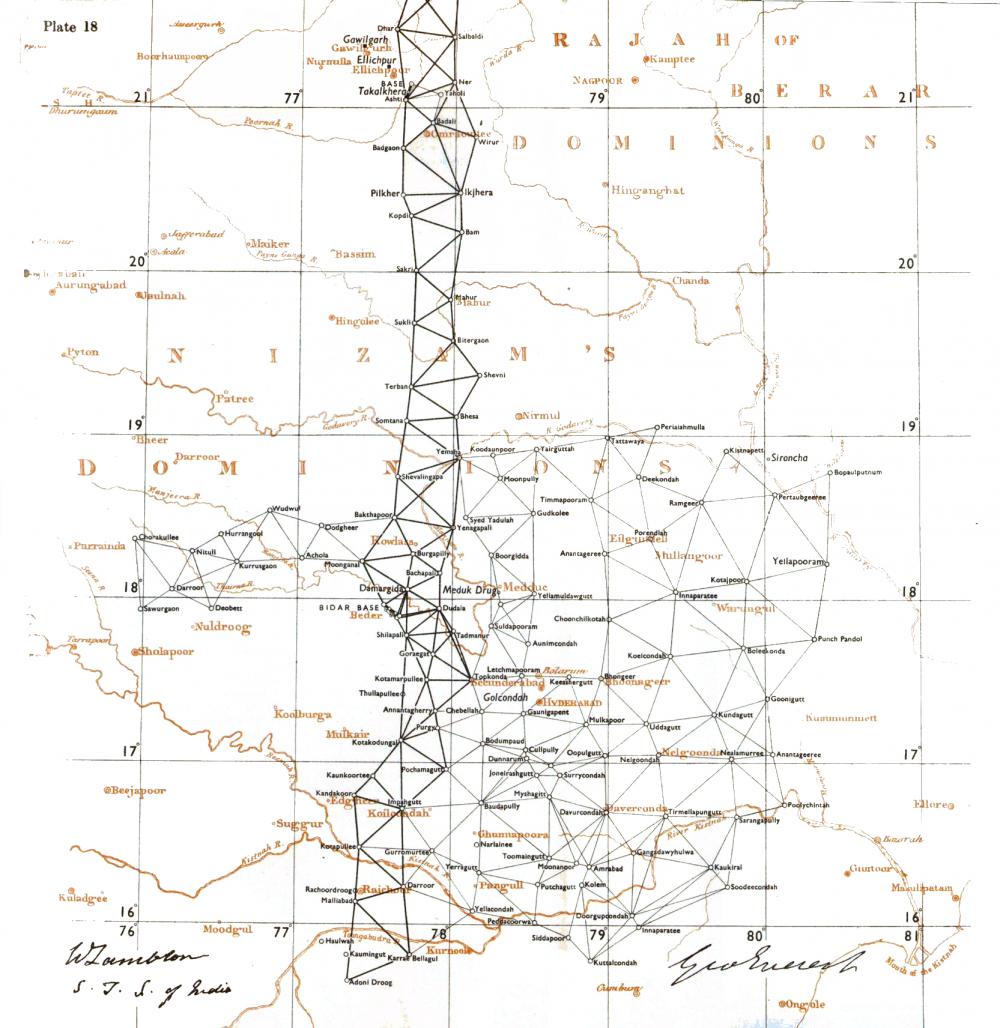

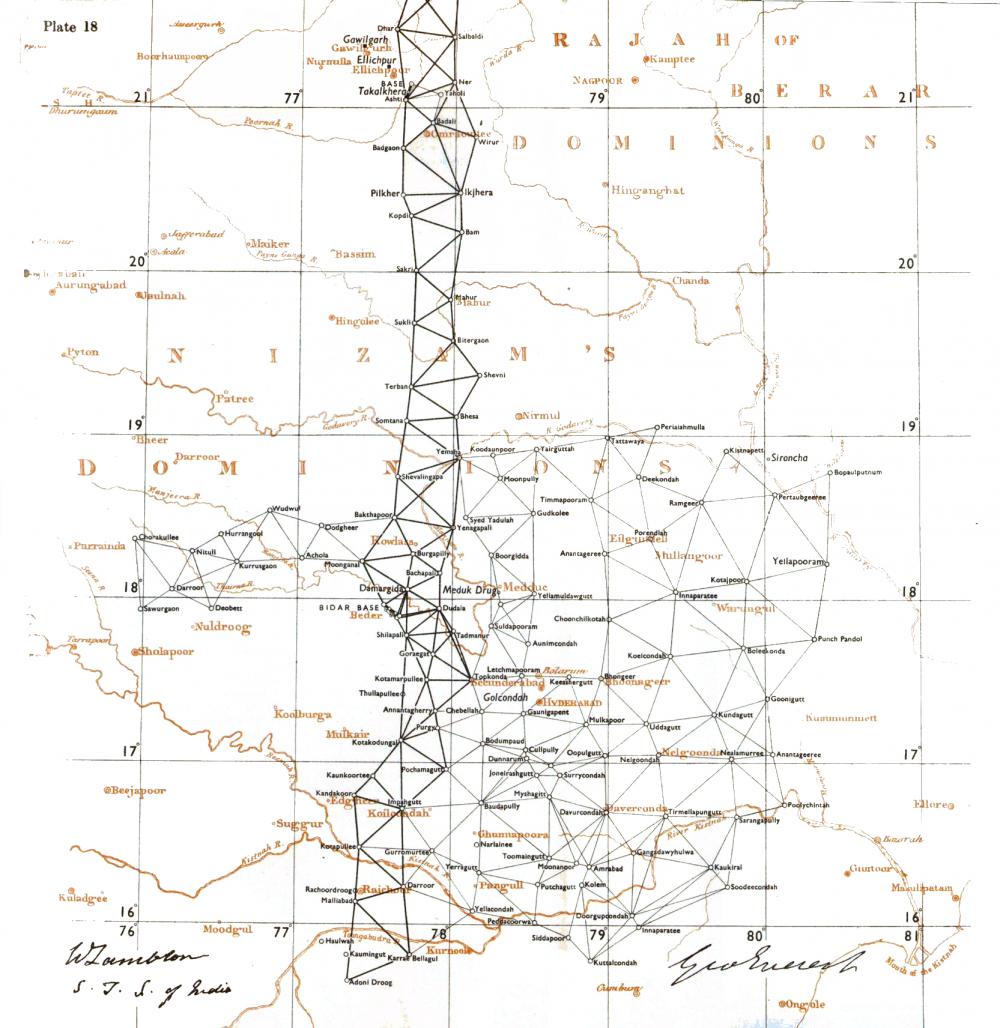

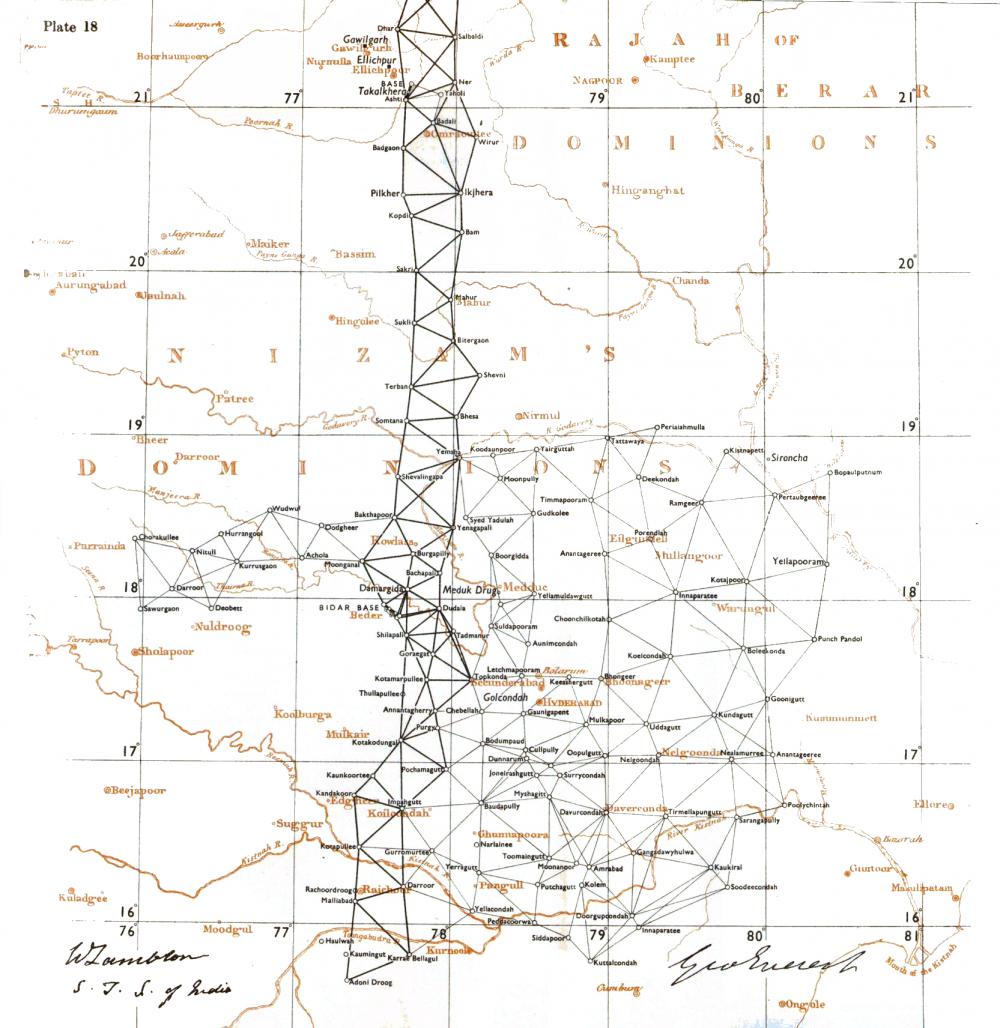

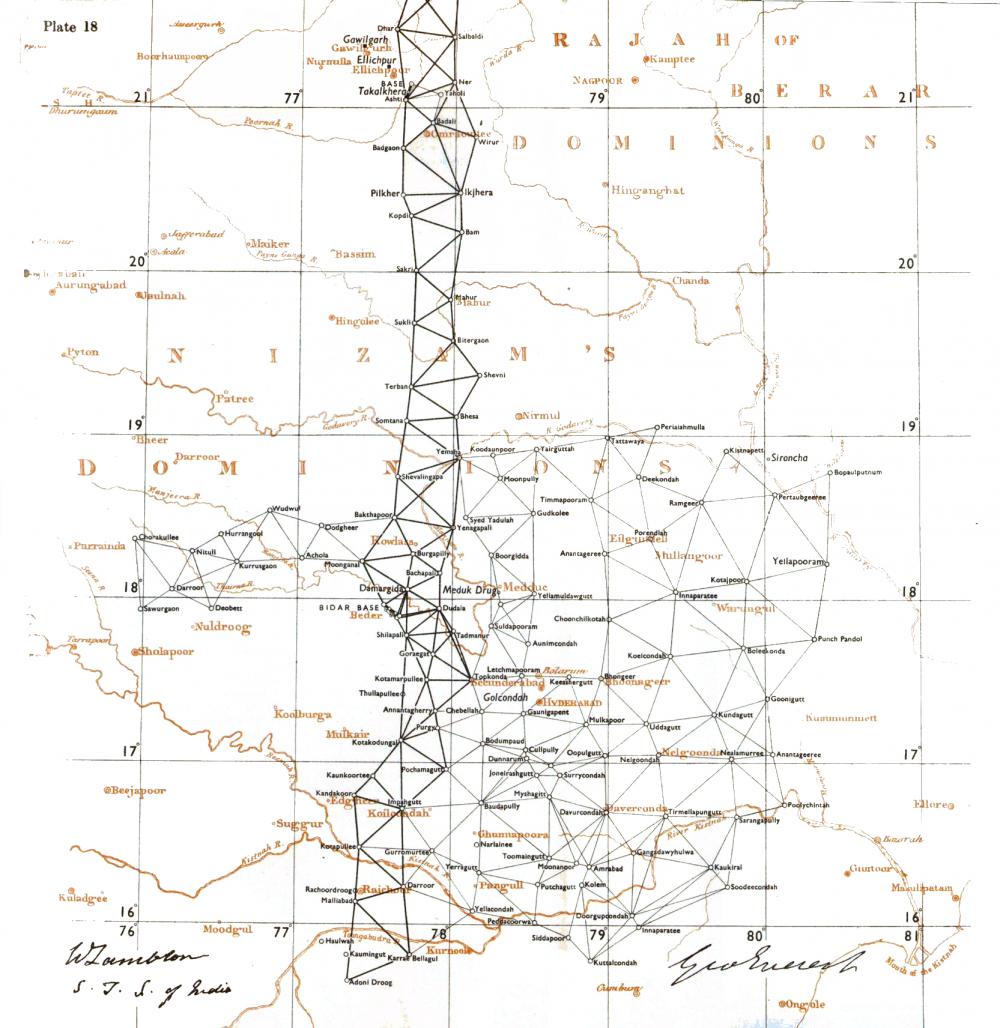

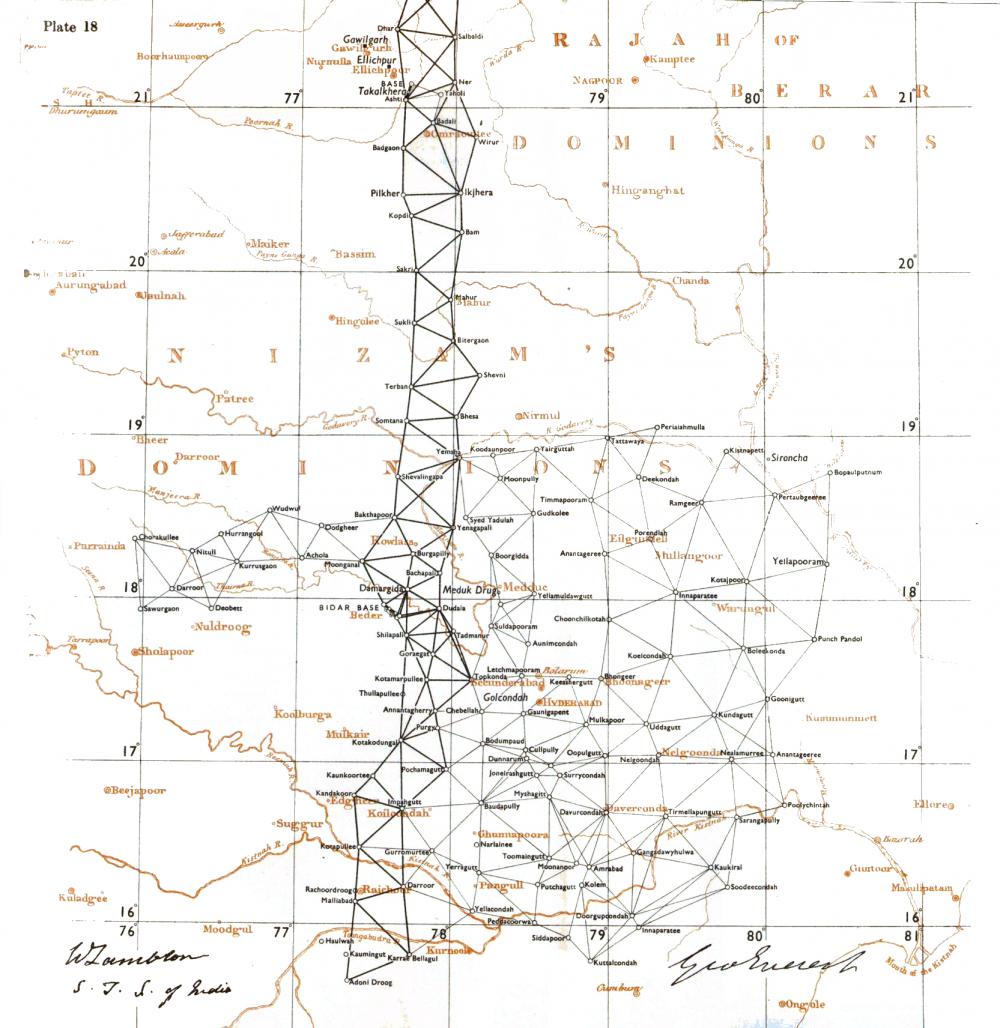

Fig. 3. Lambton & Everest triangulations in central India since 1800 (Wikipedia)

His large triangulation project across India was taken over later by Lieutenant-Colonel William Lambton, FRS (~1753--1823). The Great Trigonometrical Survey (GTS) of India started 1800.

Fig. 4. Madras Observatory in Chennai, designed by Michael Topping (1792), 1880 (Government of India, 1926)

For over a century the Madras Observatory was the only astronomical observatory in India.

In contrast to the Greenwich Observatory, which came into existence without any instruments, Madras had valuable instruments (20-inch transit and a 12-inch azimuth transit circle instrument, made by Troughton of London, observations since 1793) (Kochhar 2002). In contrast to Jaipur, large telescopes were used in Madras -- very rare in the Indian subcontinent.

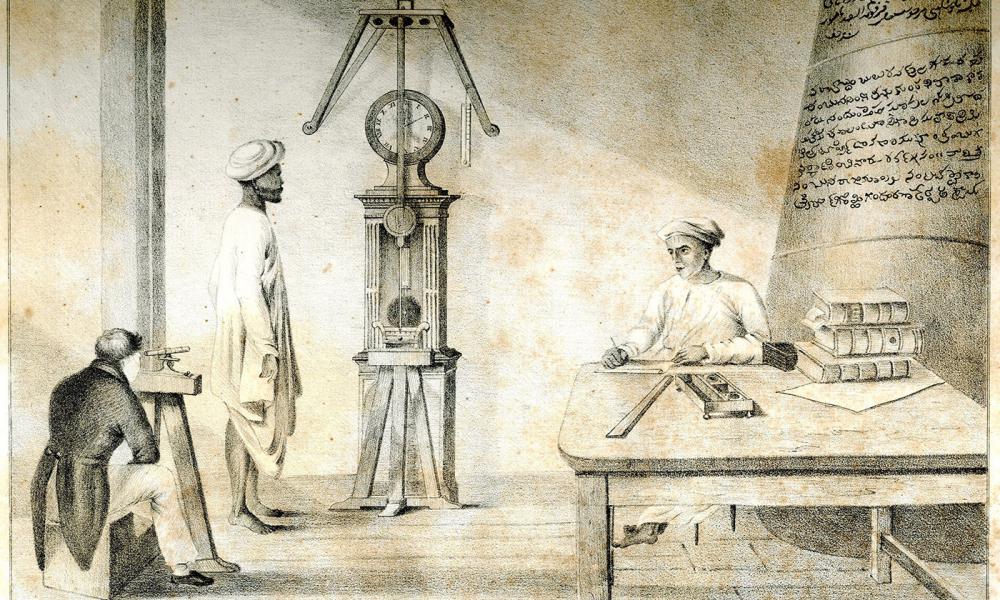

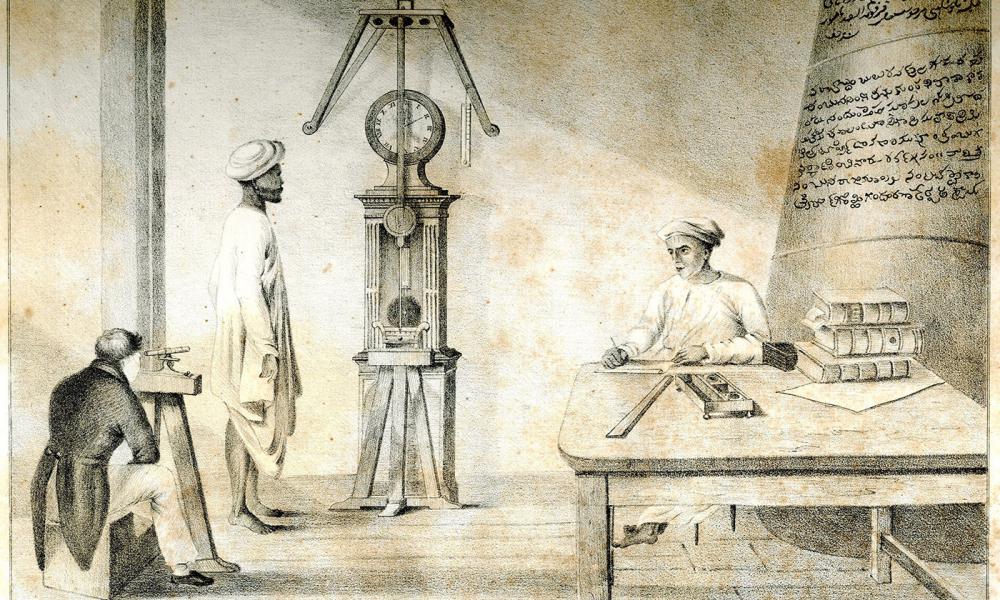

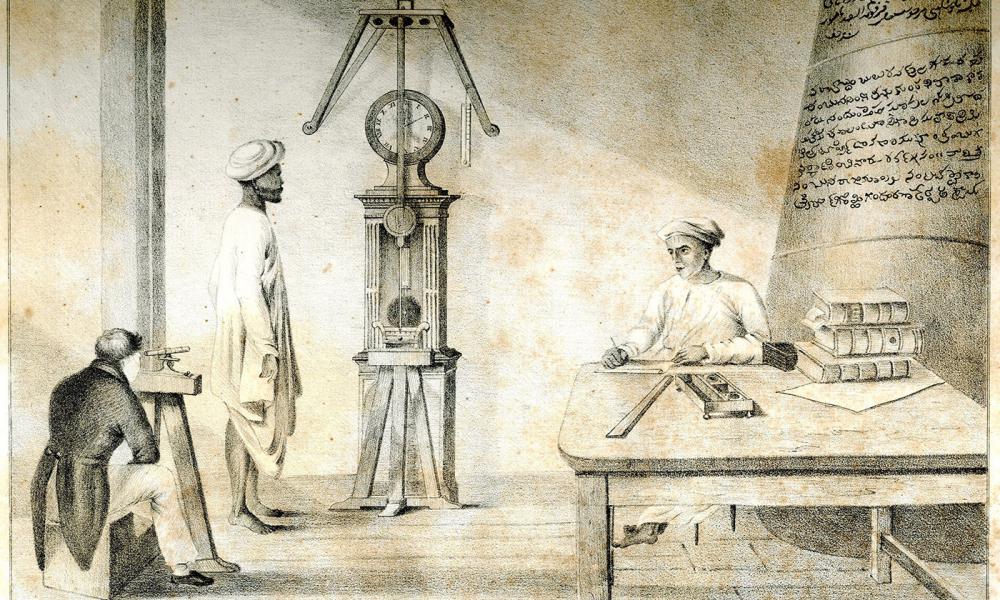

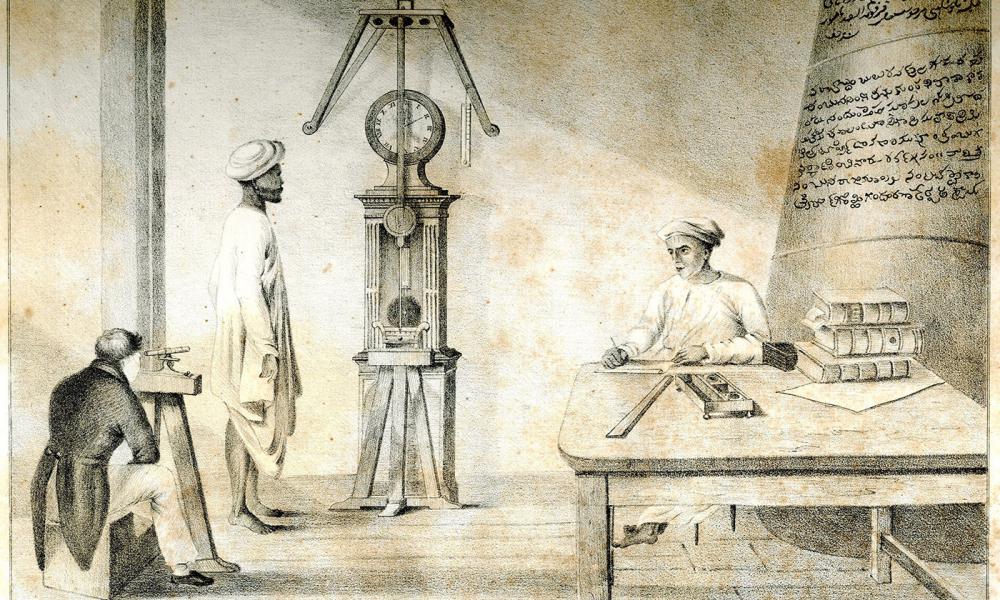

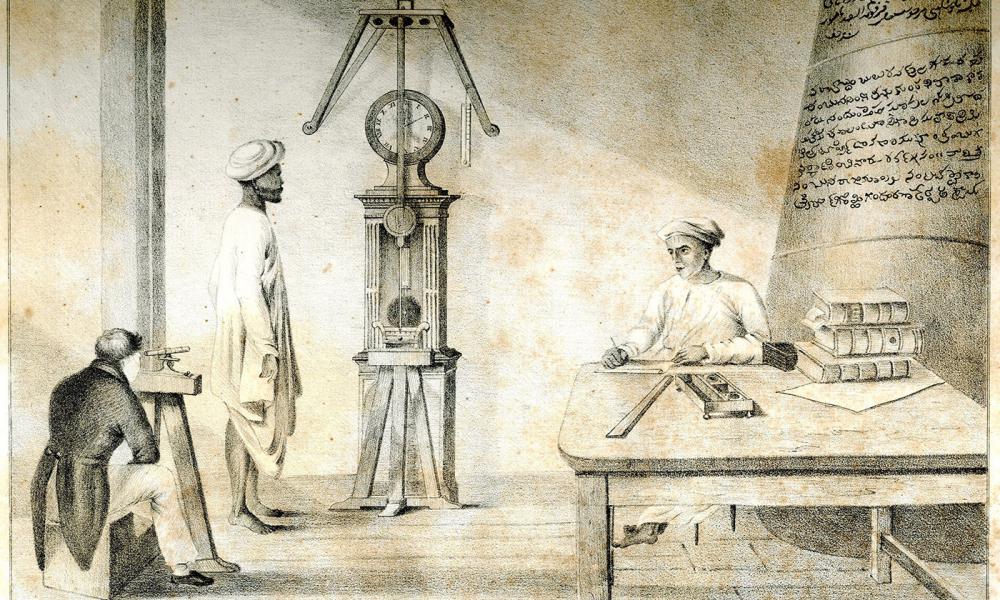

Fig. 5. John Goldingham (1767--1849) swinging a Kater’s pendulum, hung in front of a Haswell clock in Madras Observatory in 1821. The second assistant, Thiruvenkatachary, is reading the clock, while the first assistant, Srinivasachary, sitting near the 18-ft granite pier, is noting down the reading (Philosophical Transactions, 1822)

John Goldingham (1767--1849), 1796 to 1810 and 1812 to 1830, John Warren (1769--1830), Thomas Glanville Taylor (1804--1848), 1830 to 1848, and William Stephen Jacob (1813--1862), 1848 to 1859, were the successive Government Astronomers who dominated the activities at Madras.

Thomas Glanville Taylor published first "Results of Astronomical Observations Made at the Honorable the East India Companys Observatory at Madras, Vol. 1 for the Year 1831" (Madras 1832), then the "A General Catalogue of the Principal Fixed Stars from observations made at the Honorable, the East India Company’s Observatory at Madras in the Years 1830--1843, Vol. V" (Madras 1844).

In addition three solar eclipses (cf. Pang 2002, p. 16) were visible in India in 1868, 1871 and 1872, and in addition in 1874 the Transit of Venus. In 1868 the spectrum of prominences was observed; which led to the discovery of a bright yellow line (D3) near the sodium double lines as originating from the new element Helium.

Major James Francis Tennant (1829--1915) observed the total solar eclipse of 1868. He wanted to decide whether the prominances "are gaseous or consist of solid particles, whether they shine in their own light or in that of the Sun." Together with John Frederick William Herschel (1792--1871), Tennant was able to observe the solar eclipse (1868) from a station near Guntur. His attempt to photograph the corona was unsuccessful. However, he succeeded in observing a continuous spectrum of corona and emission lines in the spectrum of a prominance. Polariscope observations by other members of his group showed that the corona is not self-luminous, but reflects the light from the Sun’s surface. Tennant observed the solar eclipse (1871) in Doddabetta in the Nilgiri Mountains. Under his direction, spectroscopic observations were made, and photographs of the corona were obtained.

Tennant participated also in the Transit of Venus (1874) in Roorkee. He wanted to receive instruments from the Indian government, which could then be handed over to a solar observatory. Among other things, photographs of the important event were made.

Fig. 6. Madras Observatory (1880) (© IIA Archives, donated by Ms Cherry Armstrong, the great, great-grand daughter of Norman Pogson)

Madras Observatory is famous for the discovery of 58 asteroids and 21 variable stars. Norman Robert Pogson (1829--1891), director from 1860 to 1878, discovered 8 asteroids from 1856 to 1885, and 134 stars, 106 variable stars, 21 possible variable stars and 7 possible supernovae. His most famous contribution was the introduction of the logarithmic stellar magnitude system (1856): a first magnitude star is about 2.512 times as bright as a second magnitude star -- this fifth root of 100 is known as Pogson’s Ratio.

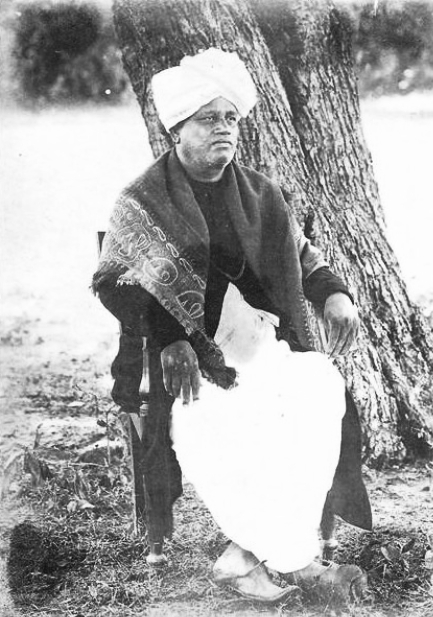

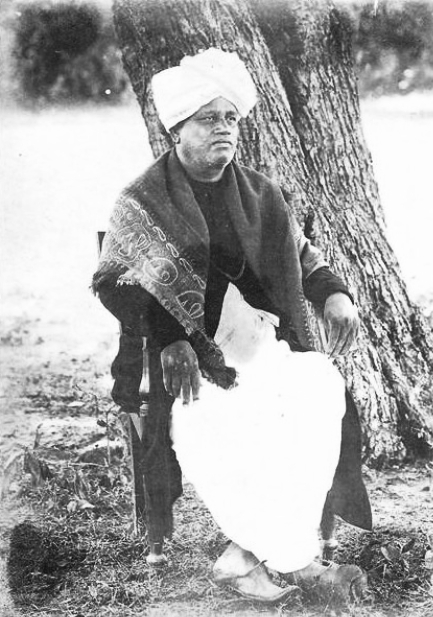

Pogson co-operated with the Indian astronomer Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary (1828--1880) since 1864. He determined the positions of stars for the Madras Star Catalogues. He also carried out observations of the total solar eclipses of 18 August 1868 (from Vunparthy, a village north of Kurnool) with Pogson, who made spectroscopic studies, and 12 December 1871 (from Avanashi, a town in Tamil Nadu province). In addition, he wrote a treatise on the Transit of Venus, observed on 9 December 1874. He noticed that a star, recorded at magnitude 8.5 by astronomer T. Moottooswamy Pillai with a with a meridian circle in February 1864, had become invisible by January 1866, but was picked up again by Chary on 16 January 1867. The discovery of the light variation of R Reticuli (Mira type variable star) by Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary in 1867 is perhaps the first astronomical discovery made by an Indian in modern times. Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1872 -- the first Indian to be elected to the RAS.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-06 01:10:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Instruments

- 20-inch Transit instrument, made by Troughton of London

- 12-inch Azimuth transit circle, made by Troughton of London

- 8-inch Equatorial, made by Cooke of London

- Transit circle, made by William Simms of London (1858)

- Vertical force magnetometer and declination magnetometer, about 1860

Major James Francis Tennant (1829--1915) was in charge of Madras Observatory, and magnetic observations were started using vertical force and declination magnetometers from 1859 to 1861.

In 1877 Joseph Norman Lockyer (1836--1920) suggested that the photoheliograph (cf. King’s Observatory, Kew), already in India, should be used for daily photography of the Sun; solar photography started at Dehra Dun in 1878. With a bigger photoheliograph in 1880 the work continued until 1925, when already Kodaikanal has overtaken these observations.

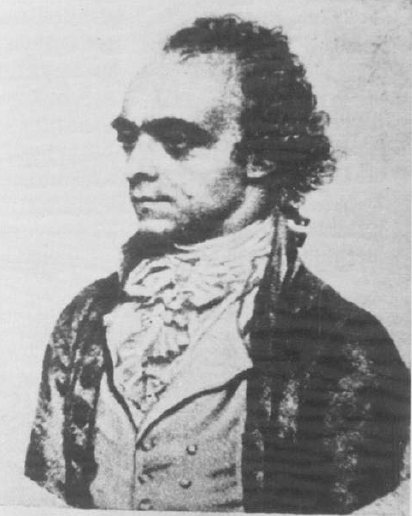

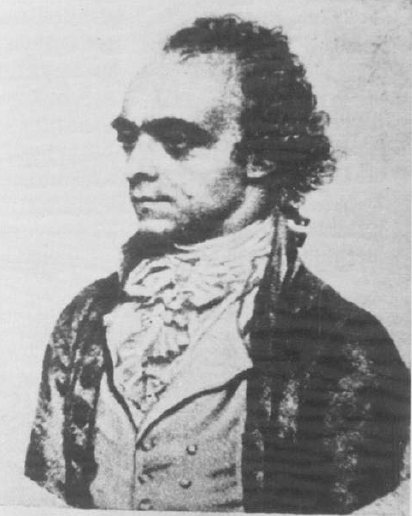

Fig. 7. Michael Topping (1747--1796) (Wikipedia)

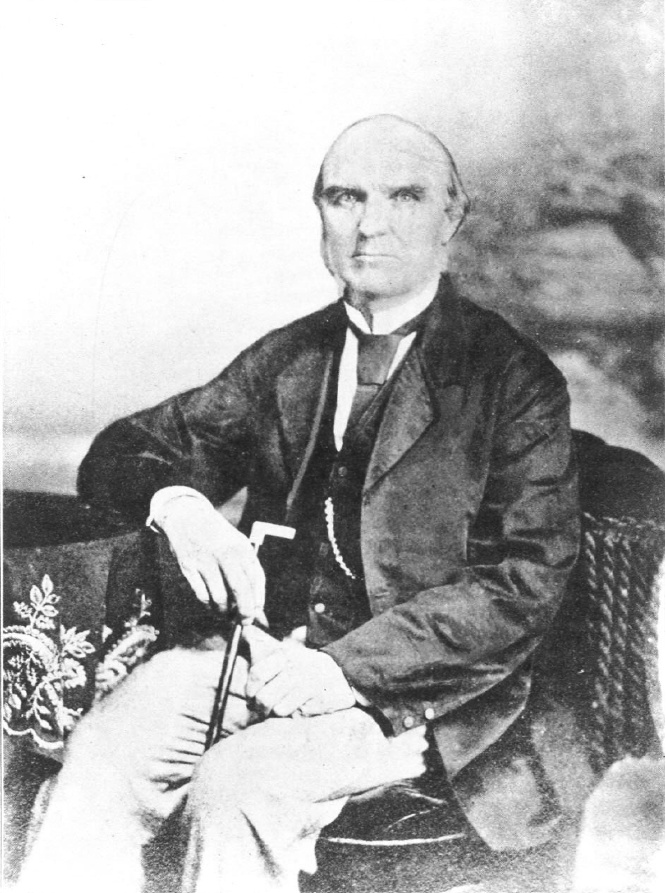

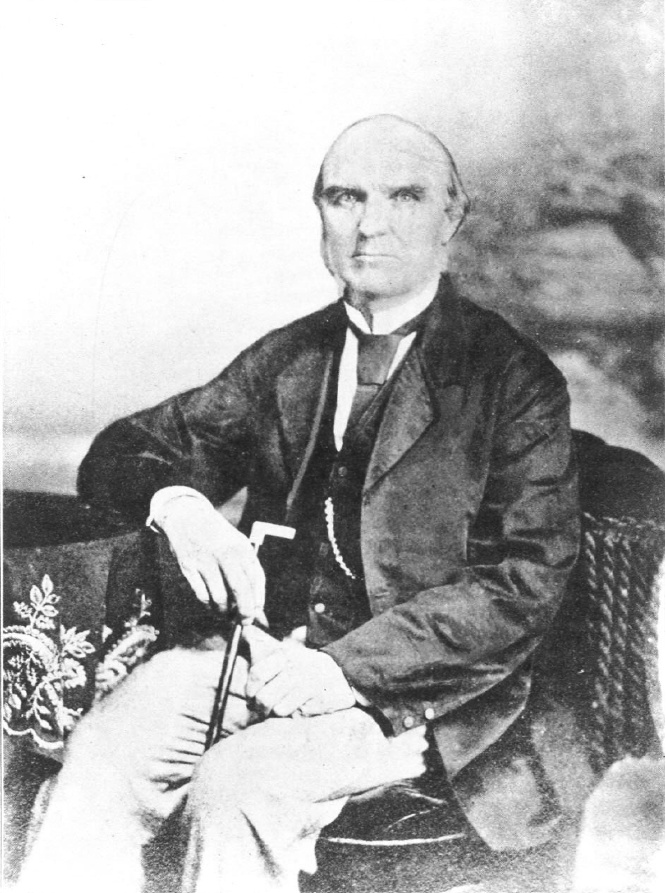

Fig. 8. John Goldingham (1767--1849) (Wikipedia)

Directors -- Government Astronomers

- William Petrie (1784--1816), 1786 to 1789

- Michael Topping (1747--1796), 1789 to 1796

- John Goldingham (1767--1849), 1796 to 1810 and 1812 to 1830

- John Warren (1769--1830), 1810 to 1812

- Thomas Glanville Taylor (1804--1848), 1830 to 1848

- William Stephen Jacob (1813--1862), 1848 to 1859

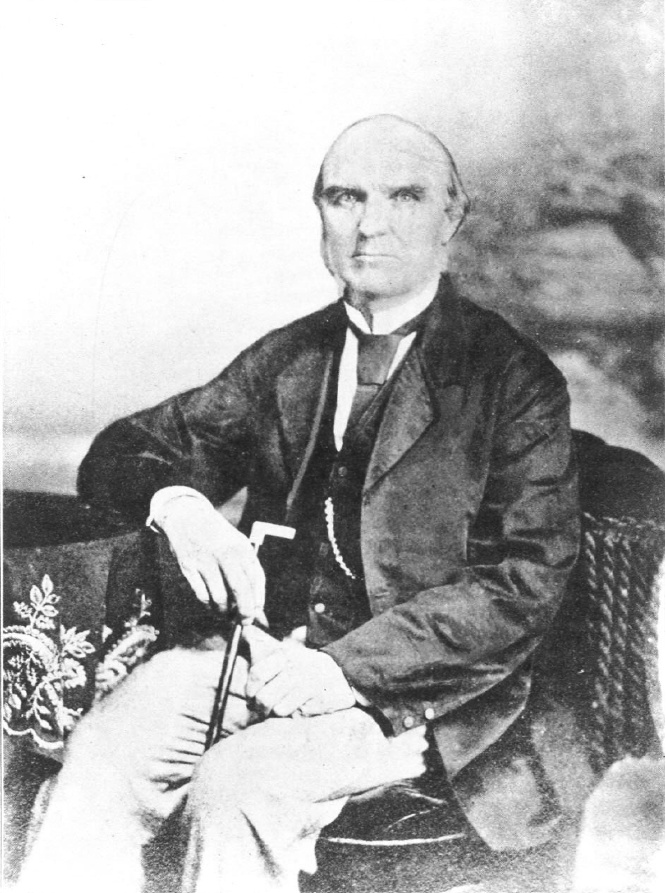

- Norman Robert Pogson (1829--1891), 1860 to 1878

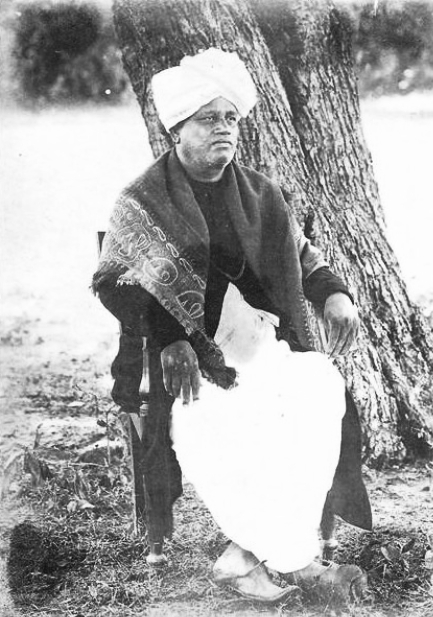

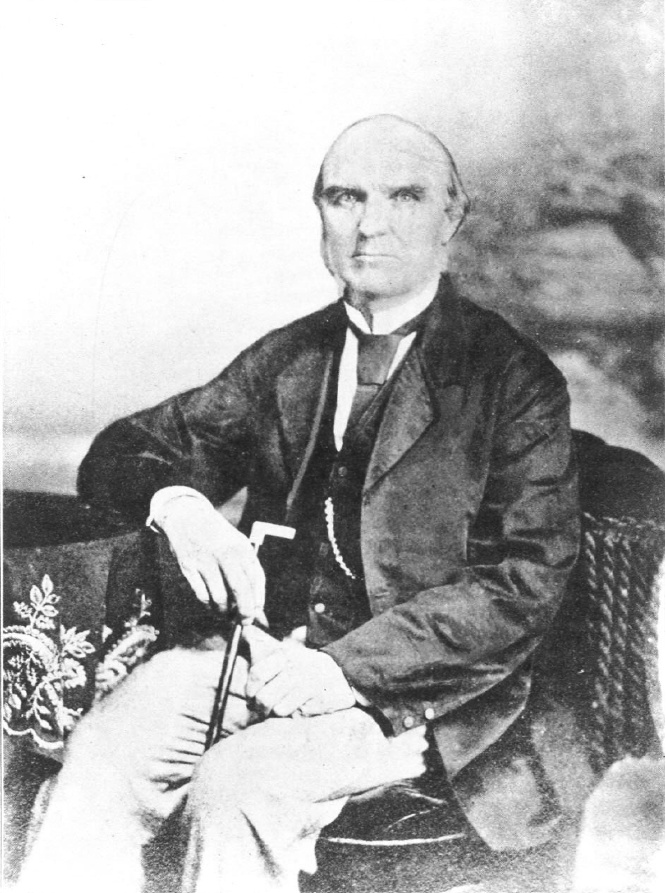

Fig. 9. Norman Robert Pogson (1829--1891) (Wikipedia)

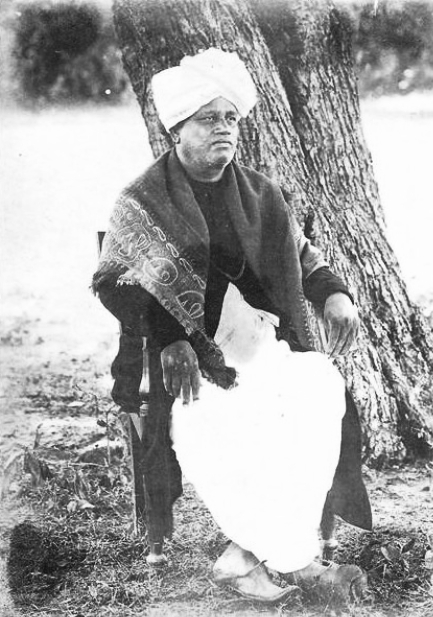

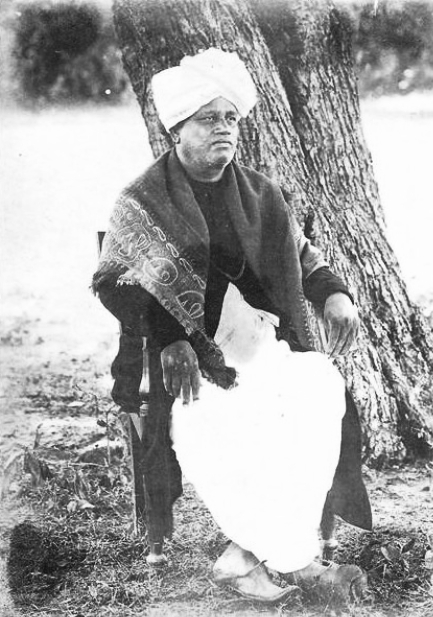

Fig. 10. Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary (1828--1880) (Wikipedia)

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:45:10

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

There are only ruins of the Madras Observatory of the 18th century, stone slabs and broken pillars -- not comparable to the famous Jaipur Observatory site of Jai Singh II.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:45:37

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

--

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:46:01

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no longer existing

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:46:25

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Madras Observatory later evolved into the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IAU Code 220), Kavalur.

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:46:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The successor of Madras Observatory is the famous Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IAU Code 220), Kavalur.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:47:22

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Adams, George: Geometrical and graphical essays, containing, a general description of the mathematical instruments used in geometry, civil and military surveying, levelling and perspective; with many new practical problems. London: W. Glendinning, sold by William & S. Jones 1803.

- Ansari, S.M. Razaullah: On Indian observatories in the 19th century. In: Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 36 (1975), p. 523-530.

- Edney, Matthew H.: Mapping an Empire: The Geographical Construction of British India, 1765-1843, Volume 10. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1997, p. 172-173.

- Government of India: Report on the Administration of the Meteorological Department of the Government of India in 1925-26, and a Note on the Long-Established Observatories of Madras and Bombay. Simla: Government of India Press 1926, p. 1-4.

- J. L. E. D.: Obituary: Pogson, N. R. In: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 52 (1892), p. 235.

- Jacob, W.S.: Notes on the Total Eclipse of the Sun of July 18, 1860 as observed in Spain. In: Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal 13 (1861), (1), p. 1-6.

- Jacob, W.S.: Meteorological Observations Made at the Honorable East India Company’s Observatory at Madras in the Years 1851-1855. Madras 1874.

- Jacob, W.S.: Magnetical observations made at the Honorable East India Company’s Observatory at Madras in the years 1851-1855. Madras Observatory 1884.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: Madras Observatory: the beginning. In: Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India 13 (1985a), p. 162-168.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: Madras Observatory -- buildings and instruments. In: Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India 13 (1985b), p. 287-302.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: The growth of modern astronomy in India, 1651--1960. In: Vistas in Astronomy 34 (1991), p. 69--105.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K. & J. Narlikar: Astronomy in India. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy 1995.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: Madras and Kodaikanal Observatories: A Brief History. In: RESONANCE (August 2002), p. 16-28.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K. & Wayne Orchiston: Chapter 24: The Development of Modern Astronomy and Emergence of Astrophysics in India. In: Nakamura, T. & Wayne Orchiston (ed.): The Emergence of Astrophysics in Asia: Opening a New Window on the Universe. Cham: Springer 2017.

(doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-62082-4_24).

- Lockyer, Joseph Norman: Contributions in Solar Physics. London: Macmillan 1874.

- McConnell, Anita: Taylor, Thomas Glanville (1804--1848). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press (doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27089).

- McConnell, Anita: Jacob, William Stephen. In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press (doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14576).

- Orchiston, W.; Lee, E-H. & Y.-S. Ahn: British Observations of the 18 August 1868 Total Solar Eclipse from Guntoor, India. In: Nakamura, T. & Wayne Orchiston (ed.): The Emergence of Astrophysics in Asia: Opening a New Window on the Universe. Cham: Springer 2017.

- Pang, Alex: Empire and the Sun: Victorian solar eclipse expeditions. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2002.

- Pogson, Norman Robert: Madras Meridian Circle Observations in 1862-64. Madras: Government of Madras 1887.

- Reddy, V.; Snedegar, K. & R.K. Balasubramanian: Scaling the magnitude: the fall and rise of N. R. Pogson. In: Journal of the British Astronomical Association 117 (2007), no. 5, p. 237-245.

- Shylaja, B.S.: Chintamani Ragoonatha Charry and Contemporary Indian Astronomy. Bangalore: Bangalore Association for Science Education and Navakarnataka Publications Private Limited 2012.

- Smith, Blake: How The Madras Observatory Heralded the Rise of Modern Astronomy in India. In: Aeon (https://www.thebetterindia.com/118431/madras-observatory-modern-astronomy-jantar-mantar-india/).

- Taylor, Thomas Glanville: Result of Astronomical Observations made at the Honorable, the East India Company’s Observatory at Madras, Volume IV. 1836--1837. Madras 1838.

- Tennant, James Francis: Report on the Total Eclipse of the Sun, August 17-18, 1868. In: Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society 37 (1869), p. 1-55.

- Tennant, James Francis: Report of observations of the total eclipse of the Sun on December 11-12, 1871, made by order of the Government of India, at Dodabetta, near Ootacamund. In: Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society 42 (1875c), p. 1-33.

- Topping, Michael: Description of an Astronomical Observatory erected at Madras in 1792 by Order of the East India Company, Madras, 24th December 1792. MS, Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives. Cambridge 1792.

- Topping, Michael: VI. Part of a letter from Mr. Michael Topping, to Mr. Tiberius Cavallo, F.R.S. In: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 82 (1792), p. 99-114.

- Udías, Agustin: Searching the Heavens and the Earth: The History of Jesuit Observatories. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic 2013.

- Vagiswari, A; Kameswara Rao, N; Birdie, C. & Priya Thakur: Michael Topping and the origin of the Madras Observatory. In: IIA Newsletter 14 (2009), 1, p. 16.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:47:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Smith, Blake: The Madras Observatory: from Jesuit cooperation to British rule

- Madras Observatory (Wikipedia)

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:34:45

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Madras Observatory, Madras (Chennai), Tamil Nadu, India

(today: Indian Institute of Astrophysics)

Location - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:35:39

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude 13°04’05’’ N, Longitude 80°14’48’’ E, Elevation 16m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-08-13 10:15:12

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

223

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-04 09:32:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Jesuit astronomers arrived at Jaipur in 1734, and established the longitude of several of Jai Singh II’s cities. The Jesuits studyed Sanskrit, in order to translate the greatest works of South Asian astronomy. Sawai Jai Singh II (1688--1743), Maharaja of Amber and Jaipur, was considerably interested in mathematics, architecture and astronomy; very famous are his five observatories in Jaipur, Dehli, Mathura (Agra province), Varanasi (Benares province), Ujjain (Malwa province) -- large sundials and calendar buildings in order to determine time and date, or to measure the altitude and azimuth of celestial objects. But Jai Singh II’s observatrories lacked telescopes, which had been invented in Europe a century before.

But the influence of the Jesuits in India was not very long. After Jai Singh II died, the time of the Jesuits came already to an end. Then the British East India Company dominated. For the East India Company in the 1780s two things were important: navigation (time keeping, also for getting the longitude) and land surveying. Later in 1860, also geomagnetism was included besides astronomy.

Fig. 1. Old Madras Observatory, Egmore in Madras (1786), woodcut (Taylor 1838), (Wikipedia)

Madras Observatory (1786) was one of the first modern observatories in Asia. William Petrie (1784--1816) started to establish Madras Observatory in 1786 as a private observatory, made of iron and timber. Petrie donated his instruments to the Madras Government before retiring to England.

Fig. 2. Large Theodolite (engraving by Hawksworth), made by Jesse Ramsden, similar to the one made by William Cary which was used by Lambton during his surveying (Adams 1803, Wikipedia)

Since 1792, the Madras Observatory was moved to Nungambakkam in Madras and managed by the British East India Company in Madras (renamed as Chennai) -- in order to promote "the knowledge of astronomy, geography and navigation in India", the building was designed by Michael Topping (1747--1796), Chief Marine Surveyor of Fort St. George in Madras, founder of the oldest modern technical school outside Europe, College of Engineering since 1861. In 1788, he started surveying with a sextant.

Fig. 3. Lambton & Everest triangulations in central India since 1800 (Wikipedia)

His large triangulation project across India was taken over later by Lieutenant-Colonel William Lambton, FRS (~1753--1823). The Great Trigonometrical Survey (GTS) of India started 1800.

Fig. 4. Madras Observatory in Chennai, designed by Michael Topping (1792), 1880 (Government of India, 1926)

For over a century the Madras Observatory was the only astronomical observatory in India.

In contrast to the Greenwich Observatory, which came into existence without any instruments, Madras had valuable instruments (20-inch transit and a 12-inch azimuth transit circle instrument, made by Troughton of London, observations since 1793) (Kochhar 2002). In contrast to Jaipur, large telescopes were used in Madras -- very rare in the Indian subcontinent.

Fig. 5. John Goldingham (1767--1849) swinging a Kater’s pendulum, hung in front of a Haswell clock in Madras Observatory in 1821. The second assistant, Thiruvenkatachary, is reading the clock, while the first assistant, Srinivasachary, sitting near the 18-ft granite pier, is noting down the reading (Philosophical Transactions, 1822)

John Goldingham (1767--1849), 1796 to 1810 and 1812 to 1830, John Warren (1769--1830), Thomas Glanville Taylor (1804--1848), 1830 to 1848, and William Stephen Jacob (1813--1862), 1848 to 1859, were the successive Government Astronomers who dominated the activities at Madras.

Thomas Glanville Taylor published first "Results of Astronomical Observations Made at the Honorable the East India Companys Observatory at Madras, Vol. 1 for the Year 1831" (Madras 1832), then the "A General Catalogue of the Principal Fixed Stars from observations made at the Honorable, the East India Company’s Observatory at Madras in the Years 1830--1843, Vol. V" (Madras 1844).

In addition three solar eclipses (cf. Pang 2002, p. 16) were visible in India in 1868, 1871 and 1872, and in addition in 1874 the Transit of Venus. In 1868 the spectrum of prominences was observed; which led to the discovery of a bright yellow line (D3) near the sodium double lines as originating from the new element Helium.

Major James Francis Tennant (1829--1915) observed the total solar eclipse of 1868. He wanted to decide whether the prominances "are gaseous or consist of solid particles, whether they shine in their own light or in that of the Sun." Together with John Frederick William Herschel (1792--1871), Tennant was able to observe the solar eclipse (1868) from a station near Guntur. His attempt to photograph the corona was unsuccessful. However, he succeeded in observing a continuous spectrum of corona and emission lines in the spectrum of a prominance. Polariscope observations by other members of his group showed that the corona is not self-luminous, but reflects the light from the Sun’s surface. Tennant observed the solar eclipse (1871) in Doddabetta in the Nilgiri Mountains. Under his direction, spectroscopic observations were made, and photographs of the corona were obtained.

Tennant participated also in the Transit of Venus (1874) in Roorkee. He wanted to receive instruments from the Indian government, which could then be handed over to a solar observatory. Among other things, photographs of the important event were made.

Fig. 6. Madras Observatory (1880) (© IIA Archives, donated by Ms Cherry Armstrong, the great, great-grand daughter of Norman Pogson)

Madras Observatory is famous for the discovery of 58 asteroids and 21 variable stars. Norman Robert Pogson (1829--1891), director from 1860 to 1878, discovered 8 asteroids from 1856 to 1885, and 134 stars, 106 variable stars, 21 possible variable stars and 7 possible supernovae. His most famous contribution was the introduction of the logarithmic stellar magnitude system (1856): a first magnitude star is about 2.512 times as bright as a second magnitude star -- this fifth root of 100 is known as Pogson’s Ratio.

Pogson co-operated with the Indian astronomer Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary (1828--1880) since 1864. He determined the positions of stars for the Madras Star Catalogues. He also carried out observations of the total solar eclipses of 18 August 1868 (from Vunparthy, a village north of Kurnool) with Pogson, who made spectroscopic studies, and 12 December 1871 (from Avanashi, a town in Tamil Nadu province). In addition, he wrote a treatise on the Transit of Venus, observed on 9 December 1874. He noticed that a star, recorded at magnitude 8.5 by astronomer T. Moottooswamy Pillai with a with a meridian circle in February 1864, had become invisible by January 1866, but was picked up again by Chary on 16 January 1867. The discovery of the light variation of R Reticuli (Mira type variable star) by Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary in 1867 is perhaps the first astronomical discovery made by an Indian in modern times. Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1872 -- the first Indian to be elected to the RAS.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-06 01:10:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Instruments

- 20-inch Transit instrument, made by Troughton of London

- 12-inch Azimuth transit circle, made by Troughton of London

- 8-inch Equatorial, made by Cooke of London

- Transit circle, made by William Simms of London (1858)

- Vertical force magnetometer and declination magnetometer, about 1860

Major James Francis Tennant (1829--1915) was in charge of Madras Observatory, and magnetic observations were started using vertical force and declination magnetometers from 1859 to 1861.

In 1877 Joseph Norman Lockyer (1836--1920) suggested that the photoheliograph (cf. King’s Observatory, Kew), already in India, should be used for daily photography of the Sun; solar photography started at Dehra Dun in 1878. With a bigger photoheliograph in 1880 the work continued until 1925, when already Kodaikanal has overtaken these observations.

Fig. 7. Michael Topping (1747--1796) (Wikipedia)

Fig. 8. John Goldingham (1767--1849) (Wikipedia)

Directors -- Government Astronomers

- William Petrie (1784--1816), 1786 to 1789

- Michael Topping (1747--1796), 1789 to 1796

- John Goldingham (1767--1849), 1796 to 1810 and 1812 to 1830

- John Warren (1769--1830), 1810 to 1812

- Thomas Glanville Taylor (1804--1848), 1830 to 1848

- William Stephen Jacob (1813--1862), 1848 to 1859

- Norman Robert Pogson (1829--1891), 1860 to 1878

Fig. 9. Norman Robert Pogson (1829--1891) (Wikipedia)

Fig. 10. Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary (1828--1880) (Wikipedia)

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:45:10

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

There are only ruins of the Madras Observatory of the 18th century, stone slabs and broken pillars -- not comparable to the famous Jaipur Observatory site of Jai Singh II.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:45:37

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

--

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:46:01

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no longer existing

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:46:25

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Madras Observatory later evolved into the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IAU Code 220), Kavalur.

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:46:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The successor of Madras Observatory is the famous Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IAU Code 220), Kavalur.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:47:22

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Adams, George: Geometrical and graphical essays, containing, a general description of the mathematical instruments used in geometry, civil and military surveying, levelling and perspective; with many new practical problems. London: W. Glendinning, sold by William & S. Jones 1803.

- Ansari, S.M. Razaullah: On Indian observatories in the 19th century. In: Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 36 (1975), p. 523-530.

- Edney, Matthew H.: Mapping an Empire: The Geographical Construction of British India, 1765-1843, Volume 10. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1997, p. 172-173.

- Government of India: Report on the Administration of the Meteorological Department of the Government of India in 1925-26, and a Note on the Long-Established Observatories of Madras and Bombay. Simla: Government of India Press 1926, p. 1-4.

- J. L. E. D.: Obituary: Pogson, N. R. In: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 52 (1892), p. 235.

- Jacob, W.S.: Notes on the Total Eclipse of the Sun of July 18, 1860 as observed in Spain. In: Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal 13 (1861), (1), p. 1-6.

- Jacob, W.S.: Meteorological Observations Made at the Honorable East India Company’s Observatory at Madras in the Years 1851-1855. Madras 1874.

- Jacob, W.S.: Magnetical observations made at the Honorable East India Company’s Observatory at Madras in the years 1851-1855. Madras Observatory 1884.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: Madras Observatory: the beginning. In: Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India 13 (1985a), p. 162-168.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: Madras Observatory -- buildings and instruments. In: Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India 13 (1985b), p. 287-302.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: The growth of modern astronomy in India, 1651--1960. In: Vistas in Astronomy 34 (1991), p. 69--105.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K. & J. Narlikar: Astronomy in India. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy 1995.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: Madras and Kodaikanal Observatories: A Brief History. In: RESONANCE (August 2002), p. 16-28.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K. & Wayne Orchiston: Chapter 24: The Development of Modern Astronomy and Emergence of Astrophysics in India. In: Nakamura, T. & Wayne Orchiston (ed.): The Emergence of Astrophysics in Asia: Opening a New Window on the Universe. Cham: Springer 2017.

(doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-62082-4_24).

- Lockyer, Joseph Norman: Contributions in Solar Physics. London: Macmillan 1874.

- McConnell, Anita: Taylor, Thomas Glanville (1804--1848). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press (doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27089).

- McConnell, Anita: Jacob, William Stephen. In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press (doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14576).

- Orchiston, W.; Lee, E-H. & Y.-S. Ahn: British Observations of the 18 August 1868 Total Solar Eclipse from Guntoor, India. In: Nakamura, T. & Wayne Orchiston (ed.): The Emergence of Astrophysics in Asia: Opening a New Window on the Universe. Cham: Springer 2017.

- Pang, Alex: Empire and the Sun: Victorian solar eclipse expeditions. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2002.

- Pogson, Norman Robert: Madras Meridian Circle Observations in 1862-64. Madras: Government of Madras 1887.

- Reddy, V.; Snedegar, K. & R.K. Balasubramanian: Scaling the magnitude: the fall and rise of N. R. Pogson. In: Journal of the British Astronomical Association 117 (2007), no. 5, p. 237-245.

- Shylaja, B.S.: Chintamani Ragoonatha Charry and Contemporary Indian Astronomy. Bangalore: Bangalore Association for Science Education and Navakarnataka Publications Private Limited 2012.

- Smith, Blake: How The Madras Observatory Heralded the Rise of Modern Astronomy in India. In: Aeon (https://www.thebetterindia.com/118431/madras-observatory-modern-astronomy-jantar-mantar-india/).

- Taylor, Thomas Glanville: Result of Astronomical Observations made at the Honorable, the East India Company’s Observatory at Madras, Volume IV. 1836--1837. Madras 1838.

- Tennant, James Francis: Report on the Total Eclipse of the Sun, August 17-18, 1868. In: Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society 37 (1869), p. 1-55.

- Tennant, James Francis: Report of observations of the total eclipse of the Sun on December 11-12, 1871, made by order of the Government of India, at Dodabetta, near Ootacamund. In: Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society 42 (1875c), p. 1-33.

- Topping, Michael: Description of an Astronomical Observatory erected at Madras in 1792 by Order of the East India Company, Madras, 24th December 1792. MS, Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives. Cambridge 1792.

- Topping, Michael: VI. Part of a letter from Mr. Michael Topping, to Mr. Tiberius Cavallo, F.R.S. In: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 82 (1792), p. 99-114.

- Udías, Agustin: Searching the Heavens and the Earth: The History of Jesuit Observatories. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic 2013.

- Vagiswari, A; Kameswara Rao, N; Birdie, C. & Priya Thakur: Michael Topping and the origin of the Madras Observatory. In: IIA Newsletter 14 (2009), 1, p. 16.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:47:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Smith, Blake: The Madras Observatory: from Jesuit cooperation to British rule

- Madras Observatory (Wikipedia)

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:35:39

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude 13°04’05’’ N, Longitude 80°14’48’’ E, Elevation 16m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-08-13 10:15:12

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

223

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-04 09:32:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Jesuit astronomers arrived at Jaipur in 1734, and established the longitude of several of Jai Singh II’s cities. The Jesuits studyed Sanskrit, in order to translate the greatest works of South Asian astronomy. Sawai Jai Singh II (1688--1743), Maharaja of Amber and Jaipur, was considerably interested in mathematics, architecture and astronomy; very famous are his five observatories in Jaipur, Dehli, Mathura (Agra province), Varanasi (Benares province), Ujjain (Malwa province) -- large sundials and calendar buildings in order to determine time and date, or to measure the altitude and azimuth of celestial objects. But Jai Singh II’s observatrories lacked telescopes, which had been invented in Europe a century before.

But the influence of the Jesuits in India was not very long. After Jai Singh II died, the time of the Jesuits came already to an end. Then the British East India Company dominated. For the East India Company in the 1780s two things were important: navigation (time keeping, also for getting the longitude) and land surveying. Later in 1860, also geomagnetism was included besides astronomy.

Fig. 1. Old Madras Observatory, Egmore in Madras (1786), woodcut (Taylor 1838), (Wikipedia)

Madras Observatory (1786) was one of the first modern observatories in Asia. William Petrie (1784--1816) started to establish Madras Observatory in 1786 as a private observatory, made of iron and timber. Petrie donated his instruments to the Madras Government before retiring to England.

Fig. 2. Large Theodolite (engraving by Hawksworth), made by Jesse Ramsden, similar to the one made by William Cary which was used by Lambton during his surveying (Adams 1803, Wikipedia)

Since 1792, the Madras Observatory was moved to Nungambakkam in Madras and managed by the British East India Company in Madras (renamed as Chennai) -- in order to promote "the knowledge of astronomy, geography and navigation in India", the building was designed by Michael Topping (1747--1796), Chief Marine Surveyor of Fort St. George in Madras, founder of the oldest modern technical school outside Europe, College of Engineering since 1861. In 1788, he started surveying with a sextant.

Fig. 3. Lambton & Everest triangulations in central India since 1800 (Wikipedia)

His large triangulation project across India was taken over later by Lieutenant-Colonel William Lambton, FRS (~1753--1823). The Great Trigonometrical Survey (GTS) of India started 1800.

Fig. 4. Madras Observatory in Chennai, designed by Michael Topping (1792), 1880 (Government of India, 1926)

For over a century the Madras Observatory was the only astronomical observatory in India.

In contrast to the Greenwich Observatory, which came into existence without any instruments, Madras had valuable instruments (20-inch transit and a 12-inch azimuth transit circle instrument, made by Troughton of London, observations since 1793) (Kochhar 2002). In contrast to Jaipur, large telescopes were used in Madras -- very rare in the Indian subcontinent.

Fig. 5. John Goldingham (1767--1849) swinging a Kater’s pendulum, hung in front of a Haswell clock in Madras Observatory in 1821. The second assistant, Thiruvenkatachary, is reading the clock, while the first assistant, Srinivasachary, sitting near the 18-ft granite pier, is noting down the reading (Philosophical Transactions, 1822)

John Goldingham (1767--1849), 1796 to 1810 and 1812 to 1830, John Warren (1769--1830), Thomas Glanville Taylor (1804--1848), 1830 to 1848, and William Stephen Jacob (1813--1862), 1848 to 1859, were the successive Government Astronomers who dominated the activities at Madras.

Thomas Glanville Taylor published first "Results of Astronomical Observations Made at the Honorable the East India Companys Observatory at Madras, Vol. 1 for the Year 1831" (Madras 1832), then the "A General Catalogue of the Principal Fixed Stars from observations made at the Honorable, the East India Company’s Observatory at Madras in the Years 1830--1843, Vol. V" (Madras 1844).

In addition three solar eclipses (cf. Pang 2002, p. 16) were visible in India in 1868, 1871 and 1872, and in addition in 1874 the Transit of Venus. In 1868 the spectrum of prominences was observed; which led to the discovery of a bright yellow line (D3) near the sodium double lines as originating from the new element Helium.

Major James Francis Tennant (1829--1915) observed the total solar eclipse of 1868. He wanted to decide whether the prominances "are gaseous or consist of solid particles, whether they shine in their own light or in that of the Sun." Together with John Frederick William Herschel (1792--1871), Tennant was able to observe the solar eclipse (1868) from a station near Guntur. His attempt to photograph the corona was unsuccessful. However, he succeeded in observing a continuous spectrum of corona and emission lines in the spectrum of a prominance. Polariscope observations by other members of his group showed that the corona is not self-luminous, but reflects the light from the Sun’s surface. Tennant observed the solar eclipse (1871) in Doddabetta in the Nilgiri Mountains. Under his direction, spectroscopic observations were made, and photographs of the corona were obtained.

Tennant participated also in the Transit of Venus (1874) in Roorkee. He wanted to receive instruments from the Indian government, which could then be handed over to a solar observatory. Among other things, photographs of the important event were made.

Fig. 6. Madras Observatory (1880) (© IIA Archives, donated by Ms Cherry Armstrong, the great, great-grand daughter of Norman Pogson)

Madras Observatory is famous for the discovery of 58 asteroids and 21 variable stars. Norman Robert Pogson (1829--1891), director from 1860 to 1878, discovered 8 asteroids from 1856 to 1885, and 134 stars, 106 variable stars, 21 possible variable stars and 7 possible supernovae. His most famous contribution was the introduction of the logarithmic stellar magnitude system (1856): a first magnitude star is about 2.512 times as bright as a second magnitude star -- this fifth root of 100 is known as Pogson’s Ratio.

Pogson co-operated with the Indian astronomer Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary (1828--1880) since 1864. He determined the positions of stars for the Madras Star Catalogues. He also carried out observations of the total solar eclipses of 18 August 1868 (from Vunparthy, a village north of Kurnool) with Pogson, who made spectroscopic studies, and 12 December 1871 (from Avanashi, a town in Tamil Nadu province). In addition, he wrote a treatise on the Transit of Venus, observed on 9 December 1874. He noticed that a star, recorded at magnitude 8.5 by astronomer T. Moottooswamy Pillai with a with a meridian circle in February 1864, had become invisible by January 1866, but was picked up again by Chary on 16 January 1867. The discovery of the light variation of R Reticuli (Mira type variable star) by Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary in 1867 is perhaps the first astronomical discovery made by an Indian in modern times. Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1872 -- the first Indian to be elected to the RAS.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-06 01:10:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Instruments

- 20-inch Transit instrument, made by Troughton of London

- 12-inch Azimuth transit circle, made by Troughton of London

- 8-inch Equatorial, made by Cooke of London

- Transit circle, made by William Simms of London (1858)

- Vertical force magnetometer and declination magnetometer, about 1860

Major James Francis Tennant (1829--1915) was in charge of Madras Observatory, and magnetic observations were started using vertical force and declination magnetometers from 1859 to 1861.

In 1877 Joseph Norman Lockyer (1836--1920) suggested that the photoheliograph (cf. King’s Observatory, Kew), already in India, should be used for daily photography of the Sun; solar photography started at Dehra Dun in 1878. With a bigger photoheliograph in 1880 the work continued until 1925, when already Kodaikanal has overtaken these observations.

Fig. 7. Michael Topping (1747--1796) (Wikipedia)

Fig. 8. John Goldingham (1767--1849) (Wikipedia)

Directors -- Government Astronomers

- William Petrie (1784--1816), 1786 to 1789

- Michael Topping (1747--1796), 1789 to 1796

- John Goldingham (1767--1849), 1796 to 1810 and 1812 to 1830

- John Warren (1769--1830), 1810 to 1812

- Thomas Glanville Taylor (1804--1848), 1830 to 1848

- William Stephen Jacob (1813--1862), 1848 to 1859

- Norman Robert Pogson (1829--1891), 1860 to 1878

Fig. 9. Norman Robert Pogson (1829--1891) (Wikipedia)

Fig. 10. Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary (1828--1880) (Wikipedia)

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:45:10

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

There are only ruins of the Madras Observatory of the 18th century, stone slabs and broken pillars -- not comparable to the famous Jaipur Observatory site of Jai Singh II.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:45:37

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

--

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:46:01

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no longer existing

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:46:25

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Madras Observatory later evolved into the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IAU Code 220), Kavalur.

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:46:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The successor of Madras Observatory is the famous Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IAU Code 220), Kavalur.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:47:22

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Adams, George: Geometrical and graphical essays, containing, a general description of the mathematical instruments used in geometry, civil and military surveying, levelling and perspective; with many new practical problems. London: W. Glendinning, sold by William & S. Jones 1803.

- Ansari, S.M. Razaullah: On Indian observatories in the 19th century. In: Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 36 (1975), p. 523-530.

- Edney, Matthew H.: Mapping an Empire: The Geographical Construction of British India, 1765-1843, Volume 10. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1997, p. 172-173.

- Government of India: Report on the Administration of the Meteorological Department of the Government of India in 1925-26, and a Note on the Long-Established Observatories of Madras and Bombay. Simla: Government of India Press 1926, p. 1-4.

- J. L. E. D.: Obituary: Pogson, N. R. In: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 52 (1892), p. 235.

- Jacob, W.S.: Notes on the Total Eclipse of the Sun of July 18, 1860 as observed in Spain. In: Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal 13 (1861), (1), p. 1-6.

- Jacob, W.S.: Meteorological Observations Made at the Honorable East India Company’s Observatory at Madras in the Years 1851-1855. Madras 1874.

- Jacob, W.S.: Magnetical observations made at the Honorable East India Company’s Observatory at Madras in the years 1851-1855. Madras Observatory 1884.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: Madras Observatory: the beginning. In: Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India 13 (1985a), p. 162-168.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: Madras Observatory -- buildings and instruments. In: Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India 13 (1985b), p. 287-302.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: The growth of modern astronomy in India, 1651--1960. In: Vistas in Astronomy 34 (1991), p. 69--105.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K. & J. Narlikar: Astronomy in India. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy 1995.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: Madras and Kodaikanal Observatories: A Brief History. In: RESONANCE (August 2002), p. 16-28.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K. & Wayne Orchiston: Chapter 24: The Development of Modern Astronomy and Emergence of Astrophysics in India. In: Nakamura, T. & Wayne Orchiston (ed.): The Emergence of Astrophysics in Asia: Opening a New Window on the Universe. Cham: Springer 2017.

(doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-62082-4_24).

- Lockyer, Joseph Norman: Contributions in Solar Physics. London: Macmillan 1874.

- McConnell, Anita: Taylor, Thomas Glanville (1804--1848). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press (doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27089).

- McConnell, Anita: Jacob, William Stephen. In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press (doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14576).

- Orchiston, W.; Lee, E-H. & Y.-S. Ahn: British Observations of the 18 August 1868 Total Solar Eclipse from Guntoor, India. In: Nakamura, T. & Wayne Orchiston (ed.): The Emergence of Astrophysics in Asia: Opening a New Window on the Universe. Cham: Springer 2017.

- Pang, Alex: Empire and the Sun: Victorian solar eclipse expeditions. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2002.

- Pogson, Norman Robert: Madras Meridian Circle Observations in 1862-64. Madras: Government of Madras 1887.

- Reddy, V.; Snedegar, K. & R.K. Balasubramanian: Scaling the magnitude: the fall and rise of N. R. Pogson. In: Journal of the British Astronomical Association 117 (2007), no. 5, p. 237-245.

- Shylaja, B.S.: Chintamani Ragoonatha Charry and Contemporary Indian Astronomy. Bangalore: Bangalore Association for Science Education and Navakarnataka Publications Private Limited 2012.

- Smith, Blake: How The Madras Observatory Heralded the Rise of Modern Astronomy in India. In: Aeon (https://www.thebetterindia.com/118431/madras-observatory-modern-astronomy-jantar-mantar-india/).

- Taylor, Thomas Glanville: Result of Astronomical Observations made at the Honorable, the East India Company’s Observatory at Madras, Volume IV. 1836--1837. Madras 1838.

- Tennant, James Francis: Report on the Total Eclipse of the Sun, August 17-18, 1868. In: Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society 37 (1869), p. 1-55.

- Tennant, James Francis: Report of observations of the total eclipse of the Sun on December 11-12, 1871, made by order of the Government of India, at Dodabetta, near Ootacamund. In: Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society 42 (1875c), p. 1-33.

- Topping, Michael: Description of an Astronomical Observatory erected at Madras in 1792 by Order of the East India Company, Madras, 24th December 1792. MS, Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives. Cambridge 1792.

- Topping, Michael: VI. Part of a letter from Mr. Michael Topping, to Mr. Tiberius Cavallo, F.R.S. In: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 82 (1792), p. 99-114.

- Udías, Agustin: Searching the Heavens and the Earth: The History of Jesuit Observatories. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic 2013.

- Vagiswari, A; Kameswara Rao, N; Birdie, C. & Priya Thakur: Michael Topping and the origin of the Madras Observatory. In: IIA Newsletter 14 (2009), 1, p. 16.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:47:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Smith, Blake: The Madras Observatory: from Jesuit cooperation to British rule

- Madras Observatory (Wikipedia)

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-08-13 10:15:12

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

223

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-04 09:32:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Jesuit astronomers arrived at Jaipur in 1734, and established the longitude of several of Jai Singh II’s cities. The Jesuits studyed Sanskrit, in order to translate the greatest works of South Asian astronomy. Sawai Jai Singh II (1688--1743), Maharaja of Amber and Jaipur, was considerably interested in mathematics, architecture and astronomy; very famous are his five observatories in Jaipur, Dehli, Mathura (Agra province), Varanasi (Benares province), Ujjain (Malwa province) -- large sundials and calendar buildings in order to determine time and date, or to measure the altitude and azimuth of celestial objects. But Jai Singh II’s observatrories lacked telescopes, which had been invented in Europe a century before.

But the influence of the Jesuits in India was not very long. After Jai Singh II died, the time of the Jesuits came already to an end. Then the British East India Company dominated. For the East India Company in the 1780s two things were important: navigation (time keeping, also for getting the longitude) and land surveying. Later in 1860, also geomagnetism was included besides astronomy.

Fig. 1. Old Madras Observatory, Egmore in Madras (1786), woodcut (Taylor 1838), (Wikipedia)

Madras Observatory (1786) was one of the first modern observatories in Asia. William Petrie (1784--1816) started to establish Madras Observatory in 1786 as a private observatory, made of iron and timber. Petrie donated his instruments to the Madras Government before retiring to England.

Fig. 2. Large Theodolite (engraving by Hawksworth), made by Jesse Ramsden, similar to the one made by William Cary which was used by Lambton during his surveying (Adams 1803, Wikipedia)

Since 1792, the Madras Observatory was moved to Nungambakkam in Madras and managed by the British East India Company in Madras (renamed as Chennai) -- in order to promote "the knowledge of astronomy, geography and navigation in India", the building was designed by Michael Topping (1747--1796), Chief Marine Surveyor of Fort St. George in Madras, founder of the oldest modern technical school outside Europe, College of Engineering since 1861. In 1788, he started surveying with a sextant.

Fig. 3. Lambton & Everest triangulations in central India since 1800 (Wikipedia)

His large triangulation project across India was taken over later by Lieutenant-Colonel William Lambton, FRS (~1753--1823). The Great Trigonometrical Survey (GTS) of India started 1800.

Fig. 4. Madras Observatory in Chennai, designed by Michael Topping (1792), 1880 (Government of India, 1926)

For over a century the Madras Observatory was the only astronomical observatory in India.

In contrast to the Greenwich Observatory, which came into existence without any instruments, Madras had valuable instruments (20-inch transit and a 12-inch azimuth transit circle instrument, made by Troughton of London, observations since 1793) (Kochhar 2002). In contrast to Jaipur, large telescopes were used in Madras -- very rare in the Indian subcontinent.

Fig. 5. John Goldingham (1767--1849) swinging a Kater’s pendulum, hung in front of a Haswell clock in Madras Observatory in 1821. The second assistant, Thiruvenkatachary, is reading the clock, while the first assistant, Srinivasachary, sitting near the 18-ft granite pier, is noting down the reading (Philosophical Transactions, 1822)

John Goldingham (1767--1849), 1796 to 1810 and 1812 to 1830, John Warren (1769--1830), Thomas Glanville Taylor (1804--1848), 1830 to 1848, and William Stephen Jacob (1813--1862), 1848 to 1859, were the successive Government Astronomers who dominated the activities at Madras.

Thomas Glanville Taylor published first "Results of Astronomical Observations Made at the Honorable the East India Companys Observatory at Madras, Vol. 1 for the Year 1831" (Madras 1832), then the "A General Catalogue of the Principal Fixed Stars from observations made at the Honorable, the East India Company’s Observatory at Madras in the Years 1830--1843, Vol. V" (Madras 1844).

In addition three solar eclipses (cf. Pang 2002, p. 16) were visible in India in 1868, 1871 and 1872, and in addition in 1874 the Transit of Venus. In 1868 the spectrum of prominences was observed; which led to the discovery of a bright yellow line (D3) near the sodium double lines as originating from the new element Helium.

Major James Francis Tennant (1829--1915) observed the total solar eclipse of 1868. He wanted to decide whether the prominances "are gaseous or consist of solid particles, whether they shine in their own light or in that of the Sun." Together with John Frederick William Herschel (1792--1871), Tennant was able to observe the solar eclipse (1868) from a station near Guntur. His attempt to photograph the corona was unsuccessful. However, he succeeded in observing a continuous spectrum of corona and emission lines in the spectrum of a prominance. Polariscope observations by other members of his group showed that the corona is not self-luminous, but reflects the light from the Sun’s surface. Tennant observed the solar eclipse (1871) in Doddabetta in the Nilgiri Mountains. Under his direction, spectroscopic observations were made, and photographs of the corona were obtained.

Tennant participated also in the Transit of Venus (1874) in Roorkee. He wanted to receive instruments from the Indian government, which could then be handed over to a solar observatory. Among other things, photographs of the important event were made.

Fig. 6. Madras Observatory (1880) (© IIA Archives, donated by Ms Cherry Armstrong, the great, great-grand daughter of Norman Pogson)

Madras Observatory is famous for the discovery of 58 asteroids and 21 variable stars. Norman Robert Pogson (1829--1891), director from 1860 to 1878, discovered 8 asteroids from 1856 to 1885, and 134 stars, 106 variable stars, 21 possible variable stars and 7 possible supernovae. His most famous contribution was the introduction of the logarithmic stellar magnitude system (1856): a first magnitude star is about 2.512 times as bright as a second magnitude star -- this fifth root of 100 is known as Pogson’s Ratio.

Pogson co-operated with the Indian astronomer Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary (1828--1880) since 1864. He determined the positions of stars for the Madras Star Catalogues. He also carried out observations of the total solar eclipses of 18 August 1868 (from Vunparthy, a village north of Kurnool) with Pogson, who made spectroscopic studies, and 12 December 1871 (from Avanashi, a town in Tamil Nadu province). In addition, he wrote a treatise on the Transit of Venus, observed on 9 December 1874. He noticed that a star, recorded at magnitude 8.5 by astronomer T. Moottooswamy Pillai with a with a meridian circle in February 1864, had become invisible by January 1866, but was picked up again by Chary on 16 January 1867. The discovery of the light variation of R Reticuli (Mira type variable star) by Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary in 1867 is perhaps the first astronomical discovery made by an Indian in modern times. Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1872 -- the first Indian to be elected to the RAS.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-06 01:10:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Instruments

- 20-inch Transit instrument, made by Troughton of London

- 12-inch Azimuth transit circle, made by Troughton of London

- 8-inch Equatorial, made by Cooke of London

- Transit circle, made by William Simms of London (1858)

- Vertical force magnetometer and declination magnetometer, about 1860

Major James Francis Tennant (1829--1915) was in charge of Madras Observatory, and magnetic observations were started using vertical force and declination magnetometers from 1859 to 1861.

In 1877 Joseph Norman Lockyer (1836--1920) suggested that the photoheliograph (cf. King’s Observatory, Kew), already in India, should be used for daily photography of the Sun; solar photography started at Dehra Dun in 1878. With a bigger photoheliograph in 1880 the work continued until 1925, when already Kodaikanal has overtaken these observations.

Fig. 7. Michael Topping (1747--1796) (Wikipedia)

Fig. 8. John Goldingham (1767--1849) (Wikipedia)

Directors -- Government Astronomers

- William Petrie (1784--1816), 1786 to 1789

- Michael Topping (1747--1796), 1789 to 1796

- John Goldingham (1767--1849), 1796 to 1810 and 1812 to 1830

- John Warren (1769--1830), 1810 to 1812

- Thomas Glanville Taylor (1804--1848), 1830 to 1848

- William Stephen Jacob (1813--1862), 1848 to 1859

- Norman Robert Pogson (1829--1891), 1860 to 1878

Fig. 9. Norman Robert Pogson (1829--1891) (Wikipedia)

Fig. 10. Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary (1828--1880) (Wikipedia)

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:45:10

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

There are only ruins of the Madras Observatory of the 18th century, stone slabs and broken pillars -- not comparable to the famous Jaipur Observatory site of Jai Singh II.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:45:37

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

--

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:46:01

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no longer existing

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:46:25

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Madras Observatory later evolved into the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IAU Code 220), Kavalur.

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:46:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The successor of Madras Observatory is the famous Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IAU Code 220), Kavalur.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:47:22

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Adams, George: Geometrical and graphical essays, containing, a general description of the mathematical instruments used in geometry, civil and military surveying, levelling and perspective; with many new practical problems. London: W. Glendinning, sold by William & S. Jones 1803.

- Ansari, S.M. Razaullah: On Indian observatories in the 19th century. In: Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 36 (1975), p. 523-530.

- Edney, Matthew H.: Mapping an Empire: The Geographical Construction of British India, 1765-1843, Volume 10. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1997, p. 172-173.

- Government of India: Report on the Administration of the Meteorological Department of the Government of India in 1925-26, and a Note on the Long-Established Observatories of Madras and Bombay. Simla: Government of India Press 1926, p. 1-4.

- J. L. E. D.: Obituary: Pogson, N. R. In: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 52 (1892), p. 235.

- Jacob, W.S.: Notes on the Total Eclipse of the Sun of July 18, 1860 as observed in Spain. In: Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal 13 (1861), (1), p. 1-6.

- Jacob, W.S.: Meteorological Observations Made at the Honorable East India Company’s Observatory at Madras in the Years 1851-1855. Madras 1874.

- Jacob, W.S.: Magnetical observations made at the Honorable East India Company’s Observatory at Madras in the years 1851-1855. Madras Observatory 1884.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: Madras Observatory: the beginning. In: Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India 13 (1985a), p. 162-168.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: Madras Observatory -- buildings and instruments. In: Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India 13 (1985b), p. 287-302.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: The growth of modern astronomy in India, 1651--1960. In: Vistas in Astronomy 34 (1991), p. 69--105.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K. & J. Narlikar: Astronomy in India. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy 1995.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K.: Madras and Kodaikanal Observatories: A Brief History. In: RESONANCE (August 2002), p. 16-28.

- Kochhar, Rajesh K. & Wayne Orchiston: Chapter 24: The Development of Modern Astronomy and Emergence of Astrophysics in India. In: Nakamura, T. & Wayne Orchiston (ed.): The Emergence of Astrophysics in Asia: Opening a New Window on the Universe. Cham: Springer 2017.

(doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-62082-4_24).

- Lockyer, Joseph Norman: Contributions in Solar Physics. London: Macmillan 1874.

- McConnell, Anita: Taylor, Thomas Glanville (1804--1848). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press (doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27089).

- McConnell, Anita: Jacob, William Stephen. In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press (doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14576).

- Orchiston, W.; Lee, E-H. & Y.-S. Ahn: British Observations of the 18 August 1868 Total Solar Eclipse from Guntoor, India. In: Nakamura, T. & Wayne Orchiston (ed.): The Emergence of Astrophysics in Asia: Opening a New Window on the Universe. Cham: Springer 2017.

- Pang, Alex: Empire and the Sun: Victorian solar eclipse expeditions. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2002.

- Pogson, Norman Robert: Madras Meridian Circle Observations in 1862-64. Madras: Government of Madras 1887.

- Reddy, V.; Snedegar, K. & R.K. Balasubramanian: Scaling the magnitude: the fall and rise of N. R. Pogson. In: Journal of the British Astronomical Association 117 (2007), no. 5, p. 237-245.

- Shylaja, B.S.: Chintamani Ragoonatha Charry and Contemporary Indian Astronomy. Bangalore: Bangalore Association for Science Education and Navakarnataka Publications Private Limited 2012.

- Smith, Blake: How The Madras Observatory Heralded the Rise of Modern Astronomy in India. In: Aeon (https://www.thebetterindia.com/118431/madras-observatory-modern-astronomy-jantar-mantar-india/).

- Taylor, Thomas Glanville: Result of Astronomical Observations made at the Honorable, the East India Company’s Observatory at Madras, Volume IV. 1836--1837. Madras 1838.

- Tennant, James Francis: Report on the Total Eclipse of the Sun, August 17-18, 1868. In: Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society 37 (1869), p. 1-55.

- Tennant, James Francis: Report of observations of the total eclipse of the Sun on December 11-12, 1871, made by order of the Government of India, at Dodabetta, near Ootacamund. In: Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society 42 (1875c), p. 1-33.

- Topping, Michael: Description of an Astronomical Observatory erected at Madras in 1792 by Order of the East India Company, Madras, 24th December 1792. MS, Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives. Cambridge 1792.

- Topping, Michael: VI. Part of a letter from Mr. Michael Topping, to Mr. Tiberius Cavallo, F.R.S. In: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 82 (1792), p. 99-114.

- Udías, Agustin: Searching the Heavens and the Earth: The History of Jesuit Observatories. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic 2013.

- Vagiswari, A; Kameswara Rao, N; Birdie, C. & Priya Thakur: Michael Topping and the origin of the Madras Observatory. In: IIA Newsletter 14 (2009), 1, p. 16.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-02 17:47:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Smith, Blake: The Madras Observatory: from Jesuit cooperation to British rule

- Madras Observatory (Wikipedia)

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-04 09:32:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Jesuit astronomers arrived at Jaipur in 1734, and established the longitude of several of Jai Singh II’s cities. The Jesuits studyed Sanskrit, in order to translate the greatest works of South Asian astronomy. Sawai Jai Singh II (1688--1743), Maharaja of Amber and Jaipur, was considerably interested in mathematics, architecture and astronomy; very famous are his five observatories in Jaipur, Dehli, Mathura (Agra province), Varanasi (Benares province), Ujjain (Malwa province) -- large sundials and calendar buildings in order to determine time and date, or to measure the altitude and azimuth of celestial objects. But Jai Singh II’s observatrories lacked telescopes, which had been invented in Europe a century before.

But the influence of the Jesuits in India was not very long. After Jai Singh II died, the time of the Jesuits came already to an end. Then the British East India Company dominated. For the East India Company in the 1780s two things were important: navigation (time keeping, also for getting the longitude) and land surveying. Later in 1860, also geomagnetism was included besides astronomy.

Fig. 1. Old Madras Observatory, Egmore in Madras (1786), woodcut (Taylor 1838), (Wikipedia)

Madras Observatory (1786) was one of the first modern observatories in Asia. William Petrie (1784--1816) started to establish Madras Observatory in 1786 as a private observatory, made of iron and timber. Petrie donated his instruments to the Madras Government before retiring to England.

Fig. 2. Large Theodolite (engraving by Hawksworth), made by Jesse Ramsden, similar to the one made by William Cary which was used by Lambton during his surveying (Adams 1803, Wikipedia)

Since 1792, the Madras Observatory was moved to Nungambakkam in Madras and managed by the British East India Company in Madras (renamed as Chennai) -- in order to promote "the knowledge of astronomy, geography and navigation in India", the building was designed by Michael Topping (1747--1796), Chief Marine Surveyor of Fort St. George in Madras, founder of the oldest modern technical school outside Europe, College of Engineering since 1861. In 1788, he started surveying with a sextant.

Fig. 3. Lambton & Everest triangulations in central India since 1800 (Wikipedia)

His large triangulation project across India was taken over later by Lieutenant-Colonel William Lambton, FRS (~1753--1823). The Great Trigonometrical Survey (GTS) of India started 1800.

Fig. 4. Madras Observatory in Chennai, designed by Michael Topping (1792), 1880 (Government of India, 1926)

For over a century the Madras Observatory was the only astronomical observatory in India.

In contrast to the Greenwich Observatory, which came into existence without any instruments, Madras had valuable instruments (20-inch transit and a 12-inch azimuth transit circle instrument, made by Troughton of London, observations since 1793) (Kochhar 2002). In contrast to Jaipur, large telescopes were used in Madras -- very rare in the Indian subcontinent.

Fig. 5. John Goldingham (1767--1849) swinging a Kater’s pendulum, hung in front of a Haswell clock in Madras Observatory in 1821. The second assistant, Thiruvenkatachary, is reading the clock, while the first assistant, Srinivasachary, sitting near the 18-ft granite pier, is noting down the reading (Philosophical Transactions, 1822)

John Goldingham (1767--1849), 1796 to 1810 and 1812 to 1830, John Warren (1769--1830), Thomas Glanville Taylor (1804--1848), 1830 to 1848, and William Stephen Jacob (1813--1862), 1848 to 1859, were the successive Government Astronomers who dominated the activities at Madras.

Thomas Glanville Taylor published first "Results of Astronomical Observations Made at the Honorable the East India Companys Observatory at Madras, Vol. 1 for the Year 1831" (Madras 1832), then the "A General Catalogue of the Principal Fixed Stars from observations made at the Honorable, the East India Company’s Observatory at Madras in the Years 1830--1843, Vol. V" (Madras 1844).

In addition three solar eclipses (cf. Pang 2002, p. 16) were visible in India in 1868, 1871 and 1872, and in addition in 1874 the Transit of Venus. In 1868 the spectrum of prominences was observed; which led to the discovery of a bright yellow line (D3) near the sodium double lines as originating from the new element Helium.

Major James Francis Tennant (1829--1915) observed the total solar eclipse of 1868. He wanted to decide whether the prominances "are gaseous or consist of solid particles, whether they shine in their own light or in that of the Sun." Together with John Frederick William Herschel (1792--1871), Tennant was able to observe the solar eclipse (1868) from a station near Guntur. His attempt to photograph the corona was unsuccessful. However, he succeeded in observing a continuous spectrum of corona and emission lines in the spectrum of a prominance. Polariscope observations by other members of his group showed that the corona is not self-luminous, but reflects the light from the Sun’s surface. Tennant observed the solar eclipse (1871) in Doddabetta in the Nilgiri Mountains. Under his direction, spectroscopic observations were made, and photographs of the corona were obtained.

Tennant participated also in the Transit of Venus (1874) in Roorkee. He wanted to receive instruments from the Indian government, which could then be handed over to a solar observatory. Among other things, photographs of the important event were made.

Fig. 6. Madras Observatory (1880) (© IIA Archives, donated by Ms Cherry Armstrong, the great, great-grand daughter of Norman Pogson)

Madras Observatory is famous for the discovery of 58 asteroids and 21 variable stars. Norman Robert Pogson (1829--1891), director from 1860 to 1878, discovered 8 asteroids from 1856 to 1885, and 134 stars, 106 variable stars, 21 possible variable stars and 7 possible supernovae. His most famous contribution was the introduction of the logarithmic stellar magnitude system (1856): a first magnitude star is about 2.512 times as bright as a second magnitude star -- this fifth root of 100 is known as Pogson’s Ratio.

Pogson co-operated with the Indian astronomer Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary (1828--1880) since 1864. He determined the positions of stars for the Madras Star Catalogues. He also carried out observations of the total solar eclipses of 18 August 1868 (from Vunparthy, a village north of Kurnool) with Pogson, who made spectroscopic studies, and 12 December 1871 (from Avanashi, a town in Tamil Nadu province). In addition, he wrote a treatise on the Transit of Venus, observed on 9 December 1874. He noticed that a star, recorded at magnitude 8.5 by astronomer T. Moottooswamy Pillai with a with a meridian circle in February 1864, had become invisible by January 1866, but was picked up again by Chary on 16 January 1867. The discovery of the light variation of R Reticuli (Mira type variable star) by Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary in 1867 is perhaps the first astronomical discovery made by an Indian in modern times. Chinthamani Ragoonatha Chary was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1872 -- the first Indian to be elected to the RAS.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 124

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-06 01:10:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Instruments

- 20-inch Transit instrument, made by Troughton of London

- 12-inch Azimuth transit circle, made by Troughton of London

- 8-inch Equatorial, made by Cooke of London

- Transit circle, made by William Simms of London (1858)

- Vertical force magnetometer and declination magnetometer, about 1860

Major James Francis Tennant (1829--1915) was in charge of Madras Observatory, and magnetic observations were started using vertical force and declination magnetometers from 1859 to 1861.

In 1877 Joseph Norman Lockyer (1836--1920) suggested that the photoheliograph (cf. King’s Observatory, Kew), already in India, should be used for daily photography of the Sun; solar photography started at Dehra Dun in 1878. With a bigger photoheliograph in 1880 the work continued until 1925, when already Kodaikanal has overtaken these observations.

Fig. 7. Michael Topping (1747--1796) (Wikipedia)

Fig. 8. John Goldingham (1767--1849) (Wikipedia)

Directors -- Government Astronomers

- William Petrie (1784--1816), 1786 to 1789

- Michael Topping (1747--1796), 1789 to 1796

- John Goldingham (1767--1849), 1796 to 1810 and 1812 to 1830

- John Warren (1769--1830), 1810 to 1812

- Thomas Glanville Taylor (1804--1848), 1830 to 1848