Category of Astronomical Heritage: dark skies

Western Alpine and Grana Valley Sky Sanctuary, Italy

Format: Full Description (IAU Extended Case Study format)

Identification of the property

Country/State Party - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-05-17 13:21:05

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Italy / Western Alps

State/Province/Region - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-07 19:06:52

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Italy/Cuneo/Piedmont

Name - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-05-17 13:21:58

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Fauniera Pass, Municipality of Castelmagno, Grana Valley, (Cottian Alps)

Geographical co-ordinates and/or UTM - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-05-17 13:22:22

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Geographical area that includes Colle Fauniera, the sanctuary of Castelmagno,

and the municipal area of Castelmagno.

Colle Fauniera: 2481 m above sea level 44 ° 23′08.56 ″ N 7 ° 07′18.79 ″ E

Castelmagno Sanctuary: 1760 m above sea level 44 ° 17 ’46.12 "N - 7 ° 17’ 13.24" E

Municipality of Castelmagno: from 2,600 to 700 m above sea level.

long axis (about WE) 44 ° 23′08.56 ″ N 7 ° 07′18.79 ″ E at 44 ° 24’49.5 "N 7 ° 15’00.6" E

short axis (about NS) 44 ° 26’02.3 "N 7 ° 12’58.9" E at 44 ° 22’49.9 "N 7 ° 13’03.2" E

Buffer Zone

Geographical area that includes the Grana Valley (Cottian Alps)

Grana Valley: from 2600 to 500 m above sea level.

Long axis (approx. W-E): 44°23′08.56” N,7°07′18.79”E to 44°25′59.3” N, 7°29′00.5”E

Short axis (approx. N-S): 44°26′02.3” N, 7°12′58.9” E to 44°22′49.9”N, 7°13′03.2”E

Maps and plans,

showing boundaries of property and buffer zone - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-05-27 13:01:16

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

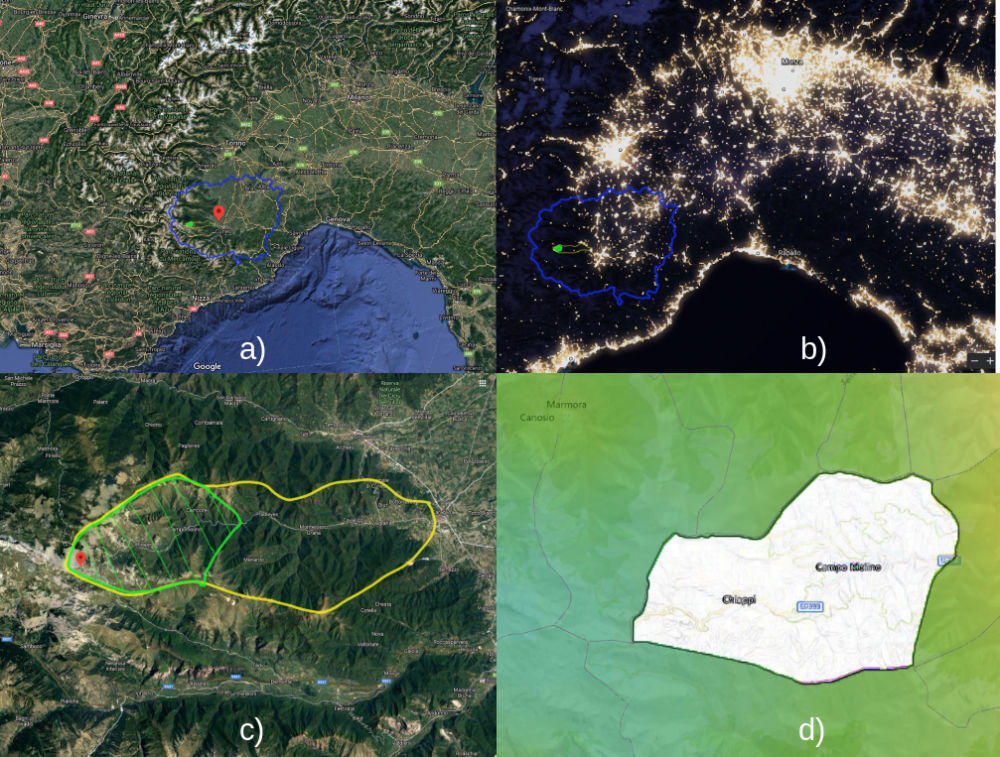

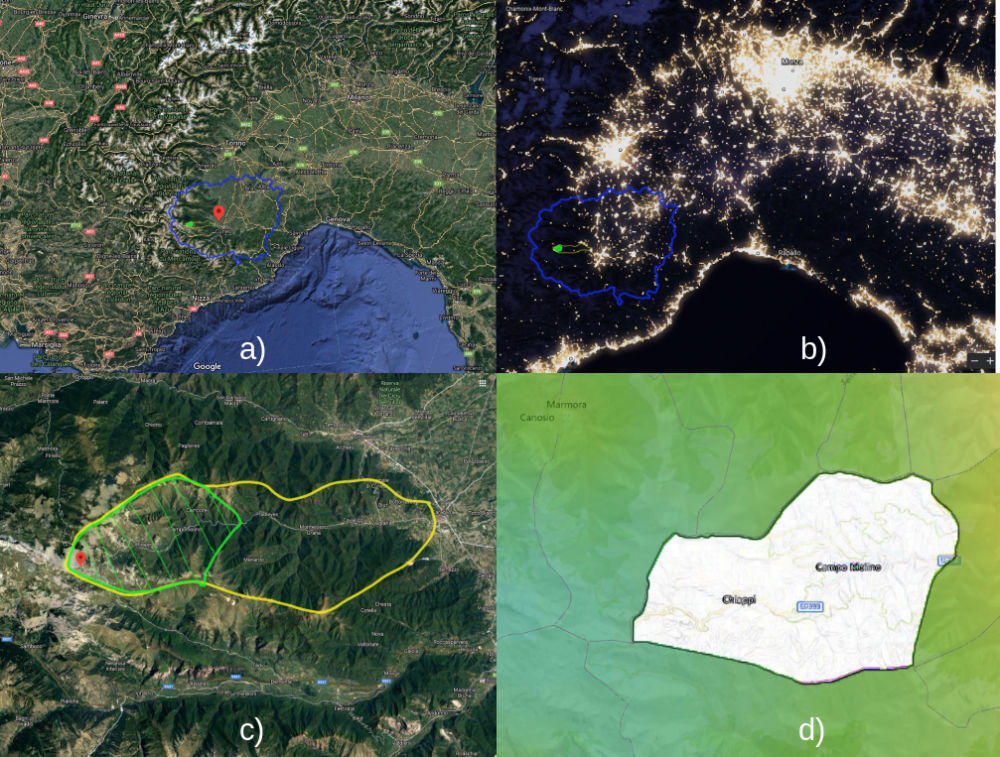

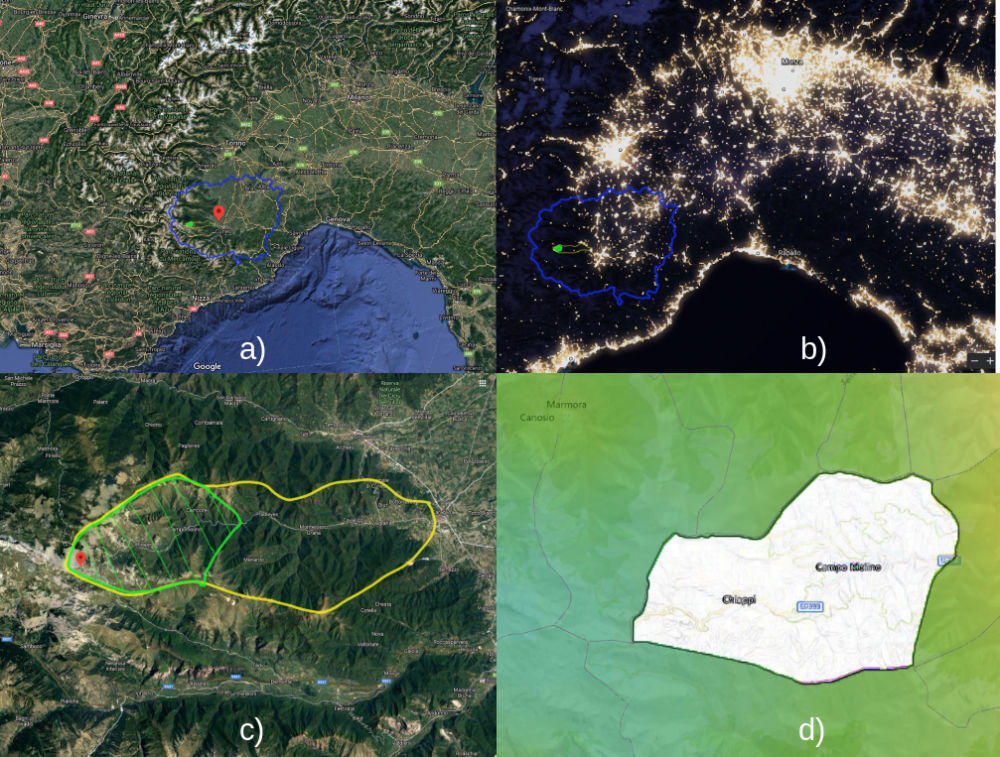

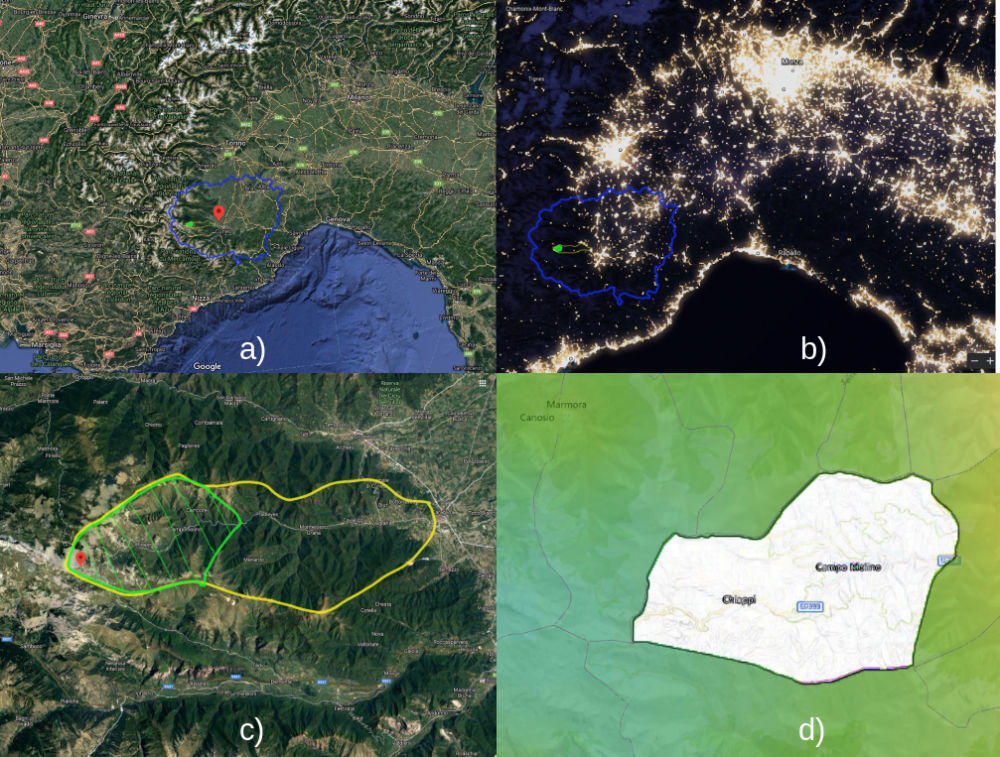

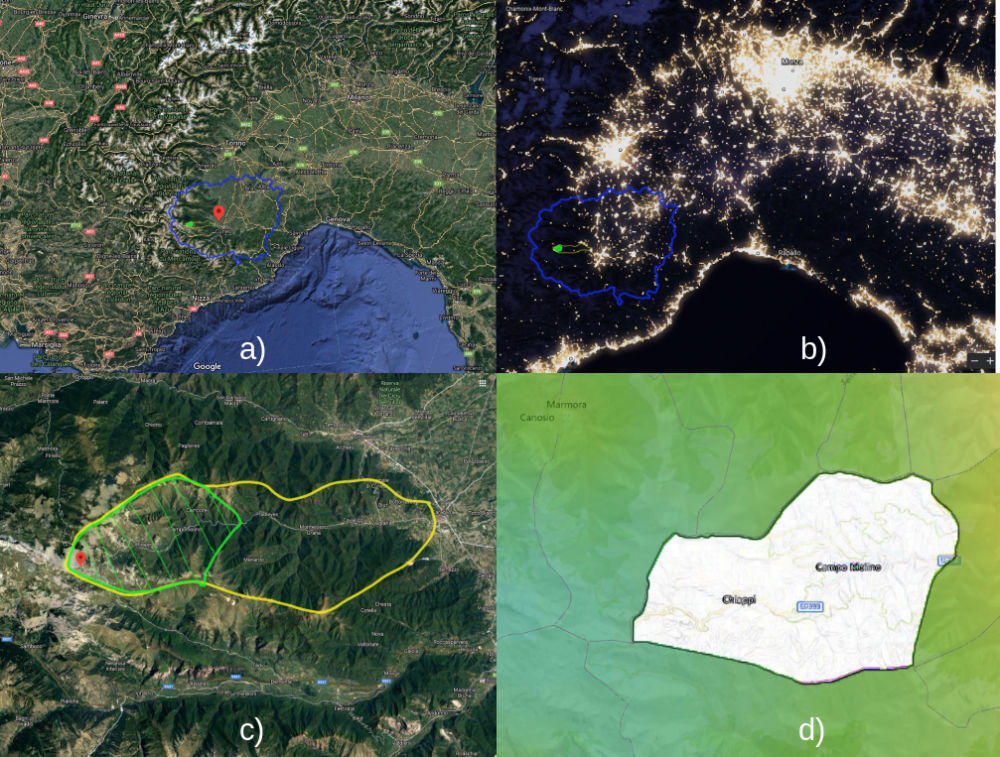

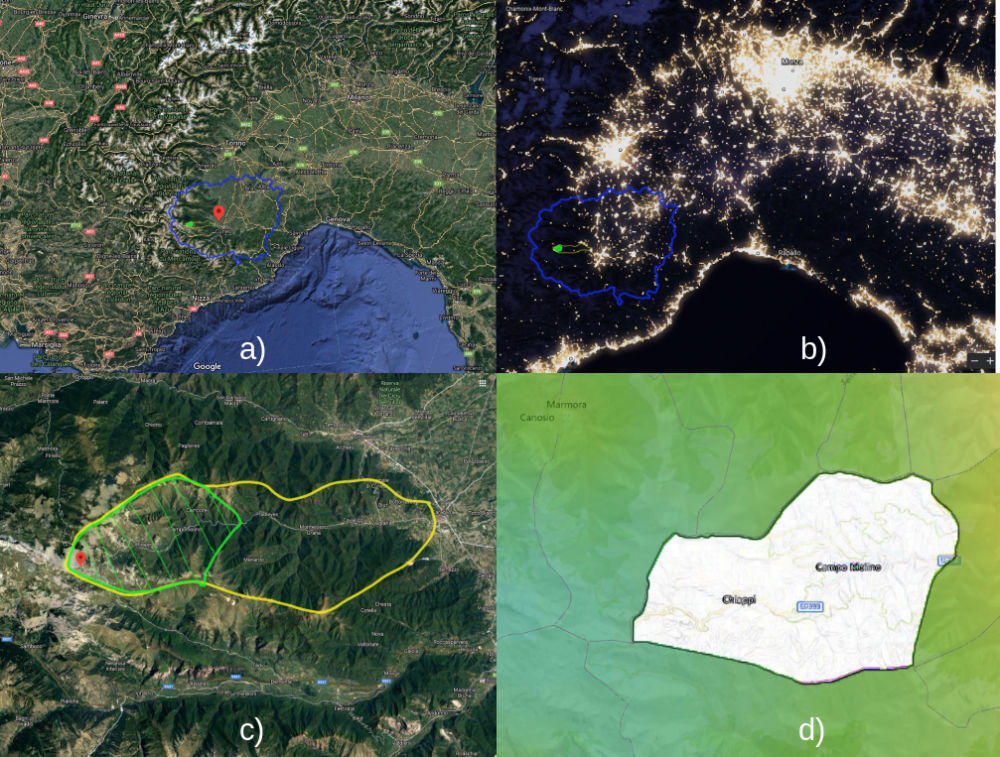

Fig. 1. a) Google aerial view of Piedmont area. b) Night view of piedmont with buffer and core zone. c) Grana Valley with boundaries of the Core and Buffer Zone. d) Core Zone: Municipal area of Castelmagno. Blu line identifies Cuneo district, the yellow line the Buffer Zone, the green one the Core Zone.

Area of property and buffer zone - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-07 19:07:13

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Core Zone: 43,31 km²

Municipality of Castelmagno, Colle Fauniera

Buffer Zone: 97 km²

Municipality of: Caraglio, Montemale, Valgrana, Monterosso Grana and Pradleves.

Description

Description of the property - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 9

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-25 11:58:44

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

The Valle Grana is a valley in the province of Cuneo, Piedmont, northern Italy.

It takes its name from the Grana stream, a tributary of the Maira which flows through the valley.

The territory of the municipality of Castelmagno and the Fauniera pass, set in the upper Grana valley, are part of a unique alpine landscape characterized by a starry sky, almost uncontaminated.

With an area of 43 km², this landscape represents a unique heritage from a historical, naturalistic and astronomical point of view.

The central area is divided into two distinct sites lying in the municipality of Castelmagno:

- Fauniera Pass

- Sanctuary of Castelmagno

These areas are located at the apex of the buffer zone which then extends with a territory of about 130 km² up to the bottom of the valley with the municipality of Caraglio.

The territory of the Grana Valley extends from the Po Valley to the Alpine peaks that reach 2600 m. It is located in the southwestern Alps, a bio-geographical region close to the Mediterranean area and renowned for its high level of biodiversity and for hosting many endemic species.

Fig. 2. Landscape of the Grana Valley

Geological and geo-morphological framework

The valley with a development of about 25 km and east-west direction, sits entirely on rocks belonging to the Pennidic region. Much of the valley development, from Caraglio to the Sanctuary of San Magno is divided into the Piedmontese area of calcescisti with Green Stones (with the only exception of Pradleves). A little west of the Sanctuary there is the tectonic contact with the Brianzonese area, in particular the base represented mainly by the Permian acid volcanites or by its metamorphic derivatives.

In the higher part of the valley, near Colle Fauniera, the sedimentary covers of the Brianzonese also emerge, little or not at all metamorphosed as in most of the southern Brianzonese, represented by limestone, dolomitic limestone and Triassic carneole.

As mentioned above, to the south and south-west of Pradleves, thanks to the presence of a small tectonic window, the Inland Massif of Dora Maira emerges in a very limited range, represented mainly by gneisses and micascists.

From a geomorphological point of view, the valley can be divided into 3 different areas. The valley floor, from Caraglio to Monterosso Grana, where the morphology linked to glacial erosion has been partly hidden by the fluvial sediments that have filled the valley floor, creating large river terraces and drowning any moraines present. From Pradleves to Campomolino the valley has a typically fluvial current morphology, where the glacial forms have been eroded in favor of a particularly carved valley and deep side valleys. From Campomolino upwards, especially starting from the Sanctuary of San Magno, the valley has wide open spaces shaped by the feeding area of the Pleistocene glaciers and by circus glaciers.

Geology of high Grana Valley

As can be seen from the study of the geological map of Italy, Foglio Argentera - Dronero, near the Sanctuary of San Magno there is the tectonic contact that separates the Calcescisti Zone (to the north-east) from the Brianzonese Zone (to the south-west). This continues towards the SE on the left side of the valley and then develops into the Valloriate valley (Valle Stura) and towards the SW in the Sibolet Valley, emerging along the slopes of Mount Tibert and continuing towards Canosio and Valle Maira.

The Brianzonese area here in the upper Grana valley is represented, as anticipated in the framework, both by the base of Hercynian origin and by the Mesozoic sedimentary coverings attributable to the Tethys ocean. Using the valley road as a reference, from the Sanctuary to Ponte Fonirola, under the Rocca Parvo, where there are no glacial or detrital deposits, some schists with quartz and sericite and quartzites emerge, both metamorphic rocks of the Permian and Carboniferous, therefore attributable to the so-called “Ercinico’’ base, which therefore constituted the Pangea continent and which already show an initial phase of rift and a marine ingress or fluvial and / or shallow sea deposits, attributable to the first phases of opening of the Tethys Ocean.

The peculiarity of this succession, common to the whole Brianzonese area, is the large stratigraphic gap of the Lower and Middle Jurassic, evidence of a general phase of emergence and subaerial erosion.

The Brianzonese sedimentary succession is considered to be the testimony of a basin within a passive margin, that is, the margin of a continent subject to rift. The sedimentary succession is considered as a flap of the European paleo-margin. The current tectonic limits that divide the different zones derive from the Mesozoic extensional limits and have allowed the crust to thin out during the extensional phase, and then reactivate as sliding planes during the Alpine orogeny.

The “laouziere” of San Pietro Monterosso

The slate quarries of San Pietro, also called the "laouziere" from the name "losa", the type of stone extracted; represented a fundamental nucleus in the working and social life of the Grana Valley between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries. For centuries the “losa” were the only material used for the roofing of the buildings in the Grana Valley and, after a local diffusion, from the middle of the 18th century these kind of stones extracted in San Pietro, considered the most valuable in the Cuneo area, began to be exported throughout the Province of Cuneo.

A few kilometers from the village of San Pietro, in ten real caves, dug into the rock, belonging to as many historical families from the nearby villages of Frize, Fougirouss and Combetta, the quarrymen (laouzatie) worked mostly in winter, for climate issues and time availability.The mining activity continued also in the 1900s, during the wars - when a system of cableways was installed to transport the material downstream and other systems such as rails and trolleys inside the quarries - and in the second half of the 1900s the activity was more than ever thriving and productive. The end of the activity coincides with December 31, 1983, when very restrictive regulations made the extraction uneconomic and the workers abandoned the quarries.The sudden and total abandonment of the site gives us an image of intact extractive industrial archeology.

Fig. 3. The “laouziere of San Pietro” (credit Federico Pellegrino)

The “laouziere of San Pietro”, today, carve the ridge of the mountain giving us a suggestive and unique place from an environmental point of view that is also told with the traces of the past mining activity, such as the traces and remains of the cable car that was used to transport the material to Valley.

Flora and Fauna

As usual in the Alps, vegetation is strongly correlated to altitude with four altitudinal zones[6][10] described below.

The plain and foothills area (600-1000 m above sea level) is the lower part of the territory. While the valley floor is currently occupied by crops, orchards and meadows, the slopes are largely covered by chestnut woods (Castanea sativa) both coppices in the rewilding phase and ancient traditional chestnut grove with centuries-old trees. In this landscape there are particularly warm areas on the southern slopes with arid oak woods (Quercus pubescens) and shrubs[27].

Mountain area (1000-1700 m). This area is mostly covered with a dense mountain beech forest (Fagus sylvativa) usually on steep slopes which greatly affect the vegetation. On the northern slopes there is a good availability of water and moisture in the soil while on the southern slopes, even if the beech is the most common tree, the undergrowth and shrubs are mostly drought-resistant plants. Pastures are present in the most favorable situation for grazing).

Subalpine area (1700-2300 m). Unlike other alpine areas of the Grana Valley, the subalpine area is not dominated by conifers due to the suboceanic climate and anthropogenic management. On the southern slopes, the area suitable for grazing consists mainly of alpine pastures dominated by Matgrass (Nardus stricta) and Red Festuca (Festuca paniculata) and other herbs. On the snow-covered and steep slopes, especially those facing north, there are large expanses of green alder (Alnus viridis) scrub rich in tall grasses. In intermediate conditions where some grazing is still possible, the vegetation is also composed of Rusty Alpenroses and blueberries (Rhododendron ferrugineum, Vaccinium sp.) Or junipers (Juniperus communis)[26].

Alpine area (2300-2600 m). This area is above the treeline and is dominated by an alpine tundra landscape. Many areas are still used as summer pastures. The most common vegetation is a prairie with dominant Matgrass (Nardus stricta) and Poa Alpina but rich in alpine species such as Gentians (Gentiana sp.) And Wolf’s Bane (Arnica montana). On calcareous soil, the prairies of evergreen wax sedge (Carex sempervirens) are also important. On the peaks and ridges the vegetation is scarce and composed of high resistance alpine plants, while on snowy depressions and valleys there are dwarf creeping willows (Salix herbacea, Salix reticulata ) of the same species that lives in the Arctic tundra.

In addition to the above, it should be noted that both the mountain and the foothills are covered by a large extension of invasive secondary forest of ash (Fraxinus excelsior) and field maple (Acer campestre) and along the Grana river and its major tributary streams it is common. have a narrow band of common alder (Alnus glutinosa) and willow (Salix eleagnos) shrubs on the rocky bed of the stream.

Most of the vegetations described above are quite common throughout the surrounding area of the southwestern Alps [22][10]. On the other hand, some habitats and species are present in Valle Grana which are quite rare outside the valley and are therefore particularly important and result in the designation of Site of Community Importance by the European Community [1][2][39].

In the central area of the valley, the Grana river digs a deep gorge on limestone rocks. This peculiar landscape of rocky walls and steep slopes is occupied by a rare form of shrubby boxwood (Buxus sempervirens) which interpenetrates with the surrounding forest. This habitat is a rare example of evergreen broadleaf vegetation rich in Mediterranean species in a temperate region. Near Pradleves there are very well preserved and highly representative examples of petrifying springs. These habitats are very rare and small in extent. There lives a community of mosses (Cratoneurion commutatum) specialized in calcareous water which causes the active formation of tuff or travertine. Occasionally, even at low altitudes, dry open meadows with erect Bromine (Bromus erectus) are present. Those grasslands exist because of the particular local conditions and because in the past they were cultivated or grazed. They are rich in drought tolerant Mediterranean species including many rare orchid species (Ophrys fuciflora, Orchis tridentata, Orchis militaris, Anacampitis pyramidalis, Aceras antropophora) and the rare Beautiful Flax (Linum narbonense).

Fig. 4. Coriophora dell’Infernet

A great influence on vegetation has had previous human activities. The variety of vegetation in relation to the altitude is favorable to pastoralism with transhumance practiced since prehistoric times which paved the way for the stable colonization of the mountains. The local population initially relied almost completely on local natural resources, using wood from the forest for both energy and construction; clearing of the land to make room for harvesting and hay meadows even on very steep and uneven terrain. Grazing with small flocks of sheep and goats made it possible to profit from marginal land and poor grazing areas. The mountain population peaked in the nineteenth century before plummeting with industrialization and emigration. When the population was at its peak, local resources began to suffer and the local population often resorted to seasonal emigration. The wooded area was very small due to the production of firewood and coal for urban and industrial uses, almost all of the suitable land was already used as pasture or crops, and the local fauna was scarce due to excessive hunting.

After the Second World War with the rapid industrialization of the country, the population concentrated in large cities and towns on low lands and traditional land use ceased[16] . The cultivation of crops on mountainous terrain has disappeared with the sole exception of chestnut cultivation, giving space to the prairie and therefore to the woods or scrub-land. The pastures have seen the abandonment of marginal areas and a concentration of livestock on the more favourable and accessible ones, together with a much lower use of haymaking and sheep farming. As a result, over the past 70 years many areas have converted from open landscapes to secondary forests or shrubs as a result of a natural process of reforestation or sometimes of artificial conifer plantations. The existing forest has undergone a growth process due to abandonment or less exploitation. Forests currently contain much more wood and many coppices are evolving into natural forests.

The vegetation of the Grana Valley is currently in a fairly good state of conservation due to low anthropogenic activity in most of the territory. However, the local environment is still suffering the consequences of the high pressure on natural resources by the local population in the past. This happens in particular with regard to the forest: there is hardly any old-growth wood left and even single old trees are very rare with the exception of the cultivated chestnut. Currently the main threat to the vegetation is the invasion of exotic species. Recently the Bosso Comune (Buxus sempervirens) has been attacked by a recently introduced pest, the Bosso moth (Cydalima perspectabilis) which appears to be capable of almost completely destroying the Bosso population [28] . Another common threat to the drying out of open vegetation is the natural reforestation process in the absence of traditional human management. Even if caused by a natural process, it could result in a loss of valuable species and habitats [29]. Many pastures, especially in the subalpine area around Castelmagno, also suffer from the strong grazing pressure which translates into a lower biodiversity of the habitat of the prairies.

Although of limited extension, the Grana valley has a remarkable altitude range without however reaching 3000 m. of altitude, and therefore presents the different environments typical of the mountain, subalpine, lower and upper alpine planes [33]. In each of these we will find a characteristic fauna, known to the valley dwellers with dialectal names that may vary slightly in the different districts of the valley.

At higher altitudes you will see the golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) fly, this is quite rare because it requires fly, quite rare because it requires a large territory to be able to nest[40]. Occasionally it is possible to see the Bearded Vulture (Gypaetus barbatus), recently reintroduced with success in other valleys after a century from its disappearance in the Alps. This is the environment of the Marmot (Marmota marmota), which in some cases has become rather daring, and of the Chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra), which represent the picture of the most iconic high altitude animals.

Descending in altitude, animals related to woodland areas [11] become more common, such as the wild boar (Sus scropha), which has been expanding sharply for at least 30 years, and the roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), which is also expanding and ever closer to homes. The abundance of food has offered the wolf (Canis lupus) the possibility of spontaneously resettling in the valley after about a century of absence. The specimens present are being studied as part of the Life Wolf Alps EU project, which is still ongoing, but it seems that they are not very numerous on site due to the need for large spaces to feed.

In the beech, ash, birch or chestnut woods, birds such as Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs), Great Tit (Parus major) or Wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) are frequently encountered, even near the inhabited hamlets, while at night Tawny Owl (Strix aluco) and Little owl (Athene noctua) and the Long-eared Owl (Asio otus) play their songs that have inspired shady legends among the mountain people. The red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) is present here, albeit in fewer numbers than in the past.

This is the habitat of choice for the stag beetle (Lucanus cervus), a showy beetle 4 cm long and with extremely developed jaws, which it uses in fights between males.

The clearings and meadows, cultivated or not, also host a rich fauna of insects, reptiles and amphibians, each with a dedicated story in the oral traditions of the valley dwellers. From the Toad (Bufo bufo), of which the irritating activity of the subcutaneous glands used in folk medicine was known, to the Salamandra (Salamandra salamandra), an animal always surrounded by legends about the alleged danger of its (harmless) poison, to the Rana temporaria , common in the mountains and often used in cooking, especially until a few decades ago.

Among the reptiles we remember the Viper (Vipera aspis), rarer than what is normally thought because it is often confused with the more common Coronella austriaca, which often comes close to houses. The large and harmless Sand Snake (Hierophis viridiflavus) hunts Wall Lizards (Podarcis muralis) and small rodents, while the Orbettino (Anguis veronensis), despite being a saurian and not an ophid, however completely harmless, has still carved out a grim reputation alive in the tales of the elderly.

In the open areas you can see the rare Apollo (Parnassius apollo), a butterfly representative of high and medium altitudes, which can be heard approaching thanks to the particular rustle of the wings emitted during the flight.

The brown trout (Salmo trutta fario), a fish with a long gastronomic tradition, is often found in the streams of the valley floor, and in many cases also in the canals of the side valleys.

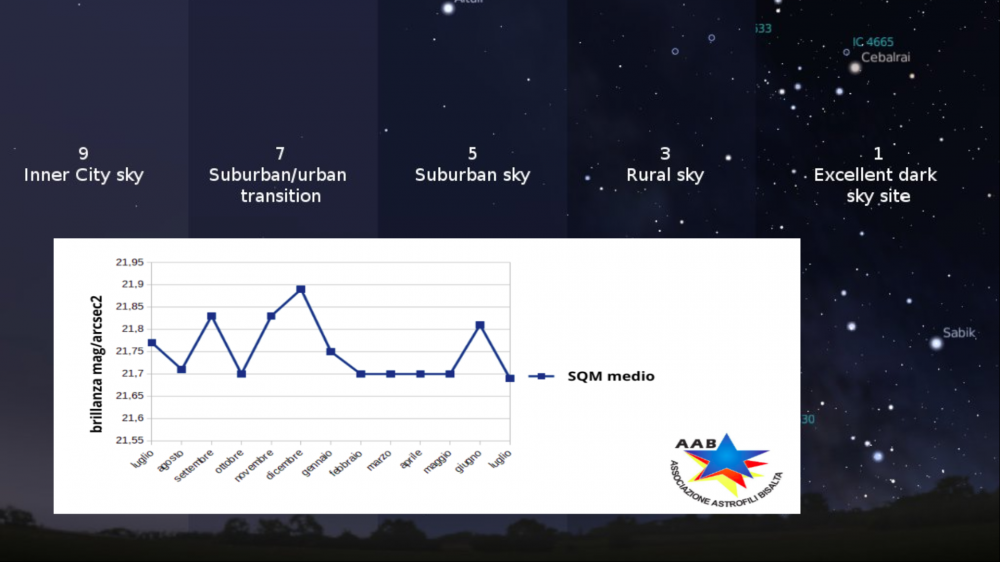

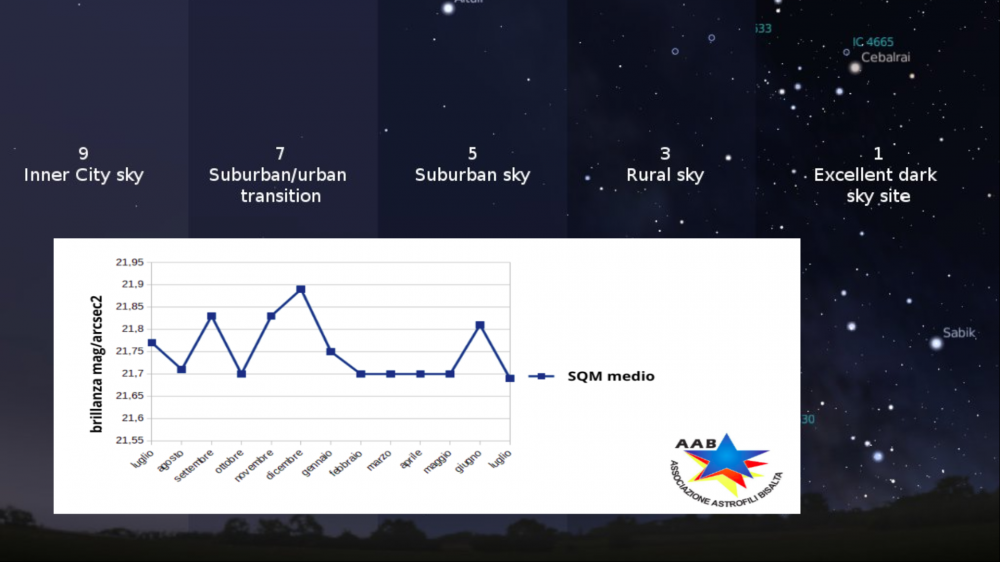

Both alpine habitats have a quality of sky worthy of the best astronomical sites in the world, the faunal hill with an almost completely natural daylight and night light, preserves practically intact the sky-landscape heritage of the place, the site of Castelmagno for as it is man-made, it has an average quality of darkness with Sky Quality Meter (SQM) of 21.65 / 21.70 mag / arcsec2.

However, it is beyond the scope of this case study to attempt a complete, integrated discussion of integrity and authenticity including both astronomical and non-astronomical aspects.

Instead, we would like to focus upon the possible connections and relations between astronomically determined environmental factors in a broad sense and potential cultural, archaeological and science-historical values.

From a cultural perspective, the authenticity of the night sky surely concerns how well its appearance today reflects its appearance to the cultures that had a connection with it in the past.

From a naturalistic perspective, the question is what is the value of the integrated sky-landscape system and how an uncontaminated sky can guarantee low anthropization and integrity.

However, a critical factor is the quality of the sky, as discussed in other sections.

Visibility of the entire firmament is an important factor that can testify to integrity or whether nature has been compromised. While a relatively intact night sky remained in most places until the 19th century, it is now evident that the night situation has significantly changed the appearance of many heritage sites, including world heritage sites, at night. Some of this may also come, ironically, from efforts to improve the look of the heritage itself by lighting it up at night.

The dark sky is today a sign of authenticity.

History and development - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-25 12:27:56

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

The Grana valley is part of the western Alps and is listed among the valleys of the Cottian Alps. Unlike its neighbors it does not reach the watershed that forms the border with France, because it is set between the Stura and Maira valleys.

Prehistory

The beginning of human settlement in the Grana valley cannot be established with certainty. To date, the oldest traces seem to consist of some engravings depicting human figures [8] found on two boulders found in the "Costa" locality just above the "Campofei" hamlet. According to scholars, these engravings date back to the Bronze Age, in an unspecified period between the end of the third millennium and the end of the second millennium BC. The presence of these engravings, common in form and representation to other similar examples found throughout the Alps and even beyond the French border (Vallée des Merveilles), lead us to us hypothesize that even in very remote times, the first inhabitants of the Alpine valleys were able to move from valley to valley to search the most favorable conditions for survival and transporting their wealth of knowledge to their new settlements.

Fig. 5. Rock engravings in Valle Grana, locality "La Costa", just above the village "Campo Fey" at an altitude of the sea 1624m.

Pre-Roman period, mountain Ligurians and Romanization of the Western Alps

In pre-Roman times, the mountain area that included the initial part of the Ligurian Apennines and the Western Alps was inhabited by Ligurian tribes [21]. In particular by the Liguri Montani (mountain Ligurians). These populations, tempered by the hard life in the mountains, were represented in almost all ancient sources as vigorous, resistant and agile populations. Tito Livio defines them: "velox et abentinus", adjectives that immediately make us understand their speed even in carrying out arms sorties against Roman troops or raids against the commercial caravans that passed through the communication routes that ran in the valley floor.

The relationship between the Ligurian populations settled in the Maritime Alps and the Romans must not have been simple and peaceful. For the Romans, the Alps were always an inhospitable, terrible place (le tremendae Alpes) and, if possible, to be avoided.

However, first with the expeditions of Julius Caesar [22][26] to Gaul and then with the definitive settlement of the region by Augustus, the legions of the empire had to deal with valleys, mountains, hills and passes. Unlike the Cozi, based further north, the Ligurian Montani of the Maritime Alps did not come to terms with Rome [17]. On the contrary, they triggered a war of liberation from Roman domination which was becoming more and more pressing. The leader of the Ligurian tribes stationed south of Cozi and straddling the Alps, Ideonno, was however defeated. Some districts of the French side, which had previously been under its control, were ceded to the Cozi while the remaining part which included the Alpine territory up to the valley floor and along the trajectory that connected Borgo San Dalmazzo, Cervasca, Caraglio and Piasco (the XL Galliarum) was organized in a new province known as the Alpes Maritimae. Of these centers, Caraglio, the ancient Forum Germanorum, had to have a certain importance.

It is, perhaps, to have more control over the unpredictable actions of the Ligurians that the Roman army decided to found fortified camps (castra). One of them had to be fixed at the top of the Grana valley. The toponym Castelmagno derives from Castrum Magnum.

However, it seems that the real site of the camp coincided with the current settlement of Colletto. Here, however, no particular archaeological finds have been found. While around the area now occupied by the Sanctuary of San Magno, coins, vases and fibulae from the Roman era dating back to the third century AD were found during some works. Digging under the altar of the old chapel in search of the relics of the patron saint, a small pillar was also found, part of a votive altar dedicated to Mars restorer.

Like other churches of Val Grana (for example Santa Maria della Valle), the Sanctuary of San Magno was therefore built on ancient pagan places of worship. With the Romanization process, the Grana Valley saw the settlement of some groups and families of Latin origin or perhaps already present in the area and of Ligurian descent who assumed Roman citizenship. This is the case, for example, of Leves. It is a family that settled in the area between Monterosso Grana and Pradleves. Among the most accredited hypotheses to explain the origin of the toponym of Pradleves there is precisely the one that it derives from Pratum Levesium (the meadows of Leves). Evidence of Roman settlements in the Grana valley is scarce in size but numerous. There are a lot of sites where fragments of terracotta and ceramics of various kinds were found. They testify to a certain liveliness of daily life. The epigraphs that tell the devotion of the people of the Valle Grana to the emperors deserve a separate mention, as in the case of the stele found near the bridge that crosses the Grana stream near the hamlet of Santa Maria di Valgrana and dedicated to the philosopher the emperor Marco Aurelio or the funerary epigraphs found both in Caraglio and in Valgrana.

Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages

There is no precise information from the period following the Roman domination in the period of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages[4]. Probably some Lombard settlements were in Grana valley, or at least the neighboring countries.

Set on the front wall of the church of Santa Maria della Valle in Valgrana, we find a stone plaque that bears a pedunculate cross in a typical Lombard style. It has been hypothesized that the plaque was originally part of a sarcophagus that belonged to two spouses. In fact, next to the cross we find two “têtes coupées”. They probably represent the effigies of the guests of the sarcophagus. The depictions of “têtes coupées” also recall a typically Celtic practice of dark times. This practice consisted in beheading enemies and sticking their heads on poles placed outside the houses in an apotropaic function.

The "têtes coupées", carved in stone, and present in numerous examples in the western Alps, were placed on the threshold of homes or sacred places (as in the case of Santa Maria in Valgrana [7]) to ward off spirits and evil presences. The survivals of Celtic customs and habits, modified and absorbed in the Christian cult, are also clearly visible, for example, during the celebrations when the icons of the saints are carried in procession on the floats; the cult of San Magno, which we will talk about later, is an example. At the turn of the year 1000, the Grana valley was affected by the passage of the Saracens. However, it would seem to be only a legend that leads back to the wars between Christians "crusaders" and Saracens the origin of the toponyms of the middle valley (Vallone di Frise) "Sarasin" and "Crosats".

Between the early and late Middle Ages, the innovations of the Benedictine monks and the economic recovery.

A series of contingencies, for example the Saracen invasion, brought the population of the Alpine valleys to a contraction. This reduction in population also caused a loss at the crop level and large areas that were previously used for farming and cultivation not resisting the advance of vegetation, they were soon conquered by the woods [44]. Only the arrival of the Benedictine monks from Le Puy-en-Velay brought the valley back to its past glory, thanks to the reclamation works, the channeling of the water and the recovery of the high ground pastures. Between 1018 and 1176 was built "Santa Maria della Valle" near Valgrana, the oldest surviving church in the valley.

In the first years of the second millennium the power over the Grana valley (the Court of Caraglio with the castle, the district and the parish church, Valgrana, Montemale with the castle, with mountains, valleys and pastures and forests pertinent to them) was exercised by the Bishop of Turin. Whom, being very far from our valley, handed over the government to local lords.

Between the years 1165 and 1281 there was a strong expansionary policy on the part of the Marquises of Saluzzo increasingly interested in the Grana Valley.

In 1282, when all the rights that the ancient lords, the city of Cuneo and supporters of the Angevins had over the villages of the Grana valley, from Caraglio to Castelmagno, had been lost, there was a single lord: the Marquis of Saluzzo.

From this moment on and for a good part of the Middle Ages the history of the valley will be intertwined with the events of the Marquises of Saluzzo who became promoters of a great artistic rebirth of the valley commissioning various works and frescoes. The year 1486, which slightly precedes the discovery of the Americas by Christopher Columbus, and the conventional end of the European Middle Ages, is also the end of the Middle Ages for the Grana valley! In fact, that year the Duke Charles I of Savoy manages to invade the Marquisate, starting a series of clashes that will lead a few centuries later to the final seizure of power by the Savoy.

At the end of the Late Middle Ages, the western Alps experienced population growth, also due to the improved climatic conditions (the little glaciation that had characterized the climate of Europe in previous centuries was over). The problem therefore arose of the resources necessary for the sustenance of a larger population [15][41]. The populations of the Alps, equipped with vast pastures and mountain pastures, turned to pastoral activity, in order to exploit extensively but not intensively soils that are often sloping and with reduced production capacity. The delicacy of these ecosystems made it necessary to regulate. For this reason, the communities of the valley developed systems of rules that established rights and methods of use of land which, being placed above a certain altitude, belonged to the community [43].

At the same time, the development of this activity caused the institutionalization of a highly integrated economic system, since markets were necessary to exchange wool, dairy products and meat for those goods that are not locally produced. However, it is likely that the first production of the only cheese with Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) in the valley, Castelmagno cheese[18], dates back to these centuries and that it was born as a procedure to preserve small volume milkings.

After milking, small tomes were formed which, after being drained, were immersed in whey, which, by carrying out an antibacterial action, ensured conservation.

When the farmer had a sufficient quantity of curds to produce a shape, these tomes were crushed, salted and put into shape in the bundles that would give them the final appearance.

Castelmagno cheese [20].

It is considered the King of Cheeses, Castelmagno owes its name to the homonymous municipality of the Valley.

As already mentioned, its origin is very ancient: production probably began around the year 1000.

The first document that names the cheese is an arbitration award of 1277, which required the Municipality of Castelmagno to pay an annual fee to the Marquis of Saluzzo, in the form of Castelmagno instead of in cash.

Another historical document in which the prized cheese is mentioned is a decree of King Vittorio Amedeo II, who ordered, in 1722, the supply of forms of castelmagno to the local feudal lord.

All Castelmagno cheese has the wording "Mountain Product" with the blue label, but it can also have the mention of "Alpeggio" with the green label and Slow Food Praesidium when it is produced between May and October at over 1000 m of altitude.

Since 1996 Castelmagno has obtained the recognition of Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) which guarantees, through a production disciplinary, the unaltered maintenance of its characteristics and allows it to be recognized as a typical product of the upper Grana valley.

The production area corresponds to the municipalities of Monterosso Grana, Pradleves and Castelmagno.

Nowadays, the processing of this cheese takes four days, in which the curd is dipped in the whey before taking its final shape and being left to mature. After three months of maturation, Castelmagno looks like a semi-hard, dry and crumbly cheese. The rather fine rind is brownish-yellow, with darker variants. Furthermore, with the ageing the pasta has green veins due to a natural marbling. The particular flora that characterizes the meadows of the valley gives the cheese a unique taste and makes it a precious commodity, emblematic of the territory of which it is the expression. The production of Castelmagno cheese is part of a general protection and conservation of the environment and its landscapes, giving rise to a defence of the territory which is fundamental for the balance of the system in its entirety.

Starting from Caraglio going up towards the upper valley there are numerous tasting points, where it is also possible to buy this precious food. In the kitchen it is used melted to season potato gnocchi, but it presents its organoleptic properties well when eaten fresh accompanied by mountain honey.

Fig. 6. Castelmagno cheese

The sanctuary of S. Magno and the local religiosity

There is also an ancient link between pastoralism and the forms of religiosity characteristic of the Grana valley, many of which revolve around the mentioned sanctuary dedicated to San Magno, at about 1800 above see level. This saint is one of those legionary saints[24] who represent a typical trait of the religiosity of the South-Western Alps and who enter into complex systems of geographic and / or professional devotion. In the past, the sanctuary had considerable importance as a religious center, beyond the borders of the valley, in particular for those groups for which animal husbandry was an important source of subsistence. The saint was, and still is, invoked for the protection of livestock, and often the faithful who go on pilgrimage to the sanctuary collect pictures of the saint, which they then hang in the stables or at the entrance to the houses. In the Grana valley, the oldest evidence of a cult to this saint is the Allemandi chapel of the fifteenth century, which constitutes the oldest core of the sanctuary. The building reached its current form in the 18th century.

The Allemandi chapel [31], still existing and well restored, is located behind the main altar of the sanctuary. Generally referred to as the ancient chapel, it is instead a structure built in two distinct periods, where the primitive Allemandi chapel was enlarged by Botoneri, who modified its structure and above all the decoration. It is a small chapel preceded by a portico and protected by a heavy gate to prevent theft and looting[35]. The small building, built around 1475 in Gothic style and soberly executed, is attributed to this master Pietro da Saluzzo, author of other chapels in the valley. The church that incorporated the first chapel was built in 1514 and decorated by a certain Giovanni Botoneri, a Franciscan friar from Cherasco. The artist’s absence of any Renaissance technique makes it particularly valuable. The frescoes had as their main purpose the catechesis of the local population, poor and illiterate, who, thanks to the images, could become aware of what was narrated and described in the Gospels. In addition to the salient events of the Passion, death and Resurrection of Christ, saints particularly linked to local tradition are also depicted. In 1894 the chapel was the subject of excavations for the reconstruction of the floor, which brought to light several burials and ancient finds, including the tombstone now set in the rear wall of the sanctuary. Unfortunately, the neglect of those who carried out those excavations led to the destruction or loss of many of those precious finds

Always connected to the cult of S. Magno is the feast of the "Baía” held every 19 August, the feast day of the saint. The term "Baía" indicates a group of men united by shared values and led by the "Abà’’, often the oldest member of the group. On that day the company (made up of 12 men) parades around the sanctuary, wearing a uniform characterized by colored ribbons and hats with feathers and plumes. Each of the members of the Baía carries a halberd with them. It is probable that the now symbolic presence of weapons is what remains of the primary role of these companies, that is the maintenance of order, especially in those situations in which scuffles and quarrels were more likely, as could occur at the auction of the pastures of Castelmagno, which took place at the sanctuary on the feast day of the saint.

Fig. 7. The Sanctuary of San Magno during a starry night (credit Samuele Martino)

The Red Spinning Wheel of Caraglio

The Red Spinning Wheel of Caraglio was built between 1676 and 1678 on the initiative of Count Giovanni Girolamo Galleani [5], it was one of the first silk production plants in the Duchy of Savoy and throughout Europe. It housed the entire production chain of the yarn, from the cultivation of mulberry trees in the surrounding countryside for the breeding of silkworms to the processing and realization of the finished product, becoming the progenitor, together with the contemporary Venaria plant and a system of spinning mills built in Piedmont, for the following decades.

In 1857 the descendants of the Galleani family sold the spinning wheel to the Cassin family of bankers, following a crisis due to the Pébrine, or "pepper disease", which affected mulberry crops and the same silkworms throughout Europe and which led to the search for new cocoons in the Far East; it was probably in this period that the entire building took on the red color of the walls, hence the name "red spinning wheel".

Production continued until 1936, the year in which the spinning machine definitively ceased its centuries-old activity, a decision made necessary also following the new policy of economic self-sufficiency imposed by the fascist regime which promoted the production of alternative yarns such as viscose and moleskin, derived from cotton grown in the Italian colonies of Africa. Since then the spinning wheel saw an inexorable decline which culminated in the transformation into a military barracks during the Second World War and which also saw it as the target of aerial bombardments which damaged it, depriving it of one of its six perimeter towers.

Despite decades of neglect, in 1993 the Council of Europe defined the spinning wheel as "the most distinguished historical-cultural monument of industrial archeology in Piedmont" and in 1999 the entire complex was acquired by the Municipality of Caraglio with the intention of recovering it.

Subsequently it was completely renovated becoming the oldest still preserved silk factory in Europe and one of the few in Italy to have been recovered as a museum [13][14]; it promotes cultural events of reference for the territory and hosts the Piedmontese Silk Factory Museum, which boasts a complete set of faithful reproductions of functioning wooden machinery reconstructed on the basis of documentary sources preserved in the historical archives of Cuneo and Turin. Since 2002, the Filatoio Rosso di Caraglio has become part of the Castelli Aperti del Basso Piemonte (Open Castles of Lower Piedmont) system.

Occitan or Provençal culture, between language, music and cultural centers.

The area of the Grana valley belongs to the historical area where people still speak the language d’oc or Provençal which, according to the historical periods, extended over more or less vast areas straddling the Alps, southern France and the Pyrenees. Among the neo-Latin languages, the language of oc was one of the first to express, around the 11th-12th century, its own literature, fundamentally linked to themes of a religious or spiritual nature, or to the society of the feudal courts that dotted the territory between the French Midi and Monferrato, passing through Provence[38].

The disappearance of that world to which it was intrinsically linked also marked the decline of the language of oc as a language of literary use. Interest in this language re-emerged from the second half of the nineteenth century, with the circle of Félibrige (between Aix-en-Provence and Marseille), which recognized its value and relaunched its use. Among the main members of this intellectual milieu we must remember Frédéric Mistral who obtained the Nobel Prize for literature, precisely with a collection of texts in the Provençal language, entitled Mireia (1904). Having not received formal language recognition for a long time, Occitan / Provençal developed local forms, due to contamination with other languages (Spanish, French, Italian), as well as the linguistic substrates prior to the Latinization of these territories. In the case of Val Grana and the neighboring valleys, the language still spoken is the language of OC in its vivaro-alpine variant. About its enhancement and transmission, it is guaranteed by the Coumboscouro Cultural Center (the only reality in Italy to have given life to a school experience in this language) and by the "Detto Dalmastro’’ Center which, in different ways and perspectives, both have tried to safeguard this rich heritage. In Italy, the eighties saw a progressive awareness of the value of this language, with publications, conferences on the subject and, at the same time, the development of festive occasions. Throughout the Provençal / Occitan area it is worth noting the presence of choral or musical ensembles [12] which, placing themselves between philological reconstruction and hybridization with other genres, have made the musical creations linked to this language and its territory usable. In particular, the choirs of L’Escabot and La Cevitou, the pop-rock of Lou Dalfin and the Mediterranean tones of Marlevar were born in the Grana valley.

Fig. 8. The Sanctuary of San Magno was founded in 1475 on a pre-Christian pagan place of worship, as evidenced by the Roman altar dedicated to Mars, now kept in the church.

The Grana valley also had its "agronomist parish priests”[9]. We can remember among these figures that of Don Beltramo, parish priest of Caraglio in the times of the Second World War. Don Beltramo was dedicated to the cultivation of his own vineyard on the slopes of the hill of the town’s Castle. Another interesting figure was Don Giuseppe Martini who was chaplain of Pontebernardo and lived between the 17th and 18th centuries. In addition to his activity as a chaplain, Martini devoted himself to his great passion for geometry and surveying calculations. Not only did he also dedicate himself to astronomical calculations and in particular to the determination of useful numbers for calculating mobile holidays and days of the year. He studied the epact, the gold number and the indication. He also studied the determination of the meridian which was useful for the construction of many sundials. He was called upon to build sundials in various towns in the Cuneo valleys and one was still visible in the Chiappi hamlet, near Castelmagno.

The time, sundials and clocks in general were held in high esteem by the Alpine communities between the 17th and 18th centuries. In the statutes of Valgrana [42] and in the accounting documents we find information on the amount of the salary of the person in charge of regulating the clocks. His salary was about double that of a normal municipal messenger.

Justification for inscription

Comparative analysis - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-25 12:15:05

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

The designated geographical area is a deep intertwining of nature and culture, its biodiversity and deep historical roots live the most genuine symbiosis between human evolution and the extreme alpine environment, in fact the Grana Valley, Castelmagno and the Fauniera hill are a perfect candidate for the ’Heritage, its geographical position and the particular geological conformation of the Alps, combined with the biosphere, make the naturalistic heritage of the place exceptional, also thanks to the almost absent anthropization of the upper valley.

Valle Grana represents one of the last places of dark and uncontaminated sky in the Western Alps [19]. The Alpine arc creates a natural barrier that mitigates the harmful effects coming from the neighboring areas, furthermore the geological conformation of the valley is closed for most of the territory included in the buffer zone, effectively avoiding the dispersion of light from the ground in the villages present throughout the territory.

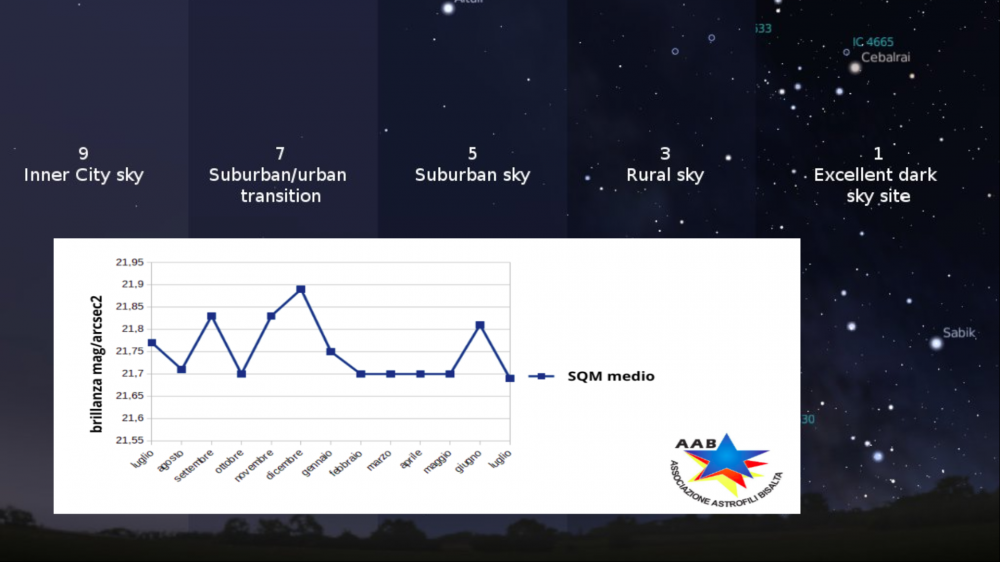

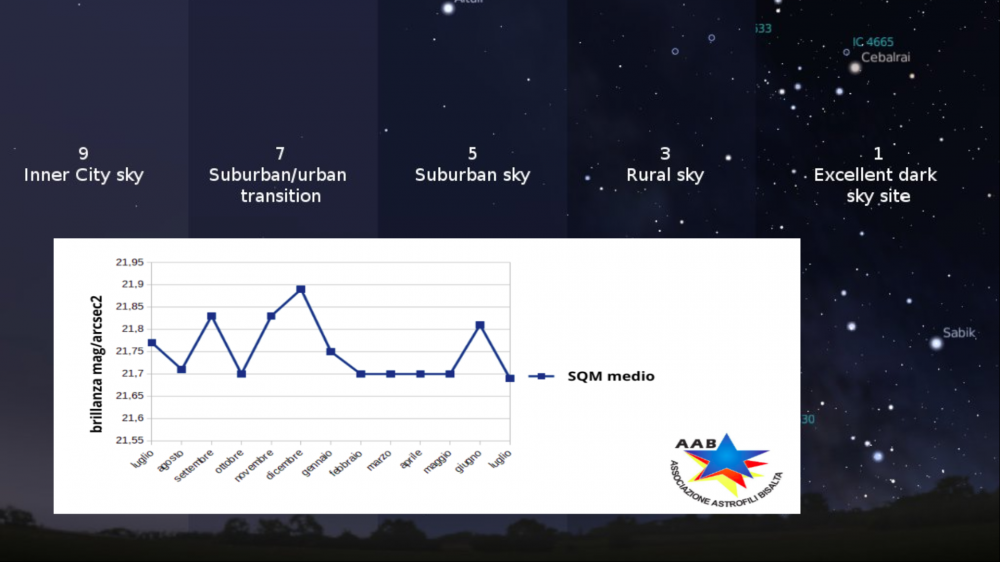

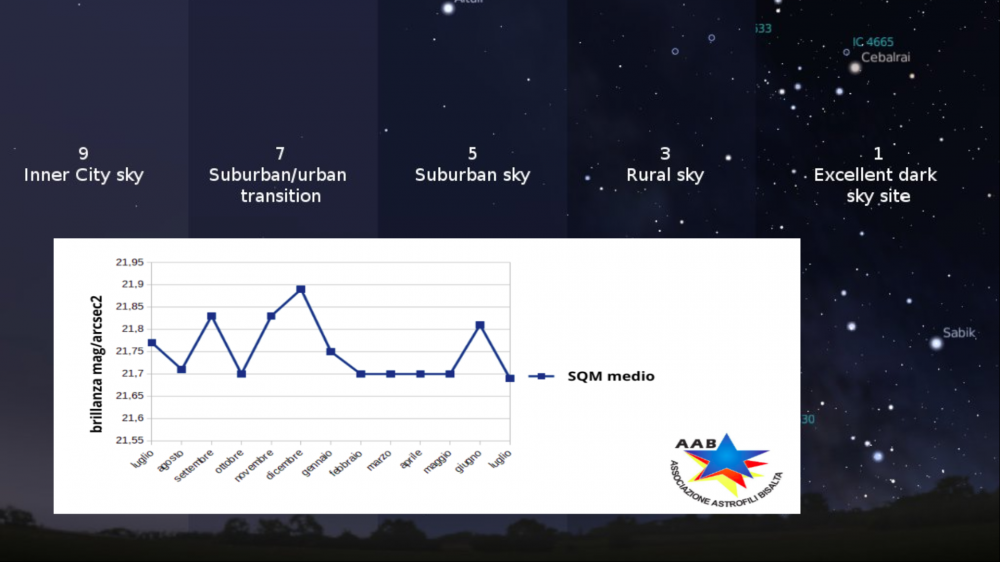

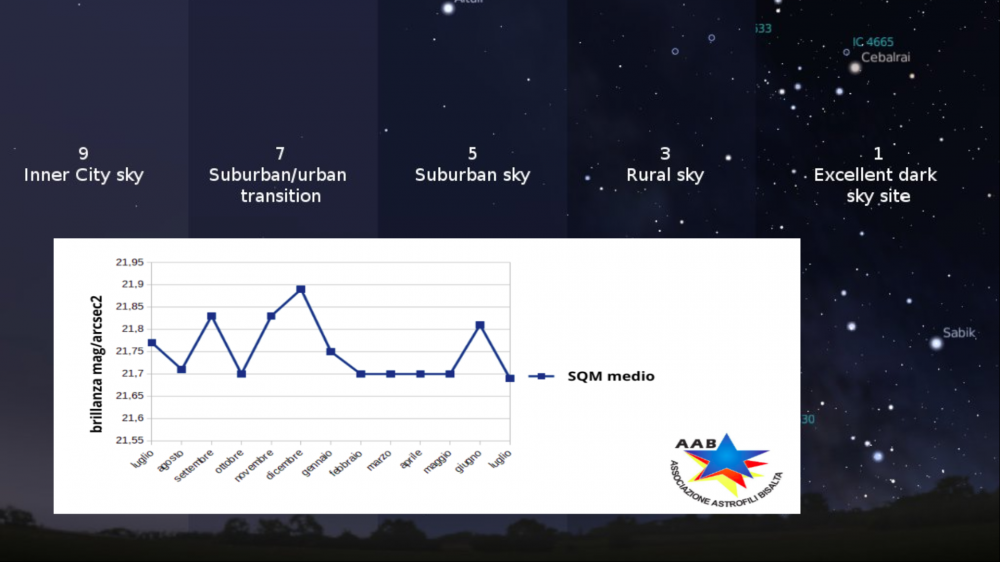

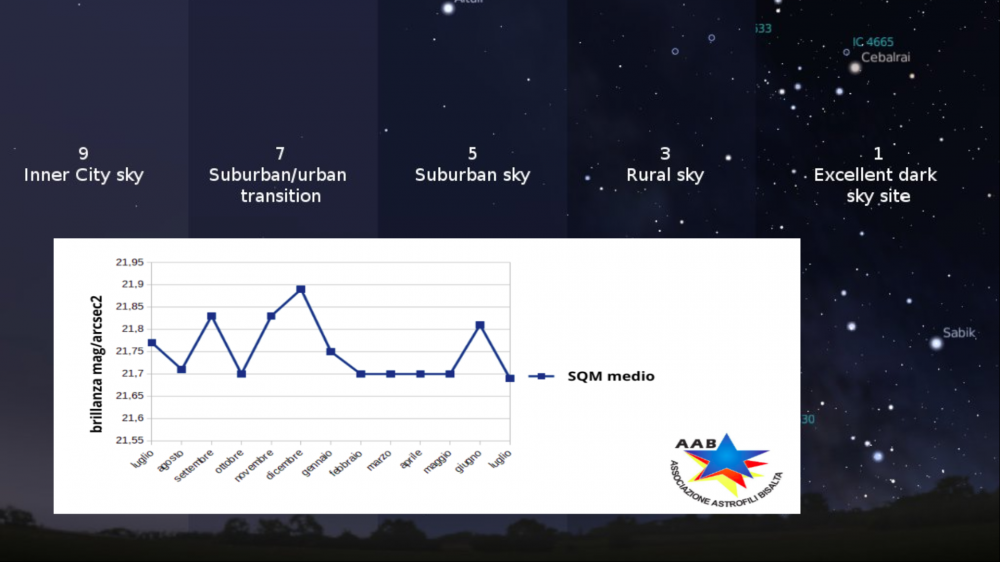

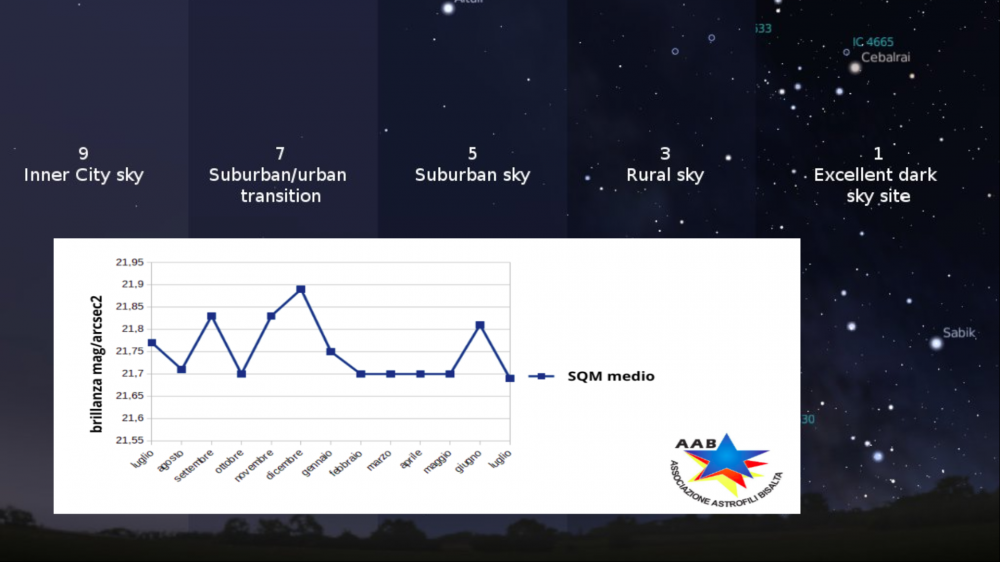

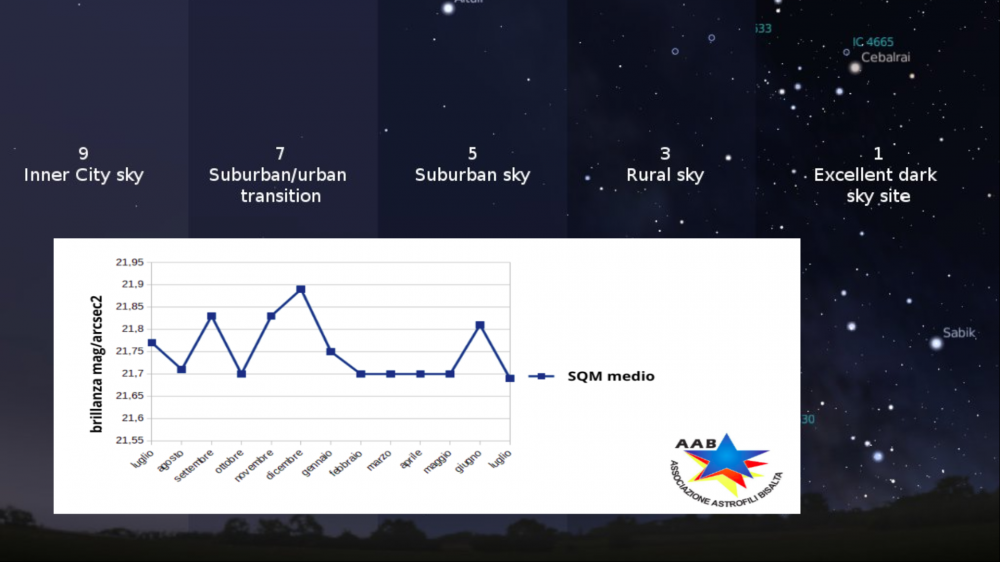

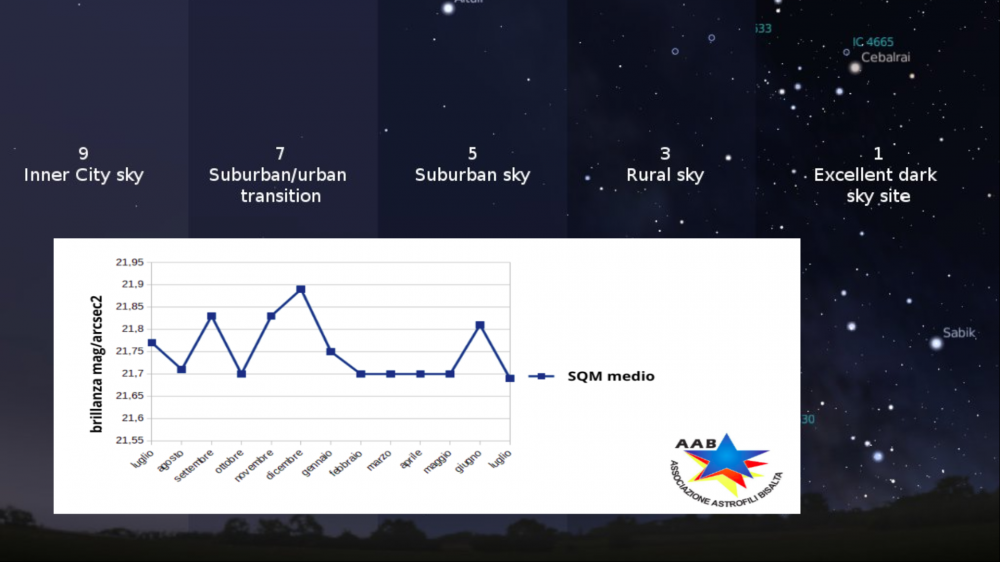

Fig. 9. The effects of light pollution, and the plot with the zenithal luminance value during the years 2019-2020

With a difference in height of 1900 m, the valley has several sites that, depending on the season, are taken into consideration for astronomical observations of the dark sky. During the summer, the upper valley area and Colle Fauniera are half for the users of the starry sky and amateur astronomers from the polluted plain. Its altitude of 2400 m above sea level allows a clear sky and free from atmospheric dust, not present at these altitudes. In the winter period, the possibility of reaching the hill is no longer possible, therefore amateur astronomers and photographers stop at 1700m, where the sanctuary of Castelmagno is located, also an area of astronomical interest, due to its high altitude and the lack of pollution. The valley has always presented a difficult anthropization factor for which the sky has resisted until today in its integrity.

As a comparative method for classifying the sky of the upper Grana valley, measurements were repeated during a calendar year to actually evaluate the variation in the quality of the dark sky, the measurements led to estimate average SQM (Sky Quality Meter) in 21.77 mag / arcsec² with peaks of 21.90 mag / arcsec², this led us to estimate the sky at the same value as desert sites such as Namibia or in South America as in Chile. In recent years, interest in the valley has grown from an astronomical and astrophotographic point of view, making it de facto a popular destination for astronomy and the dark sky. The summer views of the Alps and the snow-capped winter peaks represent a breathtaking sky-landscape heritage.

These values are comparable with those of the international dark sky reserve certified by the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) for the neighbouring French park Alpes Azur Mercantour.

They are better than the "Star light stellar park Saint Barthelemy" certified by the Starlight Foundation in Valle d’Aosta (Italy).

Fig. 10. Milky Way observed from Colle Fauniera (credit Federico Pellegrino)

Fig. 11. Milky Way observed from Colle Fauniera (credit Federico Pellegrino)

Integrity and/or authenticity - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-25 09:56:42

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Criteria under which inscription might be proposed - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-25 12:35:59

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Criterion (v). Man has been inextricably linked to the territory of the Grana valley and to Castelmagno since the Neolithic period. This bond is testified by the Occitan culture which is rooted in the population and traditions of the valley, and has endured over the centuries as an identifying feature of the people who live there. The tradition of cheese production in Castelmagno, which extends back to the Middle Ages, and its origins embody the resistance and adaptation of man to an extreme mountain environment.

Criterion (vii). The Grana Valley is a place of undisputed beauty both for the landscape and the almost pristine quality of the night sky, where the Alps frame an incredible panorama.

Criterion (ix). The alpine habitat of Valle Grana provides a superb example of resistance and recovery in habitats heavily exploited by man in the past. The gradual natural restoration of its conditions includes the reforestation of areas completely deforested in the past, including some endemic ones.

Suggested statement of OUV - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-25 12:37:19

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

The Grana Valley is a historical and cultural treasure chest combining a spectacular natural landscape, distinctive flora and fauna and geology, and an almost pristine night sky.

The Grana valley and the sites of Castelmagno and Colle Fauniera represent a unique blend of history [32][36], culture [3] and biodiversity. The Alps in the upper valley are an example of a mountain habitat that has coexisted with man for millennia.

The Occitan cultural and linguistic roots that are based in ancient pre-Roman history with the Celtic Ligurian populations who inhabited the valley, the culture of Castelmagno cheese and its origins represent the resistance and adaptation of man to extreme mountain systems, make this in fact, a candidate with a unique heritage.

This combination of factors and the incredibly beautiful night sky make the deep bond that the night sky and astronomy represent with human evolution in the valley indissoluble.

State of conservation and factors affecting the property

Present state of conservation - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-25 12:57:10

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

The municipality of Castelmagno has remained a geographical area where you can still admire a sky almost completely devoid of light pollution.

Factors affecting the property - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-25 13:03:52

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

The area in question does not present problems related to human development. Despite this, a collaboration plan is being implemented with local institutions for the protection and retrofitting of the lighting structures.

Protection and management

Ownership - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-25 13:05:28

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Mixed property, state and municipal land. Some areas have private pastures.

Means of implementing protective measures - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-07 11:00:48

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Piedmont regional law No. 3 of 9 February 2018 for the fight and prevention of light pollution [34].

Existing plans - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-25 13:10:38

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

It is expected to further increase activities related to astronomy within the area, and to implement an energy and light pollution redevelopment project through further retrofitting and shielding. An evaluation is also being carried out of several places nominated for the construction of observatories and for activities aimed at the public such as tourism and training in science.

Visitor facilities and infrastructure - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-25 13:27:58

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Museum and exhibition areas are located throughout the Grana Valley. In particular, the Filatoio di Caraglio houses the important Museum of the Piedmontese silk factory.

There are alpine refugee accommodation facilities in the upper valley, and hotel and restaurant facilities along the lower-middle valley.

Also present are syndicates whose activities reflect the practicalities of the territory’s role in the agri-food sector.

Presentation and promotion policies - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 7

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-25 15:30:55

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Tourism is expanding, especially linked to alpine hiking and trekking in general. The valley has many events focused on astronomy and scientific dissemination.

The fact that the Grana valley had no direct outlet with neighboring France has preserved it, in the recent past, from the interests of mass tourism. Consequently it has no ski lifts and no current exploitation of land for the creation of “holiday villages”. This lack of interest has preserved the natural environment but also triggered a strong abandonment of the territory and progressive depopulation, especially between the 1970s and the 1990s. Only in the last twenty years have we witnessed a rediscovery of the valley by tourists seeking authentic cultural experiences, foods and wines. This has led to a new influx of inhabitants and new businesses focused upon agriculture or hospitality.

The Grana valley’s flagship product, Castelmagno cheese (the “King of cheeses”), is exported all over the world and produced only in the three municipalities of the upper valley as per the DOP regulations. Alongside this, the Slow Food presidium works to promote the multifaceted nature of the region by linking agrictural products to the culture of the territory that generates them. These include garlic from Caraglio, black truffle from Montemale, Potato Piatlina and Ciarda, and saffron from Valle Grana. These are just some of the products protected by syndicates, produced by farms, offered in the premises of the Valley and valued by cultural associations. They have allowed the territory to grow by telling the world about itself.

Mountain biking

The Grana Valley is a popular venue for cycling. Over the years two important competitions have developed: the Rampignando and the Chamin Classic. The Rampignando is a MTB cross-country-skiing track starting from Bernezzo that presents cyclists with a challenging 46.7 km loop and includes 1100 m of altitude difference. Every year, the Rampignando leaves kilometers of clean trails ready to be traveled by MTB enthusiasts. The Chiamin classic is a 34km-long well-marked route with yellow tracks that leads up to 1430 m in altitude.

The Munteben to Muntumal is a third MTB itinerary comprising a series of permanent and well-marked tracks. The route can be varied, with distances from 10 to 50 km available, suitable for all technical and training abilities. For some years now, a non-competitive MTB ride has been organized through these dirt roads and paths in Montemale; the program usually includes an easier course of 12 km and a more difficult one of 30 km.

The curves and gradients of the Grana Valley have been made famous by the countless professional cyclists who have tackled them since the 1930s. From spring to autumn the roads are continually furrowed by competitive and non-competitive cyclists who try their hand at the challenges this territory can offer, including the tiring climb to Colle Fauniera, at the top of which stands the statue of Marco Pantani, erected in memory of the famous feat he accomplished here during the Giro d’Italia in 1999.

The annual Granfondo Fausto Coppi competition, started in 1987, attracts participants from 62 different nations.

Documentation

Most recent records or inventory - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-25 15:45:29

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Associazione Astrofili Bisalta

Bibliography - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-07 19:05:34

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

[1] AA.VV., 1991 – Corine biotopes manual. Habitats of the European Community. Office for Official Pubblications of European Communities, Luxemburg-2: 300 pp.

[2] AA.VV., 1996 – Interpretation manual of European Union Habitats. Europ. Comm. DG XI Environment, nuclear safety and civil protection: 145 pp.

[3] AA.VV., Indagine storico-culturale sulla valle grana, Regione Piemonte, Cuneo, 1984.

[4] AA.VV., Caraglio e l’arco alpino occidentale tra antichità e Medioevo, L’Arciere, Cuneo, 1989

[5] AA.VV., Nascita del Setificio Moderno. Il Filatoio Galleani di Caraglio. Scritti in onore di Luigi Galleani d’Agliano, SBNITICCUTO01887196.

[6] AESCHIMANN D., LAUBER K., MOSER D. M., THEURILLAT J. P., 2004 Flora alpina.Zanichelli. Bologna

[7] ARNEODO D., AUDELLO B., DABBENE V., DADONE G, DEIDDA D., ROSSO A., Santa Maria della Valle: 1000 anni di storia, in «Quaderni dei Laboratori di ricerca storica delle valli Grana e Stura», n° 5, 2020.

[8] BALDI R., Antropomorfi schematici in Valle Grana – Schematic anthropomorphous Rock Art Western Alps – Italy, in «Bollettino del Centro Studi e Museo d’Arte Preistorica di Pinerolo, Anno V-VI», n° 7-8, 1992

[9] BRUNELLO P., Acquasanta e verderame. Parroci agronomi in Veneto e Friuli nel periodo austriaco (1814-1866), Cierre Edizioni, Verona, 1996.

[10] CAMERANO P., GOTTERO F., TERZUOLO P., VARESE P., 2004 – Tipi forestali del Piemonte. Regione Piemonte. I.P.L.A. Blu edizioni . Torino. 204 pp.

[11] CAVALLERO A., ACETO P., GORLIER A., LOMBARDI G., LONATI M., MARTINASSO B., TAGLIATORI C., 2007. I tipi pastorali delle Alpi piemontesi. Alberto Perdisa Editore, Bologna

[12] CESTOR É., Regain de la création musicale en Oc au XXIème siècle, in «La pensée de midi», n° 31/2 2010, pp. 165–168

[13] CHIERICI P.(a cura di), Fabbriche, opifici, testimonianze del lavoro: storia e fonti materiali per un censimento in provincia di Cuneo, Torino, 2004, SBNITICCUTO01328973.

[14] CHIERICI P.(a cura di), Un filo di seta. Le fabbriche magnifiche in provincia di Cuneo, Cuneo, Edizioni Nerosubianco, 2007, SBNITICCUTO01635340.

[15] DEIDDA D., Preminenza e crisi dell’attività di allevamento nelle Alpi sud-occidentali tra il XIII e il XVI secolo, in «Draios e Viol», 2 2009

[16] DESTRO A., L’ultima generazione : confini materiali e simbolici di una comunità delle Alpi marittime, FrancoAngeli, Milano 1984

[17] DURANDI J., Il Piemonte cispadano antico, Stamperia Gianbattista Fontana, Torino, 1774

[18] FANTINO A. Mappatura Castelmagno D.O.P. in «Saperi e Sapori in valle Grana» Associazione La Cevitou, 2019

[19] FALCHI F., CINZANO P.,DURISCOE D., KYBA C., CHISTOPHER C. M., ELYIDGE Christopher D., BAUGH K. B, PORTNOV BORIS A., RYBNIKOVA NATALIYA A. and FURGONI R. The new world atlas of artificial night sky brightness. Science Advances vol 2 n. 6 - American Association for the Advancement of Science 2016

[20] Ferrari M., Eandi C., Bernardi E., Alla corte di re Castelmagno, Cuneo, Primalpe edizioni.

[21] FRASSON F., Il guerriero ligure nei frammenti di Posidonio di Apamea, in «Ex fragmentis per fragmenta historiam tradere. Atti del Convegno, Genova, 8 ottobre 2009», pp. 149-150

[22] GALLINO B., PALLAVICINI G., 2000 – La vegetazione delle Alpi Liguri e Marittime. Blu edizioni.Peveragno

[23] GIORCELLI BERSANI S., L’impero in quota. I Romani e le Alpi, Einaudi, Torino, 2019

[24] ISNART C., Les saints légionnaires dans les Alpes du Sud in «Le Monde alpin et rhodanien. Revue régionale d’ethnologie», n° 31, 1, 2003 pp. 247-248.

[25] MENNELLA G., La Quadragesima Galliarum nelle Alpes Maritimae. In «Mélanges de l’’Ecole francaise de Rome. Antiquité», n°1, 1992.

[26] MONDINO G.P., 1960 – Su tre entità nuove per il Piemonte: Juniperus phoenicea L., Veronica jacquinii Baumg., Linum narbonense L. Nuovo Giorn. Bot. It., 67: 252-253.

[27] MONDINO G.P., 1989 – I querceti a bosso delle Alpi Cozie meridionali (Valli Grana e Maira). Riv. Piem. St. Nat., 10: 69-92.

[28] MONDINO G.P., 2001 – Querceti basifili di roverella e xerobrometi della bassa Valle Grana (Alpi Cozie). Riv. Piem. St. Nat., 21: 103-122.

[29] MONDINO G.P., 2003 – L’evoluzione nell’ultimo quarantennio della vegetazione in Valle Grana (Alpi Cozie). Riv. Piem. St.Nat.24,2003: 67-203.

[30] MONDINO G.P. et al. (IPLA), 2007 – Flora e vegetazione del Piemonte. Regione Piemonte

[31] Gino Musso G., Il Santuario di San Magno, Cuneo, Primalpe, 2005, ISBN88-88681-42-6.

[32] PEROTTI M., Repertorio dei monumenti artistici della provincia di Cuneo, 1986

[33] PIGNATTI S., 1979 – I piani di vegetazione in Italia. Giorn. Bot. Ital., 113: 411-428.

[34] REGIONE PIEMONTE, legge regionale 3/2018 “Modifiche alla legge regionale 31/2000 (Disposizioni per la prevenzione e lotta all’inquinamento luminoso e per il corretto impiego delle risorse energetiche

[35] RIBERI A. M., RAM. Repertorio di antiche memorie, Vol. 1-2-3-4, Primalpe, Cuneo, 2002

[36] RISTORTO M., Valle Grana nei secoli, Ghibaudo, Cuneo, 1977

[37] RUGGLES C., Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy in the context of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention 2017

[38] SUMIEN D., Classificacion dei dialèctes occitans, in «Revista D’Oc. Linguistica Occitana», 7 2009, pp. 1–55

[39] SINDACO R., MONDINO G.P., SELVAGGI A., EBONE A., DELLA BEFFA G:, 2003. Guida al riconoscimento di ambienti e specie della direttiva Habitat in Piemonte. Regione Piemonte. I.P.L.A.

[40] SINDACO R., SELVAGGI A., SAVOLDELLI P. - REGIONE PIEMONTE,2008 La Rete Natura 2000 in Piemonte - I Siti di Interesse Comunitario – Integrazione on-line: Zone di Protezione Speciale per gli uccelli- Sindaco A., Savoldelli P. - Regione Piemonte - 2017

[41] VIAZZO P., Upland communities: environment, population and social structure in the Alps since the sixteenth century, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989

[42] VIOLA G., Valgrana 1415-2015. Sei secoli di storia di un paese attraverso i suoi Statuti, il Catasto e l’archivio, Primalpe, Cuneo, 2015.

[43] VIOLA G., Dai Beni Comuni ai Beni della Comunità. Declino e monetizzazione dei beni comuni nelle valli Grana e Stura di Demonte fra i secoli XVII e XIX, in «Studi Piemontesi», n. 44, 1 2015, pp. 125–134

[44] WICKHAM C., Pastoralism and underdevelopment in the Early Middle Ages, in «L’uomo di fronte al mondo animale nell’alto Medioevo», CISAM, Spoleto 1985, pp. 400–451

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-05-17 13:21:05

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Italy / Western Alps

State/Province/Region - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-07 19:06:52

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Italy/Cuneo/Piedmont

Name - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-05-17 13:21:58

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Fauniera Pass, Municipality of Castelmagno, Grana Valley, (Cottian Alps)

Geographical co-ordinates and/or UTM - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-05-17 13:22:22

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Geographical area that includes Colle Fauniera, the sanctuary of Castelmagno,

and the municipal area of Castelmagno.

Colle Fauniera: 2481 m above sea level 44 ° 23′08.56 ″ N 7 ° 07′18.79 ″ E

Castelmagno Sanctuary: 1760 m above sea level 44 ° 17 ’46.12 "N - 7 ° 17’ 13.24" E

Municipality of Castelmagno: from 2,600 to 700 m above sea level.

long axis (about WE) 44 ° 23′08.56 ″ N 7 ° 07′18.79 ″ E at 44 ° 24’49.5 "N 7 ° 15’00.6" E

short axis (about NS) 44 ° 26’02.3 "N 7 ° 12’58.9" E at 44 ° 22’49.9 "N 7 ° 13’03.2" E

Buffer Zone

Geographical area that includes the Grana Valley (Cottian Alps)

Grana Valley: from 2600 to 500 m above sea level.

Long axis (approx. W-E): 44°23′08.56” N,7°07′18.79”E to 44°25′59.3” N, 7°29′00.5”E

Short axis (approx. N-S): 44°26′02.3” N, 7°12′58.9” E to 44°22′49.9”N, 7°13′03.2”E

Maps and plans,

showing boundaries of property and buffer zone - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-05-27 13:01:16

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Fig. 1. a) Google aerial view of Piedmont area. b) Night view of piedmont with buffer and core zone. c) Grana Valley with boundaries of the Core and Buffer Zone. d) Core Zone: Municipal area of Castelmagno. Blu line identifies Cuneo district, the yellow line the Buffer Zone, the green one the Core Zone.

Area of property and buffer zone - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-07 19:07:13

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

Core Zone: 43,31 km²

Municipality of Castelmagno, Colle Fauniera

Buffer Zone: 97 km²

Municipality of: Caraglio, Montemale, Valgrana, Monterosso Grana and Pradleves.

Description

Description of the property - InfoTheme: ‘Windows to the universe’: Starlight, dark-sky areas and observatory sites

Entity: 196

Subentity: 1

Version: 9

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-06-25 11:58:44

Author(s): Federico Pellegrino, Barbara Barberis, Alberto Cora, Arduino Rosso, Stefano Macchetta, Stefano Melchio, Gabriele Orlandi, Richard Laurence Smart

The Valle Grana is a valley in the province of Cuneo, Piedmont, northern Italy.

It takes its name from the Grana stream, a tributary of the Maira which flows through the valley.

The territory of the municipality of Castelmagno and the Fauniera pass, set in the upper Grana valley, are part of a unique alpine landscape characterized by a starry sky, almost uncontaminated.

With an area of 43 km², this landscape represents a unique heritage from a historical, naturalistic and astronomical point of view.

The central area is divided into two distinct sites lying in the municipality of Castelmagno:

- Fauniera Pass

- Sanctuary of Castelmagno

These areas are located at the apex of the buffer zone which then extends with a territory of about 130 km² up to the bottom of the valley with the municipality of Caraglio.

The territory of the Grana Valley extends from the Po Valley to the Alpine peaks that reach 2600 m. It is located in the southwestern Alps, a bio-geographical region close to the Mediterranean area and renowned for its high level of biodiversity and for hosting many endemic species.

Fig. 2. Landscape of the Grana Valley

Geological and geo-morphological framework

The valley with a development of about 25 km and east-west direction, sits entirely on rocks belonging to the Pennidic region. Much of the valley development, from Caraglio to the Sanctuary of San Magno is divided into the Piedmontese area of calcescisti with Green Stones (with the only exception of Pradleves). A little west of the Sanctuary there is the tectonic contact with the Brianzonese area, in particular the base represented mainly by the Permian acid volcanites or by its metamorphic derivatives.

In the higher part of the valley, near Colle Fauniera, the sedimentary covers of the Brianzonese also emerge, little or not at all metamorphosed as in most of the southern Brianzonese, represented by limestone, dolomitic limestone and Triassic carneole.

As mentioned above, to the south and south-west of Pradleves, thanks to the presence of a small tectonic window, the Inland Massif of Dora Maira emerges in a very limited range, represented mainly by gneisses and micascists.

From a geomorphological point of view, the valley can be divided into 3 different areas. The valley floor, from Caraglio to Monterosso Grana, where the morphology linked to glacial erosion has been partly hidden by the fluvial sediments that have filled the valley floor, creating large river terraces and drowning any moraines present. From Pradleves to Campomolino the valley has a typically fluvial current morphology, where the glacial forms have been eroded in favor of a particularly carved valley and deep side valleys. From Campomolino upwards, especially starting from the Sanctuary of San Magno, the valley has wide open spaces shaped by the feeding area of the Pleistocene glaciers and by circus glaciers.

Geology of high Grana Valley

As can be seen from the study of the geological map of Italy, Foglio Argentera - Dronero, near the Sanctuary of San Magno there is the tectonic contact that separates the Calcescisti Zone (to the north-east) from the Brianzonese Zone (to the south-west). This continues towards the SE on the left side of the valley and then develops into the Valloriate valley (Valle Stura) and towards the SW in the Sibolet Valley, emerging along the slopes of Mount Tibert and continuing towards Canosio and Valle Maira.

The Brianzonese area here in the upper Grana valley is represented, as anticipated in the framework, both by the base of Hercynian origin and by the Mesozoic sedimentary coverings attributable to the Tethys ocean. Using the valley road as a reference, from the Sanctuary to Ponte Fonirola, under the Rocca Parvo, where there are no glacial or detrital deposits, some schists with quartz and sericite and quartzites emerge, both metamorphic rocks of the Permian and Carboniferous, therefore attributable to the so-called “Ercinico’’ base, which therefore constituted the Pangea continent and which already show an initial phase of rift and a marine ingress or fluvial and / or shallow sea deposits, attributable to the first phases of opening of the Tethys Ocean.

The peculiarity of this succession, common to the whole Brianzonese area, is the large stratigraphic gap of the Lower and Middle Jurassic, evidence of a general phase of emergence and subaerial erosion.

The Brianzonese sedimentary succession is considered to be the testimony of a basin within a passive margin, that is, the margin of a continent subject to rift. The sedimentary succession is considered as a flap of the European paleo-margin. The current tectonic limits that divide the different zones derive from the Mesozoic extensional limits and have allowed the crust to thin out during the extensional phase, and then reactivate as sliding planes during the Alpine orogeny.