Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Stockholm Observatory (until 1931), Sweden

Format: IAU - Outstanding Astronomical Heritage

Description

Geographical position - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-28 14:10:35

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Stockholms Observatorium, Observatorielunden, Drottninggatan 120, 113 60 Stockholm, Sweden

See also: 052 Saltsjöbaden Observatory (since 1931), Stockholm-Saltsjöbaden, Södermanland, Sweden

Location - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-28 15:49:11

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude 59°20’30’’ N, Longitude 18°03’17’’ E, Elevation ...m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-28 14:09:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

050

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 19:11:37

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

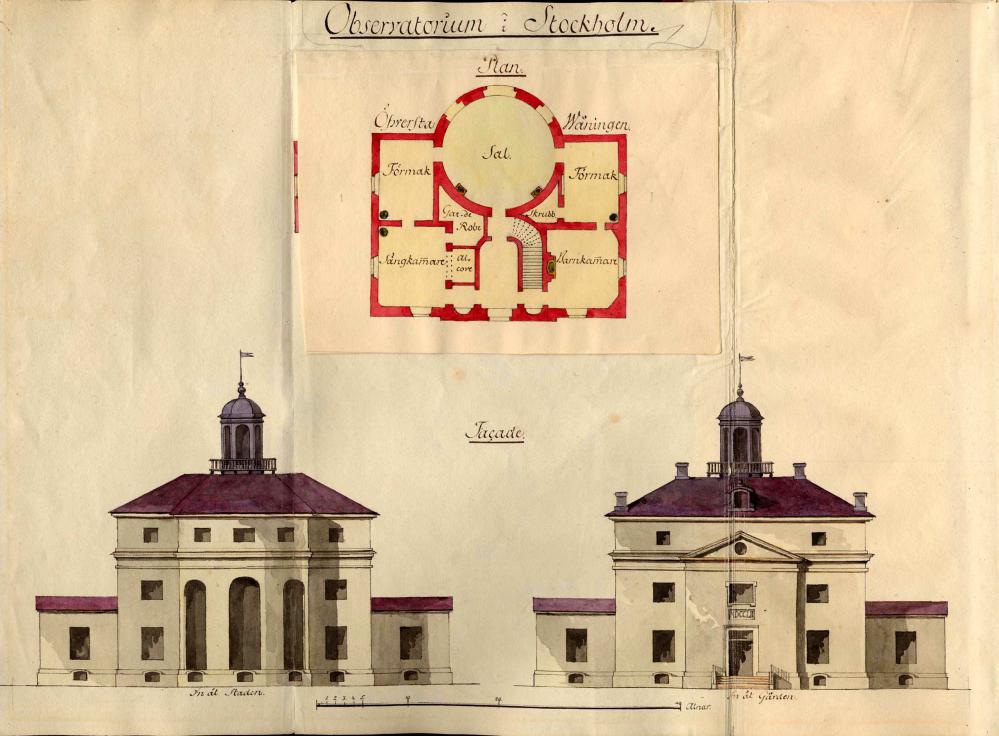

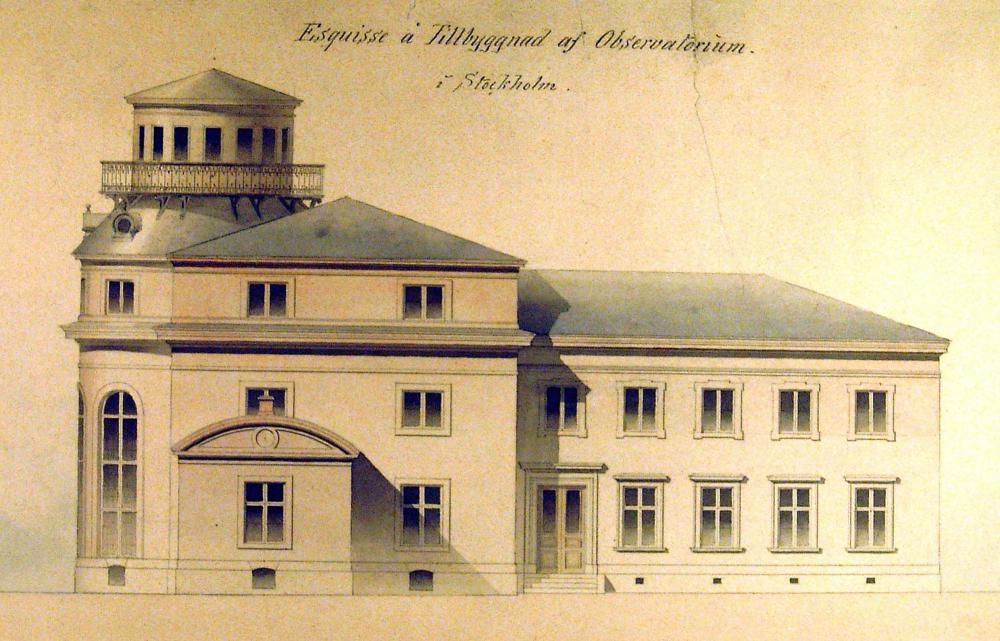

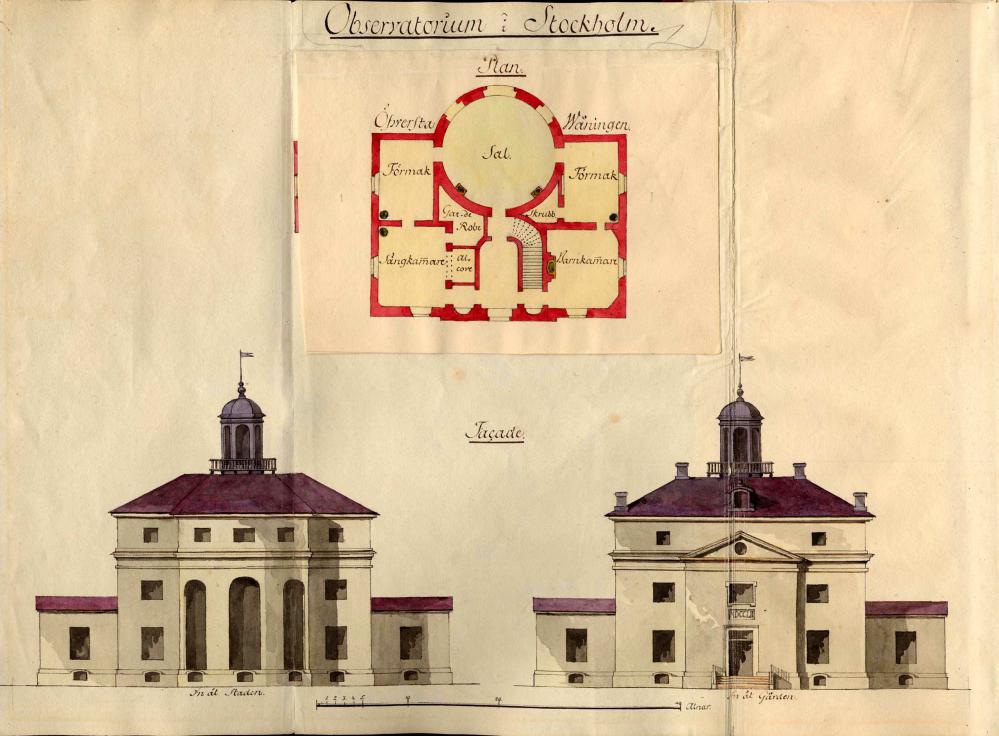

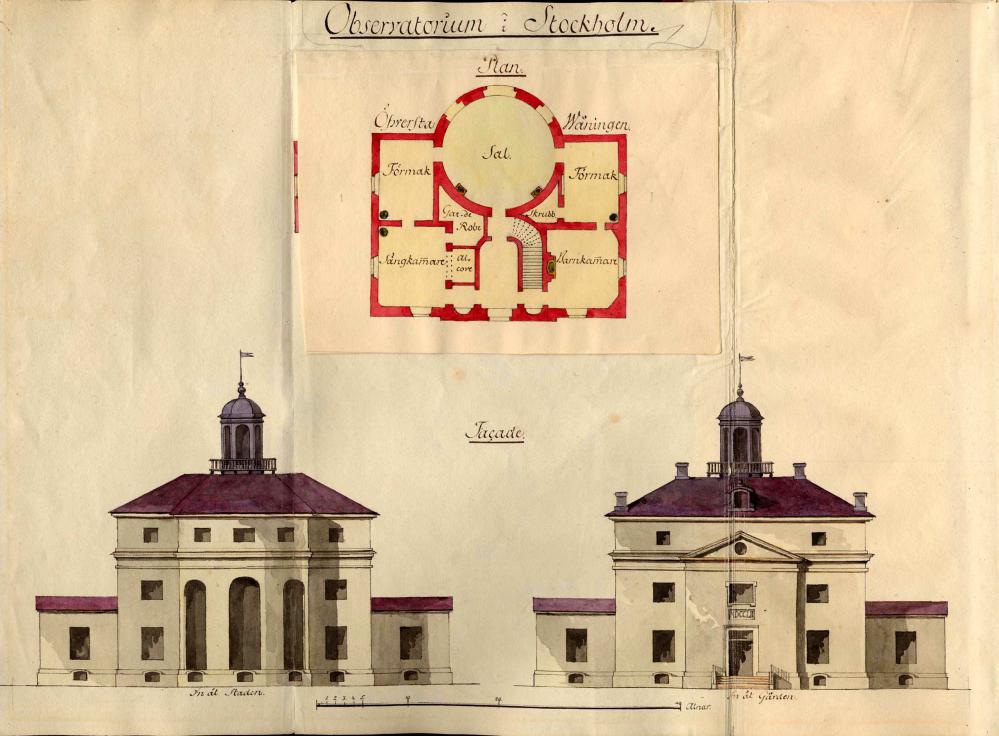

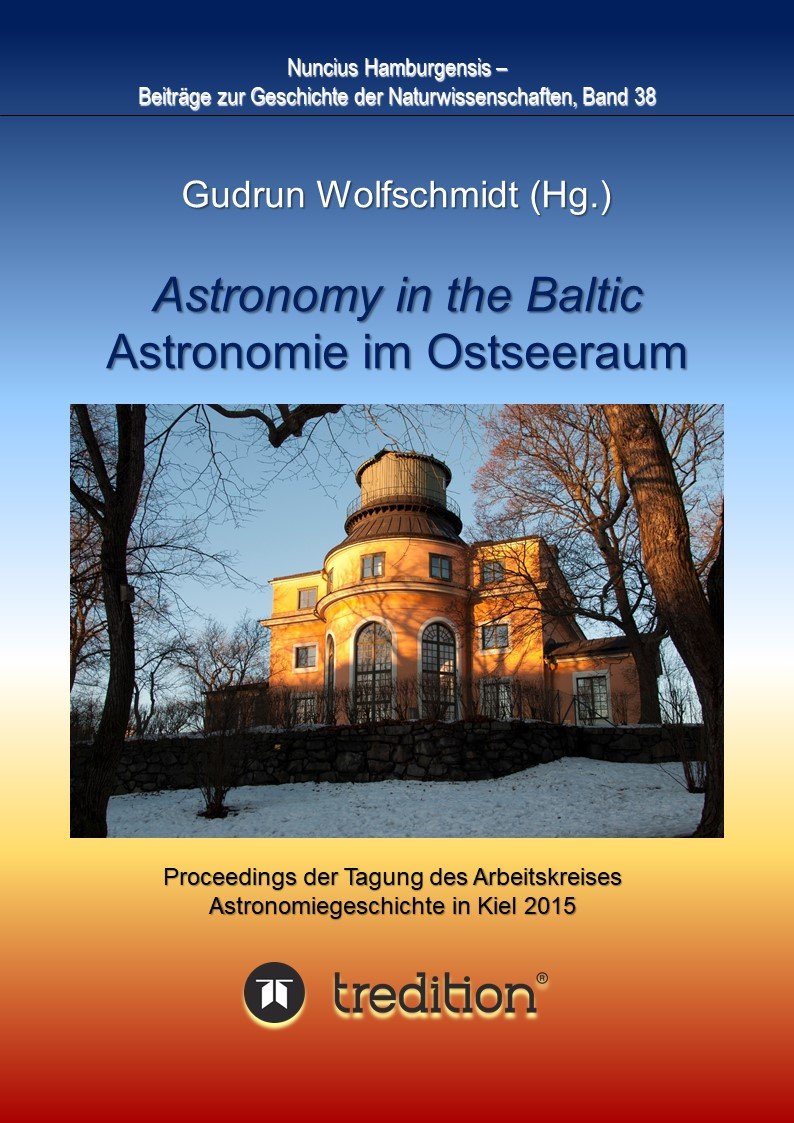

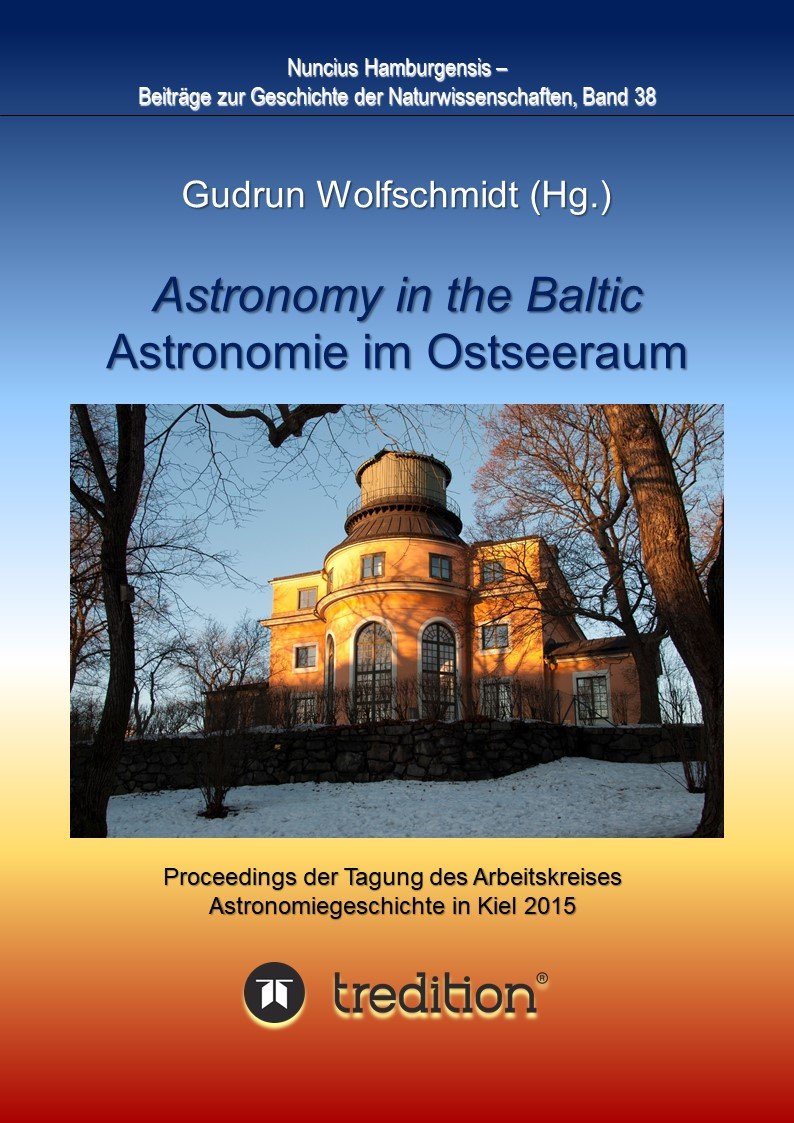

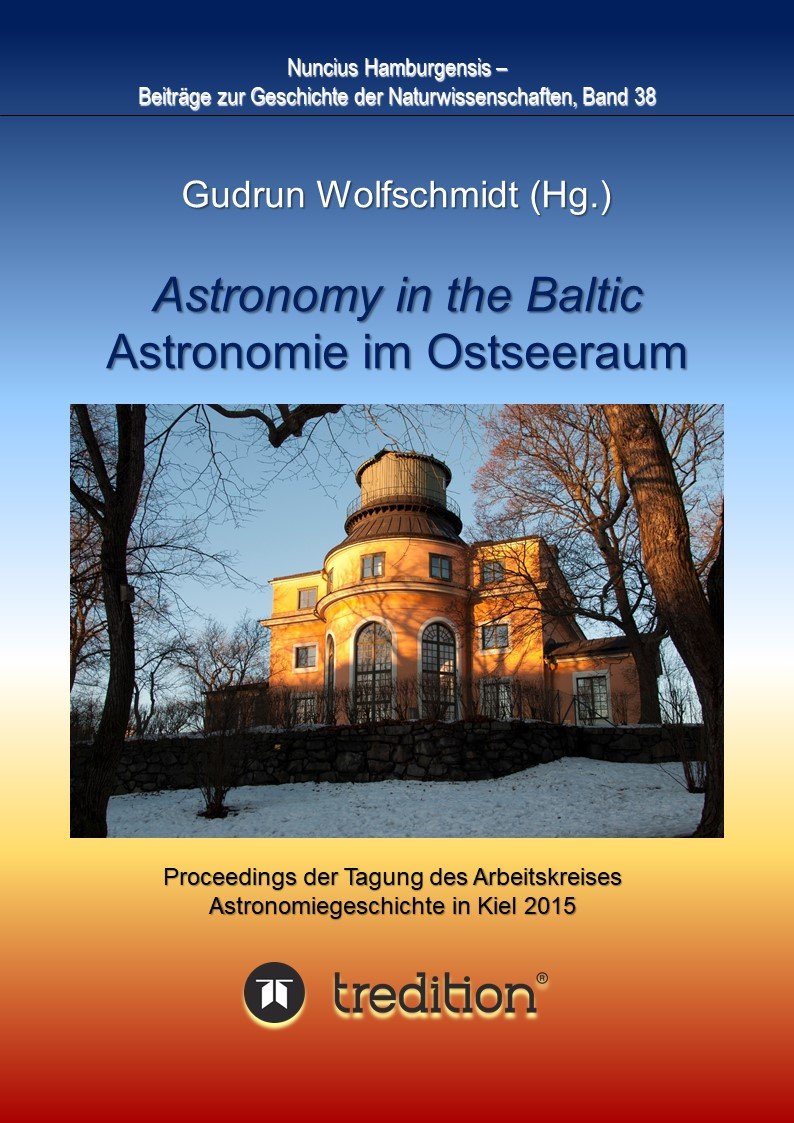

Fig. 1a. Stockholm Observatory, built by Carl Hårleman, 1748-1753 (Wikipedia, CC3, I99pema, 2003)

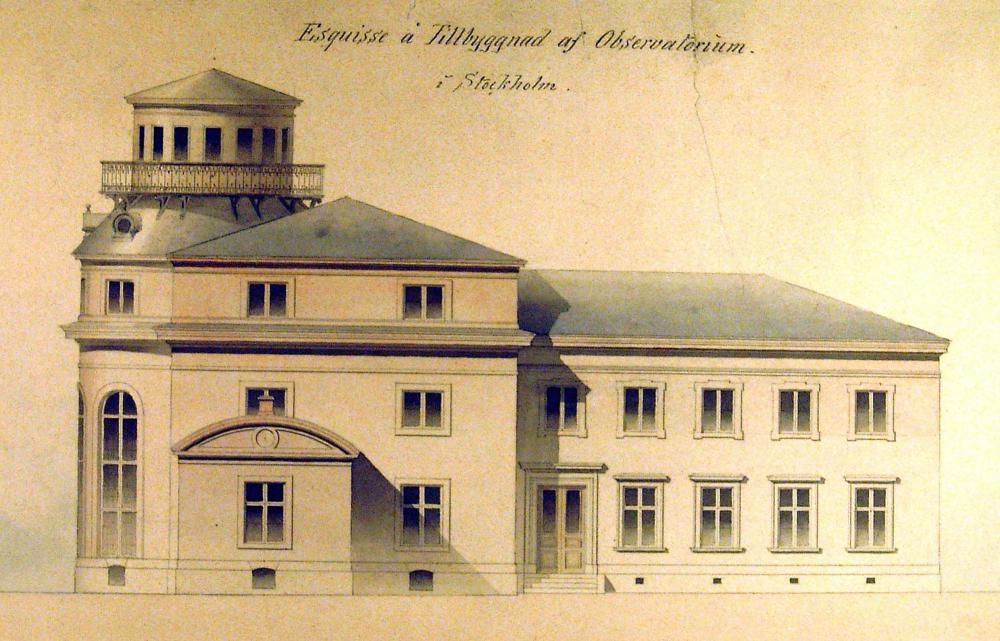

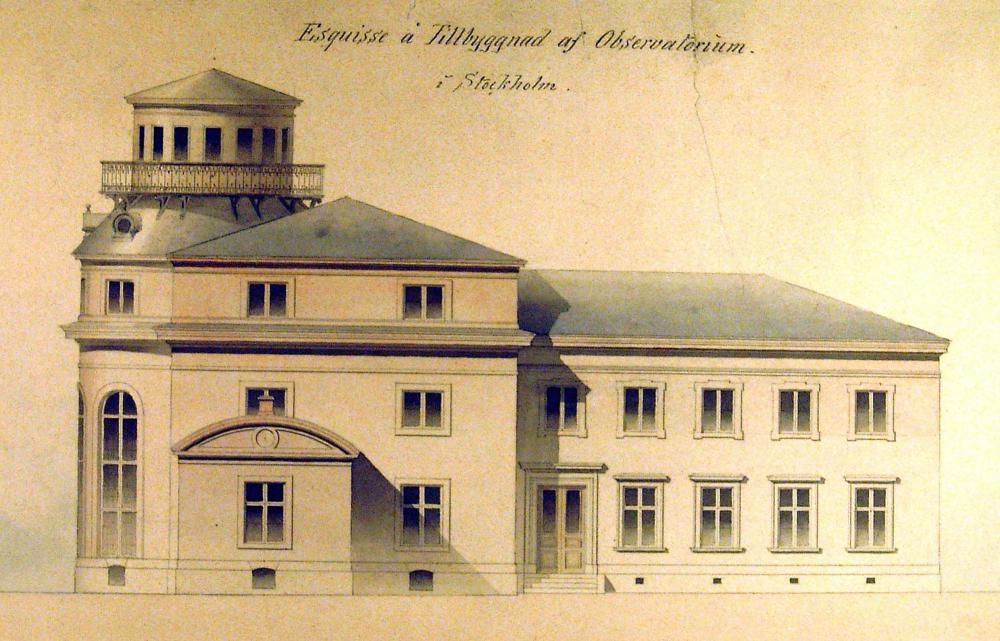

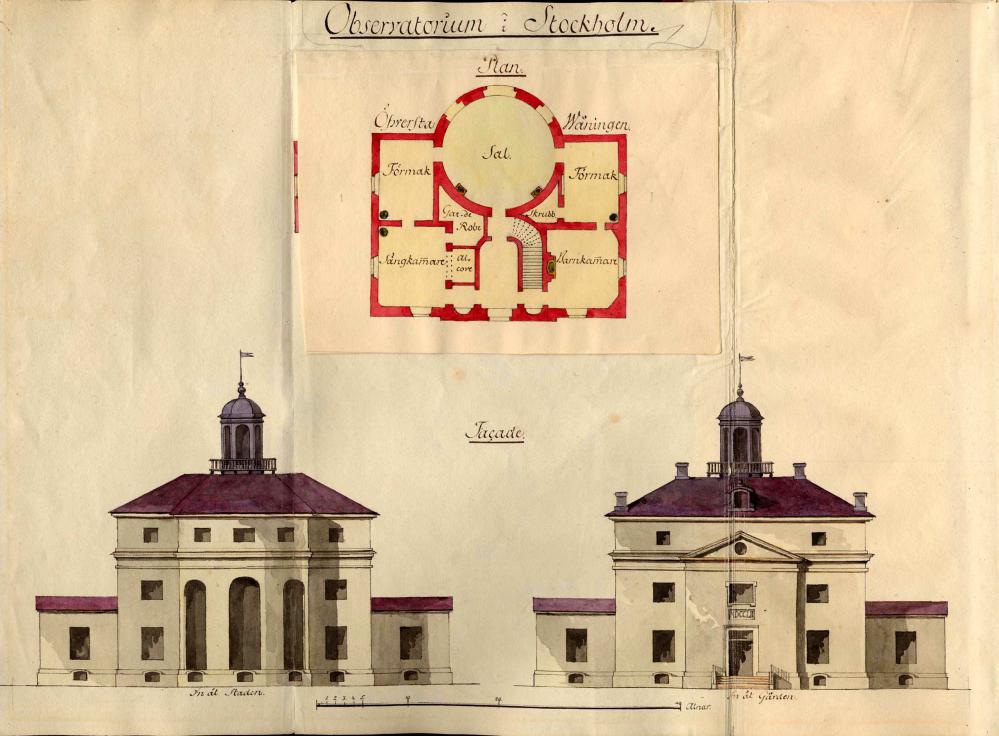

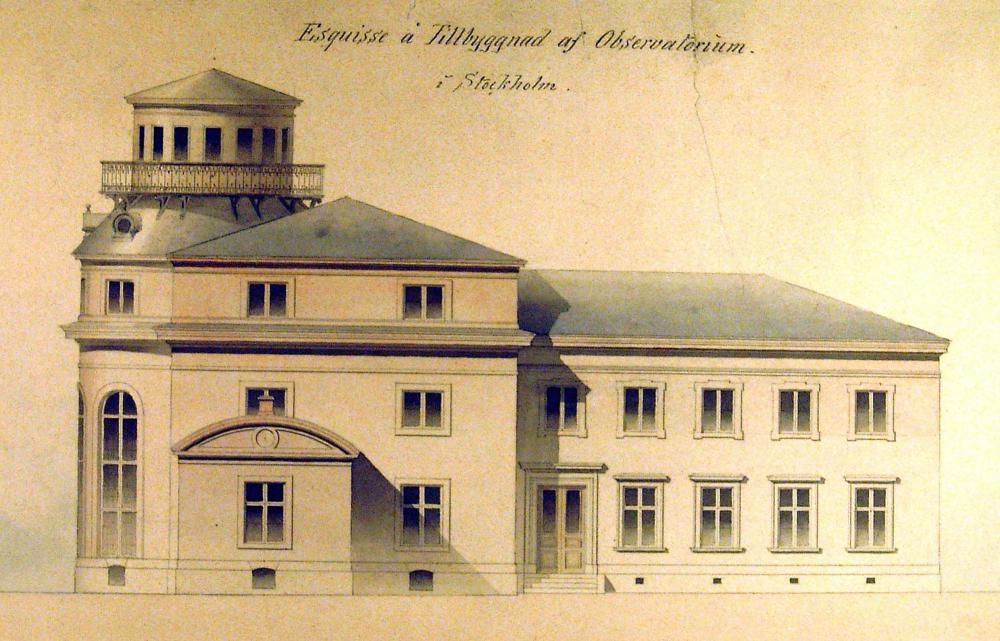

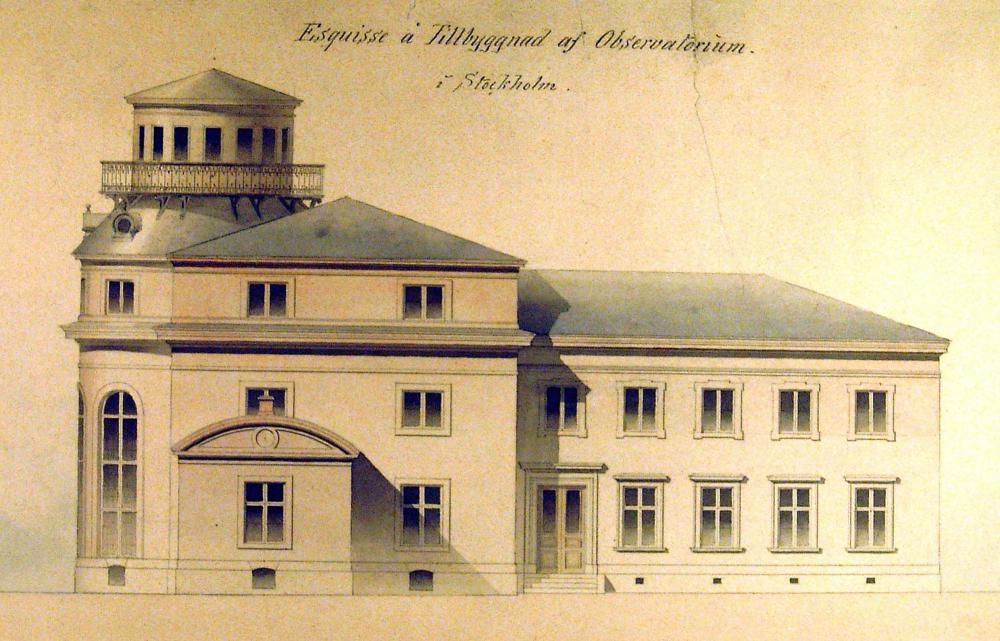

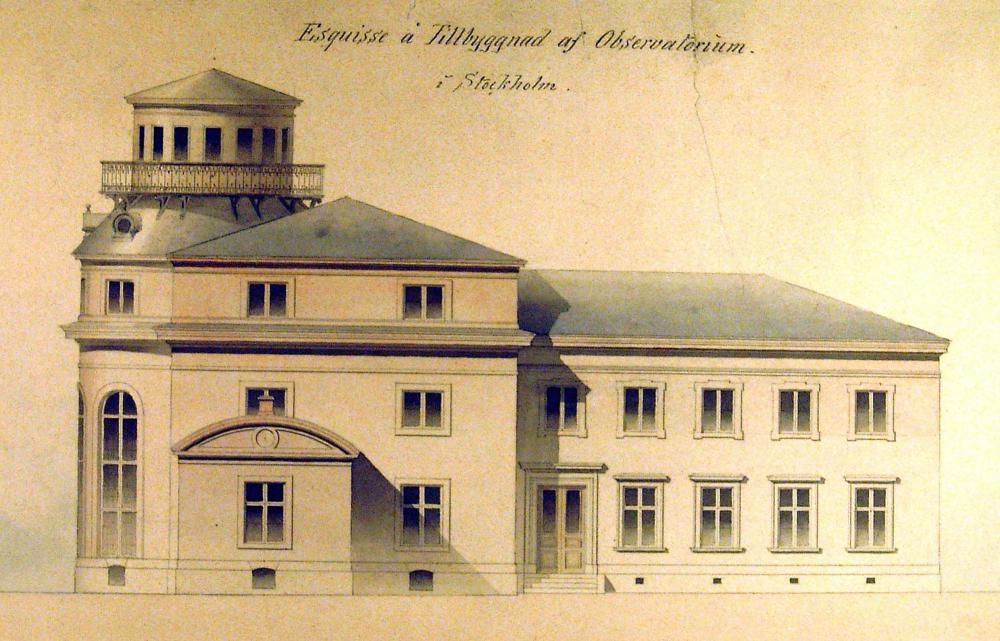

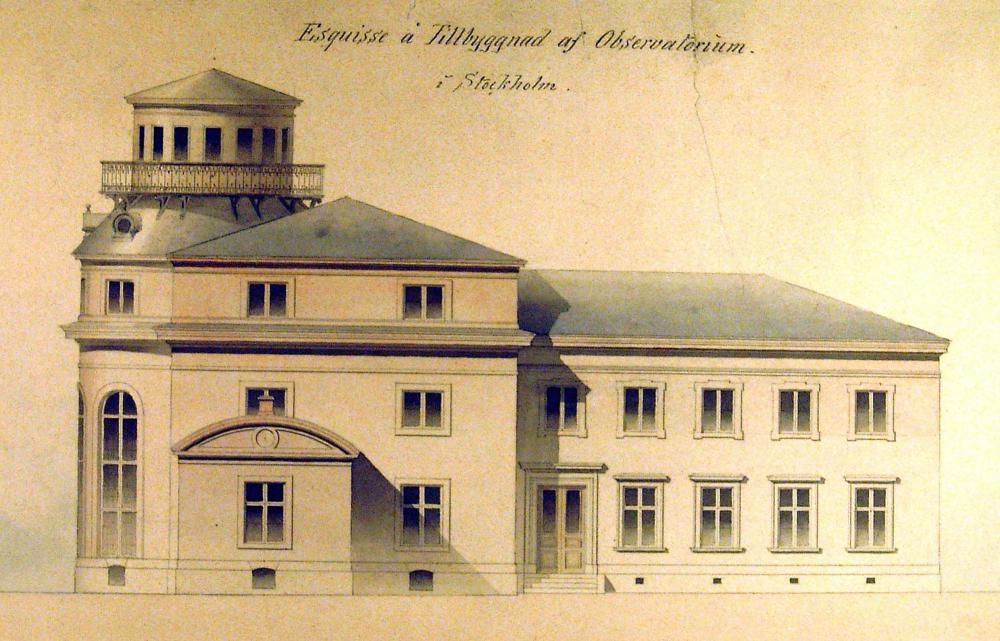

Fig. 1b. Stockholm Observatory with a small turret, drawing by Olof Tempelman in 1797 (Center for History of Science at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences)

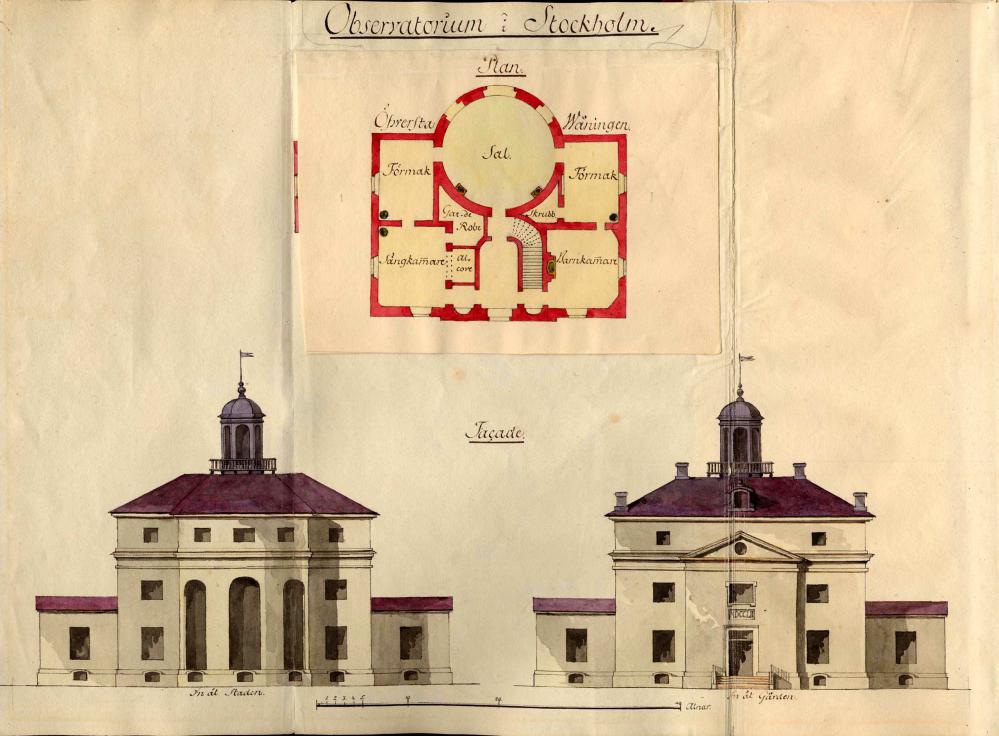

The Stockholm Observatory, the second oldest observatory in Sweden after the Celsiushuset in Uppsala (1741), was founded in 1748, built by Carl Hårleman (1700--1753) in Swedish rococo style, and inaugurated in 1753. Due to the high central body, the observatory building gets its character. The building’s circular room shape is marked in the bulge of the façade.

Hårleman had already designed the old Uppsala Observatory. Pehr Elvius the younger (1710--1749), a student of Anders Celsius (1701--1744) at Uppsala, was astronomer, founding member and secretary general to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (1739), had promoted the idea of a Stockholm Observatory.

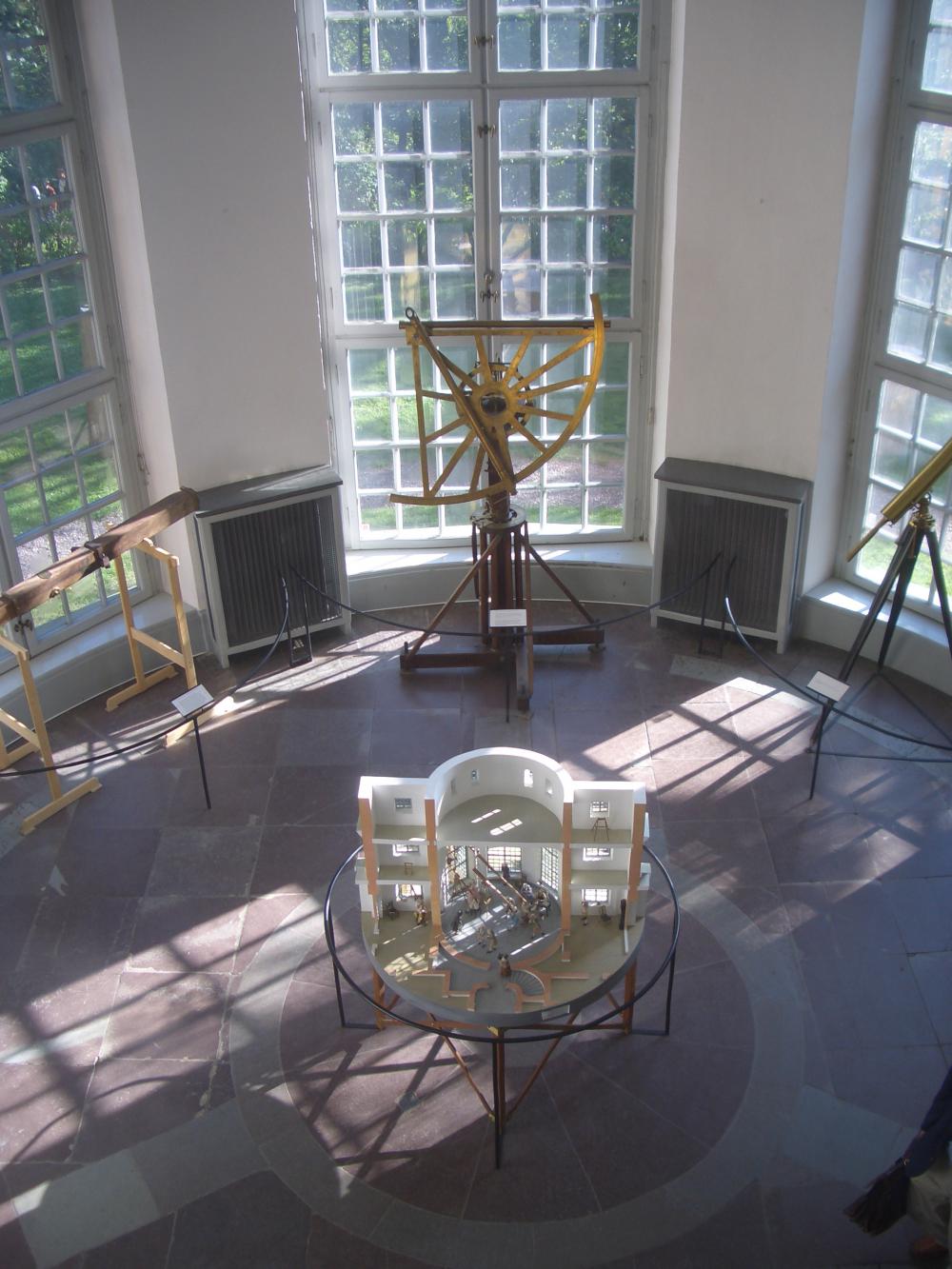

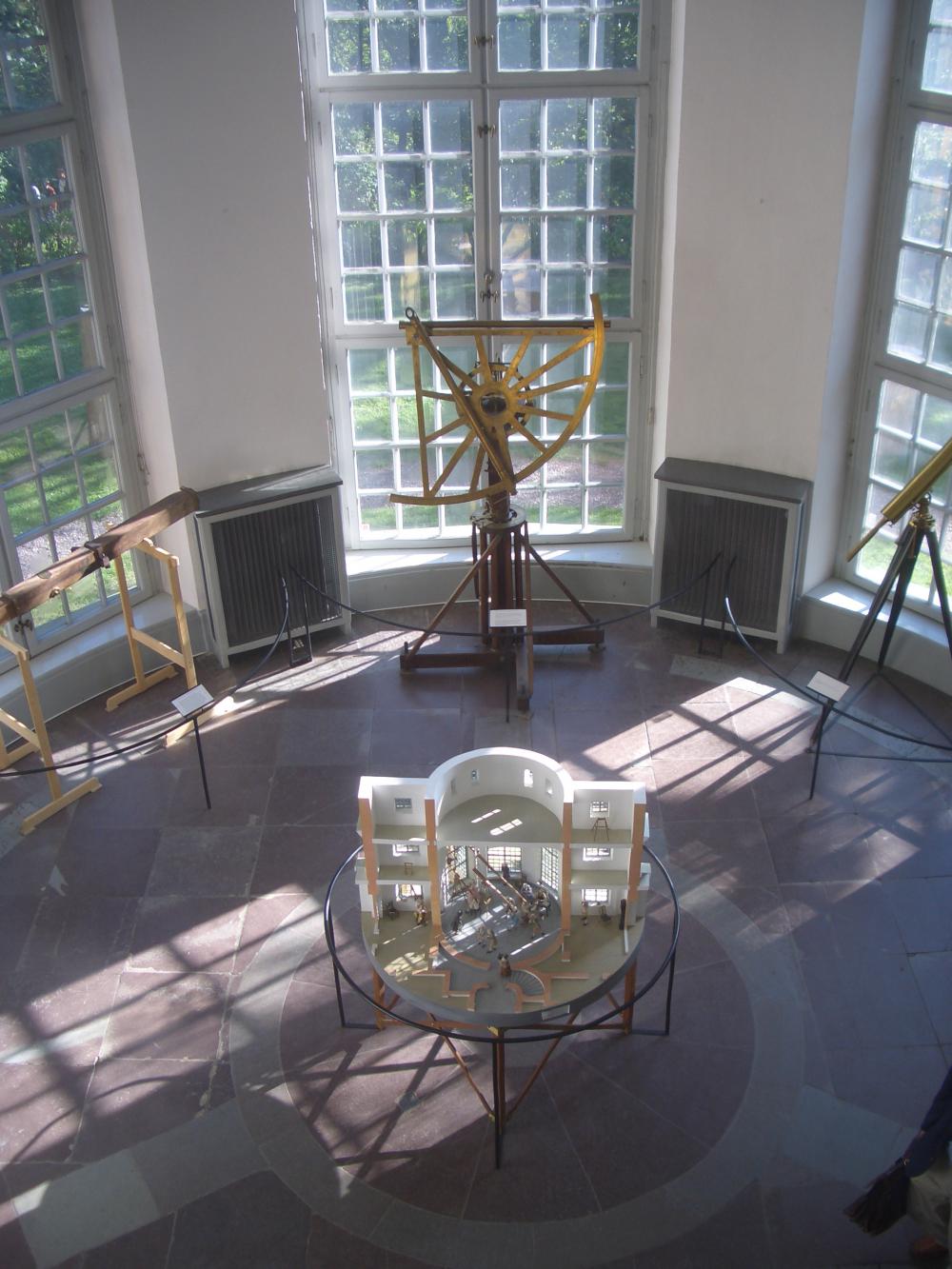

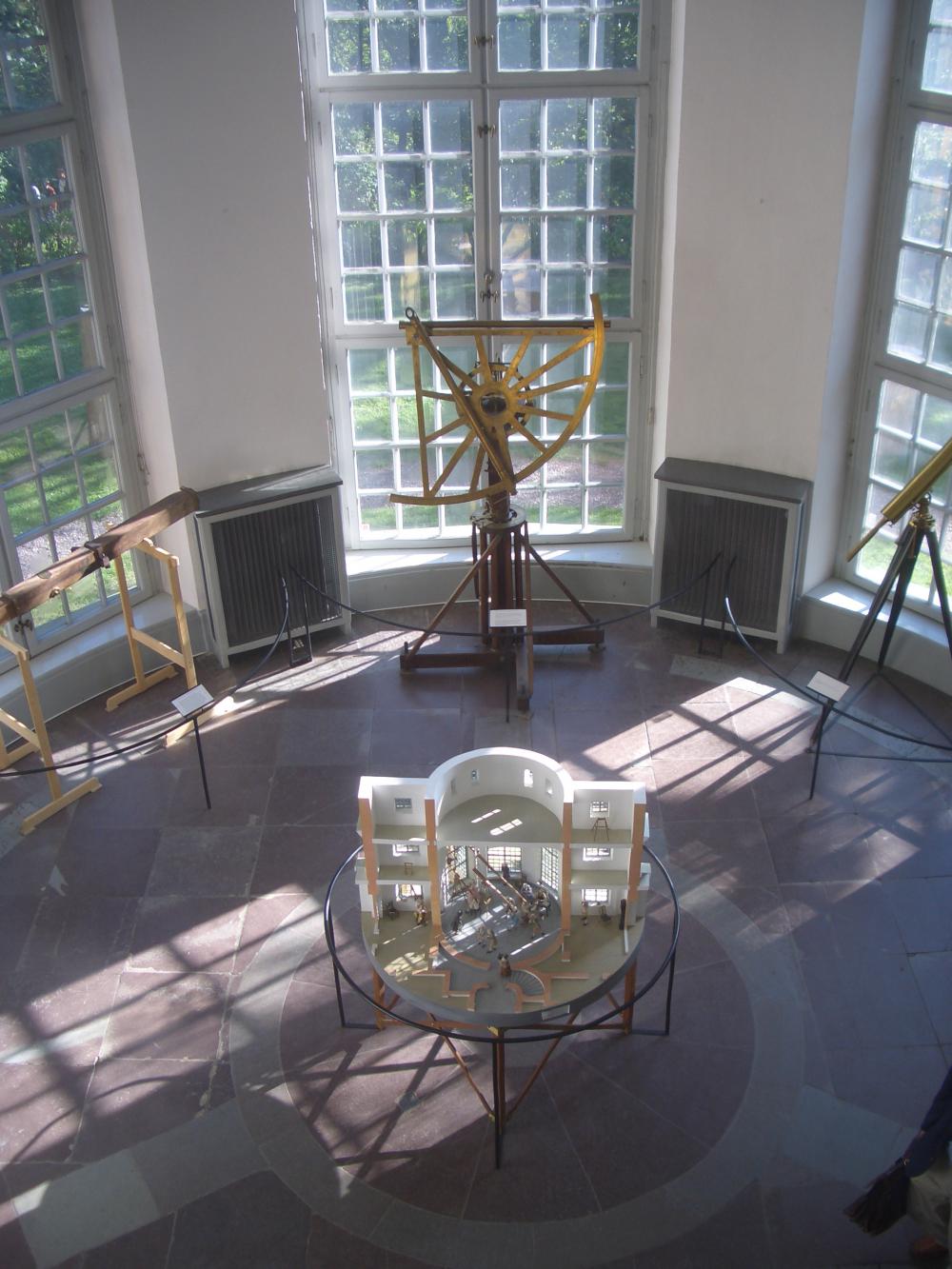

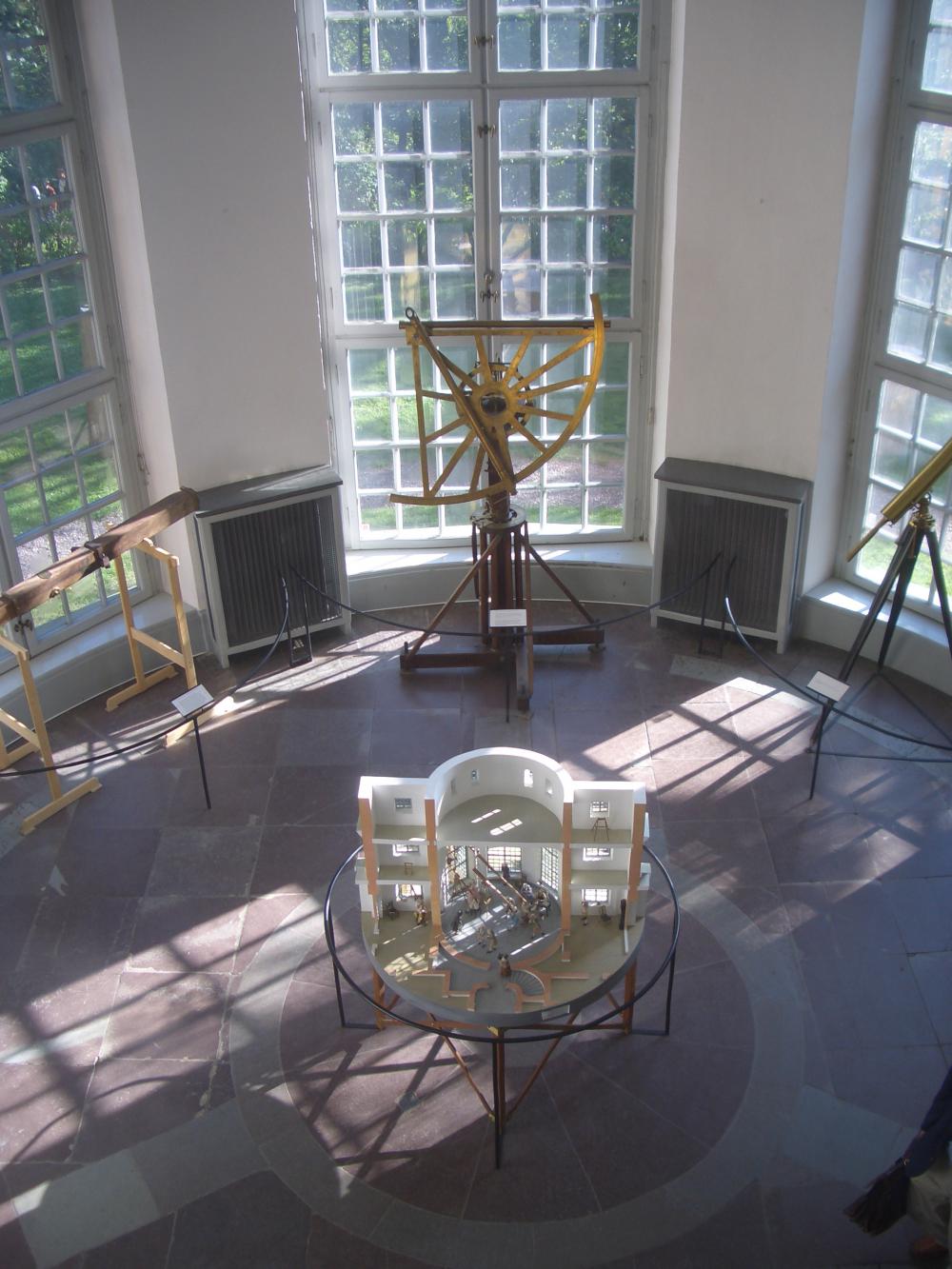

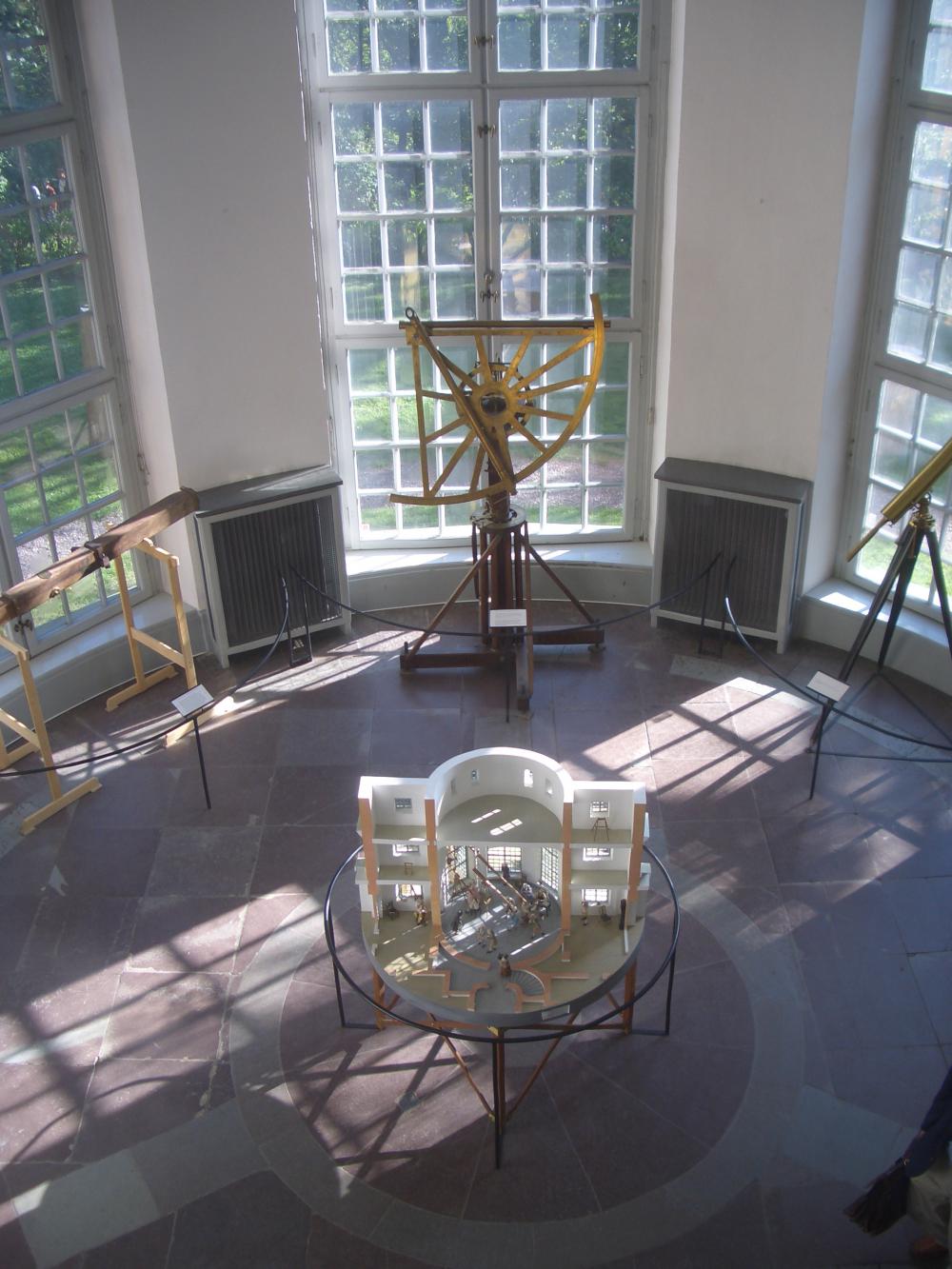

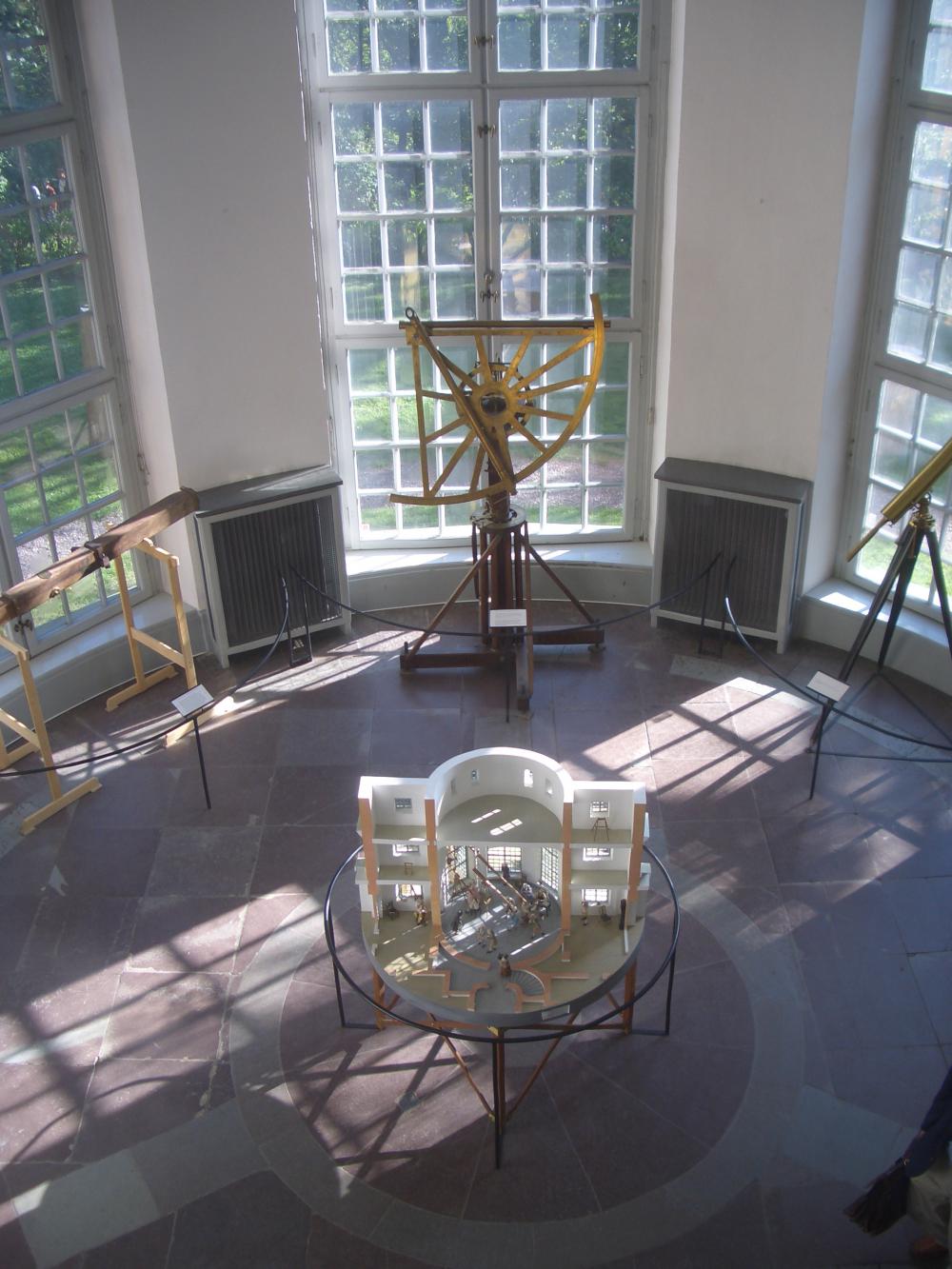

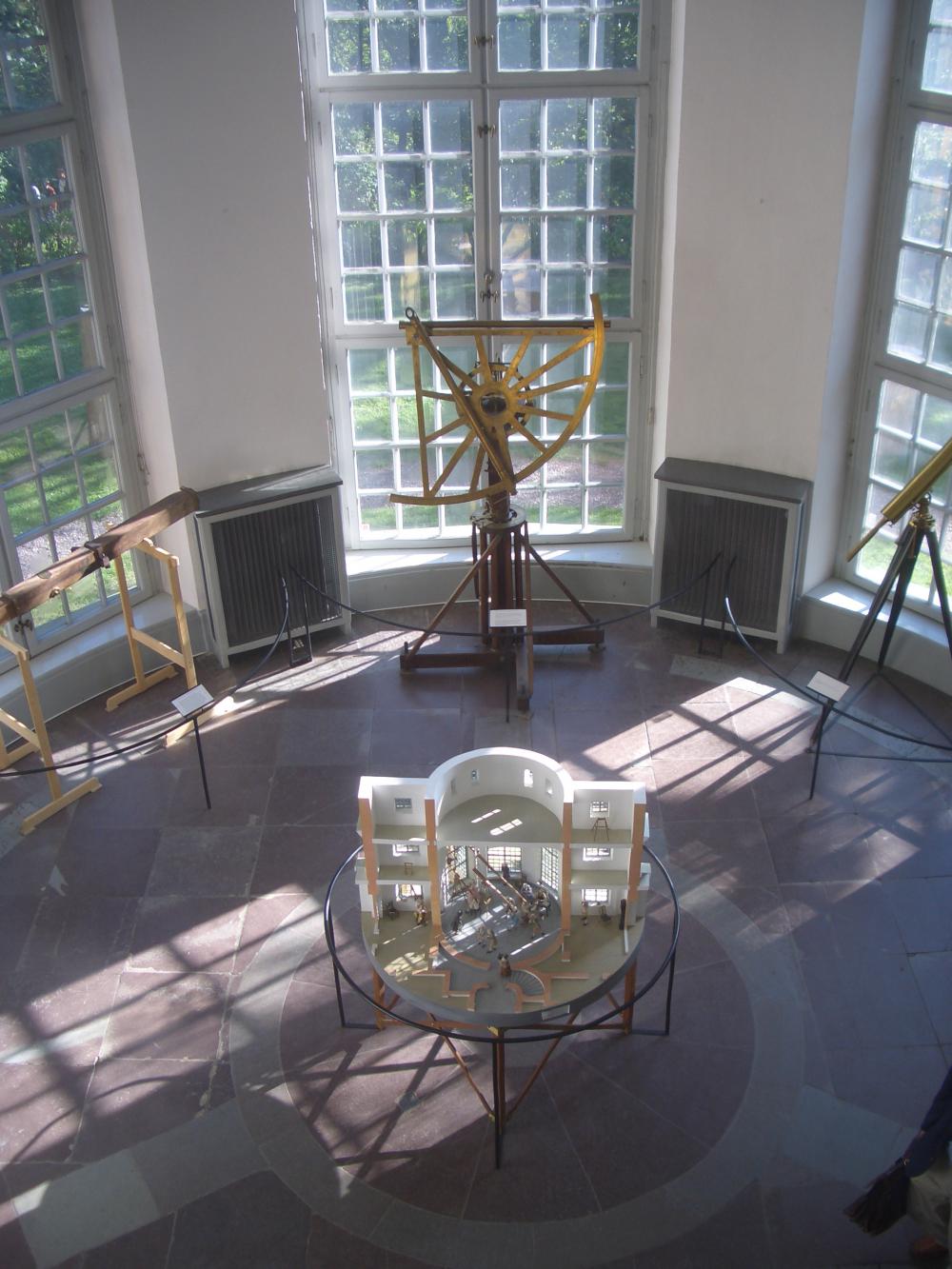

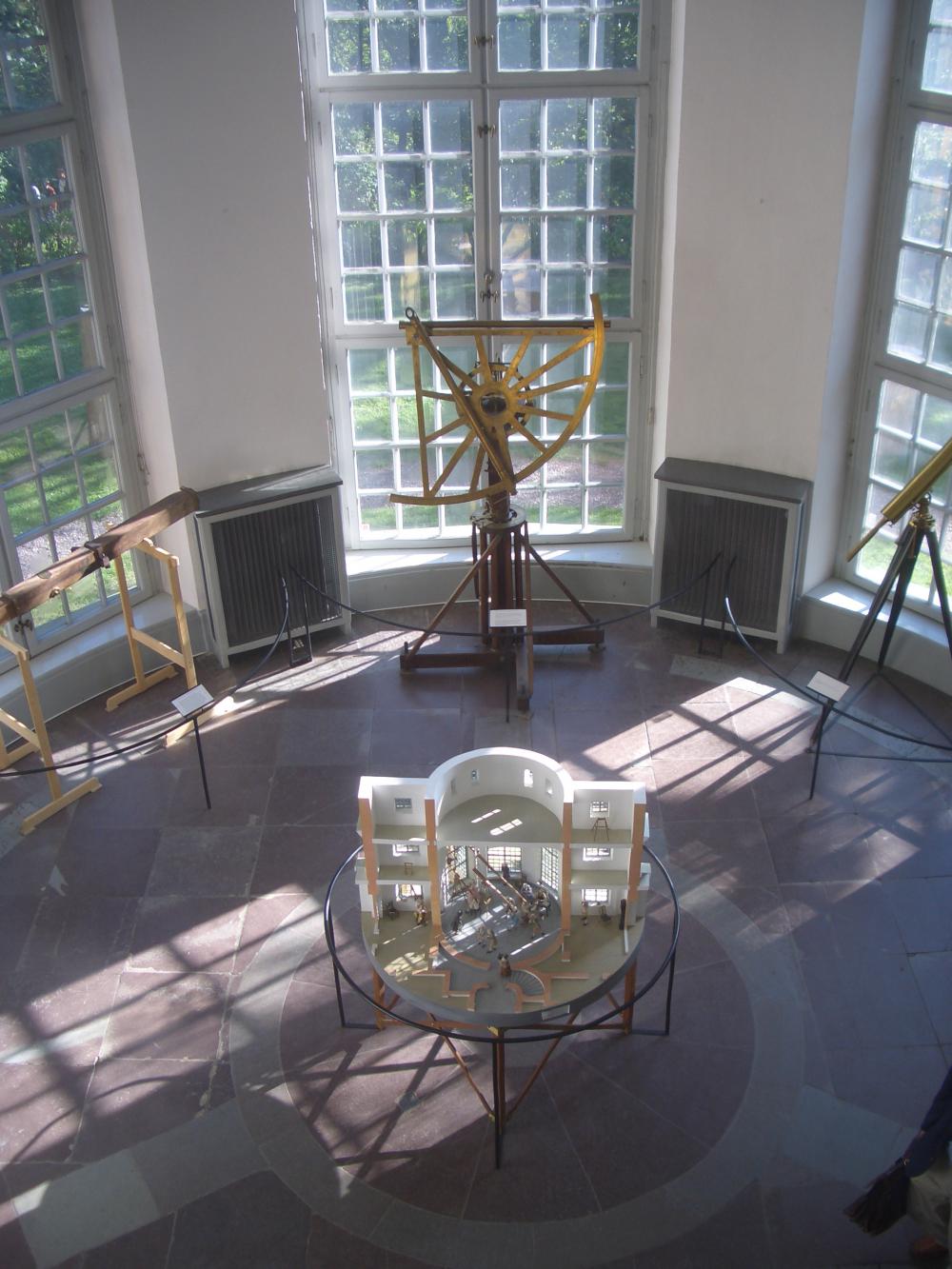

Fig. 2. Stockholm old Observatory, round central room with 18th century instruments (Photo: Helen Pohl)

The design of the Stockholm old observatory is not a tower observatory, but a building with a main room for observations in the ground floor, this round central room was oriented towards the south. Exhibited are now (cf. Fig. 2) from the left a John Dollond achromatic refractor, which belonged to Samuel Klingenstierna (1698--1765), and was bought in 1760, a quadrant by John Bird from 1757, and a Gregorian reflector by William Cary, ca. 1800.

The long tradition in astrometry of Stockholm’s old observatory is shown in the a marble inlaid meridian line. It has previously served as the national zero meridian for Sweden, the position was 35°43’19.5’’ E Ferro, the international zero meridian of that time.

The Meridian Room was in the room farthest to the east, here Stockholm’s local time was determined. In the 1820s, when the premises were redistributed, these observations were moved to an adjoining room with a newly acquired telescope. These daily observations to determine local time and also Swedish time lasted until 1900, when they switched to GMT (Greenwich Mean Time); then the Swedish time had to be changed by 14 seconds.

In the ground floor were besides the observing rooms, the library, the offices for the astronomers, and a cabinet of naturalia, in the cellar, the workshop for instrument making. In the second and third floor were the appartments for the astronomers.

The first director was Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin (1717--1783), who became after his magister in philosophy in 1743 a docent in astronomy in 1746, and an adjunct in 1748. Then he served since 1749 for a long time as secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. His interest was observing the moons of Jupiter; the publication appeared: Specimen astronomicum, de satellitibus Jovis (Uppsala 1741).

An especially important activity of the Swedish astronomers were the transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769 with international cooperation.

Fig. 3. Observing the Venustransit (1761), model in Stockholm Observatory (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

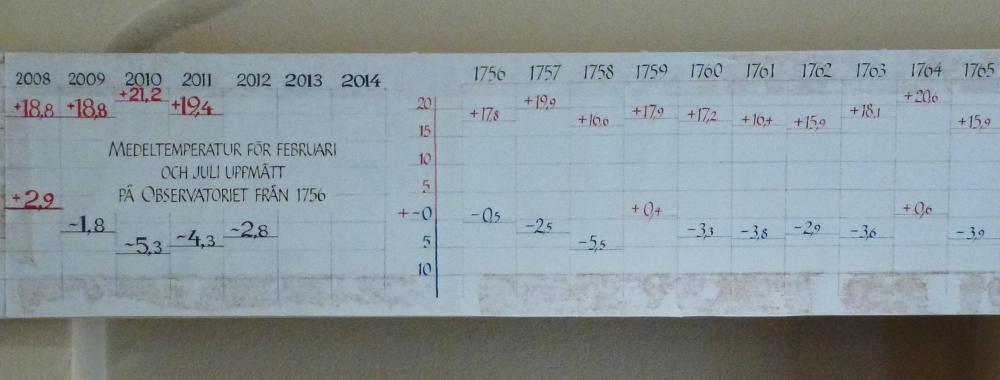

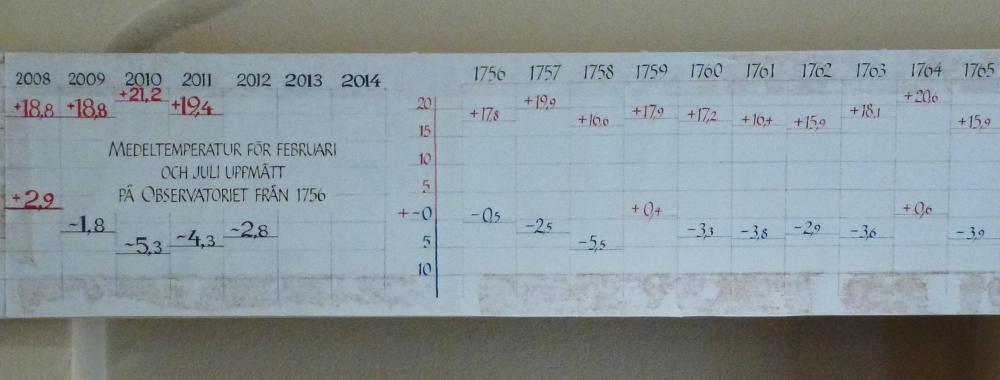

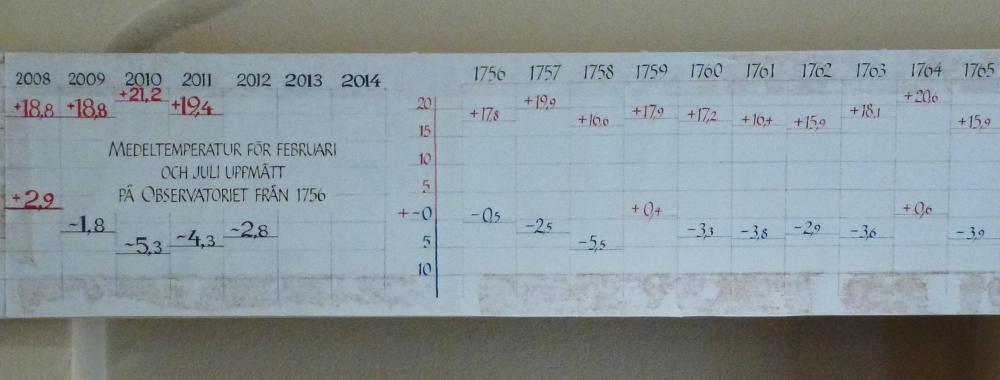

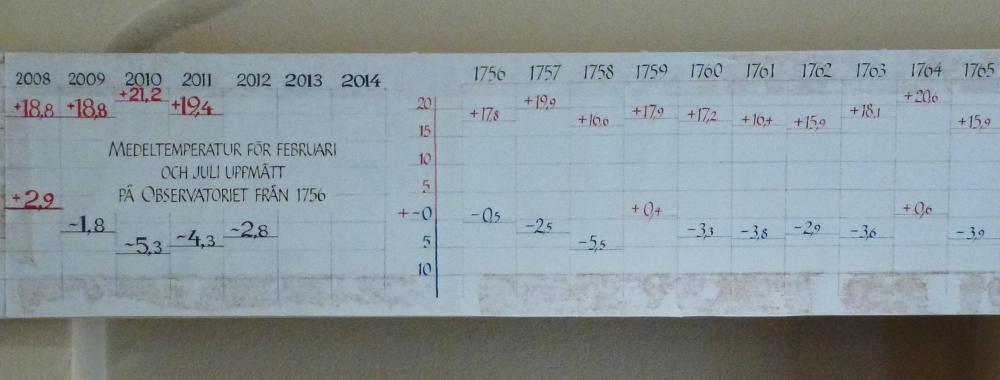

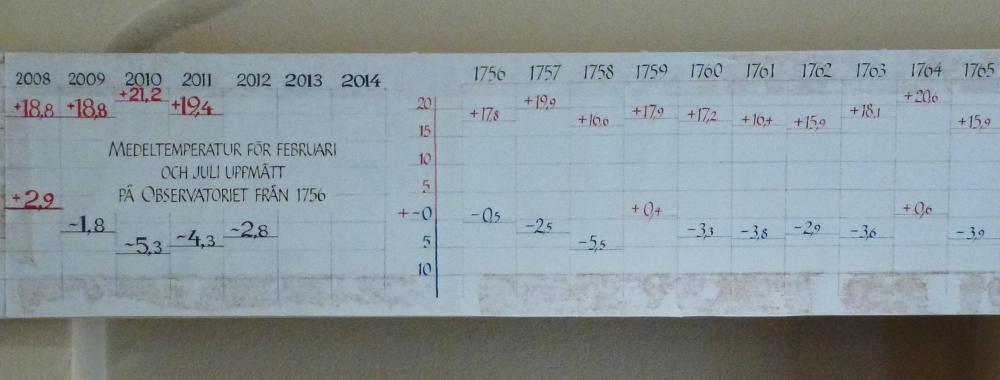

Remarkable research items are the records of daily weather observations from the observatory going back to 1756. In the Weather Chamber there is a temperature loop that shows the average temperature during the warmest (July) and coldest (February) month of the year from the 18th century, since Wargentin’s time, until today. Three times a day, temperature and rainfall have been measured at the observatory since 1756, and this is therefore the only place in the world, where the weather has been observed continuously for more than 250 years (air temperature, air pressure, rainfall, cloud amounts, snow depth). Today, the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI) is responsible for the measurements which are important for climate studies due to its long-term sustainable observational standards and high-quality time series data.

Fig. 3. Weather observations of Stockholm Observatory: The temperature loop begins 1756 and continues until today (Wikipedia, CC3, Holger Ellgaard)

In 1838 a magnetic house was built and magnetic measurements were started. The Stockholm Observatory was enlarged: An extension and a new tower with dome were built in 1875 by architect Johan Erik Söderlund, and in 1881 additional wings were built.

In the 19th century astrophysics started in Stockholm. Famous directors were Hugo Gyldén (1841--1896) from Helsinki, director since 1871, specialist in celestial mechanics and early promoter of astrophotography the 1880s, and Bertil Lindblad (1895--1965), director since 1927, who studied the theory of the rotation of galaxies. Due to the growing city and the deteriorating conditions for observations, Lindblad had to organize the observatory’s move from the old building in the centre of Stockholm to a newly built Saltsjöbaden Observatory on Karlsbaderberget, which was opened in 1931, designed by the architect Axel Anderberg.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 7

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 19:12:56

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

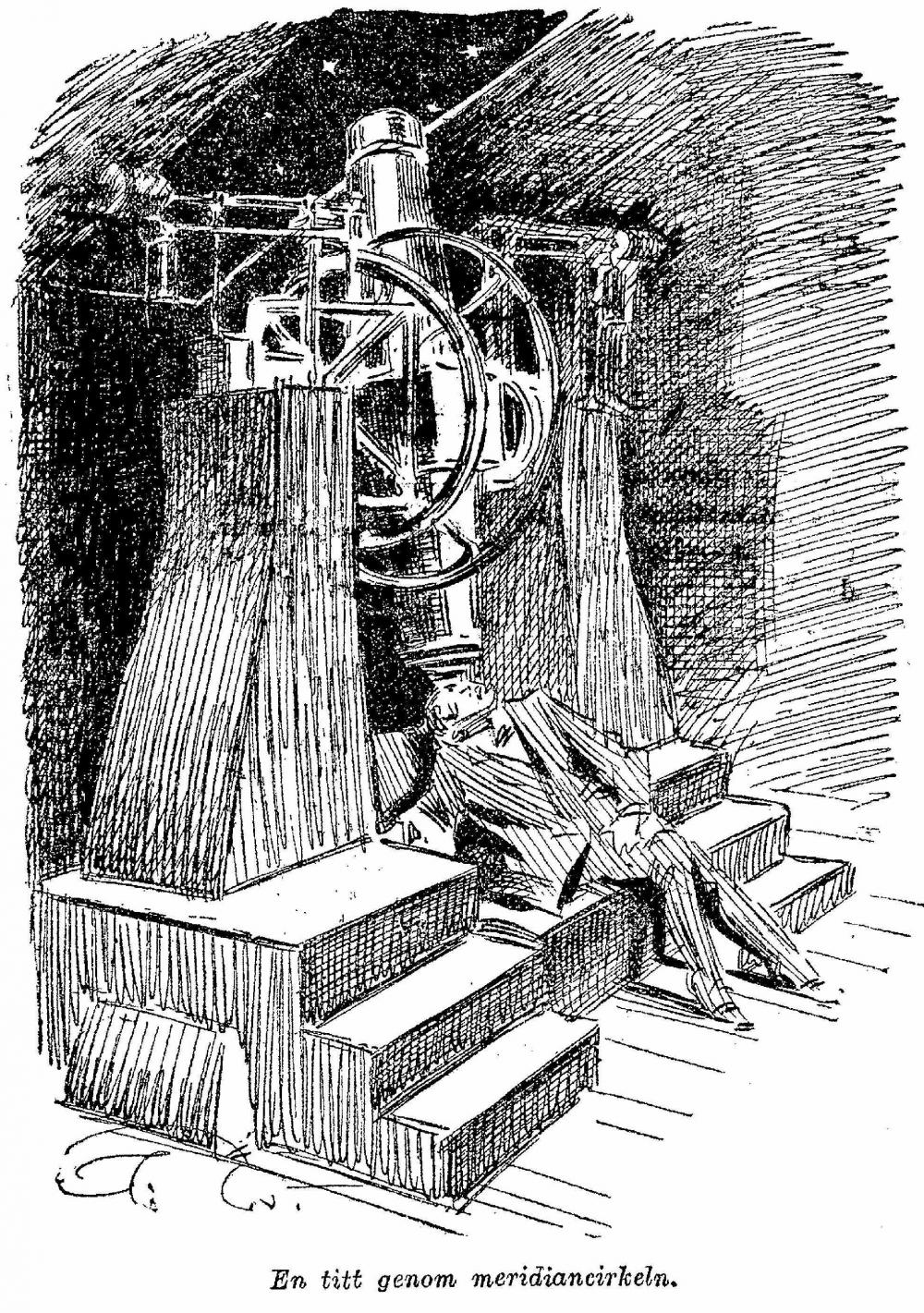

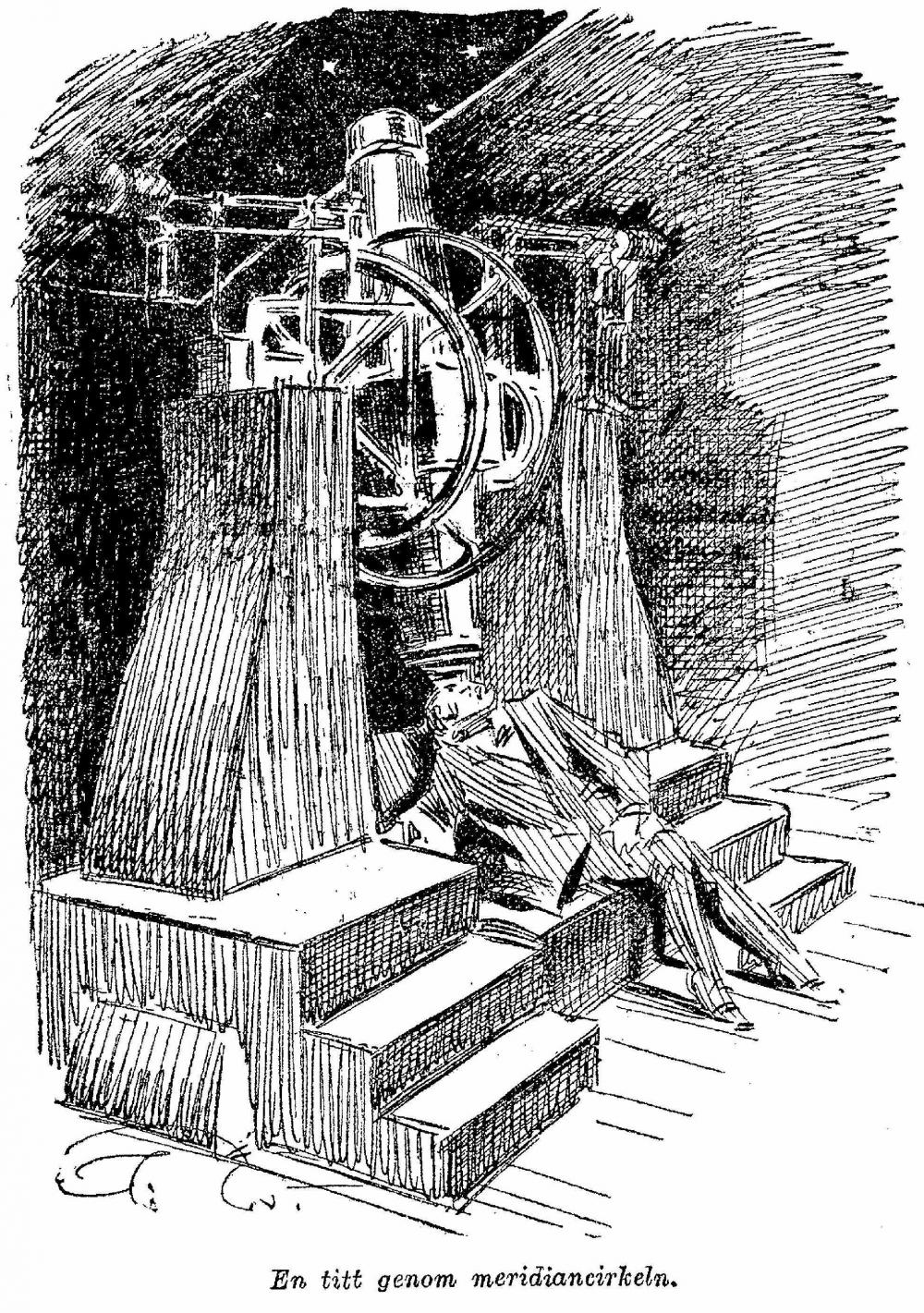

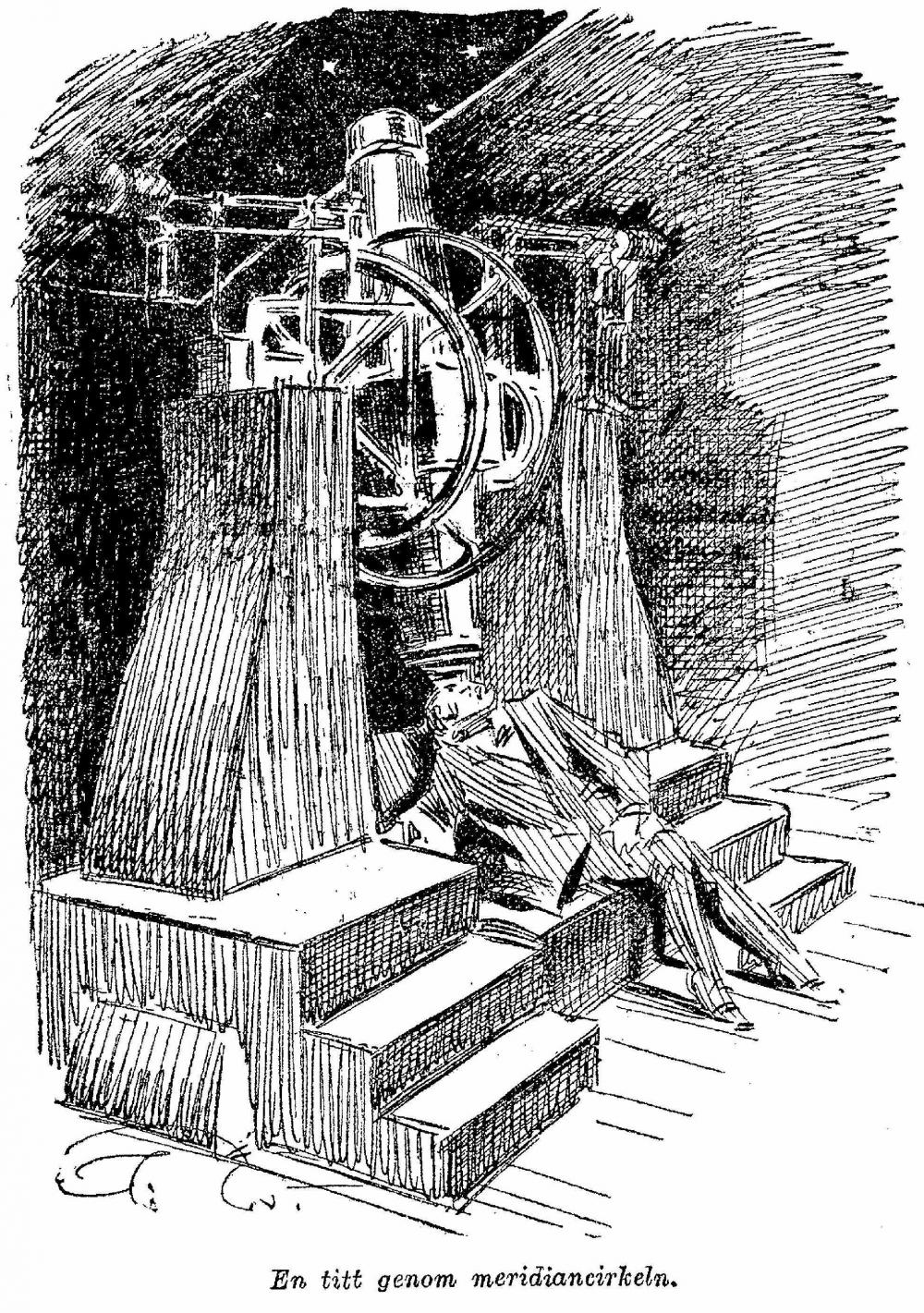

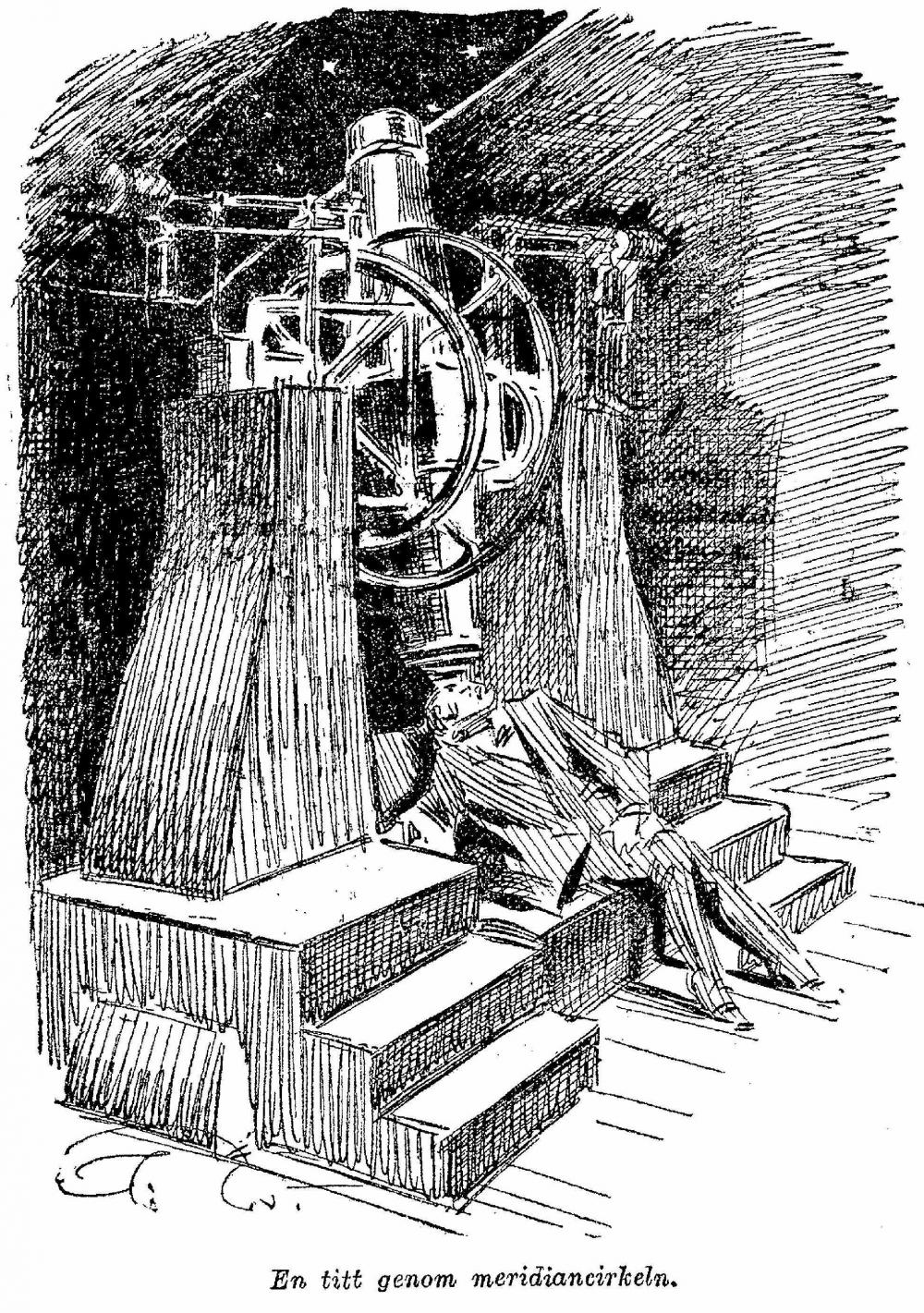

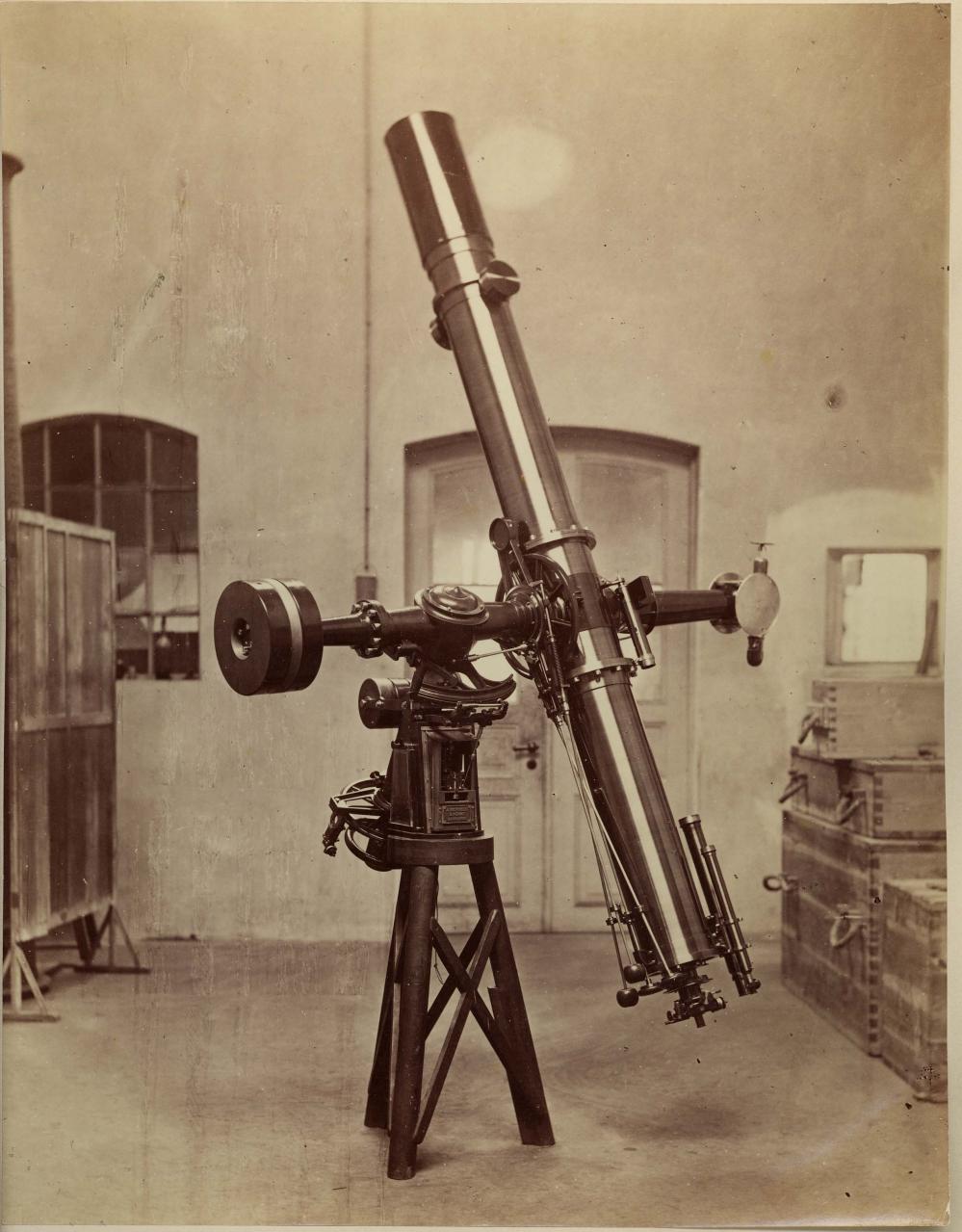

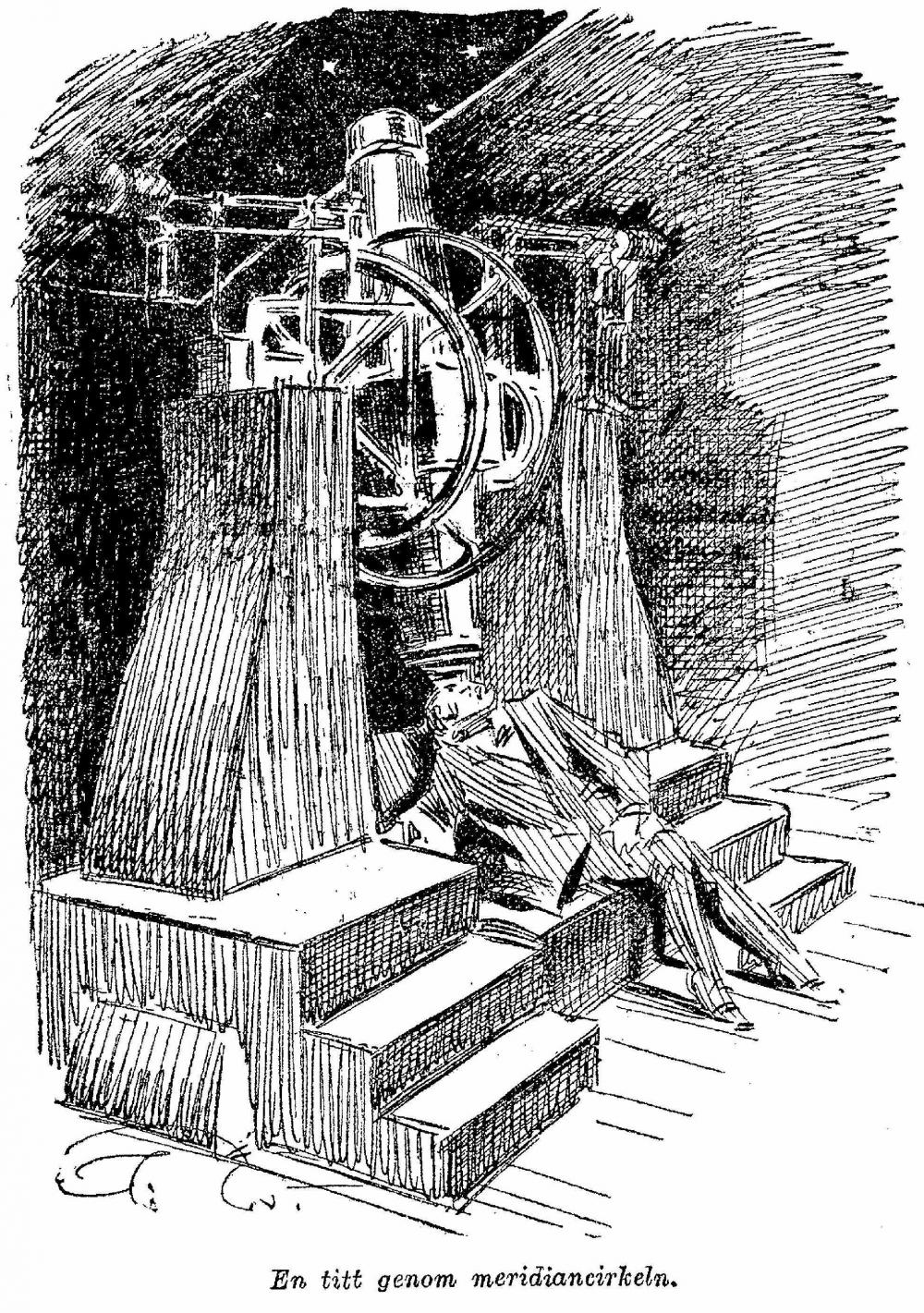

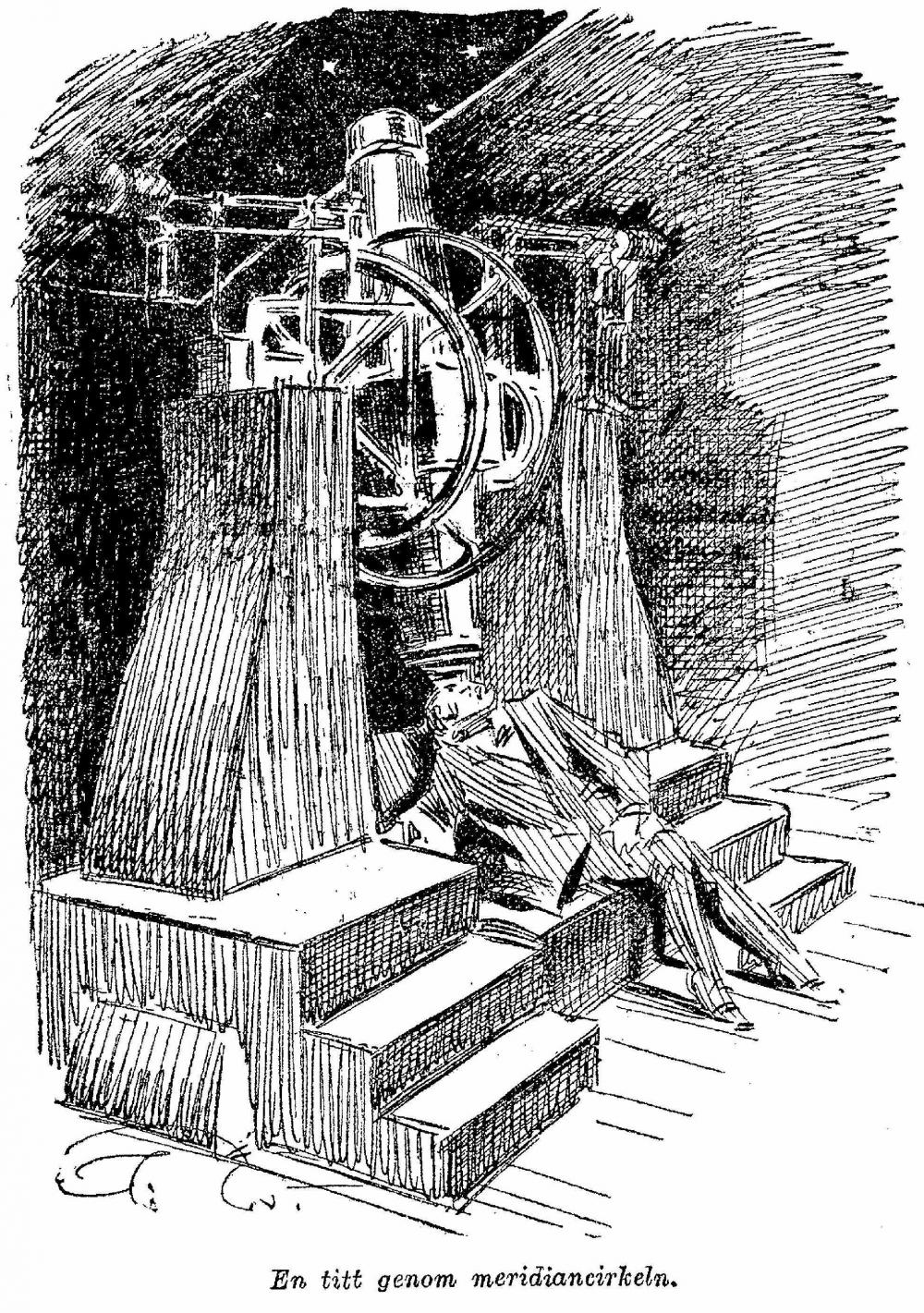

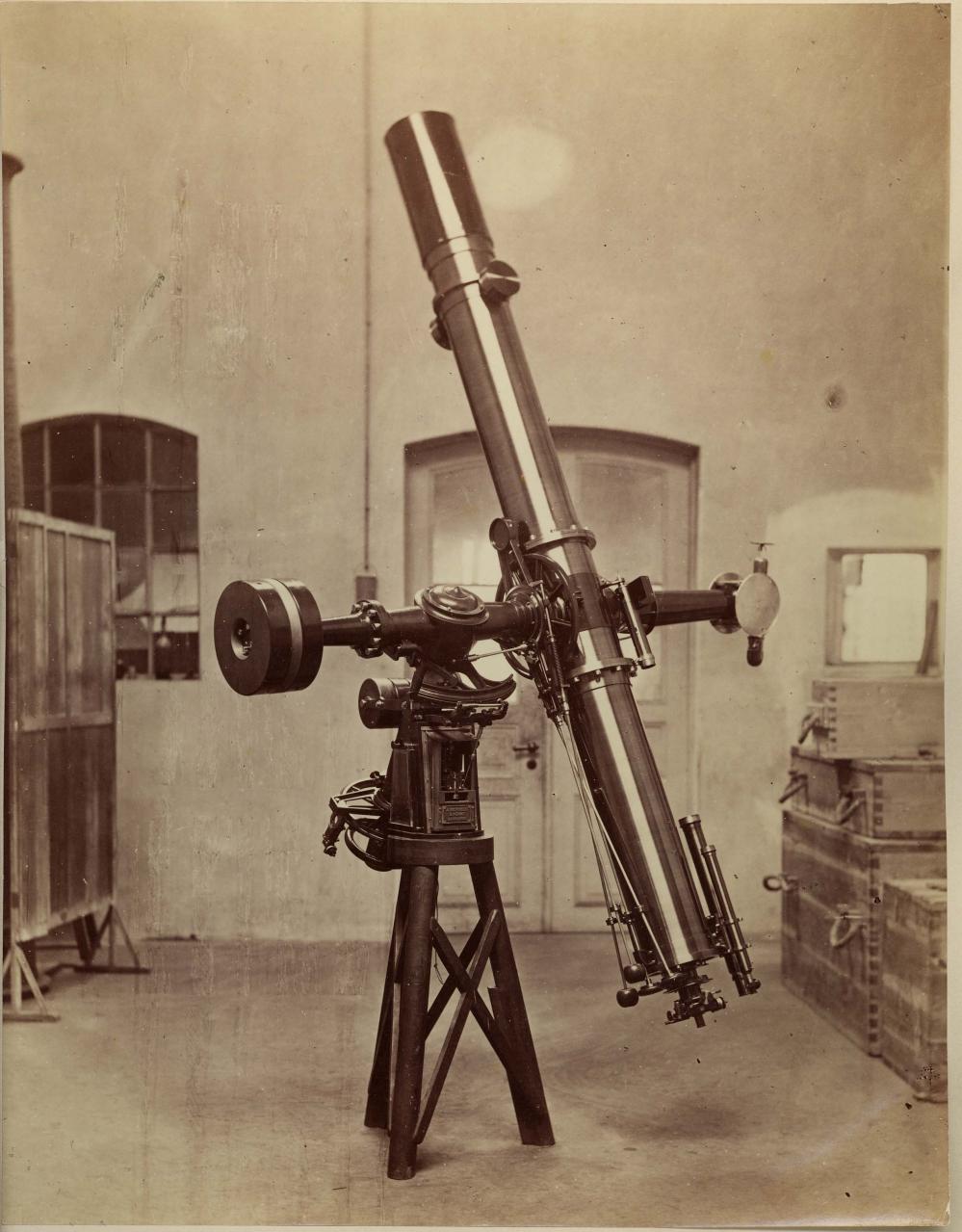

Fig. 4a. Meridian circle, Traugott Leberecht Ertel (1778--1858) of Munich (1830) (© Inga Elmqvist Söderlund, Academy of Sciences)

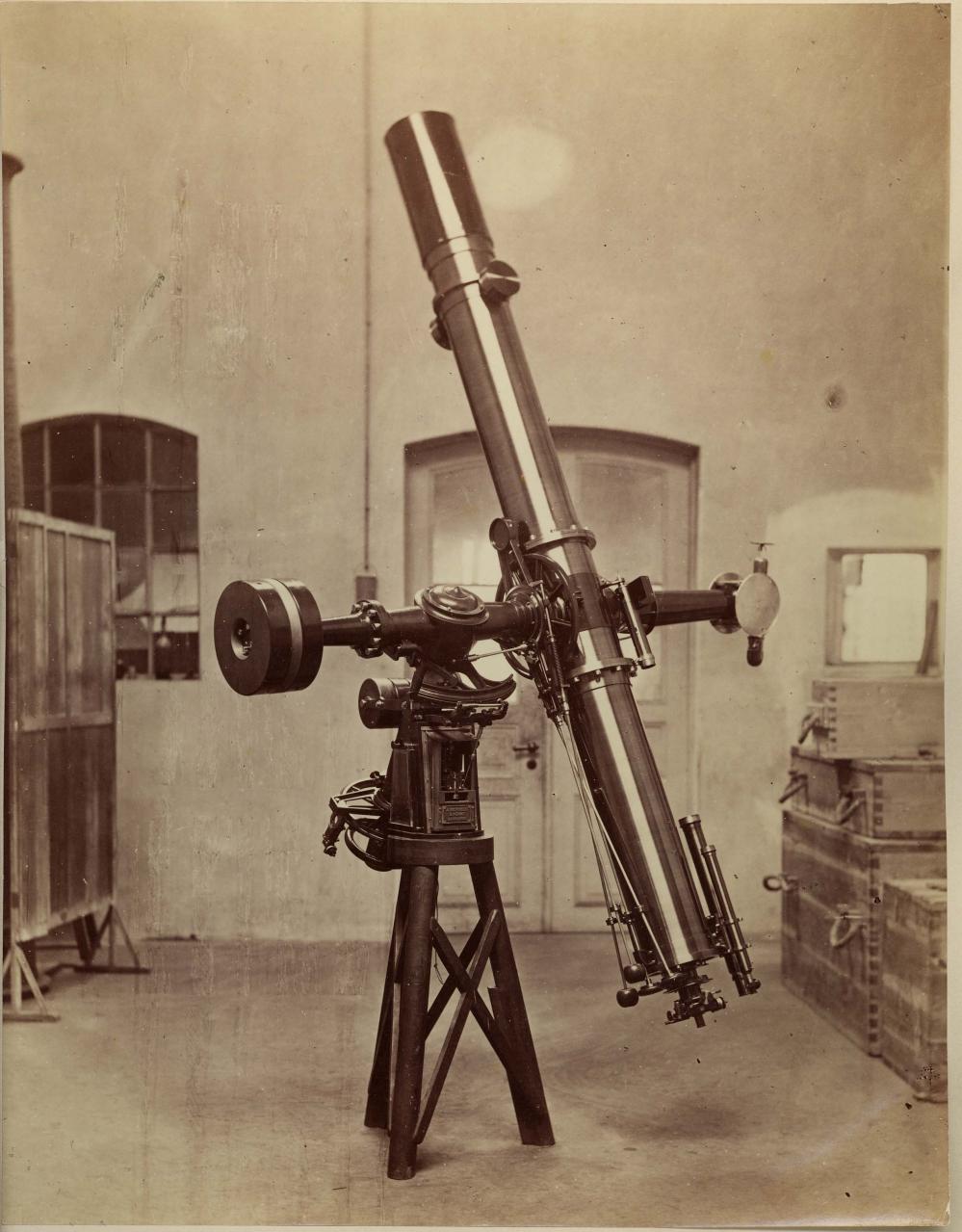

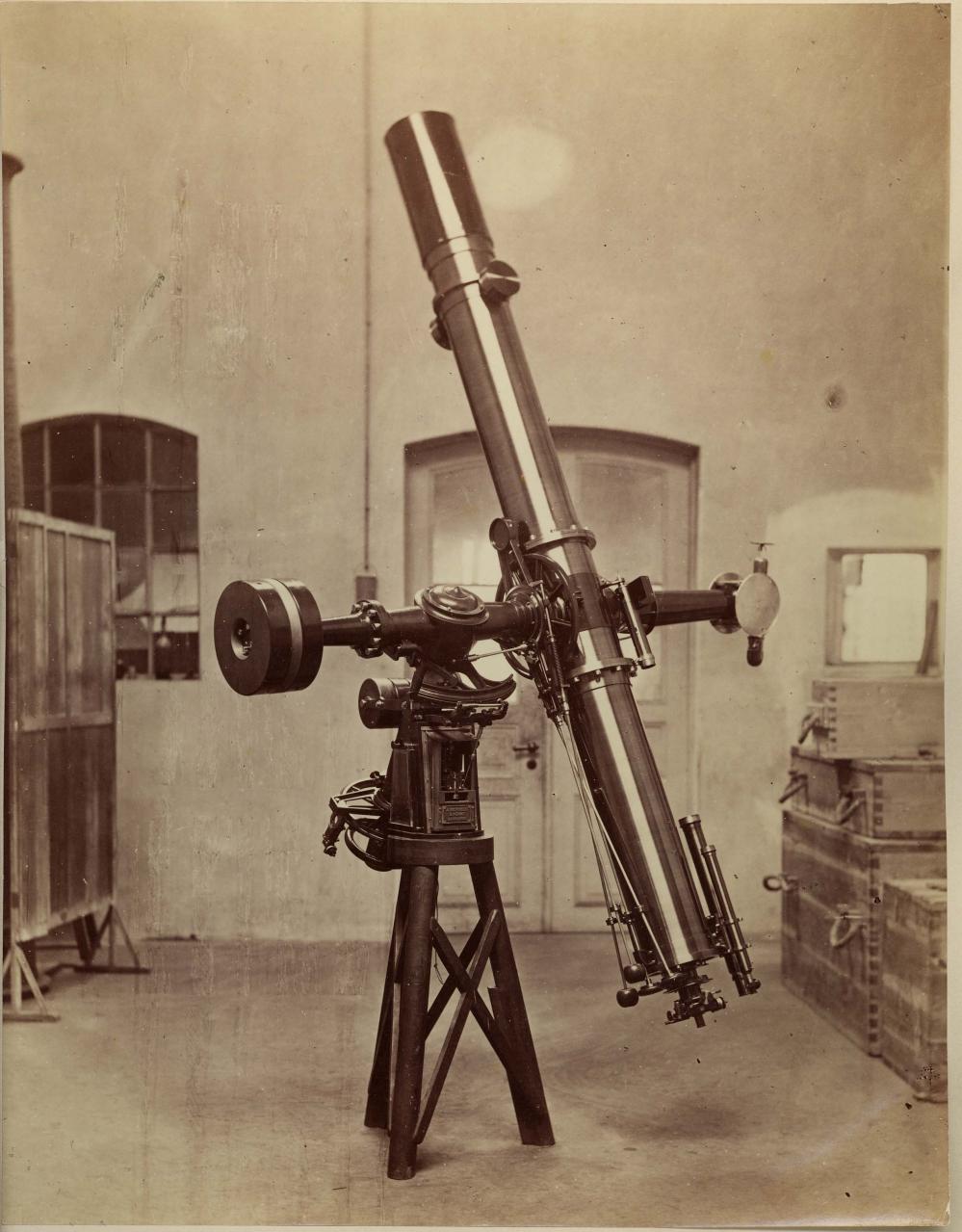

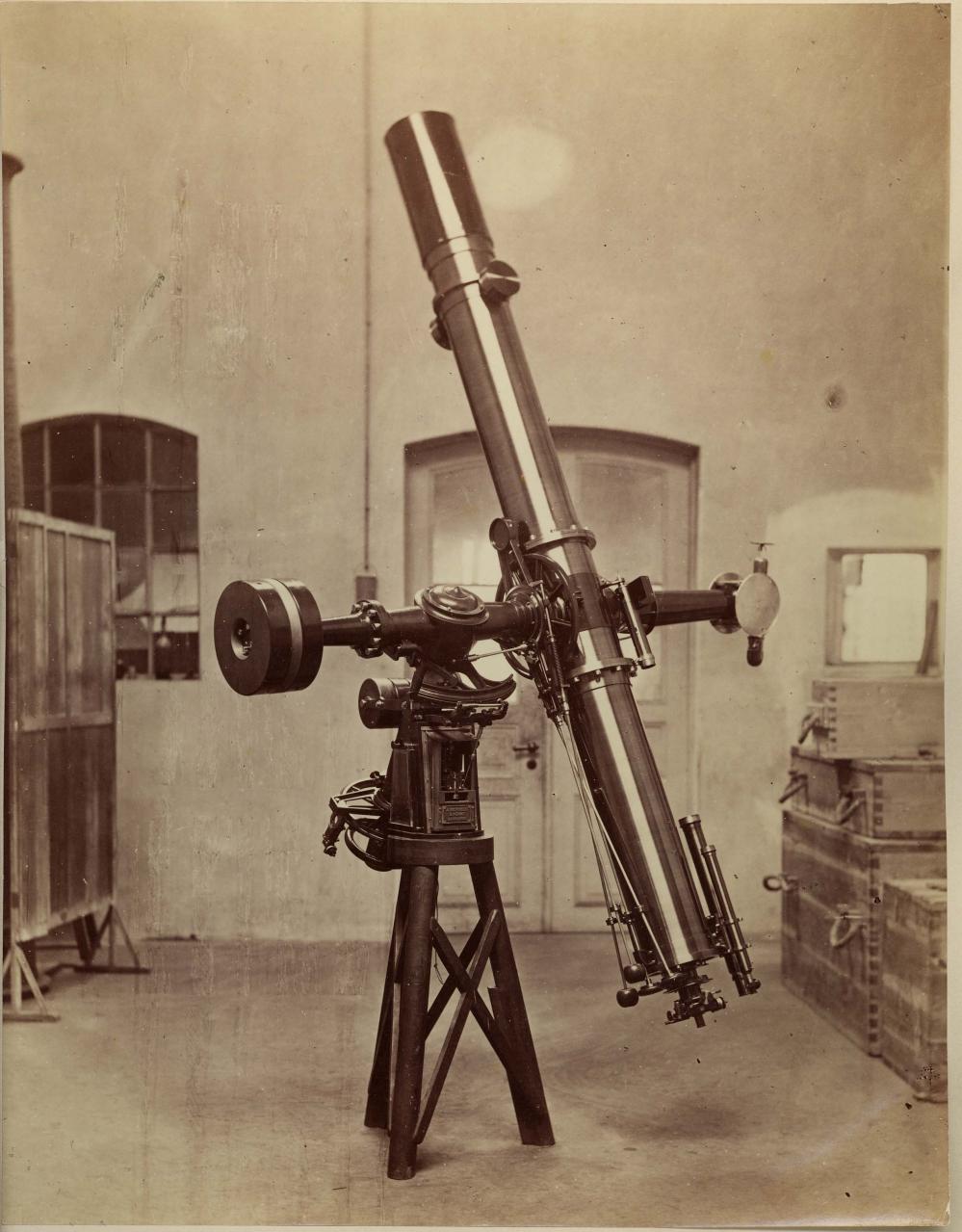

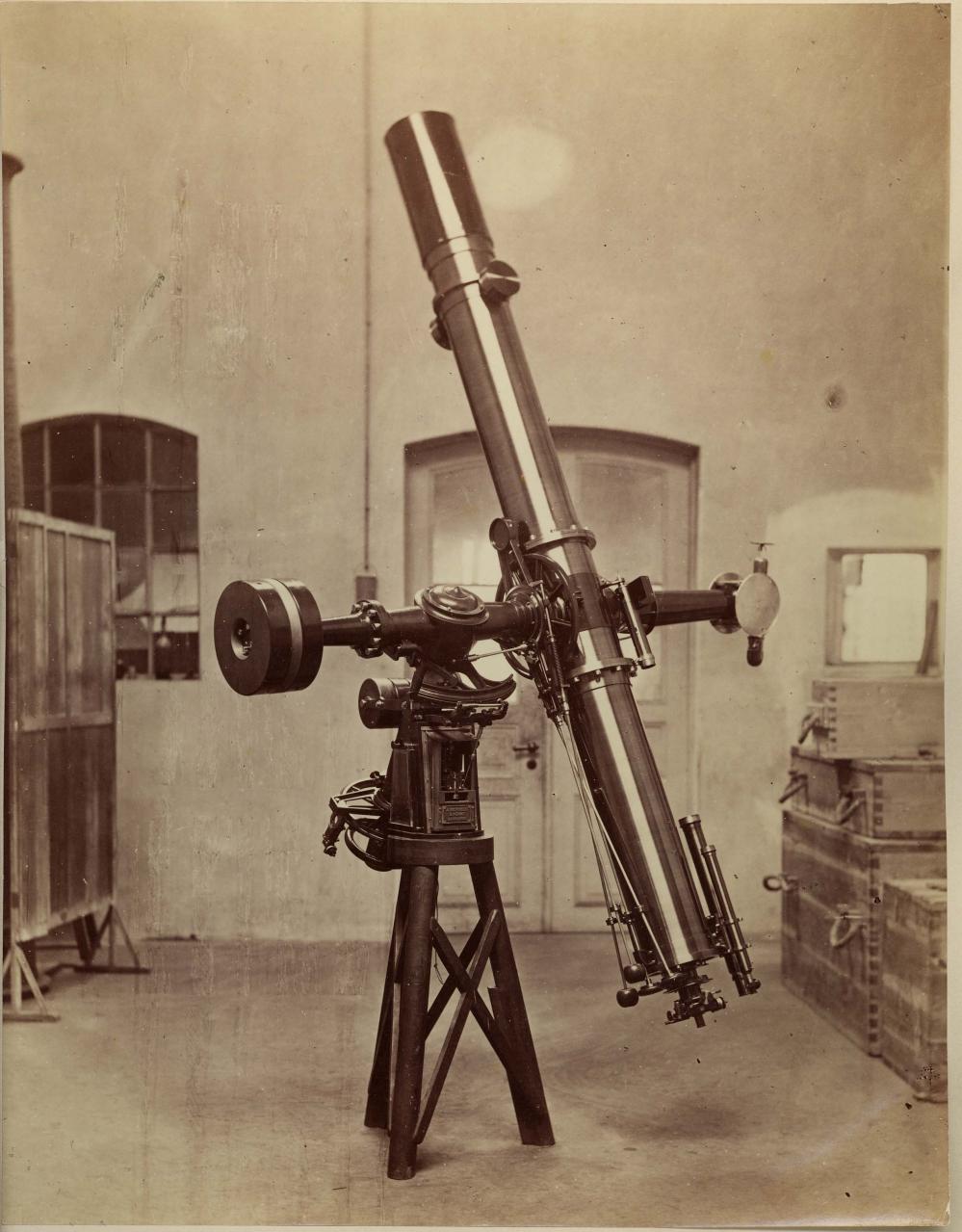

Fig. 4b. Refractor, mounting made by A. Repsold & Sons of Hamburg, optics made by Merz of Munich (1877) (© Inga Elmqvist Söderlund)

Instruments of Stockholm Observatory

- Timekeeping Instruments, pendulum clocks

- Meteorological Instruments

- Two small refractors

- Achromatic Refractor, John Dollond of London (1760)

- Quadrant, made by John Bird of London (1757)

- Gregorian Reflector, made by William Cary of London (ca. 1800)

- Meridian circle, Traugott Leberecht Ertel (1778--1858) of Munich (1830) [Mathematisch-mechanisches Institut T.L. Ertel since 1821]

- 7-inch Refractor with equatorial mounting, made by A. Repsold & Sons of Hamburg, optics made by Merz of Munich (1877),

used for parallax observations of bright stars. - 3-inch Astrograph, made by Steinheil of Munich (1880s)

- Telescope, Carl Zeiss of Jena (1910)

Instruments of Saltsjöbaden Observatory, Södermanland, 1931 to 2001

- Double telescope, 24/20-inch refractor, made by Grubb-Parsons of Newcastle upon Tyne (1931)

- 40-inch (102cm) Reflecting telescope, made by Grubb-Parsons of Newcastle upon Tyne (1931)

- Large Astrograph

- 1-m-Ritchey-Chrétien-Cassegrain-Reflecting-Telescope (11m focal length), made by Astro Optik, Germany (2007/09), in AlbaNova universitetscentrum on Roslagstull, operated in cooperation with the Department of Applied Physics at the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), funded by a grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Fig. 5a. Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin (1717--1783), Litho by Otto Henrik Wallgren (1795--1857) based on an original by Carl Friedrich Brander (1705--1779) (Wikipedia)

Fig. 5b. Hugo Gyldén (1841--1896) (Hildebrand: Sveriges historia, Wikipedia)

Directors

- Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin (1717--1783), 1749 to 1783

- ...

- Hugo Gyldén (1841--1896), 1871 to 1896

- Karl Petrus Theodor Bohlin (1860 --1939), 1897 to 1927

- Bertil Lindblad (1895--1965), 1927 to 1965

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:21:34

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6a. Carl Hårleman (1700--1753), by Johann Jakob Haid (Wikipedia)

Fig. 6b. Stockholm Observatory (1870s), built by Carl Hårleman, 1753 (© Inga Elmqvist Söderlund)

The Stockholm Observatory, built by Carl Hårleman (1753), is perfectly preserved. It is located on a hill above the city; this location, the architecture and the visibility showed the importance of the academy and of astronomy. The Stockholm Observatory is situated on a hill in a park, named Observatorielunden, surrounded by a walled garden with sculptures.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:27:05

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6c. Stockholm Observatory, interior observing room (Wikipedia, CC3-Brion-VIBBER)

The layout of the rooms of Stockholm Observatory is similar to the observatory of Kremsmünster, built just after it. Those two buildings, however, differ in the important aspect that the one in Kremsmünster is built as a very high tower.

In addition, King’s Observatory, Kew, Richmond (1769) and Gotha Observatory (1788) are very similar with the observing room in the ground floor. These observatories, Stockholm, Richmond and Gotha, later added a dome on the roof for a refractor.

One should also mention the Kassel tower observatory connected to the Fridericanum, built by Simon Louis Du Ry (1726--1799), inspired by Bologna Observatory, but Du Ry was also an apprentice of Hårleman, 1746 to 1748.

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-28 15:53:11

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no threats

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:19:52

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

After the move to Saltsjöbaden, the building of old Stockholm Observatory was sold to the City of Stockholm. It was then rented by the Department of Geography at Stockholm University; they remained until 1985. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences bought it back in 1999.

Today, the observatory dome at the top of the building has a telescope that was manufactured by Carl Zeiss of Jena in 1910, and which was originally set up in the observatory at Skansen. The entire top of the dome can be rotated using a hand crank.

Stockholm’s old observatory also has a new telescope in the nearby Magnet House, which Stockholm’s amateur astronomers use for observations.

Fig. 7. Observatoriemuseet (Wikipedia, CC3, Holger Ellgaard)

In 1991, a museum was inaugurated for permanent and temporary exhibitions. The permanent astronomical exhibition included Wargentin’s study, the Old and New Meridian Room, the Observation Hall with the instruments and the Venustransit model, the Clock Room, the the Weather Room, and the Natural History Cabinet. The Observatory Museum, which has been run first by the Observatory Hill Foundation and since 1999, by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, was closed in 2014.

In 2017, the Education Administration in the City of Stockholm wrote a letter of intent: "The City of Stockholm wants to create a unique platform for collaboration between schools, academia, museums and non-profit organizations." In April 2018, SISAB (School properties in Stockholm AB) acquired the property, thus it is again in city’s ownership. Together with the education administration and the House of Science, it is planned to open the Stockholm Observatory for students and teachers. The House of Science aims to increase children’s and young people’s interest and knowledge in science, technology and mathematics by hands-on activities in inspiring environment.

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:19:04

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Stockholm Observatory is no longer used for astronomy.

The research institute was transferred from the Academy to the Stockholm University in 1973.

Fig. 8a. Saltsjöbaden Observatory (1931) (Wikipedia, CC3, Irina Jonsson)

Fig. 8b. Saltsjöbaden Observatory (1931) (Wikipedia, CC3, Holger Ellgaard)

From 1931 to 2001, the Stockholm Observatory was located in the Saltsjöbaden.

Fig. 9a. Dome, AlbaNova University Centre, designed by Henning Larsen (2001) (© AlbaNova)

Fig. 9b. 1-m-Reflector, AlbaNova University Centre (© AlbaNova)

But after that the operations were moved to a new astronomy, physics and biotechnology center, AlbaNova University Centre, north of Roslagstull (59°21’14’’ N, 18°03’29’’ E); the main building was designed by Henning Larsen and in year 2001.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:16:16

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Alm, Henrik: Stockholms observatorium: Geografisk institution vid Stockholms universitet sedan 1934. Stockholm 1982, reprint of an article originally published in Samfundet St. Eriks årsbok. Stockholm 1930.

- Bergström, Cecilia & Inga Elmqvist Söderlund (ed.): Huset närmast himlen - Stockholms observatorium 250 år. Stockholm 2003.

- Bohlin, Karl: Todes-Anzeige [Hugo Gyldén]. In: Astronomische Nachrichten 142 (1897), 3388, Nr. 4, Sp. 49-52.

- Collinder, Per: Swedish astronomers 1477-1900. Uppsala

1970.

- Elmqvist Söderlund, Inga: The Old Stockholm Observatory in a Swedish Context and an Argument for the Necessity of an Inventory of the Swedish Astronomical Heritage. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Cultural Heritage of Astronomical Observatories -- From Classical Astronomy to Modern Astrophysics. Proceedings of the International ICOMOS Symposium in Hamburg, October 14-17, 2008. Berlin: hendrik Bäßler-Verlag (ICOMOS - International Council on Monuments and Sites XVIII) 2009, p. 234-249.

- Elmqvist Söderlund, Inga (1967--2017): The Old Stockholm Observatory in a Swedish Context. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Kiel 2015. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018, p. 326-349.

- Frängsmyr, Tore: Science in Sweden: The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 1739-1989. Canton 1989.

- Holmberg, Gustav: Astronomy in Sweden 1860--1940. In: Uppsala Newsletter: History of Science (1997), Nr. 26.

- Murdin, Paul: Lindblad, Bertil (1895--1965). (2001),

(doi:10.1888/0333750888/3815).

- Nordenmark, Nils Viktor Emanuel: Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin: Kungl. Vetenskapsakademiens sekreterare och astronom 1749-1783. Uppsala: Uppsala: Almquist & Wiksells 1939.

- Pipping, Gunnar: The chamber of physics. Stockholm 1991.

- Schmadel, Lutz D.: (806) Gyldénia. In: Dictionary of Minor Planet Names - (806) Gyldénia. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer 2007, p. 75 (doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_807).

- Sinnerstad, Ulf: Astronomy and the first observatory. In: Frängsmyr, Tore (ed.): Science in Sweden: The Royal Swedish academy of sciences 1739-1989. Canton 1989.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Kiel 2015. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Astronomie im Ostseeraum. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018, Astronomie in Schweden ab dem 18. Jahrhundert, p. 37-39.

Fig. 10. Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic (© Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:17:14

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Department of Astronomy at Stockholm University, Stockholm Observatory, AlbaNova University Center, Stockholms Universitet, SE-10691 Stockholm

- Department of Astronomy at Stockholm University

- About the telescope and the dome, Stockholm University, Department of Astronomy

- Insitute for Solar Physics, Stockholm University, Department of Astronomy - operates the Swedish 1-meter Solar Telescope (SST) on La Palma, currently the most highly resolving solar telescope in the world.

- Observatory Saltsjöbaden and its astrograph (Astrofriend’s homepage)

- Stockholm Observatory (Wikiwand)

- Stockholm Observatory, Stockholm, Sweden (Atlas Obscura)

- Fischer, Daniel: Ein kleines Juwel der Astronomiegeschichte: die Stockholmer Sternwarte aus dem 18. Jahrhundert,

"Pilgerfahrt" zu Stockholms Vädersolstavlan - Allgemeines Live-Blog vom 28. bis 30. Mai 2013

- AlbaNova University Centre (Wikipedia)

- AlbaNova University Centre

- Stockholm Historical Weather Observations

- Kozma, Cecilia: #66: Stockholms gamla observatorium. Svenska astronomiska sällskapet 100 år - Stort och smått från svensk astronomi under ett sekel (2019).

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-28 14:10:35

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Stockholms Observatorium, Observatorielunden, Drottninggatan 120, 113 60 Stockholm, Sweden

See also: 052 Saltsjöbaden Observatory (since 1931), Stockholm-Saltsjöbaden, Södermanland, Sweden

Location - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-28 15:49:11

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude 59°20’30’’ N, Longitude 18°03’17’’ E, Elevation ...m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-28 14:09:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

050

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 19:11:37

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 1a. Stockholm Observatory, built by Carl Hårleman, 1748-1753 (Wikipedia, CC3, I99pema, 2003)

Fig. 1b. Stockholm Observatory with a small turret, drawing by Olof Tempelman in 1797 (Center for History of Science at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences)

The Stockholm Observatory, the second oldest observatory in Sweden after the Celsiushuset in Uppsala (1741), was founded in 1748, built by Carl Hårleman (1700--1753) in Swedish rococo style, and inaugurated in 1753. Due to the high central body, the observatory building gets its character. The building’s circular room shape is marked in the bulge of the façade.

Hårleman had already designed the old Uppsala Observatory. Pehr Elvius the younger (1710--1749), a student of Anders Celsius (1701--1744) at Uppsala, was astronomer, founding member and secretary general to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (1739), had promoted the idea of a Stockholm Observatory.

Fig. 2. Stockholm old Observatory, round central room with 18th century instruments (Photo: Helen Pohl)

The design of the Stockholm old observatory is not a tower observatory, but a building with a main room for observations in the ground floor, this round central room was oriented towards the south. Exhibited are now (cf. Fig. 2) from the left a John Dollond achromatic refractor, which belonged to Samuel Klingenstierna (1698--1765), and was bought in 1760, a quadrant by John Bird from 1757, and a Gregorian reflector by William Cary, ca. 1800.

The long tradition in astrometry of Stockholm’s old observatory is shown in the a marble inlaid meridian line. It has previously served as the national zero meridian for Sweden, the position was 35°43’19.5’’ E Ferro, the international zero meridian of that time.

The Meridian Room was in the room farthest to the east, here Stockholm’s local time was determined. In the 1820s, when the premises were redistributed, these observations were moved to an adjoining room with a newly acquired telescope. These daily observations to determine local time and also Swedish time lasted until 1900, when they switched to GMT (Greenwich Mean Time); then the Swedish time had to be changed by 14 seconds.

In the ground floor were besides the observing rooms, the library, the offices for the astronomers, and a cabinet of naturalia, in the cellar, the workshop for instrument making. In the second and third floor were the appartments for the astronomers.

The first director was Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin (1717--1783), who became after his magister in philosophy in 1743 a docent in astronomy in 1746, and an adjunct in 1748. Then he served since 1749 for a long time as secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. His interest was observing the moons of Jupiter; the publication appeared: Specimen astronomicum, de satellitibus Jovis (Uppsala 1741).

An especially important activity of the Swedish astronomers were the transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769 with international cooperation.

Fig. 3. Observing the Venustransit (1761), model in Stockholm Observatory (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Remarkable research items are the records of daily weather observations from the observatory going back to 1756. In the Weather Chamber there is a temperature loop that shows the average temperature during the warmest (July) and coldest (February) month of the year from the 18th century, since Wargentin’s time, until today. Three times a day, temperature and rainfall have been measured at the observatory since 1756, and this is therefore the only place in the world, where the weather has been observed continuously for more than 250 years (air temperature, air pressure, rainfall, cloud amounts, snow depth). Today, the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI) is responsible for the measurements which are important for climate studies due to its long-term sustainable observational standards and high-quality time series data.

Fig. 3. Weather observations of Stockholm Observatory: The temperature loop begins 1756 and continues until today (Wikipedia, CC3, Holger Ellgaard)

In 1838 a magnetic house was built and magnetic measurements were started. The Stockholm Observatory was enlarged: An extension and a new tower with dome were built in 1875 by architect Johan Erik Söderlund, and in 1881 additional wings were built.

In the 19th century astrophysics started in Stockholm. Famous directors were Hugo Gyldén (1841--1896) from Helsinki, director since 1871, specialist in celestial mechanics and early promoter of astrophotography the 1880s, and Bertil Lindblad (1895--1965), director since 1927, who studied the theory of the rotation of galaxies. Due to the growing city and the deteriorating conditions for observations, Lindblad had to organize the observatory’s move from the old building in the centre of Stockholm to a newly built Saltsjöbaden Observatory on Karlsbaderberget, which was opened in 1931, designed by the architect Axel Anderberg.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 7

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 19:12:56

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 4a. Meridian circle, Traugott Leberecht Ertel (1778--1858) of Munich (1830) (© Inga Elmqvist Söderlund, Academy of Sciences)

Fig. 4b. Refractor, mounting made by A. Repsold & Sons of Hamburg, optics made by Merz of Munich (1877) (© Inga Elmqvist Söderlund)

Instruments of Stockholm Observatory

- Timekeeping Instruments, pendulum clocks

- Meteorological Instruments

- Two small refractors

- Achromatic Refractor, John Dollond of London (1760)

- Quadrant, made by John Bird of London (1757)

- Gregorian Reflector, made by William Cary of London (ca. 1800)

- Meridian circle, Traugott Leberecht Ertel (1778--1858) of Munich (1830) [Mathematisch-mechanisches Institut T.L. Ertel since 1821]

- 7-inch Refractor with equatorial mounting, made by A. Repsold & Sons of Hamburg, optics made by Merz of Munich (1877),

used for parallax observations of bright stars. - 3-inch Astrograph, made by Steinheil of Munich (1880s)

- Telescope, Carl Zeiss of Jena (1910)

Instruments of Saltsjöbaden Observatory, Södermanland, 1931 to 2001

- Double telescope, 24/20-inch refractor, made by Grubb-Parsons of Newcastle upon Tyne (1931)

- 40-inch (102cm) Reflecting telescope, made by Grubb-Parsons of Newcastle upon Tyne (1931)

- Large Astrograph

- 1-m-Ritchey-Chrétien-Cassegrain-Reflecting-Telescope (11m focal length), made by Astro Optik, Germany (2007/09), in AlbaNova universitetscentrum on Roslagstull, operated in cooperation with the Department of Applied Physics at the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), funded by a grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Fig. 5a. Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin (1717--1783), Litho by Otto Henrik Wallgren (1795--1857) based on an original by Carl Friedrich Brander (1705--1779) (Wikipedia)

Fig. 5b. Hugo Gyldén (1841--1896) (Hildebrand: Sveriges historia, Wikipedia)

Directors

- Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin (1717--1783), 1749 to 1783

- ...

- Hugo Gyldén (1841--1896), 1871 to 1896

- Karl Petrus Theodor Bohlin (1860 --1939), 1897 to 1927

- Bertil Lindblad (1895--1965), 1927 to 1965

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:21:34

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6a. Carl Hårleman (1700--1753), by Johann Jakob Haid (Wikipedia)

Fig. 6b. Stockholm Observatory (1870s), built by Carl Hårleman, 1753 (© Inga Elmqvist Söderlund)

The Stockholm Observatory, built by Carl Hårleman (1753), is perfectly preserved. It is located on a hill above the city; this location, the architecture and the visibility showed the importance of the academy and of astronomy. The Stockholm Observatory is situated on a hill in a park, named Observatorielunden, surrounded by a walled garden with sculptures.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:27:05

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6c. Stockholm Observatory, interior observing room (Wikipedia, CC3-Brion-VIBBER)

The layout of the rooms of Stockholm Observatory is similar to the observatory of Kremsmünster, built just after it. Those two buildings, however, differ in the important aspect that the one in Kremsmünster is built as a very high tower.

In addition, King’s Observatory, Kew, Richmond (1769) and Gotha Observatory (1788) are very similar with the observing room in the ground floor. These observatories, Stockholm, Richmond and Gotha, later added a dome on the roof for a refractor.

One should also mention the Kassel tower observatory connected to the Fridericanum, built by Simon Louis Du Ry (1726--1799), inspired by Bologna Observatory, but Du Ry was also an apprentice of Hårleman, 1746 to 1748.

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-28 15:53:11

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no threats

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:19:52

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

After the move to Saltsjöbaden, the building of old Stockholm Observatory was sold to the City of Stockholm. It was then rented by the Department of Geography at Stockholm University; they remained until 1985. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences bought it back in 1999.

Today, the observatory dome at the top of the building has a telescope that was manufactured by Carl Zeiss of Jena in 1910, and which was originally set up in the observatory at Skansen. The entire top of the dome can be rotated using a hand crank.

Stockholm’s old observatory also has a new telescope in the nearby Magnet House, which Stockholm’s amateur astronomers use for observations.

Fig. 7. Observatoriemuseet (Wikipedia, CC3, Holger Ellgaard)

In 1991, a museum was inaugurated for permanent and temporary exhibitions. The permanent astronomical exhibition included Wargentin’s study, the Old and New Meridian Room, the Observation Hall with the instruments and the Venustransit model, the Clock Room, the the Weather Room, and the Natural History Cabinet. The Observatory Museum, which has been run first by the Observatory Hill Foundation and since 1999, by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, was closed in 2014.

In 2017, the Education Administration in the City of Stockholm wrote a letter of intent: "The City of Stockholm wants to create a unique platform for collaboration between schools, academia, museums and non-profit organizations." In April 2018, SISAB (School properties in Stockholm AB) acquired the property, thus it is again in city’s ownership. Together with the education administration and the House of Science, it is planned to open the Stockholm Observatory for students and teachers. The House of Science aims to increase children’s and young people’s interest and knowledge in science, technology and mathematics by hands-on activities in inspiring environment.

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:19:04

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Stockholm Observatory is no longer used for astronomy.

The research institute was transferred from the Academy to the Stockholm University in 1973.

Fig. 8a. Saltsjöbaden Observatory (1931) (Wikipedia, CC3, Irina Jonsson)

Fig. 8b. Saltsjöbaden Observatory (1931) (Wikipedia, CC3, Holger Ellgaard)

From 1931 to 2001, the Stockholm Observatory was located in the Saltsjöbaden.

Fig. 9a. Dome, AlbaNova University Centre, designed by Henning Larsen (2001) (© AlbaNova)

Fig. 9b. 1-m-Reflector, AlbaNova University Centre (© AlbaNova)

But after that the operations were moved to a new astronomy, physics and biotechnology center, AlbaNova University Centre, north of Roslagstull (59°21’14’’ N, 18°03’29’’ E); the main building was designed by Henning Larsen and in year 2001.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:16:16

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Alm, Henrik: Stockholms observatorium: Geografisk institution vid Stockholms universitet sedan 1934. Stockholm 1982, reprint of an article originally published in Samfundet St. Eriks årsbok. Stockholm 1930.

- Bergström, Cecilia & Inga Elmqvist Söderlund (ed.): Huset närmast himlen - Stockholms observatorium 250 år. Stockholm 2003.

- Bohlin, Karl: Todes-Anzeige [Hugo Gyldén]. In: Astronomische Nachrichten 142 (1897), 3388, Nr. 4, Sp. 49-52.

- Collinder, Per: Swedish astronomers 1477-1900. Uppsala

1970.

- Elmqvist Söderlund, Inga: The Old Stockholm Observatory in a Swedish Context and an Argument for the Necessity of an Inventory of the Swedish Astronomical Heritage. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Cultural Heritage of Astronomical Observatories -- From Classical Astronomy to Modern Astrophysics. Proceedings of the International ICOMOS Symposium in Hamburg, October 14-17, 2008. Berlin: hendrik Bäßler-Verlag (ICOMOS - International Council on Monuments and Sites XVIII) 2009, p. 234-249.

- Elmqvist Söderlund, Inga (1967--2017): The Old Stockholm Observatory in a Swedish Context. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Kiel 2015. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018, p. 326-349.

- Frängsmyr, Tore: Science in Sweden: The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 1739-1989. Canton 1989.

- Holmberg, Gustav: Astronomy in Sweden 1860--1940. In: Uppsala Newsletter: History of Science (1997), Nr. 26.

- Murdin, Paul: Lindblad, Bertil (1895--1965). (2001),

(doi:10.1888/0333750888/3815).

- Nordenmark, Nils Viktor Emanuel: Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin: Kungl. Vetenskapsakademiens sekreterare och astronom 1749-1783. Uppsala: Uppsala: Almquist & Wiksells 1939.

- Pipping, Gunnar: The chamber of physics. Stockholm 1991.

- Schmadel, Lutz D.: (806) Gyldénia. In: Dictionary of Minor Planet Names - (806) Gyldénia. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer 2007, p. 75 (doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_807).

- Sinnerstad, Ulf: Astronomy and the first observatory. In: Frängsmyr, Tore (ed.): Science in Sweden: The Royal Swedish academy of sciences 1739-1989. Canton 1989.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Kiel 2015. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Astronomie im Ostseeraum. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018, Astronomie in Schweden ab dem 18. Jahrhundert, p. 37-39.

Fig. 10. Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic (© Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:17:14

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Department of Astronomy at Stockholm University, Stockholm Observatory, AlbaNova University Center, Stockholms Universitet, SE-10691 Stockholm

- Department of Astronomy at Stockholm University

- About the telescope and the dome, Stockholm University, Department of Astronomy

- Insitute for Solar Physics, Stockholm University, Department of Astronomy - operates the Swedish 1-meter Solar Telescope (SST) on La Palma, currently the most highly resolving solar telescope in the world.

- Observatory Saltsjöbaden and its astrograph (Astrofriend’s homepage)

- Stockholm Observatory (Wikiwand)

- Stockholm Observatory, Stockholm, Sweden (Atlas Obscura)

- Fischer, Daniel: Ein kleines Juwel der Astronomiegeschichte: die Stockholmer Sternwarte aus dem 18. Jahrhundert,

"Pilgerfahrt" zu Stockholms Vädersolstavlan - Allgemeines Live-Blog vom 28. bis 30. Mai 2013

- AlbaNova University Centre (Wikipedia)

- AlbaNova University Centre

- Stockholm Historical Weather Observations

- Kozma, Cecilia: #66: Stockholms gamla observatorium. Svenska astronomiska sällskapet 100 år - Stort och smått från svensk astronomi under ett sekel (2019).

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-28 15:49:11

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude 59°20’30’’ N, Longitude 18°03’17’’ E, Elevation ...m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-28 14:09:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

050

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 19:11:37

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 1a. Stockholm Observatory, built by Carl Hårleman, 1748-1753 (Wikipedia, CC3, I99pema, 2003)

Fig. 1b. Stockholm Observatory with a small turret, drawing by Olof Tempelman in 1797 (Center for History of Science at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences)

The Stockholm Observatory, the second oldest observatory in Sweden after the Celsiushuset in Uppsala (1741), was founded in 1748, built by Carl Hårleman (1700--1753) in Swedish rococo style, and inaugurated in 1753. Due to the high central body, the observatory building gets its character. The building’s circular room shape is marked in the bulge of the façade.

Hårleman had already designed the old Uppsala Observatory. Pehr Elvius the younger (1710--1749), a student of Anders Celsius (1701--1744) at Uppsala, was astronomer, founding member and secretary general to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (1739), had promoted the idea of a Stockholm Observatory.

Fig. 2. Stockholm old Observatory, round central room with 18th century instruments (Photo: Helen Pohl)

The design of the Stockholm old observatory is not a tower observatory, but a building with a main room for observations in the ground floor, this round central room was oriented towards the south. Exhibited are now (cf. Fig. 2) from the left a John Dollond achromatic refractor, which belonged to Samuel Klingenstierna (1698--1765), and was bought in 1760, a quadrant by John Bird from 1757, and a Gregorian reflector by William Cary, ca. 1800.

The long tradition in astrometry of Stockholm’s old observatory is shown in the a marble inlaid meridian line. It has previously served as the national zero meridian for Sweden, the position was 35°43’19.5’’ E Ferro, the international zero meridian of that time.

The Meridian Room was in the room farthest to the east, here Stockholm’s local time was determined. In the 1820s, when the premises were redistributed, these observations were moved to an adjoining room with a newly acquired telescope. These daily observations to determine local time and also Swedish time lasted until 1900, when they switched to GMT (Greenwich Mean Time); then the Swedish time had to be changed by 14 seconds.

In the ground floor were besides the observing rooms, the library, the offices for the astronomers, and a cabinet of naturalia, in the cellar, the workshop for instrument making. In the second and third floor were the appartments for the astronomers.

The first director was Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin (1717--1783), who became after his magister in philosophy in 1743 a docent in astronomy in 1746, and an adjunct in 1748. Then he served since 1749 for a long time as secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. His interest was observing the moons of Jupiter; the publication appeared: Specimen astronomicum, de satellitibus Jovis (Uppsala 1741).

An especially important activity of the Swedish astronomers were the transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769 with international cooperation.

Fig. 3. Observing the Venustransit (1761), model in Stockholm Observatory (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Remarkable research items are the records of daily weather observations from the observatory going back to 1756. In the Weather Chamber there is a temperature loop that shows the average temperature during the warmest (July) and coldest (February) month of the year from the 18th century, since Wargentin’s time, until today. Three times a day, temperature and rainfall have been measured at the observatory since 1756, and this is therefore the only place in the world, where the weather has been observed continuously for more than 250 years (air temperature, air pressure, rainfall, cloud amounts, snow depth). Today, the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI) is responsible for the measurements which are important for climate studies due to its long-term sustainable observational standards and high-quality time series data.

Fig. 3. Weather observations of Stockholm Observatory: The temperature loop begins 1756 and continues until today (Wikipedia, CC3, Holger Ellgaard)

In 1838 a magnetic house was built and magnetic measurements were started. The Stockholm Observatory was enlarged: An extension and a new tower with dome were built in 1875 by architect Johan Erik Söderlund, and in 1881 additional wings were built.

In the 19th century astrophysics started in Stockholm. Famous directors were Hugo Gyldén (1841--1896) from Helsinki, director since 1871, specialist in celestial mechanics and early promoter of astrophotography the 1880s, and Bertil Lindblad (1895--1965), director since 1927, who studied the theory of the rotation of galaxies. Due to the growing city and the deteriorating conditions for observations, Lindblad had to organize the observatory’s move from the old building in the centre of Stockholm to a newly built Saltsjöbaden Observatory on Karlsbaderberget, which was opened in 1931, designed by the architect Axel Anderberg.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 7

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 19:12:56

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 4a. Meridian circle, Traugott Leberecht Ertel (1778--1858) of Munich (1830) (© Inga Elmqvist Söderlund, Academy of Sciences)

Fig. 4b. Refractor, mounting made by A. Repsold & Sons of Hamburg, optics made by Merz of Munich (1877) (© Inga Elmqvist Söderlund)

Instruments of Stockholm Observatory

- Timekeeping Instruments, pendulum clocks

- Meteorological Instruments

- Two small refractors

- Achromatic Refractor, John Dollond of London (1760)

- Quadrant, made by John Bird of London (1757)

- Gregorian Reflector, made by William Cary of London (ca. 1800)

- Meridian circle, Traugott Leberecht Ertel (1778--1858) of Munich (1830) [Mathematisch-mechanisches Institut T.L. Ertel since 1821]

- 7-inch Refractor with equatorial mounting, made by A. Repsold & Sons of Hamburg, optics made by Merz of Munich (1877),

used for parallax observations of bright stars. - 3-inch Astrograph, made by Steinheil of Munich (1880s)

- Telescope, Carl Zeiss of Jena (1910)

Instruments of Saltsjöbaden Observatory, Södermanland, 1931 to 2001

- Double telescope, 24/20-inch refractor, made by Grubb-Parsons of Newcastle upon Tyne (1931)

- 40-inch (102cm) Reflecting telescope, made by Grubb-Parsons of Newcastle upon Tyne (1931)

- Large Astrograph

- 1-m-Ritchey-Chrétien-Cassegrain-Reflecting-Telescope (11m focal length), made by Astro Optik, Germany (2007/09), in AlbaNova universitetscentrum on Roslagstull, operated in cooperation with the Department of Applied Physics at the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), funded by a grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Fig. 5a. Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin (1717--1783), Litho by Otto Henrik Wallgren (1795--1857) based on an original by Carl Friedrich Brander (1705--1779) (Wikipedia)

Fig. 5b. Hugo Gyldén (1841--1896) (Hildebrand: Sveriges historia, Wikipedia)

Directors

- Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin (1717--1783), 1749 to 1783

- ...

- Hugo Gyldén (1841--1896), 1871 to 1896

- Karl Petrus Theodor Bohlin (1860 --1939), 1897 to 1927

- Bertil Lindblad (1895--1965), 1927 to 1965

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:21:34

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6a. Carl Hårleman (1700--1753), by Johann Jakob Haid (Wikipedia)

Fig. 6b. Stockholm Observatory (1870s), built by Carl Hårleman, 1753 (© Inga Elmqvist Söderlund)

The Stockholm Observatory, built by Carl Hårleman (1753), is perfectly preserved. It is located on a hill above the city; this location, the architecture and the visibility showed the importance of the academy and of astronomy. The Stockholm Observatory is situated on a hill in a park, named Observatorielunden, surrounded by a walled garden with sculptures.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:27:05

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6c. Stockholm Observatory, interior observing room (Wikipedia, CC3-Brion-VIBBER)

The layout of the rooms of Stockholm Observatory is similar to the observatory of Kremsmünster, built just after it. Those two buildings, however, differ in the important aspect that the one in Kremsmünster is built as a very high tower.

In addition, King’s Observatory, Kew, Richmond (1769) and Gotha Observatory (1788) are very similar with the observing room in the ground floor. These observatories, Stockholm, Richmond and Gotha, later added a dome on the roof for a refractor.

One should also mention the Kassel tower observatory connected to the Fridericanum, built by Simon Louis Du Ry (1726--1799), inspired by Bologna Observatory, but Du Ry was also an apprentice of Hårleman, 1746 to 1748.

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-28 15:53:11

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no threats

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:19:52

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

After the move to Saltsjöbaden, the building of old Stockholm Observatory was sold to the City of Stockholm. It was then rented by the Department of Geography at Stockholm University; they remained until 1985. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences bought it back in 1999.

Today, the observatory dome at the top of the building has a telescope that was manufactured by Carl Zeiss of Jena in 1910, and which was originally set up in the observatory at Skansen. The entire top of the dome can be rotated using a hand crank.

Stockholm’s old observatory also has a new telescope in the nearby Magnet House, which Stockholm’s amateur astronomers use for observations.

Fig. 7. Observatoriemuseet (Wikipedia, CC3, Holger Ellgaard)

In 1991, a museum was inaugurated for permanent and temporary exhibitions. The permanent astronomical exhibition included Wargentin’s study, the Old and New Meridian Room, the Observation Hall with the instruments and the Venustransit model, the Clock Room, the the Weather Room, and the Natural History Cabinet. The Observatory Museum, which has been run first by the Observatory Hill Foundation and since 1999, by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, was closed in 2014.

In 2017, the Education Administration in the City of Stockholm wrote a letter of intent: "The City of Stockholm wants to create a unique platform for collaboration between schools, academia, museums and non-profit organizations." In April 2018, SISAB (School properties in Stockholm AB) acquired the property, thus it is again in city’s ownership. Together with the education administration and the House of Science, it is planned to open the Stockholm Observatory for students and teachers. The House of Science aims to increase children’s and young people’s interest and knowledge in science, technology and mathematics by hands-on activities in inspiring environment.

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:19:04

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Stockholm Observatory is no longer used for astronomy.

The research institute was transferred from the Academy to the Stockholm University in 1973.

Fig. 8a. Saltsjöbaden Observatory (1931) (Wikipedia, CC3, Irina Jonsson)

Fig. 8b. Saltsjöbaden Observatory (1931) (Wikipedia, CC3, Holger Ellgaard)

From 1931 to 2001, the Stockholm Observatory was located in the Saltsjöbaden.

Fig. 9a. Dome, AlbaNova University Centre, designed by Henning Larsen (2001) (© AlbaNova)

Fig. 9b. 1-m-Reflector, AlbaNova University Centre (© AlbaNova)

But after that the operations were moved to a new astronomy, physics and biotechnology center, AlbaNova University Centre, north of Roslagstull (59°21’14’’ N, 18°03’29’’ E); the main building was designed by Henning Larsen and in year 2001.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:16:16

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Alm, Henrik: Stockholms observatorium: Geografisk institution vid Stockholms universitet sedan 1934. Stockholm 1982, reprint of an article originally published in Samfundet St. Eriks årsbok. Stockholm 1930.

- Bergström, Cecilia & Inga Elmqvist Söderlund (ed.): Huset närmast himlen - Stockholms observatorium 250 år. Stockholm 2003.

- Bohlin, Karl: Todes-Anzeige [Hugo Gyldén]. In: Astronomische Nachrichten 142 (1897), 3388, Nr. 4, Sp. 49-52.

- Collinder, Per: Swedish astronomers 1477-1900. Uppsala

1970.

- Elmqvist Söderlund, Inga: The Old Stockholm Observatory in a Swedish Context and an Argument for the Necessity of an Inventory of the Swedish Astronomical Heritage. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Cultural Heritage of Astronomical Observatories -- From Classical Astronomy to Modern Astrophysics. Proceedings of the International ICOMOS Symposium in Hamburg, October 14-17, 2008. Berlin: hendrik Bäßler-Verlag (ICOMOS - International Council on Monuments and Sites XVIII) 2009, p. 234-249.

- Elmqvist Söderlund, Inga (1967--2017): The Old Stockholm Observatory in a Swedish Context. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Kiel 2015. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018, p. 326-349.

- Frängsmyr, Tore: Science in Sweden: The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 1739-1989. Canton 1989.

- Holmberg, Gustav: Astronomy in Sweden 1860--1940. In: Uppsala Newsletter: History of Science (1997), Nr. 26.

- Murdin, Paul: Lindblad, Bertil (1895--1965). (2001),

(doi:10.1888/0333750888/3815).

- Nordenmark, Nils Viktor Emanuel: Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin: Kungl. Vetenskapsakademiens sekreterare och astronom 1749-1783. Uppsala: Uppsala: Almquist & Wiksells 1939.

- Pipping, Gunnar: The chamber of physics. Stockholm 1991.

- Schmadel, Lutz D.: (806) Gyldénia. In: Dictionary of Minor Planet Names - (806) Gyldénia. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer 2007, p. 75 (doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_807).

- Sinnerstad, Ulf: Astronomy and the first observatory. In: Frängsmyr, Tore (ed.): Science in Sweden: The Royal Swedish academy of sciences 1739-1989. Canton 1989.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Kiel 2015. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Astronomie im Ostseeraum. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018, Astronomie in Schweden ab dem 18. Jahrhundert, p. 37-39.

Fig. 10. Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic (© Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:17:14

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Department of Astronomy at Stockholm University, Stockholm Observatory, AlbaNova University Center, Stockholms Universitet, SE-10691 Stockholm

- Department of Astronomy at Stockholm University

- About the telescope and the dome, Stockholm University, Department of Astronomy

- Insitute for Solar Physics, Stockholm University, Department of Astronomy - operates the Swedish 1-meter Solar Telescope (SST) on La Palma, currently the most highly resolving solar telescope in the world.

- Observatory Saltsjöbaden and its astrograph (Astrofriend’s homepage)

- Stockholm Observatory (Wikiwand)

- Stockholm Observatory, Stockholm, Sweden (Atlas Obscura)

- Fischer, Daniel: Ein kleines Juwel der Astronomiegeschichte: die Stockholmer Sternwarte aus dem 18. Jahrhundert,

"Pilgerfahrt" zu Stockholms Vädersolstavlan - Allgemeines Live-Blog vom 28. bis 30. Mai 2013

- AlbaNova University Centre (Wikipedia)

- AlbaNova University Centre

- Stockholm Historical Weather Observations

- Kozma, Cecilia: #66: Stockholms gamla observatorium. Svenska astronomiska sällskapet 100 år - Stort och smått från svensk astronomi under ett sekel (2019).

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-28 14:09:08

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

050

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 19:11:37

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 1a. Stockholm Observatory, built by Carl Hårleman, 1748-1753 (Wikipedia, CC3, I99pema, 2003)

Fig. 1b. Stockholm Observatory with a small turret, drawing by Olof Tempelman in 1797 (Center for History of Science at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences)

The Stockholm Observatory, the second oldest observatory in Sweden after the Celsiushuset in Uppsala (1741), was founded in 1748, built by Carl Hårleman (1700--1753) in Swedish rococo style, and inaugurated in 1753. Due to the high central body, the observatory building gets its character. The building’s circular room shape is marked in the bulge of the façade.

Hårleman had already designed the old Uppsala Observatory. Pehr Elvius the younger (1710--1749), a student of Anders Celsius (1701--1744) at Uppsala, was astronomer, founding member and secretary general to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (1739), had promoted the idea of a Stockholm Observatory.

Fig. 2. Stockholm old Observatory, round central room with 18th century instruments (Photo: Helen Pohl)

The design of the Stockholm old observatory is not a tower observatory, but a building with a main room for observations in the ground floor, this round central room was oriented towards the south. Exhibited are now (cf. Fig. 2) from the left a John Dollond achromatic refractor, which belonged to Samuel Klingenstierna (1698--1765), and was bought in 1760, a quadrant by John Bird from 1757, and a Gregorian reflector by William Cary, ca. 1800.

The long tradition in astrometry of Stockholm’s old observatory is shown in the a marble inlaid meridian line. It has previously served as the national zero meridian for Sweden, the position was 35°43’19.5’’ E Ferro, the international zero meridian of that time.

The Meridian Room was in the room farthest to the east, here Stockholm’s local time was determined. In the 1820s, when the premises were redistributed, these observations were moved to an adjoining room with a newly acquired telescope. These daily observations to determine local time and also Swedish time lasted until 1900, when they switched to GMT (Greenwich Mean Time); then the Swedish time had to be changed by 14 seconds.

In the ground floor were besides the observing rooms, the library, the offices for the astronomers, and a cabinet of naturalia, in the cellar, the workshop for instrument making. In the second and third floor were the appartments for the astronomers.

The first director was Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin (1717--1783), who became after his magister in philosophy in 1743 a docent in astronomy in 1746, and an adjunct in 1748. Then he served since 1749 for a long time as secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. His interest was observing the moons of Jupiter; the publication appeared: Specimen astronomicum, de satellitibus Jovis (Uppsala 1741).

An especially important activity of the Swedish astronomers were the transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769 with international cooperation.

Fig. 3. Observing the Venustransit (1761), model in Stockholm Observatory (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Remarkable research items are the records of daily weather observations from the observatory going back to 1756. In the Weather Chamber there is a temperature loop that shows the average temperature during the warmest (July) and coldest (February) month of the year from the 18th century, since Wargentin’s time, until today. Three times a day, temperature and rainfall have been measured at the observatory since 1756, and this is therefore the only place in the world, where the weather has been observed continuously for more than 250 years (air temperature, air pressure, rainfall, cloud amounts, snow depth). Today, the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI) is responsible for the measurements which are important for climate studies due to its long-term sustainable observational standards and high-quality time series data.

Fig. 3. Weather observations of Stockholm Observatory: The temperature loop begins 1756 and continues until today (Wikipedia, CC3, Holger Ellgaard)

In 1838 a magnetic house was built and magnetic measurements were started. The Stockholm Observatory was enlarged: An extension and a new tower with dome were built in 1875 by architect Johan Erik Söderlund, and in 1881 additional wings were built.

In the 19th century astrophysics started in Stockholm. Famous directors were Hugo Gyldén (1841--1896) from Helsinki, director since 1871, specialist in celestial mechanics and early promoter of astrophotography the 1880s, and Bertil Lindblad (1895--1965), director since 1927, who studied the theory of the rotation of galaxies. Due to the growing city and the deteriorating conditions for observations, Lindblad had to organize the observatory’s move from the old building in the centre of Stockholm to a newly built Saltsjöbaden Observatory on Karlsbaderberget, which was opened in 1931, designed by the architect Axel Anderberg.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 7

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 19:12:56

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 4a. Meridian circle, Traugott Leberecht Ertel (1778--1858) of Munich (1830) (© Inga Elmqvist Söderlund, Academy of Sciences)

Fig. 4b. Refractor, mounting made by A. Repsold & Sons of Hamburg, optics made by Merz of Munich (1877) (© Inga Elmqvist Söderlund)

Instruments of Stockholm Observatory

- Timekeeping Instruments, pendulum clocks

- Meteorological Instruments

- Two small refractors

- Achromatic Refractor, John Dollond of London (1760)

- Quadrant, made by John Bird of London (1757)

- Gregorian Reflector, made by William Cary of London (ca. 1800)

- Meridian circle, Traugott Leberecht Ertel (1778--1858) of Munich (1830) [Mathematisch-mechanisches Institut T.L. Ertel since 1821]

- 7-inch Refractor with equatorial mounting, made by A. Repsold & Sons of Hamburg, optics made by Merz of Munich (1877),

used for parallax observations of bright stars. - 3-inch Astrograph, made by Steinheil of Munich (1880s)

- Telescope, Carl Zeiss of Jena (1910)

Instruments of Saltsjöbaden Observatory, Södermanland, 1931 to 2001

- Double telescope, 24/20-inch refractor, made by Grubb-Parsons of Newcastle upon Tyne (1931)

- 40-inch (102cm) Reflecting telescope, made by Grubb-Parsons of Newcastle upon Tyne (1931)

- Large Astrograph

- 1-m-Ritchey-Chrétien-Cassegrain-Reflecting-Telescope (11m focal length), made by Astro Optik, Germany (2007/09), in AlbaNova universitetscentrum on Roslagstull, operated in cooperation with the Department of Applied Physics at the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), funded by a grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Fig. 5a. Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin (1717--1783), Litho by Otto Henrik Wallgren (1795--1857) based on an original by Carl Friedrich Brander (1705--1779) (Wikipedia)

Fig. 5b. Hugo Gyldén (1841--1896) (Hildebrand: Sveriges historia, Wikipedia)

Directors

- Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin (1717--1783), 1749 to 1783

- ...

- Hugo Gyldén (1841--1896), 1871 to 1896

- Karl Petrus Theodor Bohlin (1860 --1939), 1897 to 1927

- Bertil Lindblad (1895--1965), 1927 to 1965

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:21:34

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6a. Carl Hårleman (1700--1753), by Johann Jakob Haid (Wikipedia)

Fig. 6b. Stockholm Observatory (1870s), built by Carl Hårleman, 1753 (© Inga Elmqvist Söderlund)

The Stockholm Observatory, built by Carl Hårleman (1753), is perfectly preserved. It is located on a hill above the city; this location, the architecture and the visibility showed the importance of the academy and of astronomy. The Stockholm Observatory is situated on a hill in a park, named Observatorielunden, surrounded by a walled garden with sculptures.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:27:05

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6c. Stockholm Observatory, interior observing room (Wikipedia, CC3-Brion-VIBBER)

The layout of the rooms of Stockholm Observatory is similar to the observatory of Kremsmünster, built just after it. Those two buildings, however, differ in the important aspect that the one in Kremsmünster is built as a very high tower.

In addition, King’s Observatory, Kew, Richmond (1769) and Gotha Observatory (1788) are very similar with the observing room in the ground floor. These observatories, Stockholm, Richmond and Gotha, later added a dome on the roof for a refractor.

One should also mention the Kassel tower observatory connected to the Fridericanum, built by Simon Louis Du Ry (1726--1799), inspired by Bologna Observatory, but Du Ry was also an apprentice of Hårleman, 1746 to 1748.

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-28 15:53:11

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no threats

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:19:52

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

After the move to Saltsjöbaden, the building of old Stockholm Observatory was sold to the City of Stockholm. It was then rented by the Department of Geography at Stockholm University; they remained until 1985. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences bought it back in 1999.

Today, the observatory dome at the top of the building has a telescope that was manufactured by Carl Zeiss of Jena in 1910, and which was originally set up in the observatory at Skansen. The entire top of the dome can be rotated using a hand crank.

Stockholm’s old observatory also has a new telescope in the nearby Magnet House, which Stockholm’s amateur astronomers use for observations.

Fig. 7. Observatoriemuseet (Wikipedia, CC3, Holger Ellgaard)

In 1991, a museum was inaugurated for permanent and temporary exhibitions. The permanent astronomical exhibition included Wargentin’s study, the Old and New Meridian Room, the Observation Hall with the instruments and the Venustransit model, the Clock Room, the the Weather Room, and the Natural History Cabinet. The Observatory Museum, which has been run first by the Observatory Hill Foundation and since 1999, by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, was closed in 2014.

In 2017, the Education Administration in the City of Stockholm wrote a letter of intent: "The City of Stockholm wants to create a unique platform for collaboration between schools, academia, museums and non-profit organizations." In April 2018, SISAB (School properties in Stockholm AB) acquired the property, thus it is again in city’s ownership. Together with the education administration and the House of Science, it is planned to open the Stockholm Observatory for students and teachers. The House of Science aims to increase children’s and young people’s interest and knowledge in science, technology and mathematics by hands-on activities in inspiring environment.

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:19:04

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Stockholm Observatory is no longer used for astronomy.

The research institute was transferred from the Academy to the Stockholm University in 1973.

Fig. 8a. Saltsjöbaden Observatory (1931) (Wikipedia, CC3, Irina Jonsson)

Fig. 8b. Saltsjöbaden Observatory (1931) (Wikipedia, CC3, Holger Ellgaard)

From 1931 to 2001, the Stockholm Observatory was located in the Saltsjöbaden.

Fig. 9a. Dome, AlbaNova University Centre, designed by Henning Larsen (2001) (© AlbaNova)

Fig. 9b. 1-m-Reflector, AlbaNova University Centre (© AlbaNova)

But after that the operations were moved to a new astronomy, physics and biotechnology center, AlbaNova University Centre, north of Roslagstull (59°21’14’’ N, 18°03’29’’ E); the main building was designed by Henning Larsen and in year 2001.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:16:16

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Alm, Henrik: Stockholms observatorium: Geografisk institution vid Stockholms universitet sedan 1934. Stockholm 1982, reprint of an article originally published in Samfundet St. Eriks årsbok. Stockholm 1930.

- Bergström, Cecilia & Inga Elmqvist Söderlund (ed.): Huset närmast himlen - Stockholms observatorium 250 år. Stockholm 2003.

- Bohlin, Karl: Todes-Anzeige [Hugo Gyldén]. In: Astronomische Nachrichten 142 (1897), 3388, Nr. 4, Sp. 49-52.

- Collinder, Per: Swedish astronomers 1477-1900. Uppsala

1970.

- Elmqvist Söderlund, Inga: The Old Stockholm Observatory in a Swedish Context and an Argument for the Necessity of an Inventory of the Swedish Astronomical Heritage. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Cultural Heritage of Astronomical Observatories -- From Classical Astronomy to Modern Astrophysics. Proceedings of the International ICOMOS Symposium in Hamburg, October 14-17, 2008. Berlin: hendrik Bäßler-Verlag (ICOMOS - International Council on Monuments and Sites XVIII) 2009, p. 234-249.

- Elmqvist Söderlund, Inga (1967--2017): The Old Stockholm Observatory in a Swedish Context. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Kiel 2015. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018, p. 326-349.

- Frängsmyr, Tore: Science in Sweden: The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 1739-1989. Canton 1989.

- Holmberg, Gustav: Astronomy in Sweden 1860--1940. In: Uppsala Newsletter: History of Science (1997), Nr. 26.

- Murdin, Paul: Lindblad, Bertil (1895--1965). (2001),

(doi:10.1888/0333750888/3815).

- Nordenmark, Nils Viktor Emanuel: Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin: Kungl. Vetenskapsakademiens sekreterare och astronom 1749-1783. Uppsala: Uppsala: Almquist & Wiksells 1939.

- Pipping, Gunnar: The chamber of physics. Stockholm 1991.

- Schmadel, Lutz D.: (806) Gyldénia. In: Dictionary of Minor Planet Names - (806) Gyldénia. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer 2007, p. 75 (doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_807).

- Sinnerstad, Ulf: Astronomy and the first observatory. In: Frängsmyr, Tore (ed.): Science in Sweden: The Royal Swedish academy of sciences 1739-1989. Canton 1989.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Kiel 2015. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Astronomie im Ostseeraum. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 38) 2018, Astronomie in Schweden ab dem 18. Jahrhundert, p. 37-39.

Fig. 10. Astronomie im Ostseeraum -- Astronomy in the Baltic (© Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 20:17:14

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Department of Astronomy at Stockholm University, Stockholm Observatory, AlbaNova University Center, Stockholms Universitet, SE-10691 Stockholm

- Department of Astronomy at Stockholm University

- About the telescope and the dome, Stockholm University, Department of Astronomy

- Insitute for Solar Physics, Stockholm University, Department of Astronomy - operates the Swedish 1-meter Solar Telescope (SST) on La Palma, currently the most highly resolving solar telescope in the world.

- Observatory Saltsjöbaden and its astrograph (Astrofriend’s homepage)

- Stockholm Observatory (Wikiwand)

- Stockholm Observatory, Stockholm, Sweden (Atlas Obscura)

- Fischer, Daniel: Ein kleines Juwel der Astronomiegeschichte: die Stockholmer Sternwarte aus dem 18. Jahrhundert,

"Pilgerfahrt" zu Stockholms Vädersolstavlan - Allgemeines Live-Blog vom 28. bis 30. Mai 2013

- AlbaNova University Centre (Wikipedia)

- AlbaNova University Centre

- Stockholm Historical Weather Observations

- Kozma, Cecilia: #66: Stockholms gamla observatorium. Svenska astronomiska sällskapet 100 år - Stort och smått från svensk astronomi under ett sekel (2019).

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 209

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-05 19:11:37

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 1a. Stockholm Observatory, built by Carl Hårleman, 1748-1753 (Wikipedia, CC3, I99pema, 2003)

Fig. 1b. Stockholm Observatory with a small turret, drawing by Olof Tempelman in 1797 (Center for History of Science at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences)

The Stockholm Observatory, the second oldest observatory in Sweden after the Celsiushuset in Uppsala (1741), was founded in 1748, built by Carl Hårleman (1700--1753) in Swedish rococo style, and inaugurated in 1753. Due to the high central body, the observatory building gets its character. The building’s circular room shape is marked in the bulge of the façade.

Hårleman had already designed the old Uppsala Observatory. Pehr Elvius the younger (1710--1749), a student of Anders Celsius (1701--1744) at Uppsala, was astronomer, founding member and secretary general to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (1739), had promoted the idea of a Stockholm Observatory.

Fig. 2. Stockholm old Observatory, round central room with 18th century instruments (Photo: Helen Pohl)

The design of the Stockholm old observatory is not a tower observatory, but a building with a main room for observations in the ground floor, this round central room was oriented towards the south. Exhibited are now (cf. Fig. 2) from the left a John Dollond achromatic refractor, which belonged to Samuel Klingenstierna (1698--1765), and was bought in 1760, a quadrant by John Bird from 1757, and a Gregorian reflector by William Cary, ca. 1800.

The long tradition in astrometry of Stockholm’s old observatory is shown in the a marble inlaid meridian line. It has previously served as the national zero meridian for Sweden, the position was 35°43’19.5’’ E Ferro, the international zero meridian of that time.

The Meridian Room was in the room farthest to the east, here Stockholm’s local time was determined. In the 1820s, when the premises were redistributed, these observations were moved to an adjoining room with a newly acquired telescope. These daily observations to determine local time and also Swedish time lasted until 1900, when they switched to GMT (Greenwich Mean Time); then the Swedish time had to be changed by 14 seconds.

In the ground floor were besides the observing rooms, the library, the offices for the astronomers, and a cabinet of naturalia, in the cellar, the workshop for instrument making. In the second and third floor were the appartments for the astronomers.

The first director was Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin (1717--1783), who became after his magister in philosophy in 1743 a docent in astronomy in 1746, and an adjunct in 1748. Then he served since 1749 for a long time as secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. His interest was observing the moons of Jupiter; the publication appeared: Specimen astronomicum, de satellitibus Jovis (Uppsala 1741).

An especially important activity of the Swedish astronomers were the transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769 with international cooperation.

Fig. 3. Observing the Venustransit (1761), model in Stockholm Observatory (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Remarkable research items are the records of daily weather observations from the observatory going back to 1756. In the Weather Chamber there is a temperature loop that shows the average temperature during the warmest (July) and coldest (February) month of the year from the 18th century, since Wargentin’s time, until today. Three times a day, temperature and rainfall have been measured at the observatory since 1756, and this is therefore the only place in the world, where the weather has been observed continuously for more than 250 years (air temperature, air pressure, rainfall, cloud amounts, snow depth). Today, the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI) is responsible for the measurements which are important for climate studies due to its long-term sustainable observational standards and high-quality time series data.

Fig. 3. Weather observations of Stockholm Observatory: The temperature loop begins 1756 and continues until today (Wikipedia, CC3, Holger Ellgaard)

In 1838 a magnetic house was built and magnetic measurements were started. The Stockholm Observatory was enlarged: An extension and a new tower with dome were built in 1875 by architect Johan Erik Söderlund, and in 1881 additional wings were built.