Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Marinoni Observatory, Mölkerbastei, Vienna, Austria

Format: IAU - Outstanding Astronomical Heritage

Description

Geographical position - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-05-28 03:02:45

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Marinoni Observatory, Mölkerbastei 8, Schreyvogelgasse 16, 1010 Vienna, Austria

(today Pasqualati building)

See also: Observatories in Vienna in the 18th and 19th Century:

- Vienna Jesuit Observatory (1733)

- Old Vienna University Observatory (1754--1879), today Austrian Academy of Sciences

- Kuffner Observatory, Vienna-Ottakring (1886)

- Vienna University Observatory, Wien-Währing (1879)

Location - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 19:43:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude +48°12.7’ N, Longitude 16°21.7’ E, Elevation 180m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 18:32:57

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

-

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-31 16:12:15

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

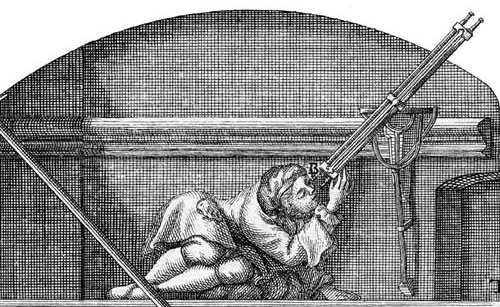

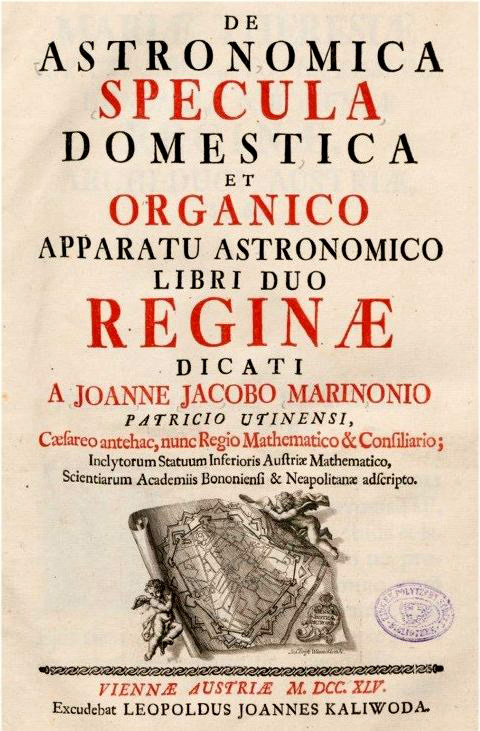

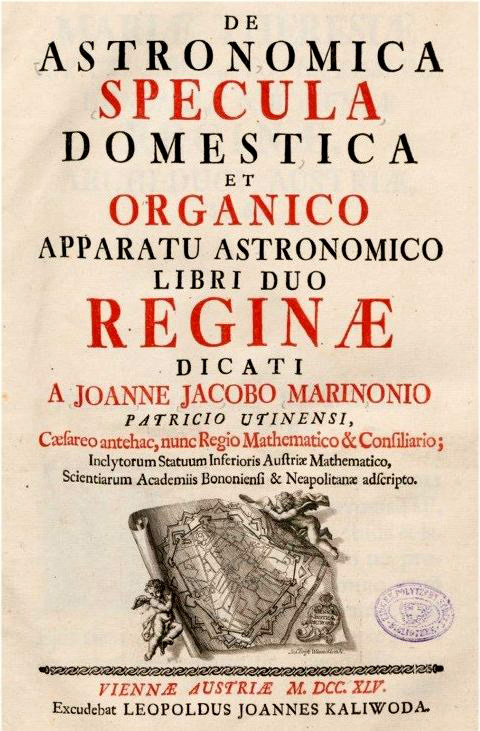

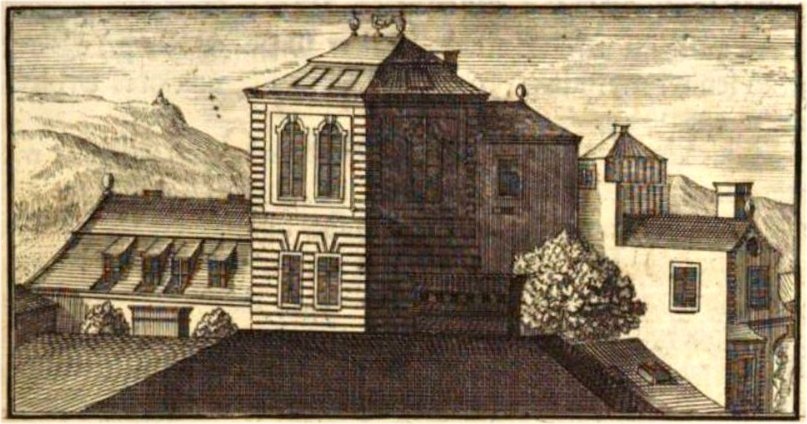

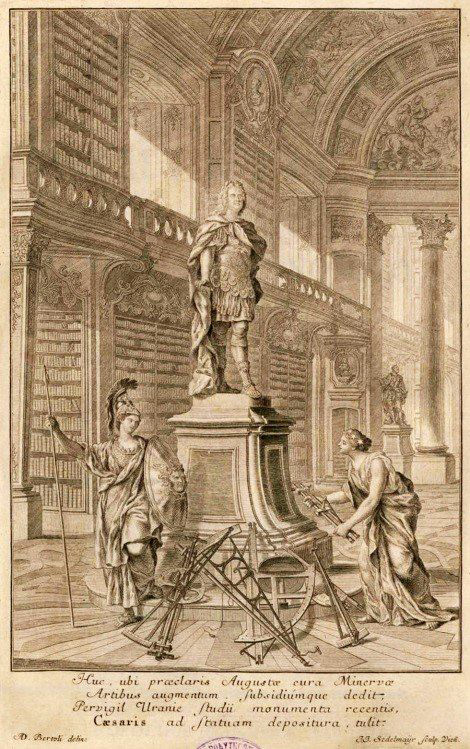

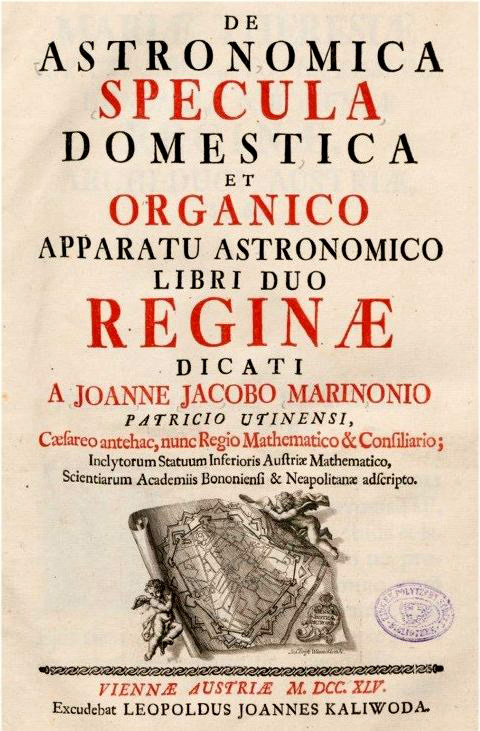

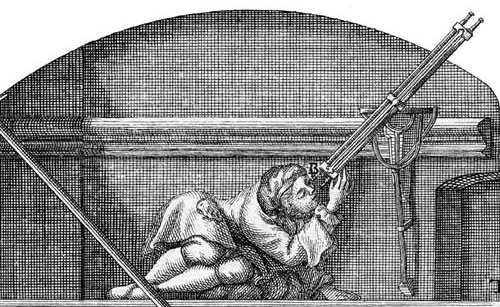

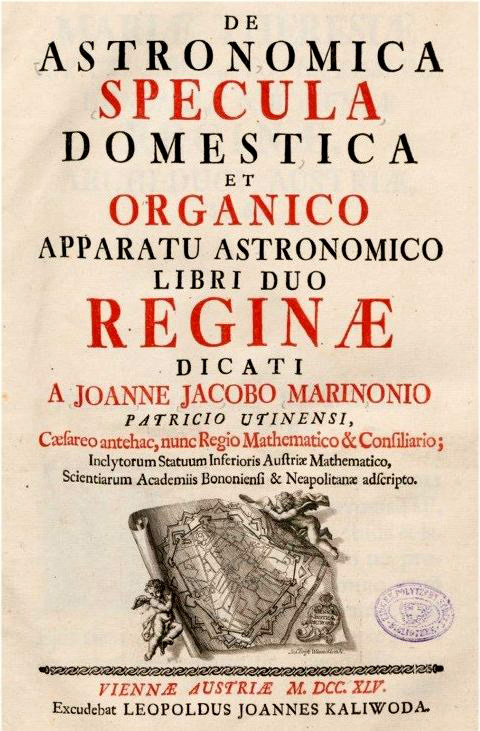

Fig. 1a. Marinoni’s private observatory ("De astronomica specula domestica et organico apparatu astronomico" (Wien: Kaliwoda 1745)

Giovanni Jacopo de Marinoni (1676--1755) and his Observatory

![Johann Jakob von [Giovanni Jacopo de] Marinoni (16](/images/astronomicalheritage.net/gallery/ahp_entities/entity000220/H+K_01.jpg)

Fig. 1b. Johann Jakob von [Giovanni Jacopo de] Marinoni (1676--1755), engraving by Ferdinand Landerer, undated (Bildarchiv der ÖNB, © ÖNB Wien, PORT_001211305_01AZ:27249/3/2017)

Fig. 1c. Coat of arms of Giovanni Jacopo de Marinoni (1676--1755) (Nobility Patent of Marinoni)

Giovanni Jacopo de [Johann Jakob] Marinoni (1676--1755) was born in Udine. In 1703, Emperor Leopold I gave him the title of court mathematician, which was confirmed by the following rulers Joseph I, Charles VI, and Maria Theresa until the end of his life.

The Imperial court mathematician erected in the 1720s in Vienna with Imperial support on the roof of his house on the Mölkerbastei (medieval bastion) a two-story tower, which he expanded to an observatory. This private observatory, which he describes in detail in his book, was actually the first observatory in Vienna.

Marinoni was knighted on April 9, 1733. Then, on April 22, 1733, Marinoni was appointed head of the Mathematical and Engineering Academy.

Founding of the first Polytechnical School in Central Europe

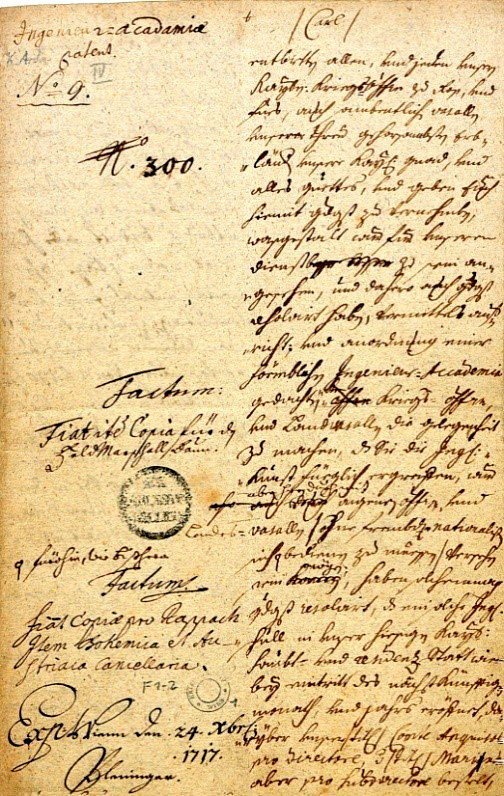

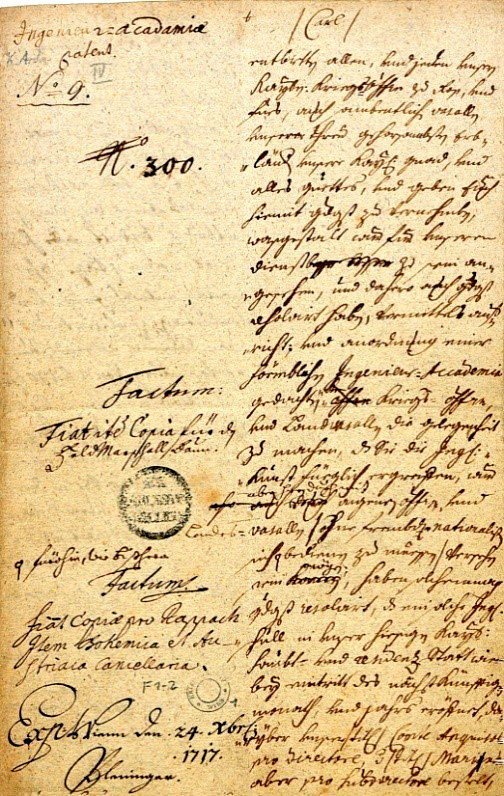

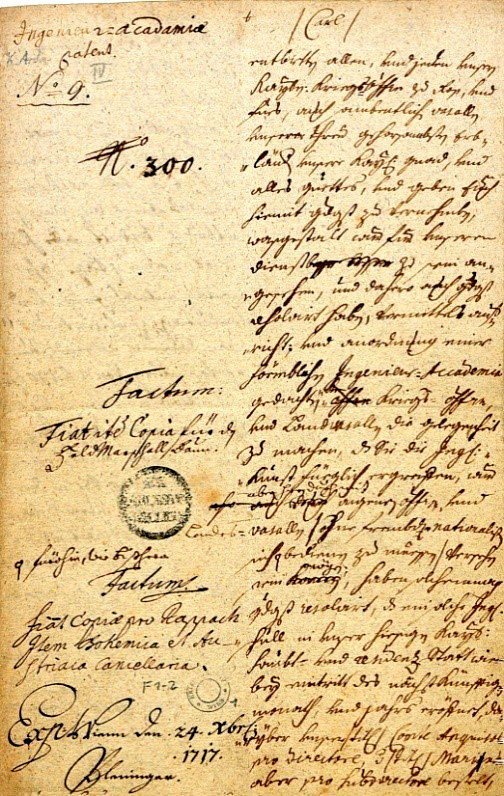

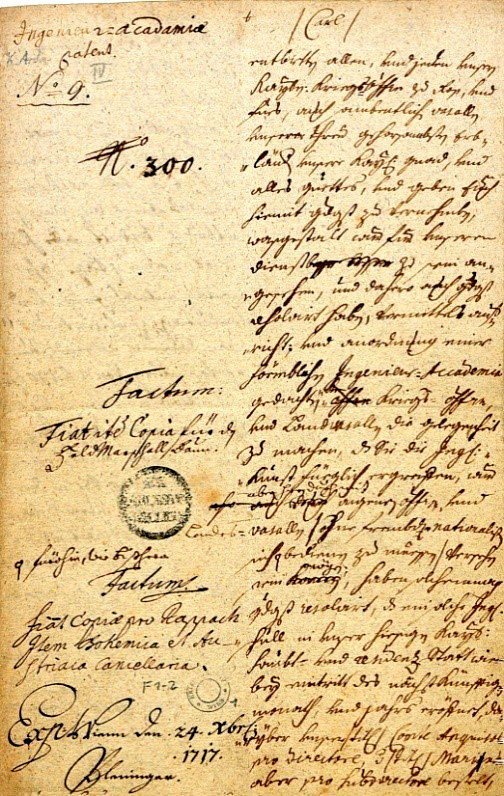

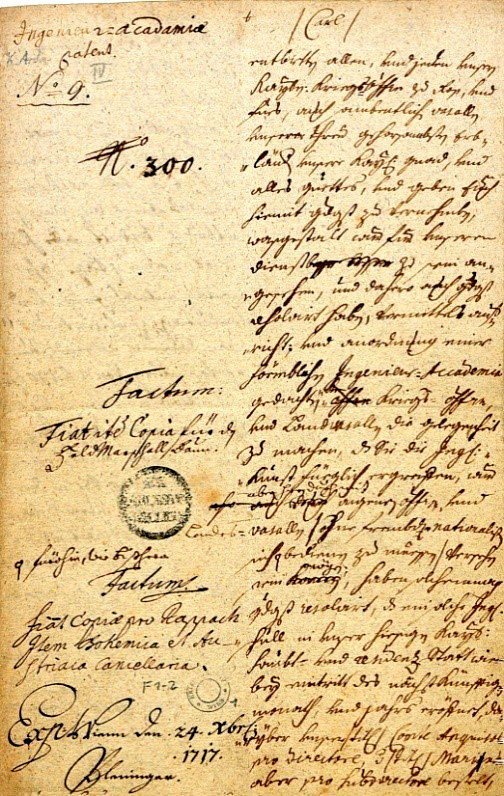

Fig. 2a. Patent of December 24, 1717 for the establishment of an engineering academy in Vienna under the direction of Anguissolas and the deputy director Marinoni (OeStA/KA ZSt HKR SR KzlA IV, 9. [© GZ: ÖSTA-2028656/0012-KA/2017])

Fig. 2b. Emperor Charles VI (1685--1740), painting by Johann Gottfried Auerbach (Museum of Military History, Vienna) (Wikipedia)

With an Imperial patent, dated December 24, 1717, Charles VI -- on recommendation Leander [Leandro] Anguissola (1653--1720) and Marinoni -- set up the first academy for military and civil engineers in the hereditary lands, later also known as the Mathematical and Engineering Academy, and appointed the proponents to be its directors (König 2017, p. 99 f).

Prince Eugene reports to Emperor Charles VI on May 17, 1718 that 45 students, including noble persons, philosophers and artists, were admitted and what progress they had made. Tuition was free, material expenses were low, but the salaries of the directors for part-time work were quite generous.

Marinoni as Cartographer and Court Mathematician

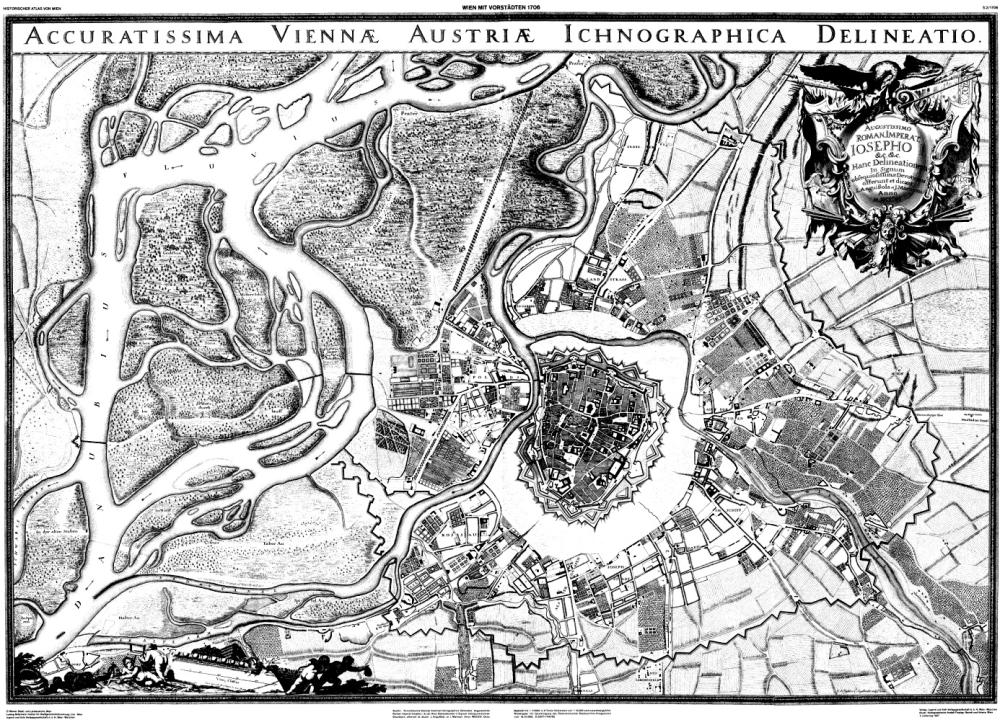

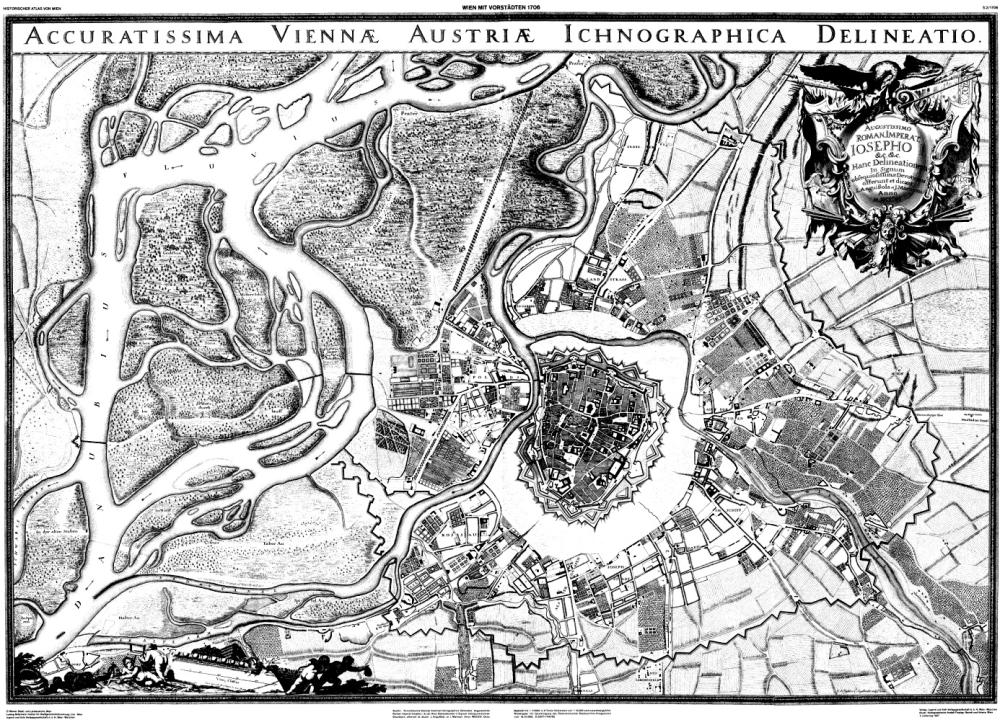

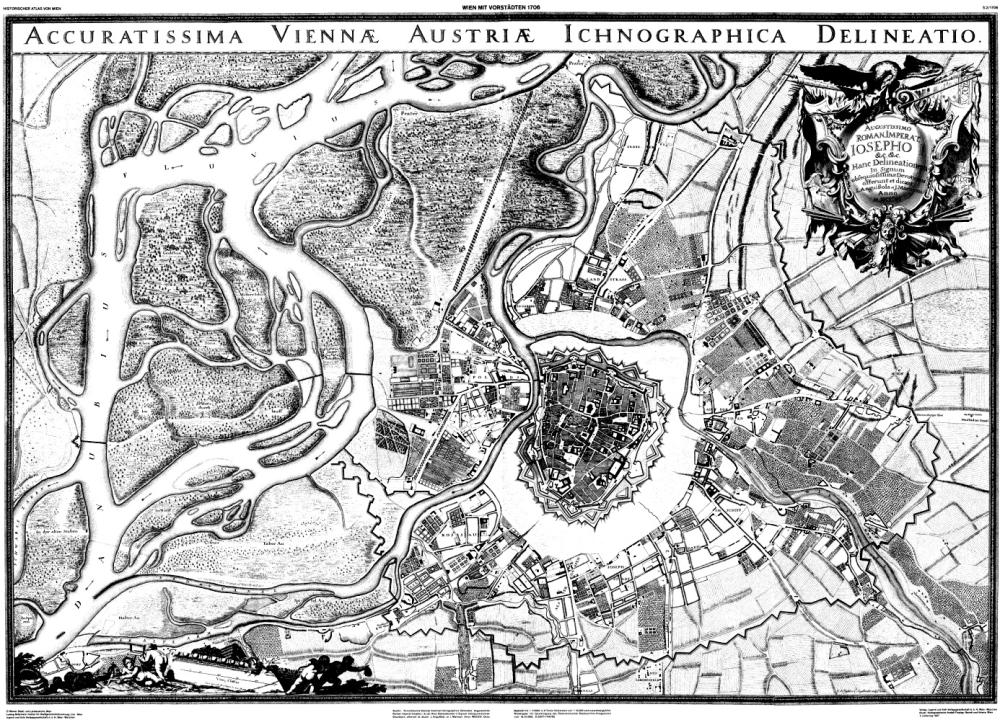

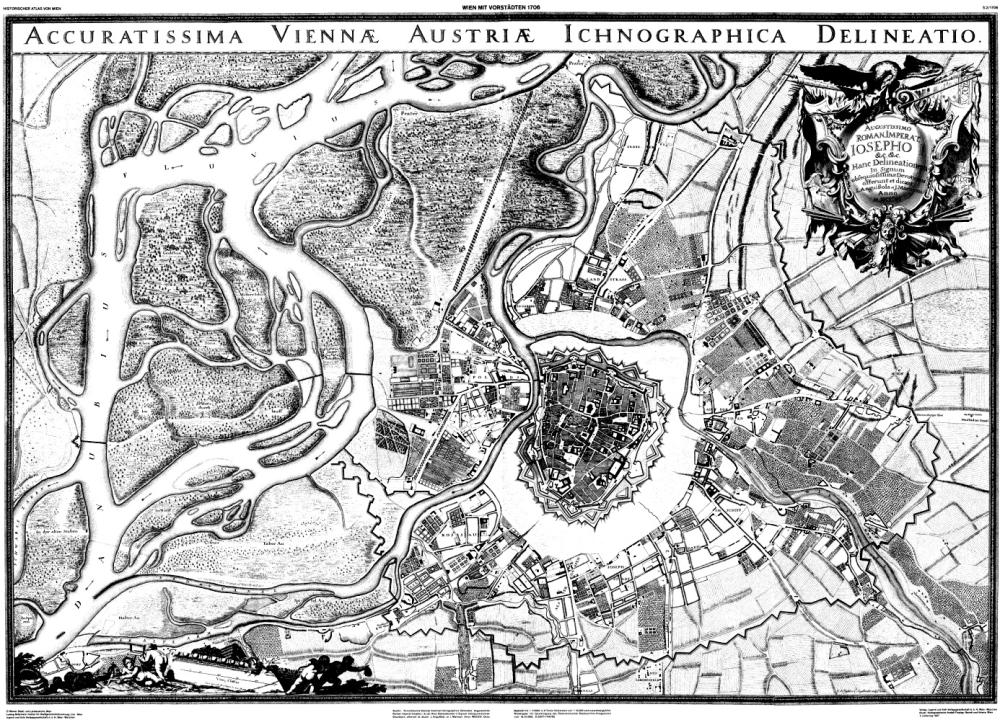

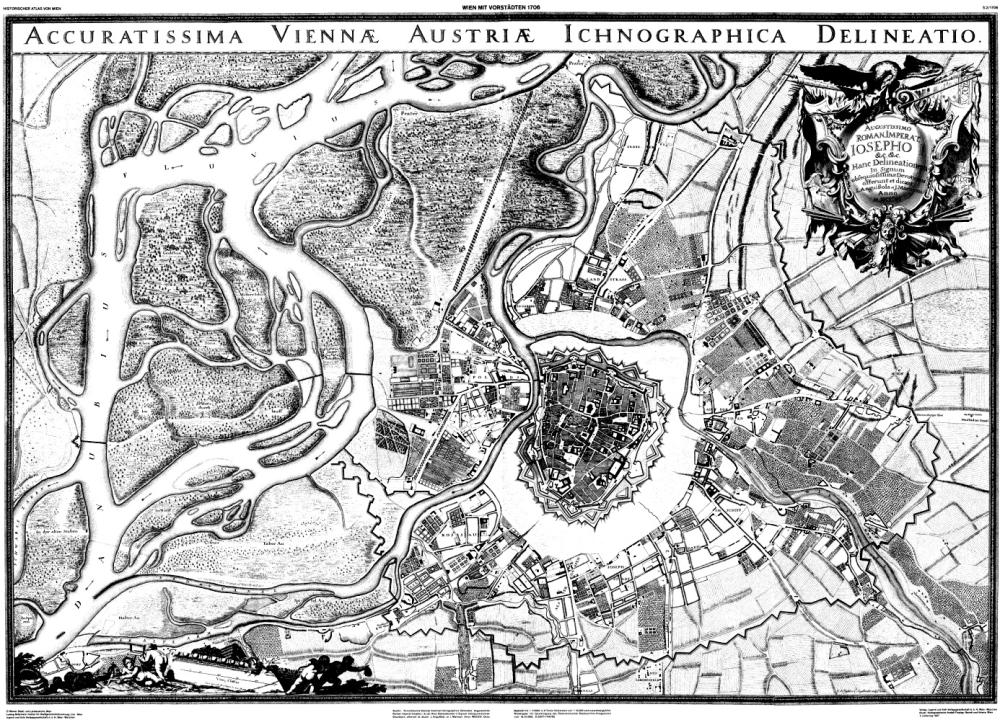

Fig. 3. The map of Vienna (1706) by Anguissola-Marinoni-Hildebrandt-Steinhausen (reprinted 1987) (https://1030wien.at/geschichte/historische-landkarten)

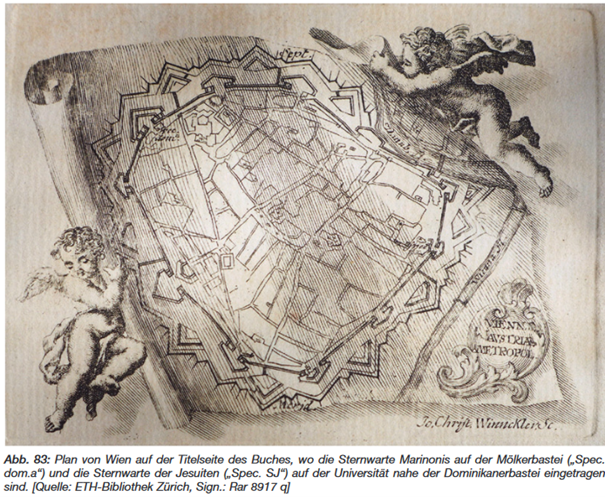

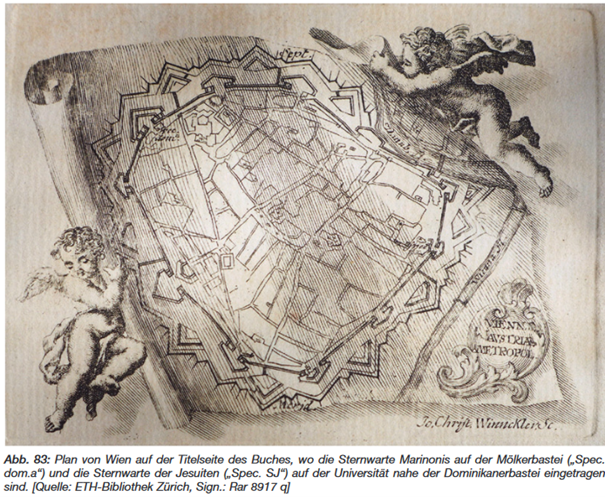

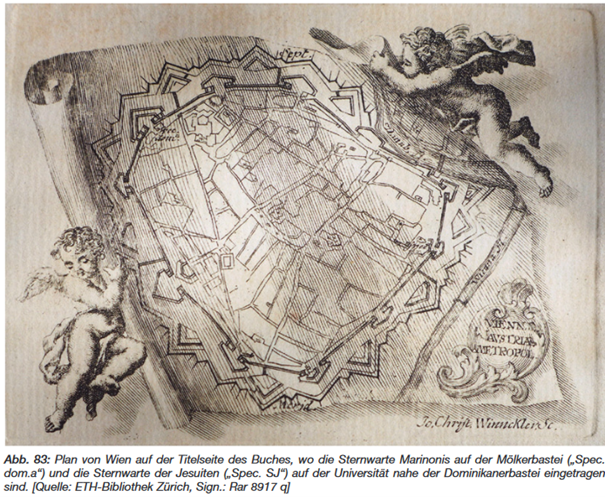

In 1704, Emperor Leopold I commissioned Anguissola and Marinoni to plan the line wall on the outer border of Vienna. In the same year, the famous Anguissola-Marinoni map of Vienna was created with the involvement of the court architect Lukas von Hildebrandt and the city engineer Arnold von Steinhausen (copper engraving 1706, reprint 1710), on which the fortifications are drawn. The inclusion of the suburbs in the truce and jurisdiction of the Imperial Capital and Residence City of Vienna by decree of July 15, 1689 resulted in the need for a city plan of the new, larger Vienna.

Marinoni is justifiably proud of the quality of its map renderings. The 300-year-old Milan cadastre (1719--1729, 16 large map sheets at a scale of 1:72,000) is the first cadastre to be drawn up based on the survey of an entire, contiguous country. In 1777, a copper-engraved map consisting of 9 sheets, reduced to a scale of 1:90,000, was created in Milan ("Carta Topografica dello Stato di Milano seconda la Misura Censuaria"). Marinoni is regarded as a model for the cadastral surveys of the 19th century.

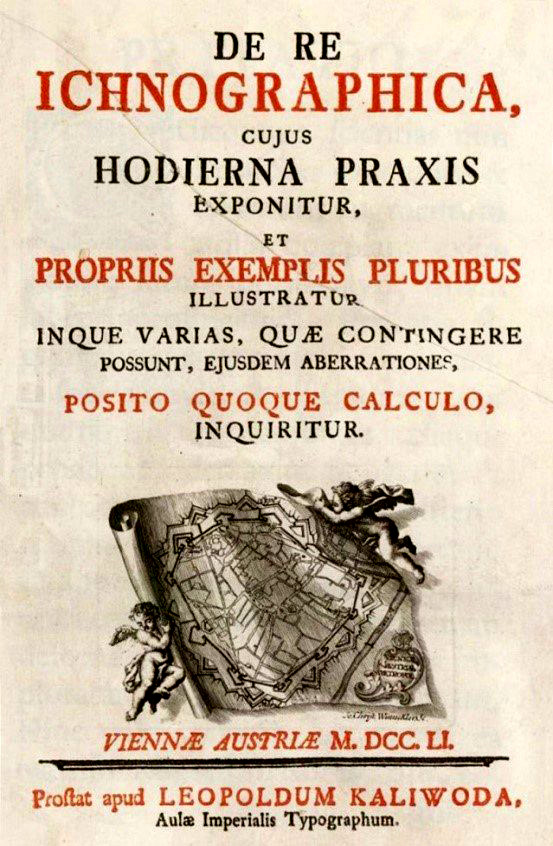

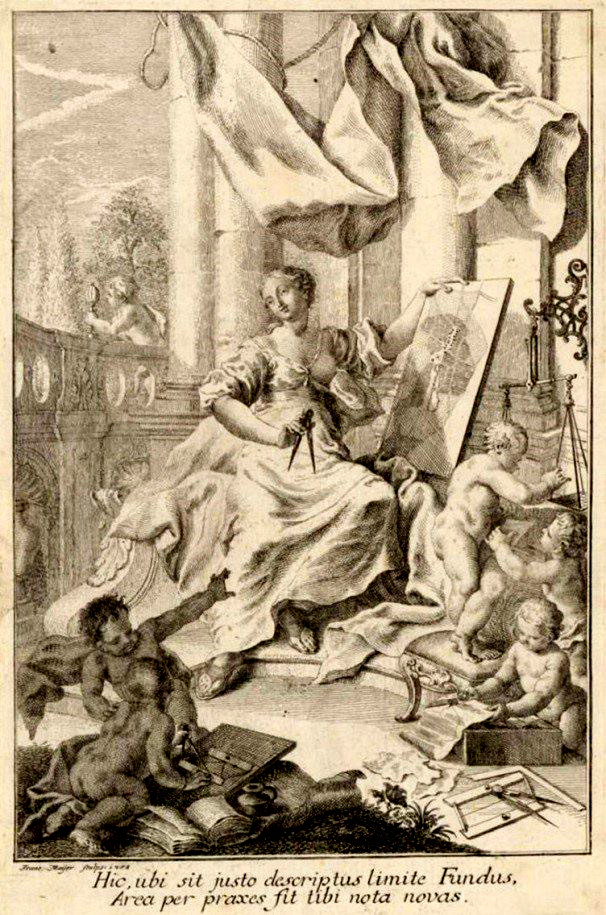

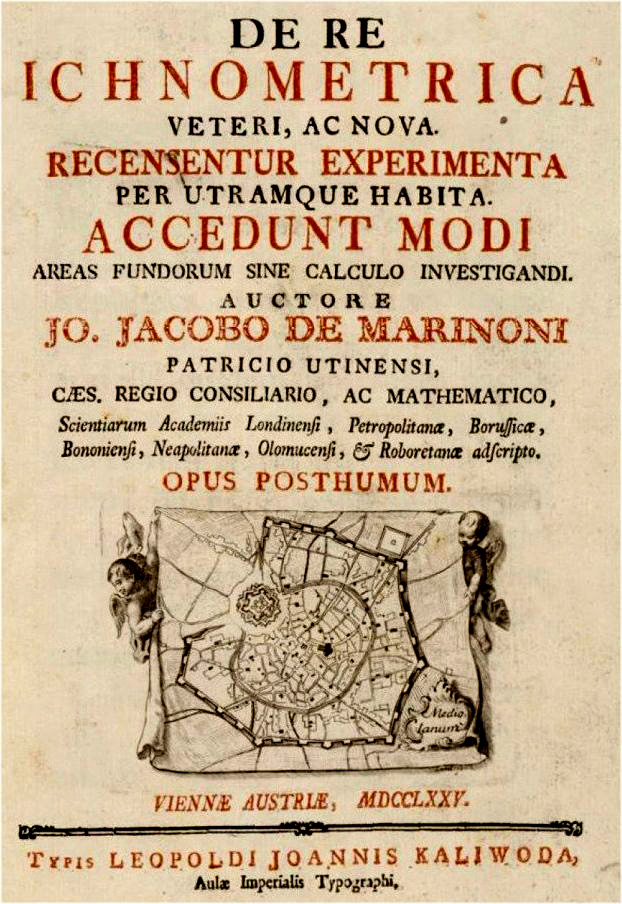

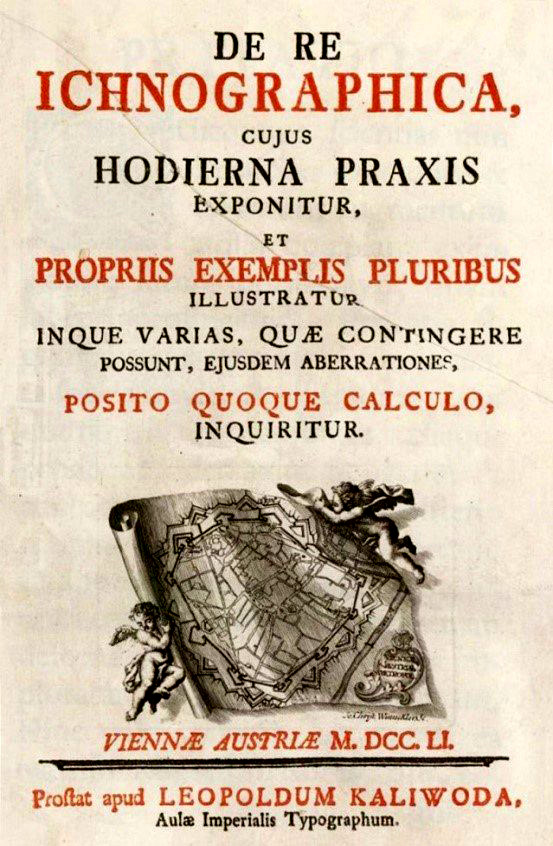

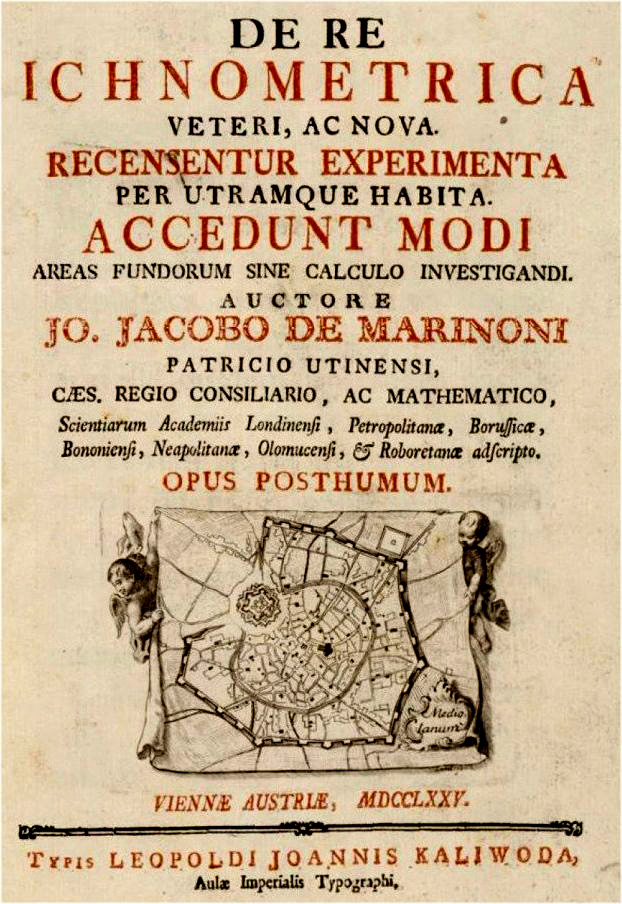

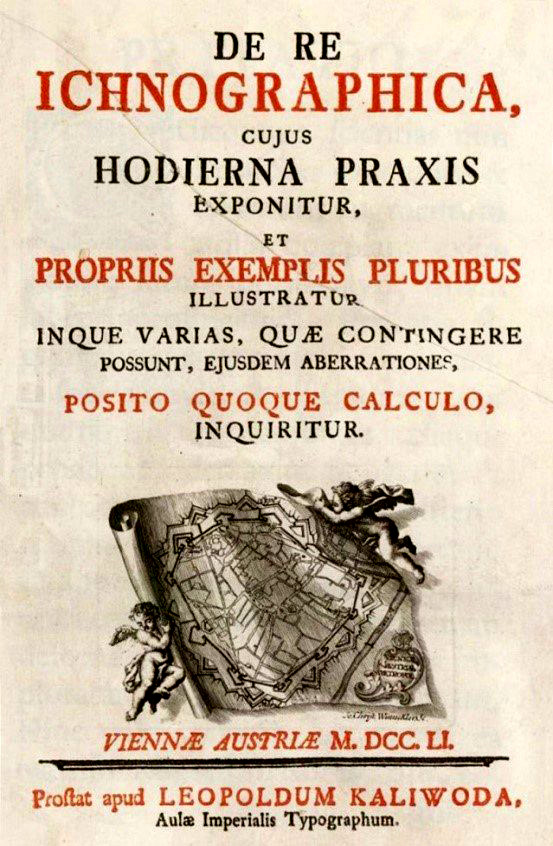

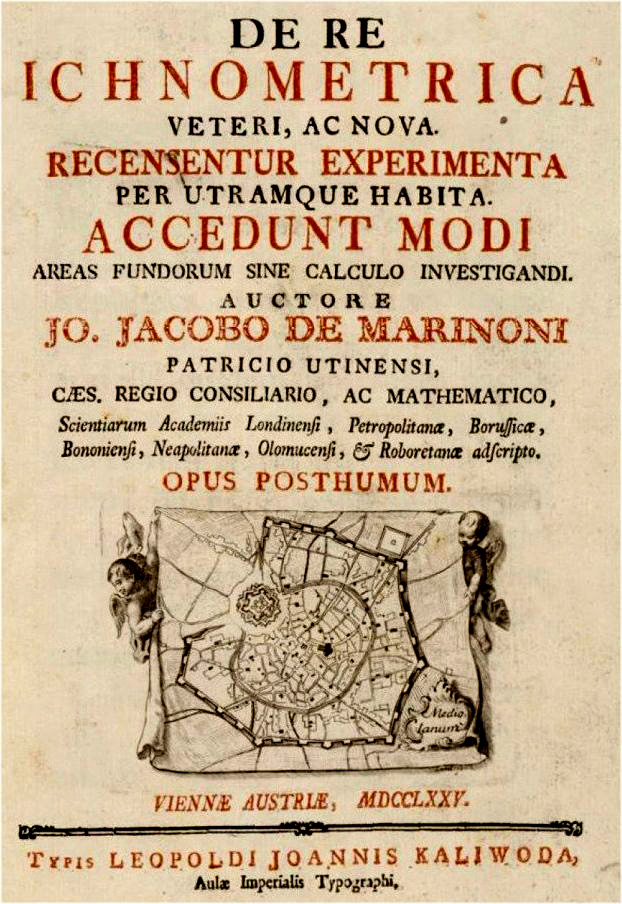

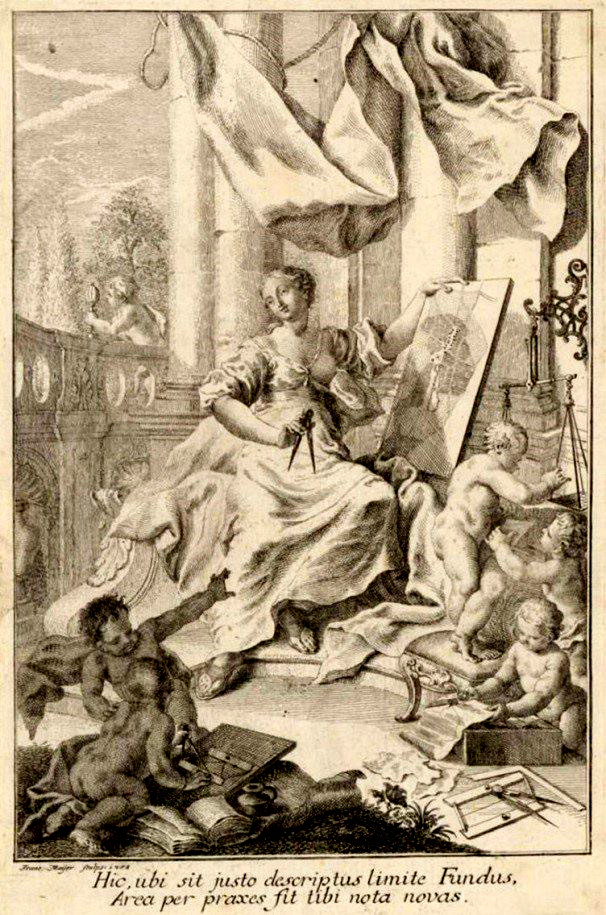

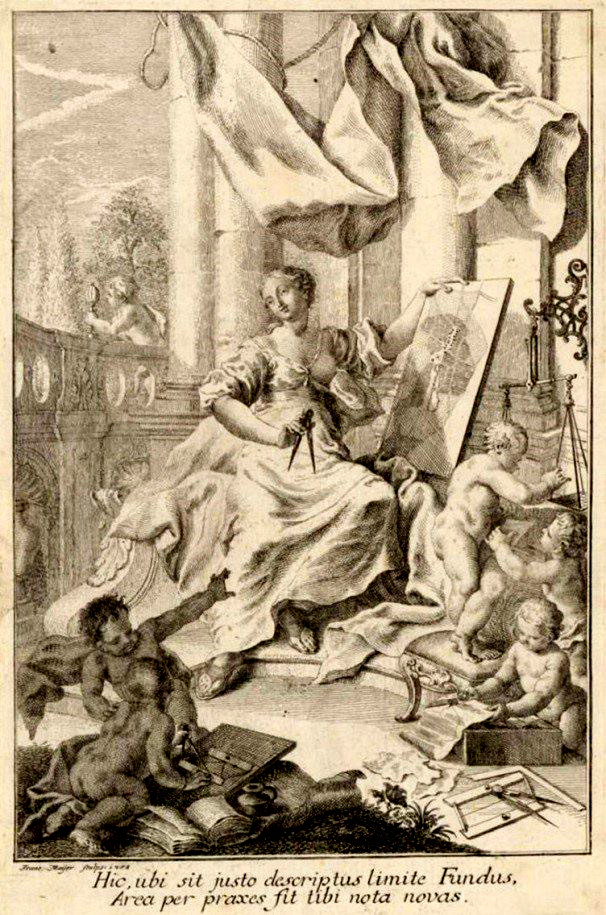

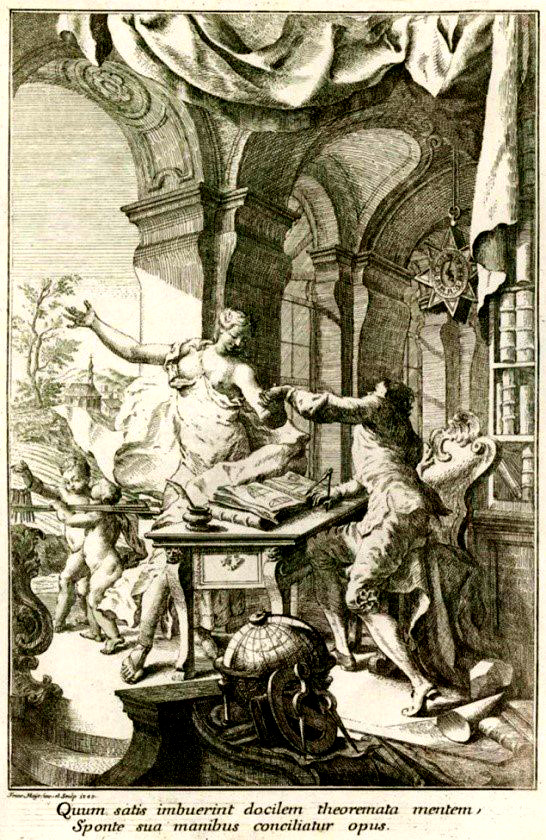

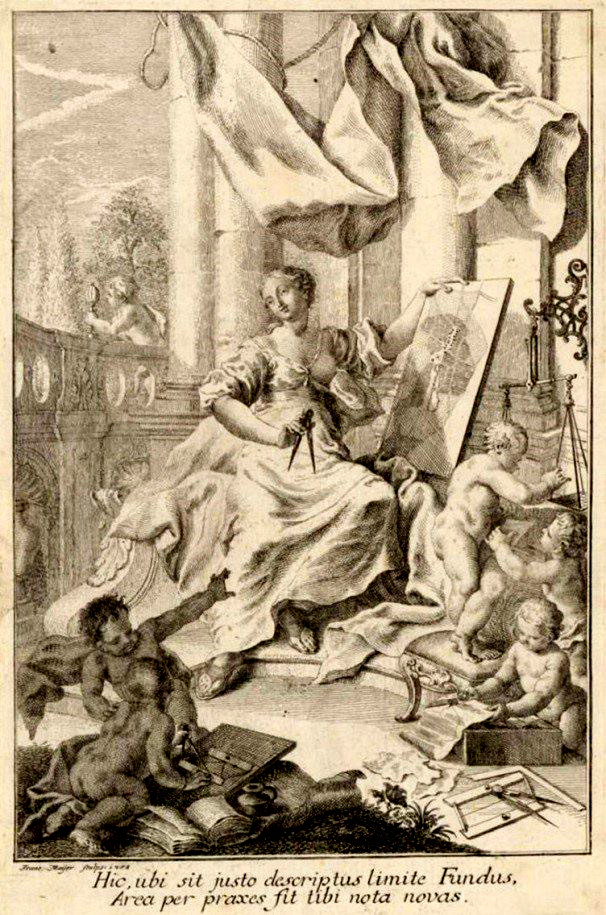

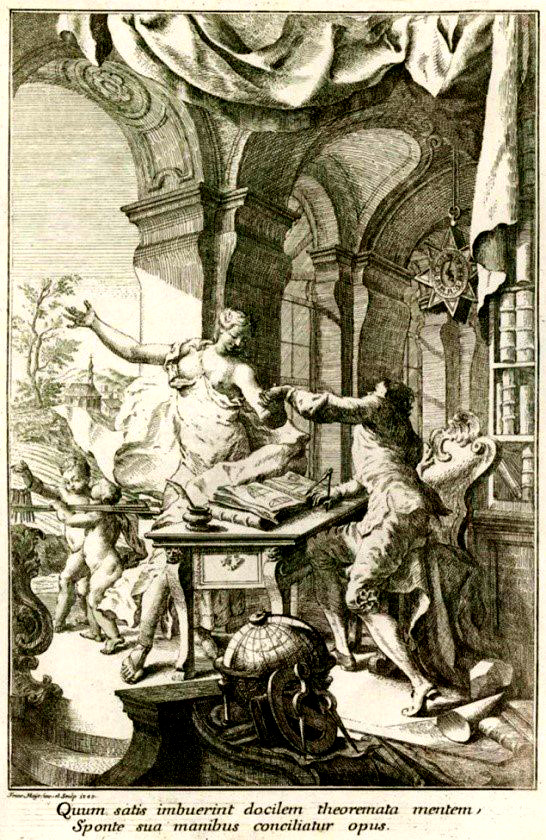

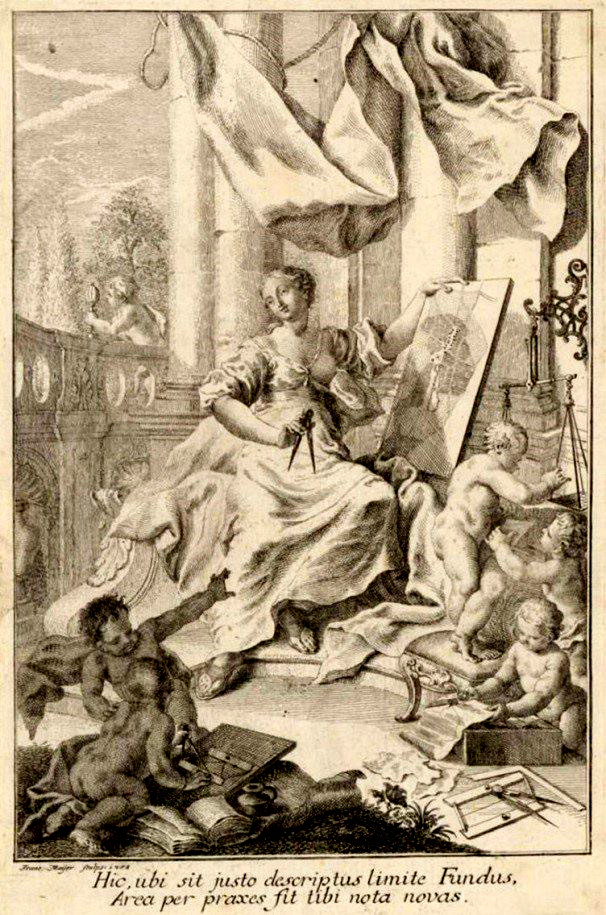

Many of the maps and plans, which Marinoni created under the auspices of the Austrian Imperial family, have survived, and they not only represent a technical masterpiece, but are also priceless cultural assets of unsurpassed beauty. His two masterworks, describing his surveying activites, are "De re ichnographica" (Vienna 1751, Making maps and plans) and "De re ichnometrica" (Vienna 1775, The Surveying Technology).

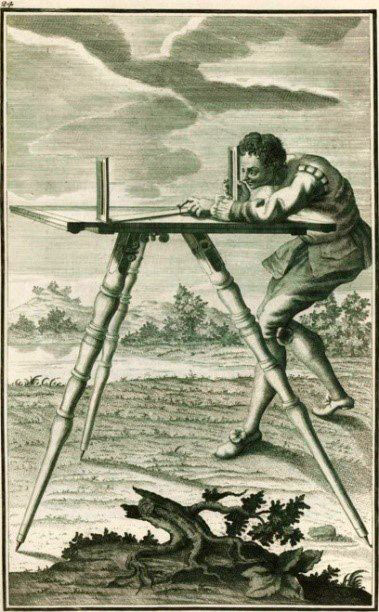

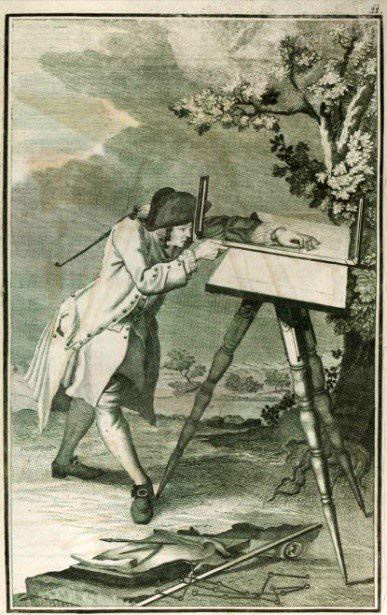

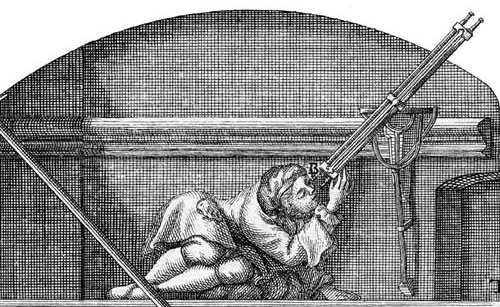

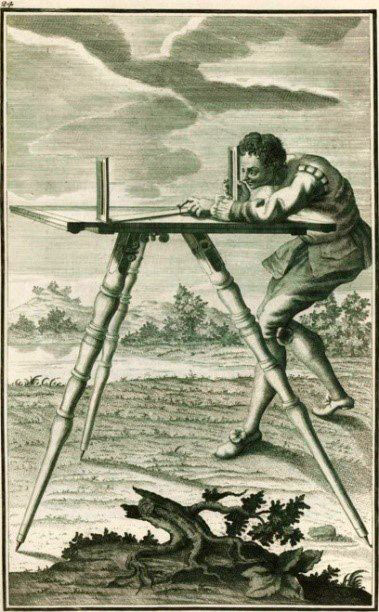

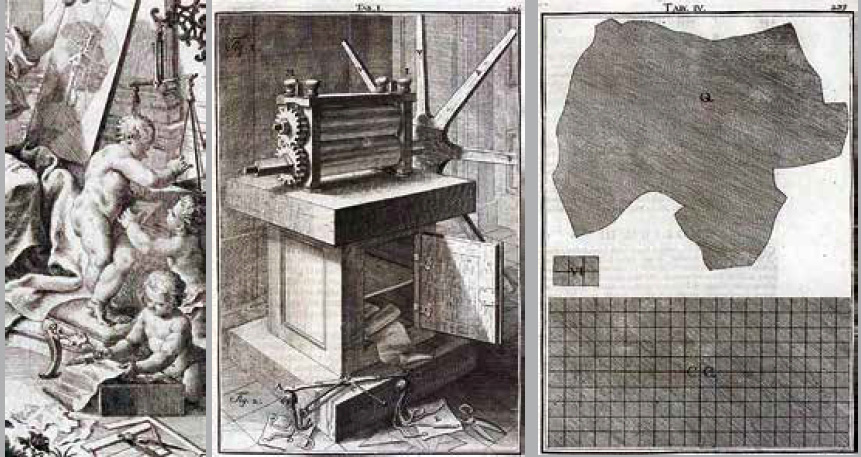

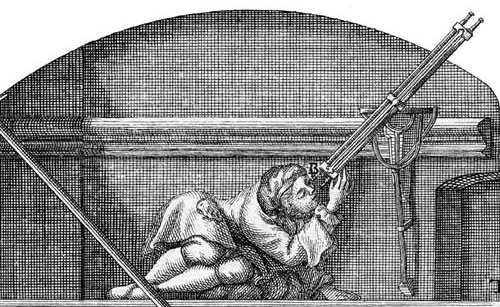

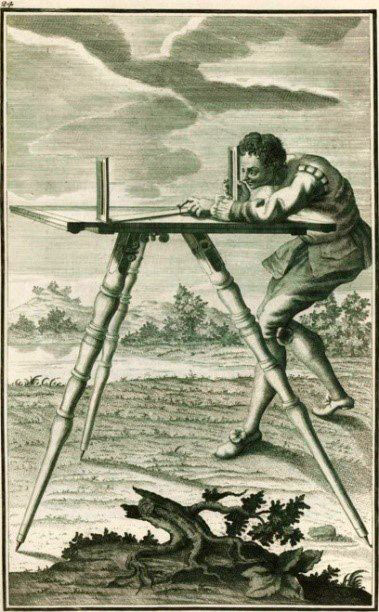

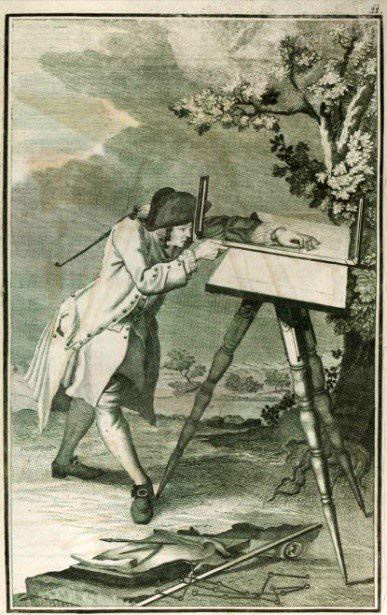

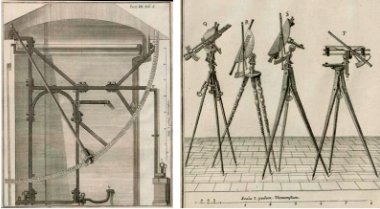

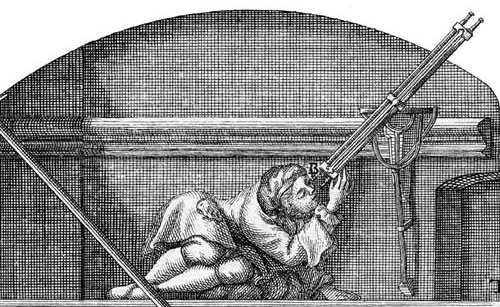

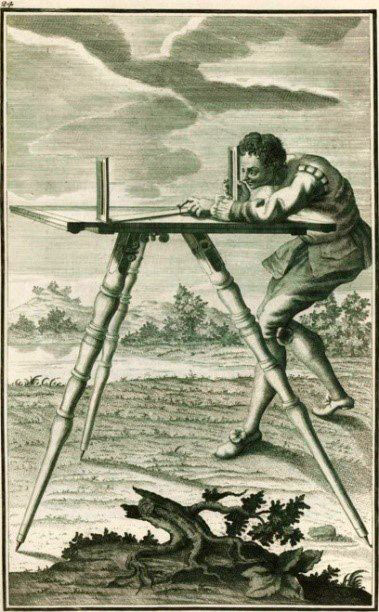

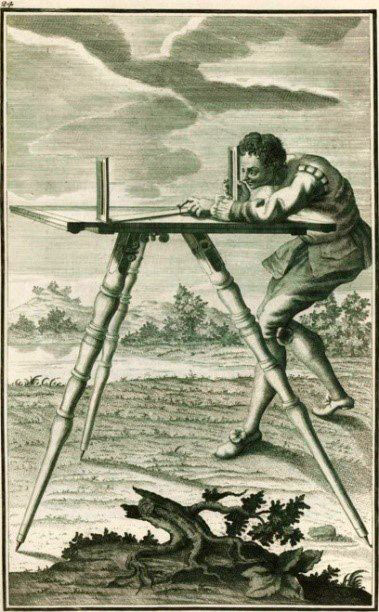

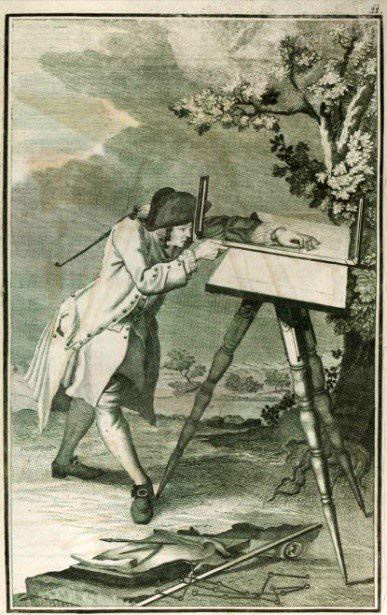

Fig. 4a. Measuring table, invented by Johannes Prätorius [Johann Richter] (1537--1616), improved by Marinoni ("De re ichnographica" (1751), Graphic 24, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 771 q)

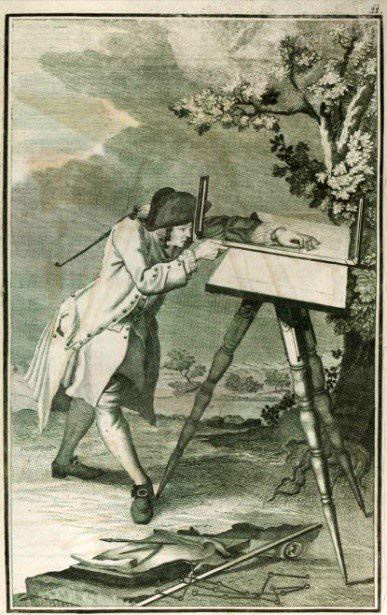

Fig. 4b. Measuring table, invented by Johannes Prätorius [Johann Richter] (1537--1616), improved by Marinoni ("De re ichnographica" (1751), Graphic 11, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 771 q)

When surveying Vienna, Marinoni used the measuring table, invented by Johannes Prätorius [Johann Richter] (1537--1616), professor of the Nuremberg University in Altdorf. But Marinoni had improved it by fitting a larger table on the top and he used a more stable tripod. Since then, he has used this new measuring table regularly and made constant efforts to perfect it. Finally, in 1714, he constructed the final version with which he carried out the cadastral survey of Milan. His improvements to the measuring table, consisted in enlarging the diopter ruler and also attaching a mountain diopter to it for strongly inclined sights, and he also designed a circular and a linear displacement option for the table top in two mutually perpendicular directions in order to be able to precisely adjust the measuring table over the position.

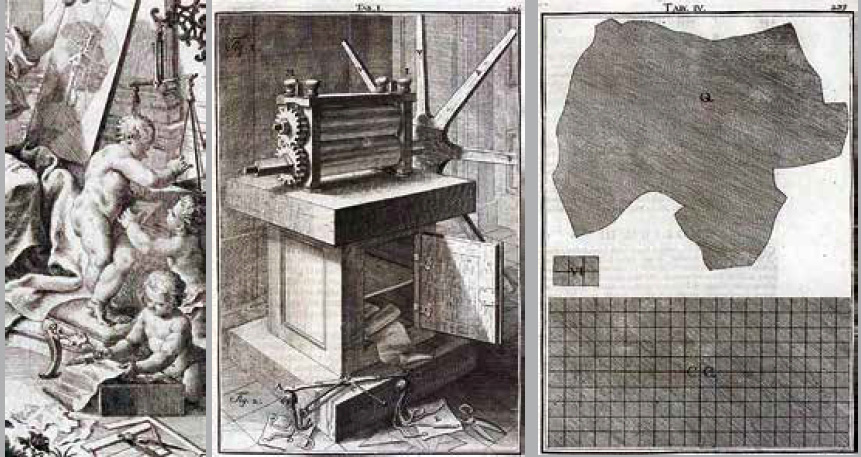

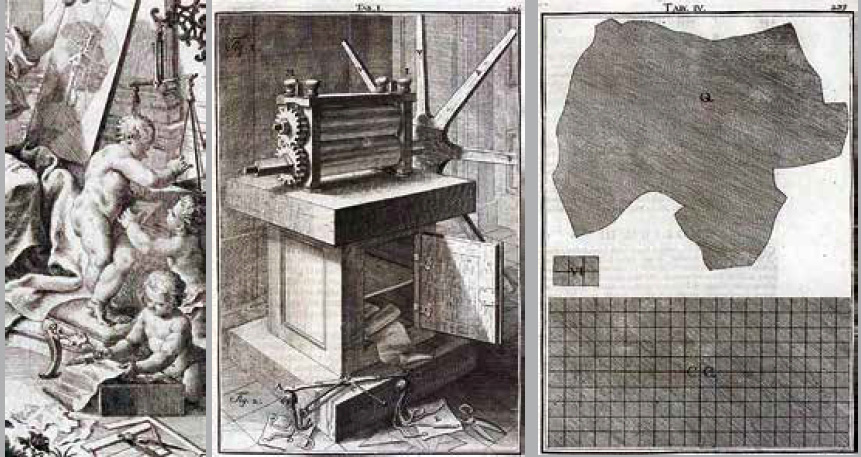

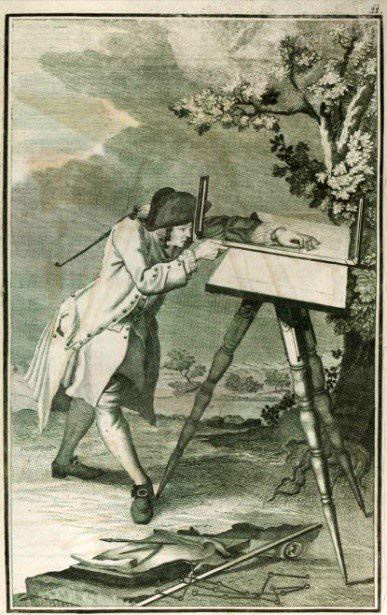

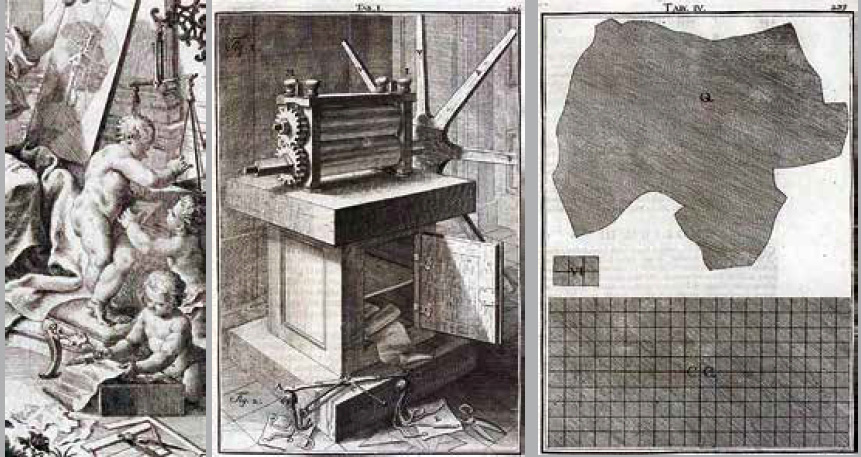

Fig. 4c. Application of the Planimetric Balance for area determination and production of standardized foils (Marinoni: "De re ichnometrica" (1775), frontispice, Tab. I, p. 231, Tab. IV, p. 239, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 1072 q)

Marinoni as Astronomer

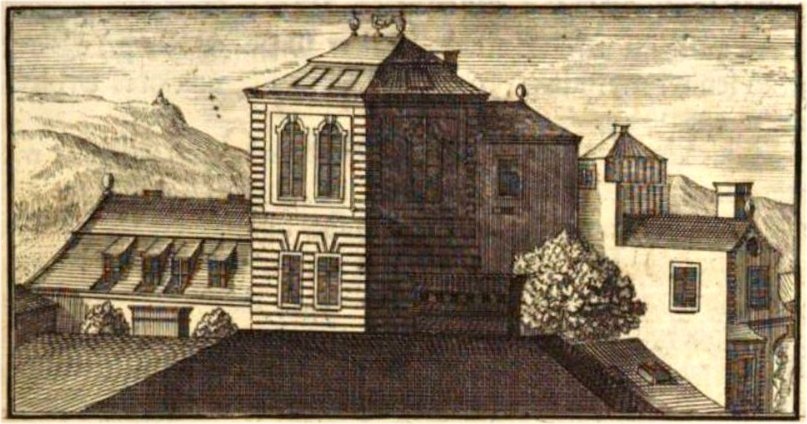

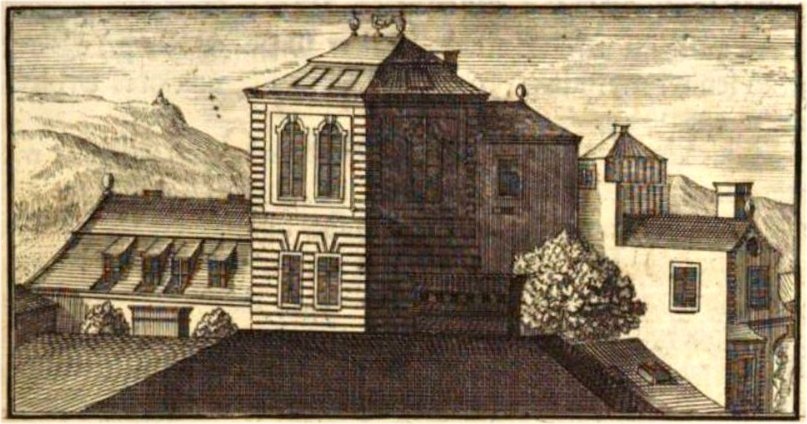

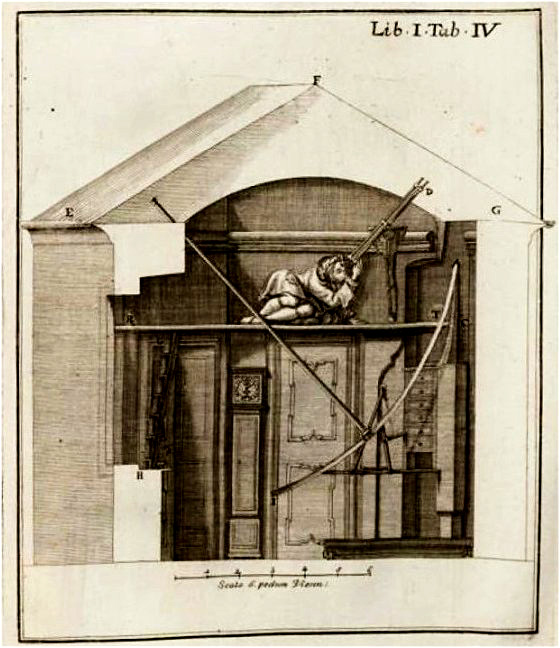

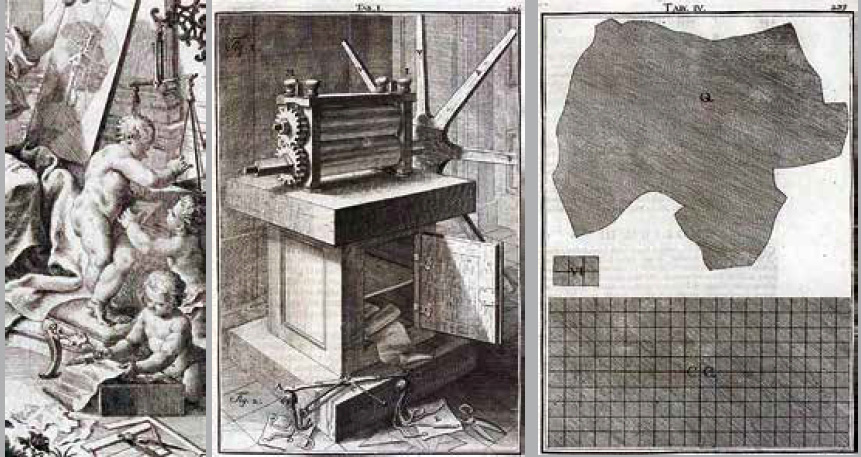

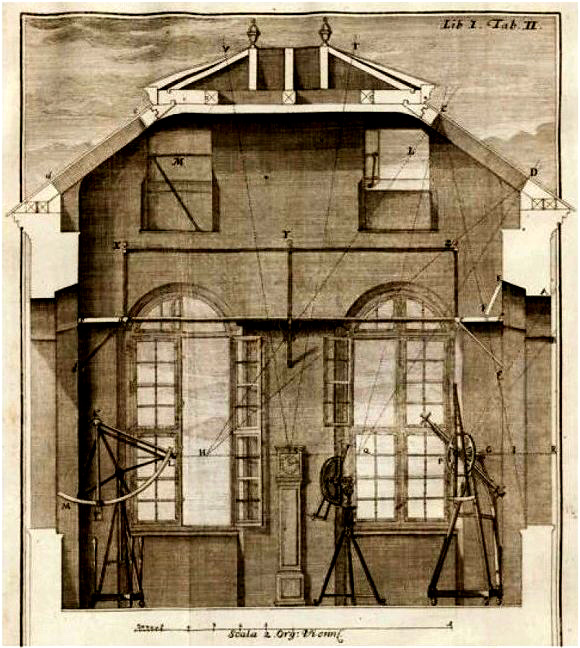

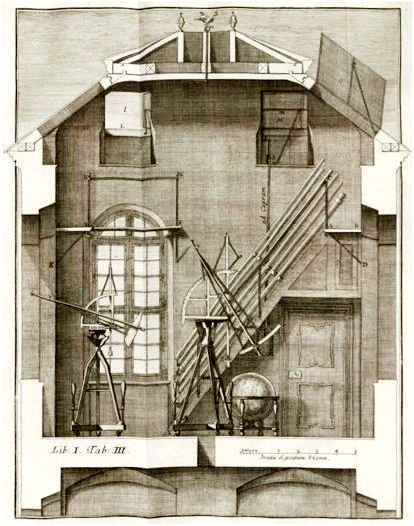

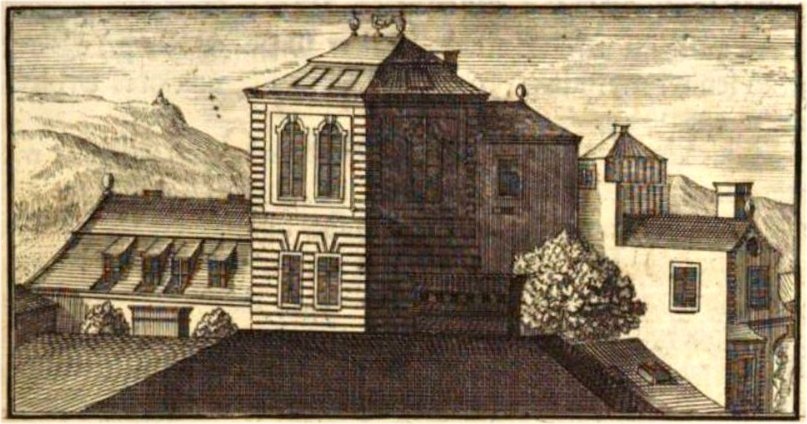

Fig. 5a. The house of the court mathematician Marinoni on the Mölkerbastei with the astronomical observation tower (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, p. 1, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

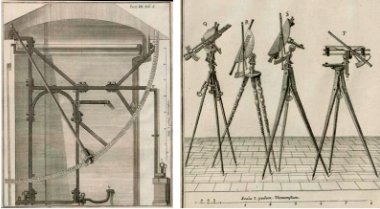

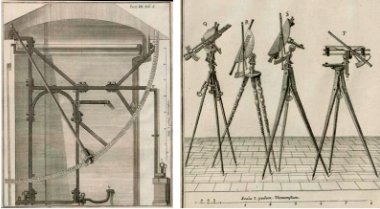

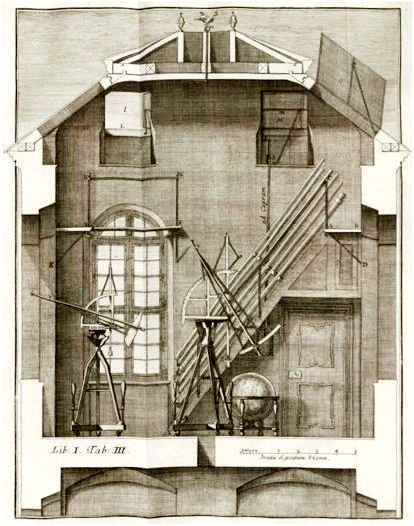

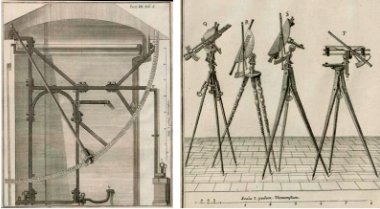

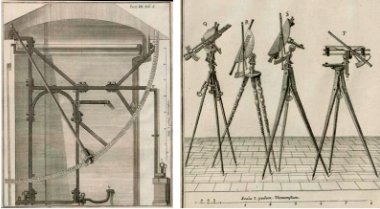

Fig. 5b. Some of Marinoni’s astronomical instruments (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

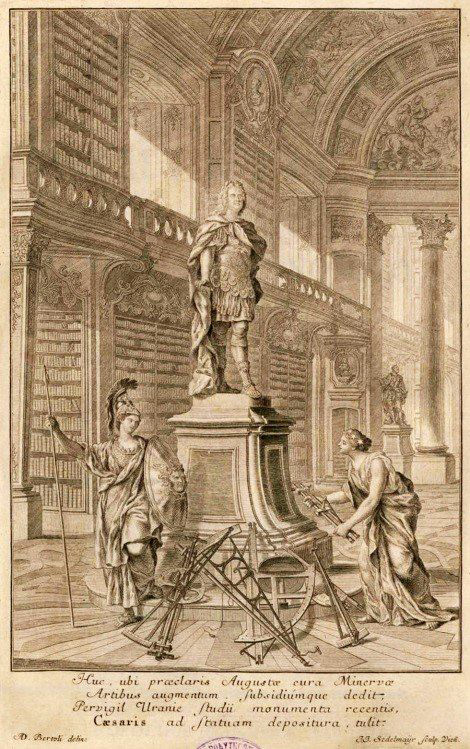

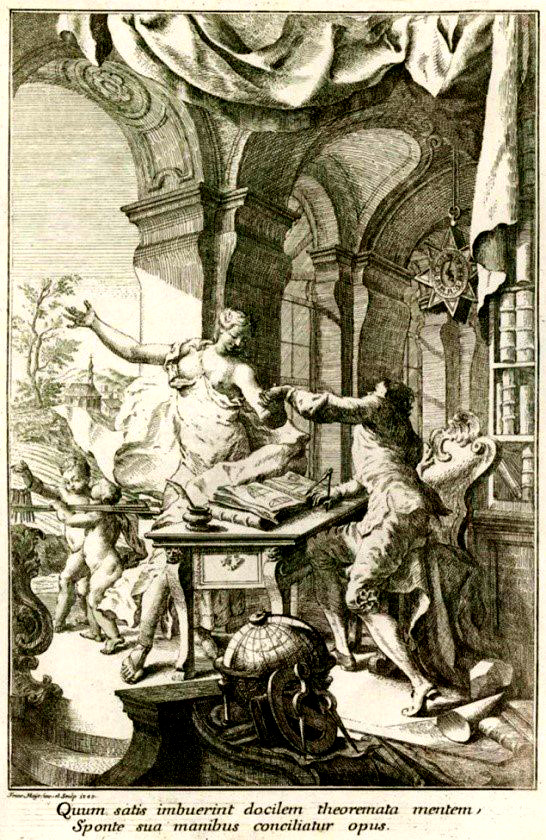

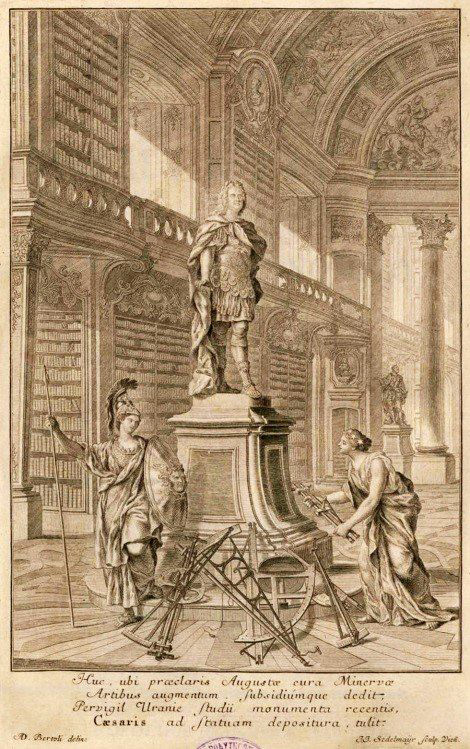

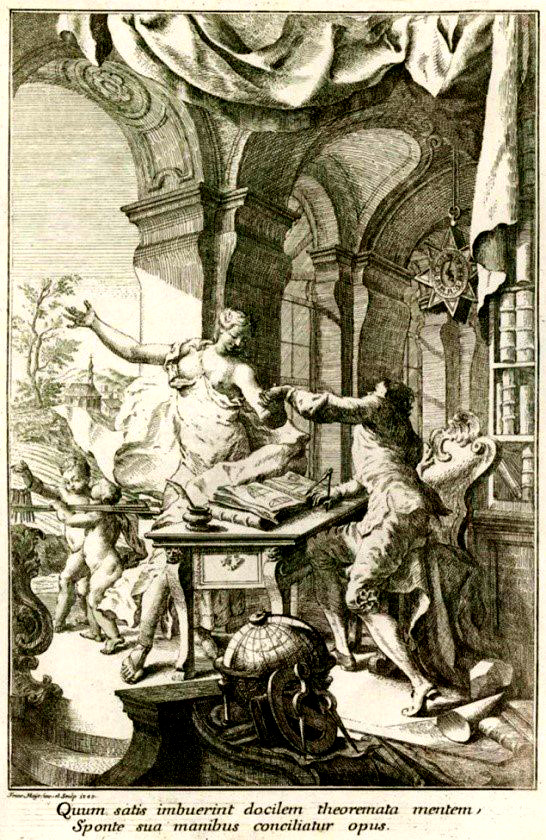

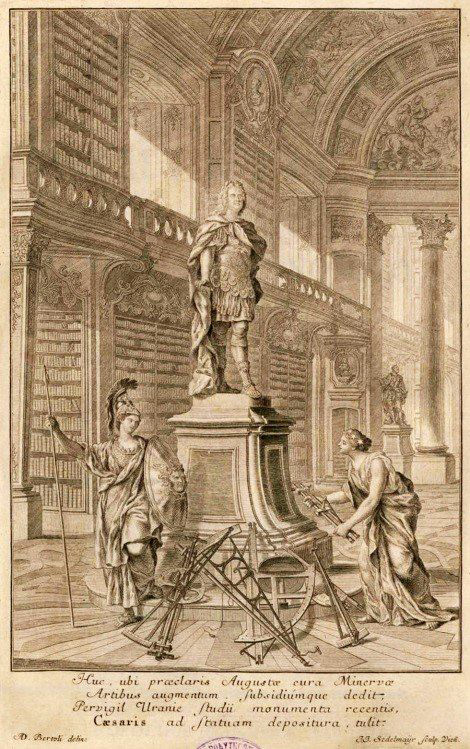

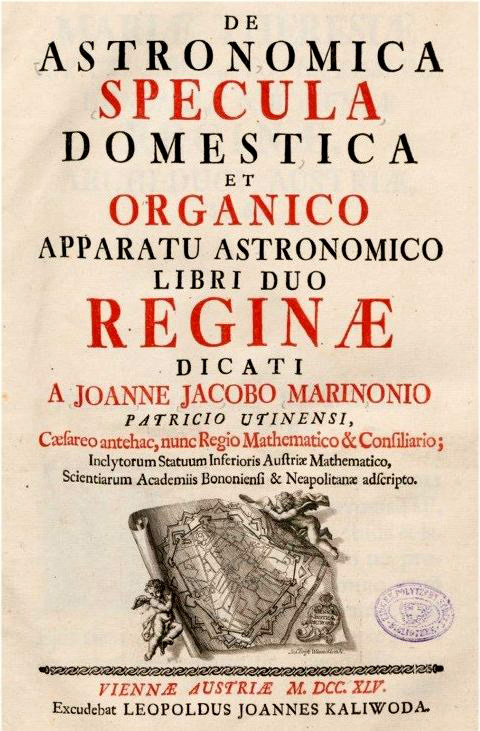

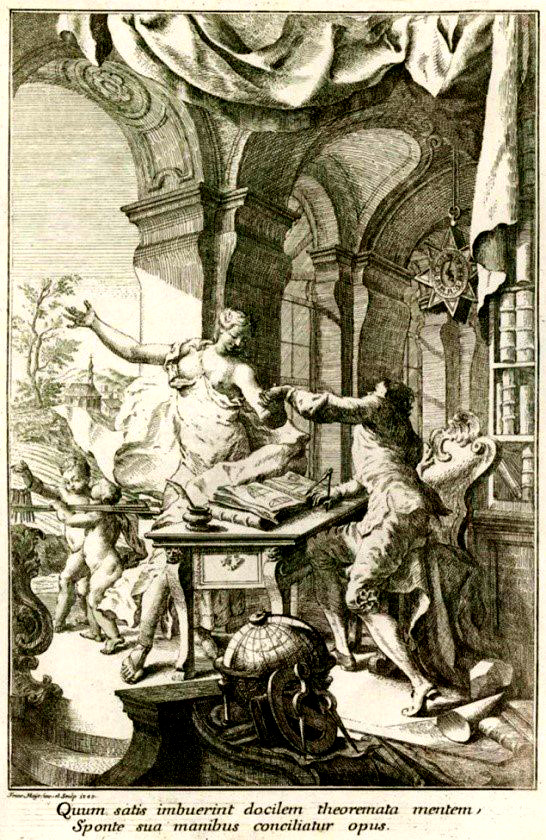

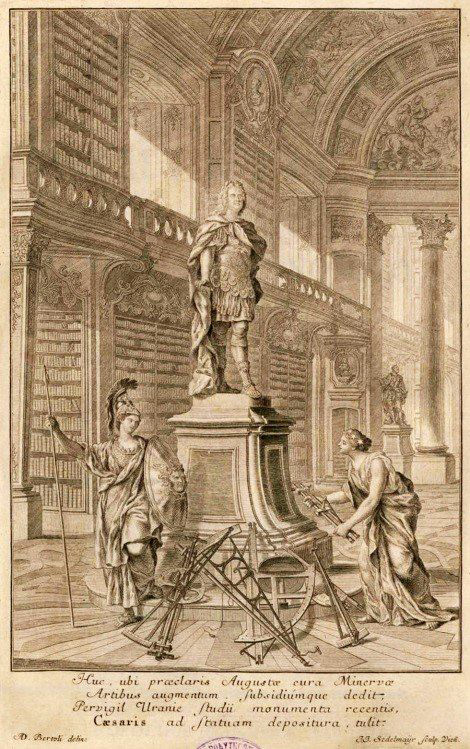

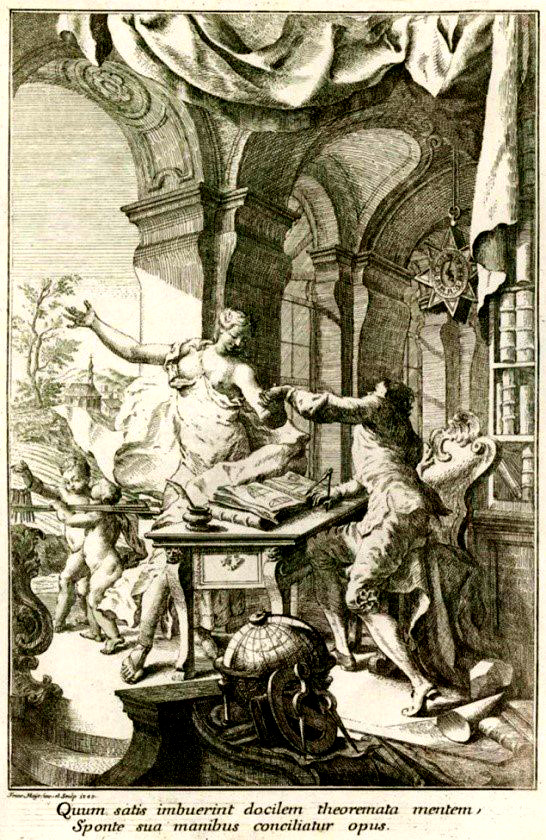

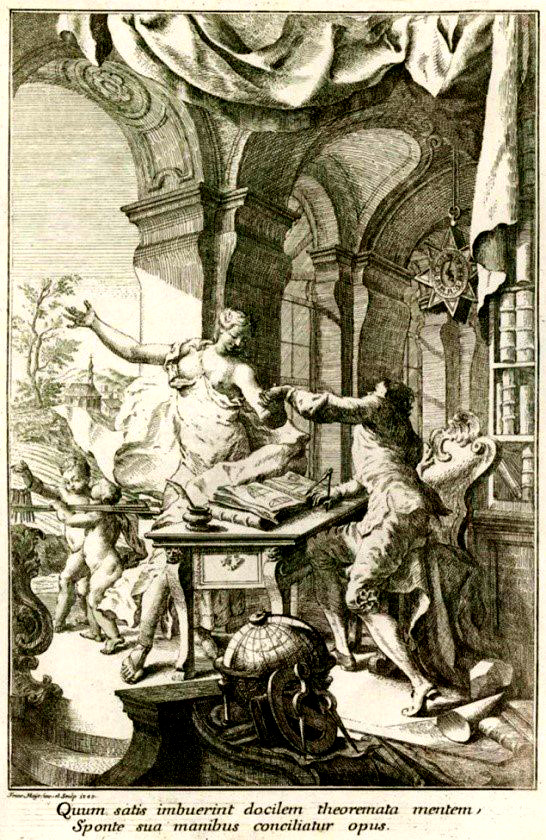

Fig. 5c. Frontispice of Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745 (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Marinoni had the first observatory in Vienna set up in his private home on the Mölkerbastei in the 1720s, for which he had the most modern observation instruments, purchased at the Emperor’s expense, as he wrote in 1745 in his book De astronomica specula domestica et organico apparatu astronomico libri duo Reginae dicati a Joanne Jacobo Marinonio patricio utinensi, etc. described. In the dedication of De astronomica specula to Maria Theresa, Marinoni first praises the generous support of her late father Charles VI. for its observatory.

Due to the heights of the Vienna Woods (Wiener Wald), the Marinonis Observatory only had lack of horizon view, with the result that rising and setting points of the celestial bodies were often not precisely ascertainable, and there was also fog from the Danube lowlands.

The house is also rotated 45° from the meridian. Marinoni therefore concentrated on positional and transit astronomy, observations of the corresponding altitudes in order to precisely determine the meridian, culmination observations and tracking the Jupiter satellites.

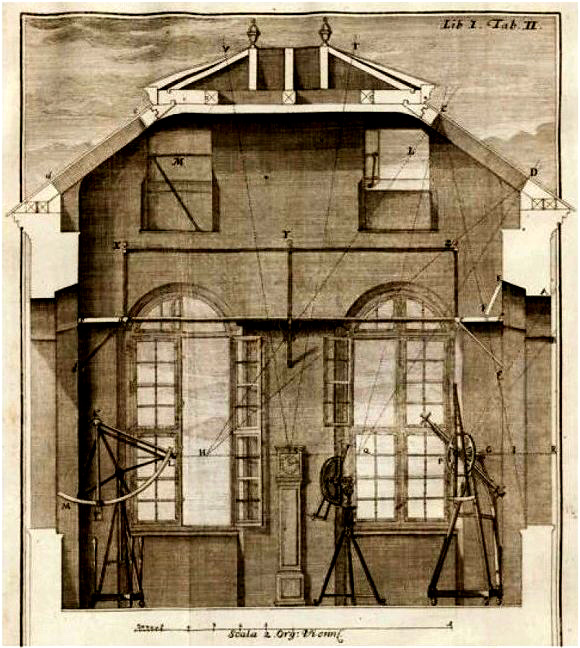

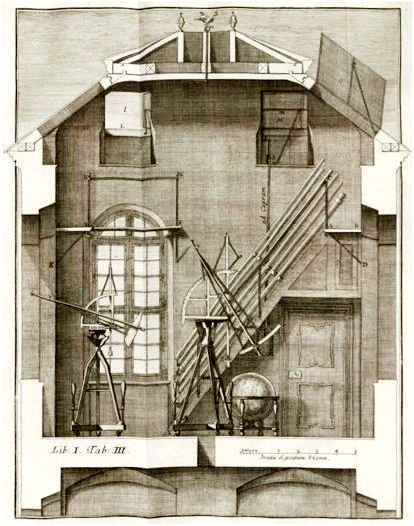

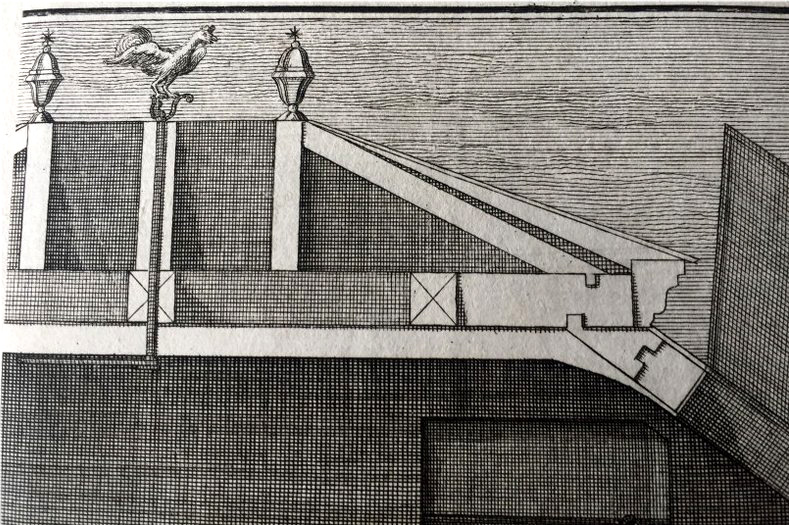

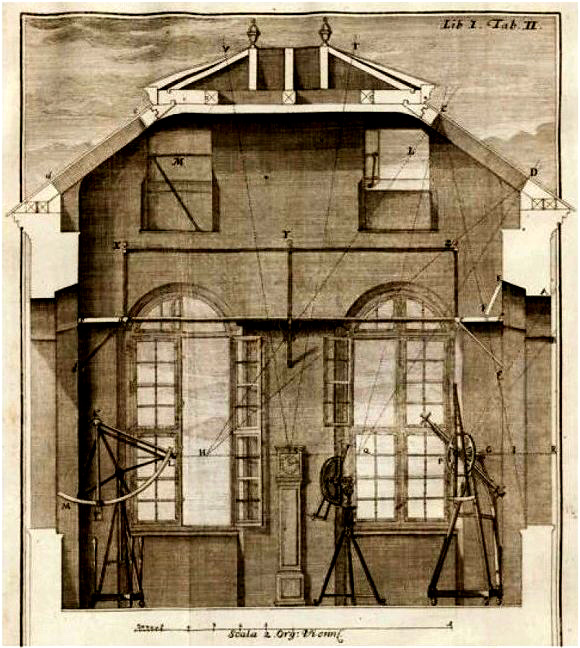

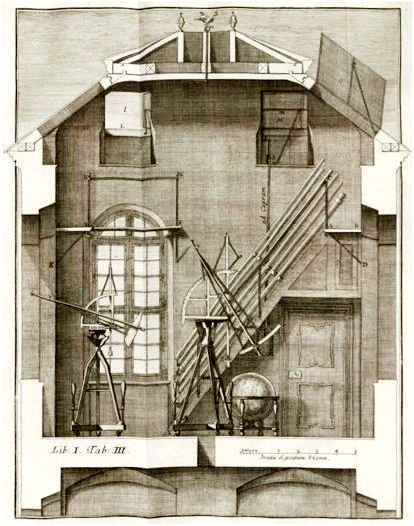

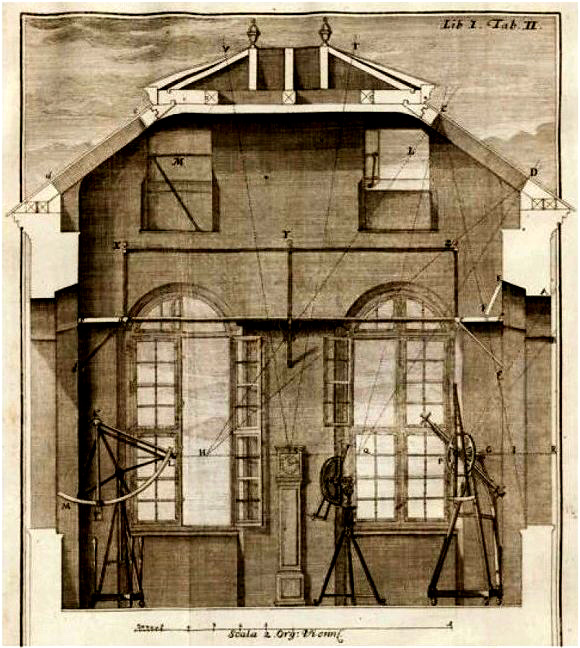

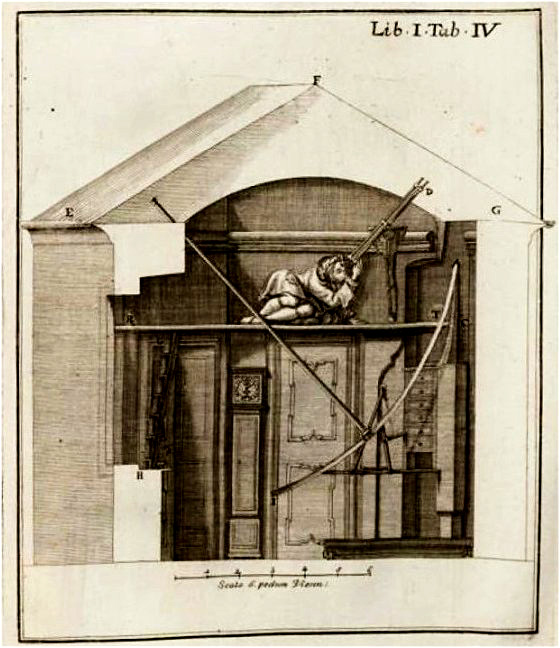

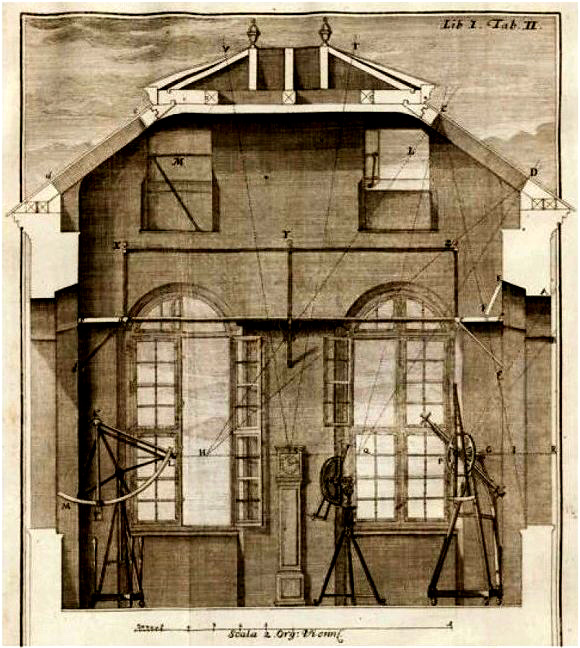

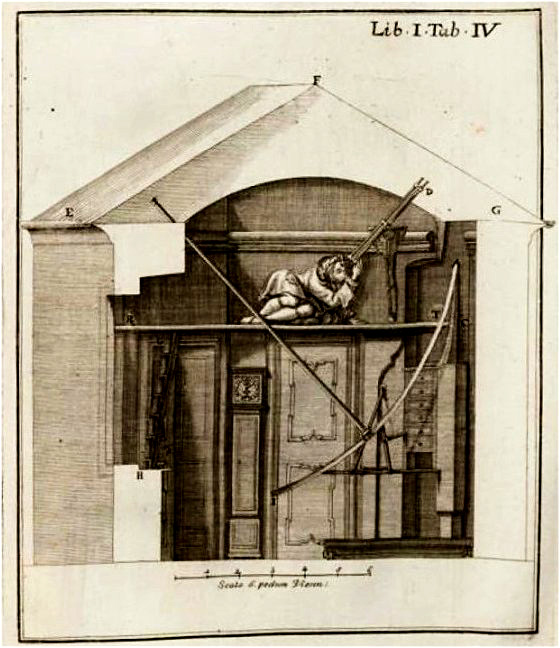

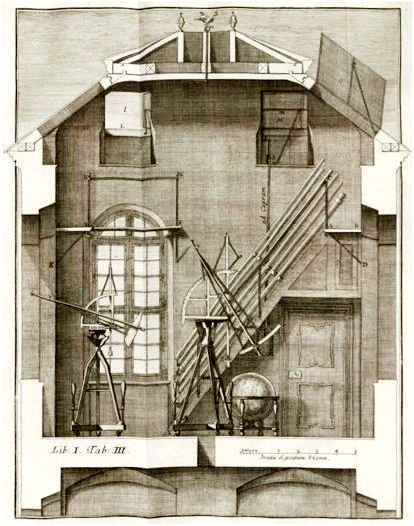

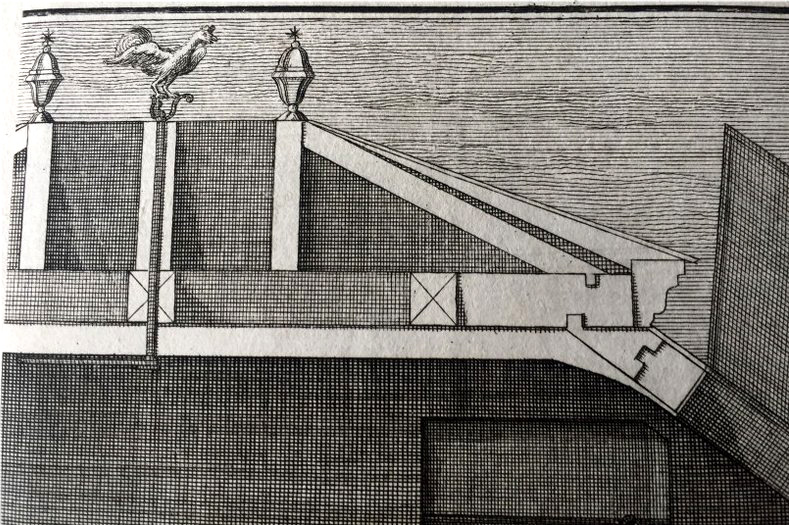

In the description of his observatory in "De astronomica specula domestica", sections of the building illustrate the high windows, the wooden roof beams, the narrow gallery with the iron handrail and the observation pendulum clock.

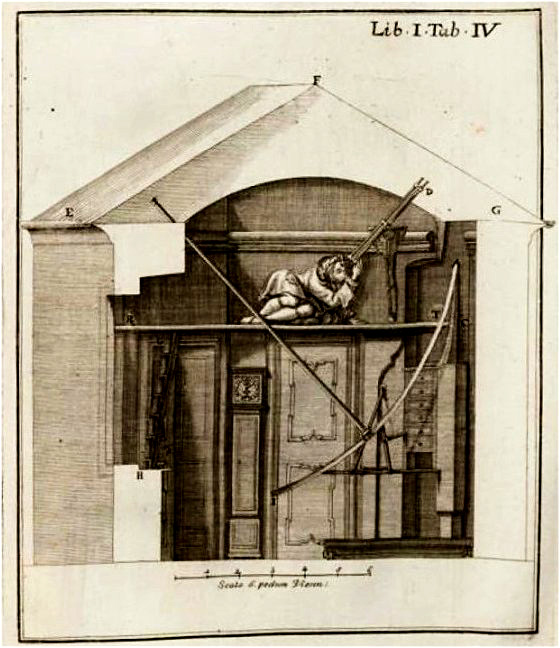

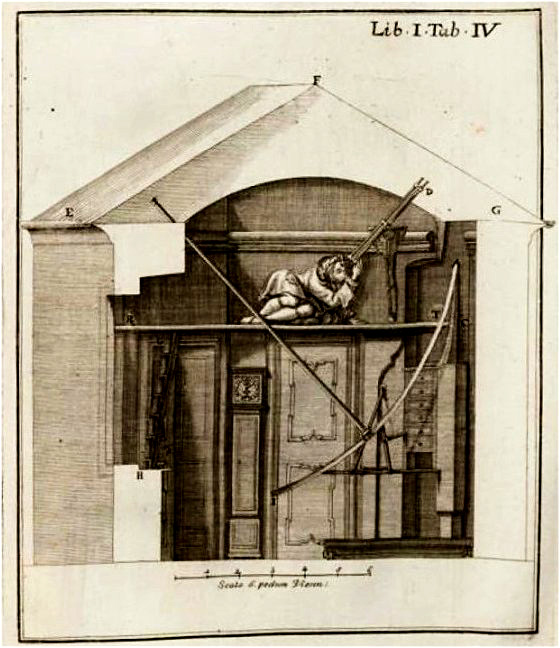

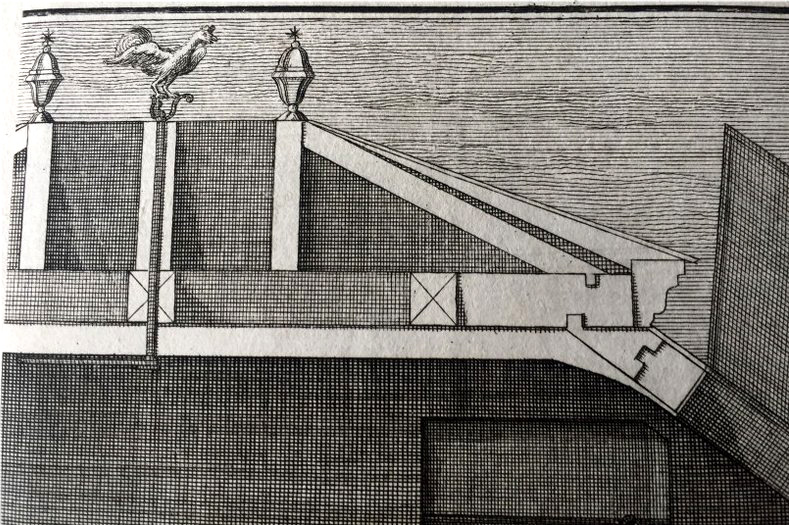

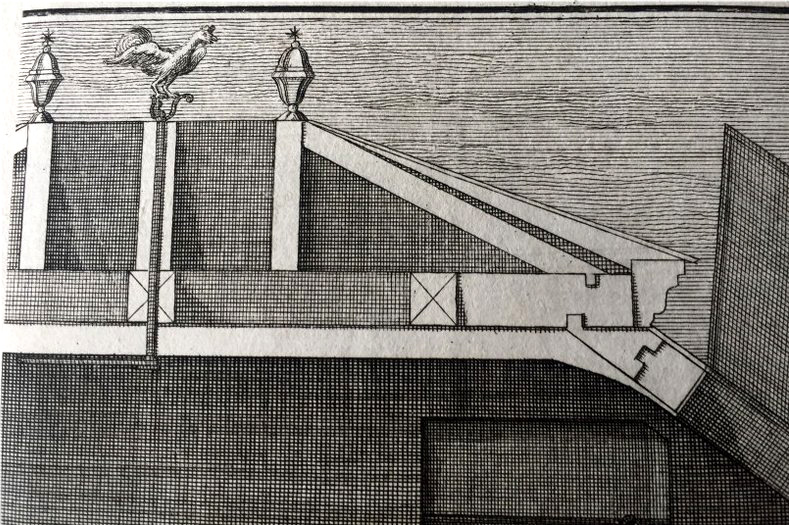

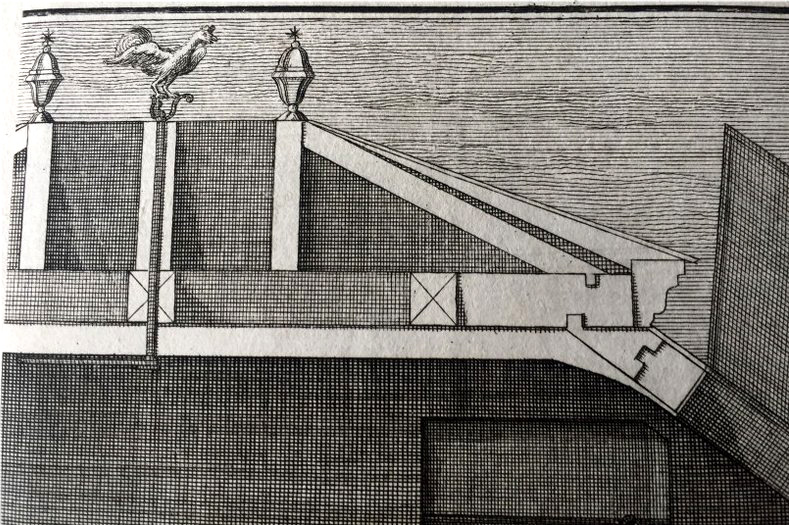

On the roof of the astronomical tower, there was a weather vane in the form of a rooster, which was also Marinoni’s heraldic animal, connected by a vertical shaft to a pointer that showed the wind direction on a compass rose on the ceiling of the main room of the observatory, which could be read without having to go outside.

Fig. 6a. Astronomical observation tower on Marinoni’s house on the Mölkerbastei, with astronomical instruments (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, Tab. II (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 6b. Astronomical observation tower on Marinoni’s house on the Mölkerbastei, with astronomical instruments, with a weather vane (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, Tab. IV (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 6c. Marinoni’s Observatory on the Mölkerbastei with a weather vane (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, Tab. III (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 6d. Weather vane of Marinoni’s Observatory (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, Tab. III (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

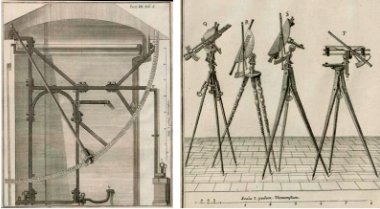

The telescope for transit observations of fixed stars is notable for its extraordinarily stable and meticulous design, which gives Marinoni good marks as an engineer. Marinoni also constructed entirely new quadrants for the southern and northern meridian. In addition to the built-in instruments, Marinoni also had portable devices for astronomical purposes, and geodetic instruments.

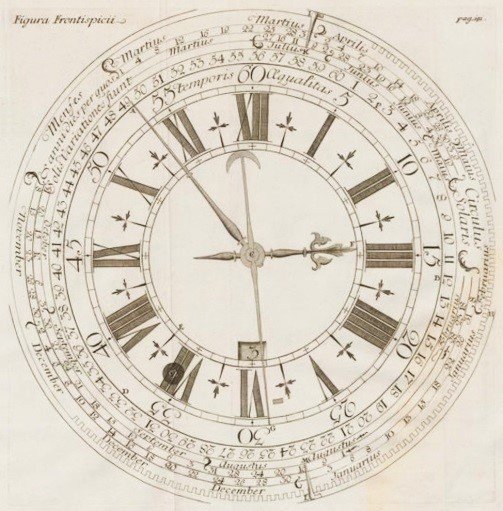

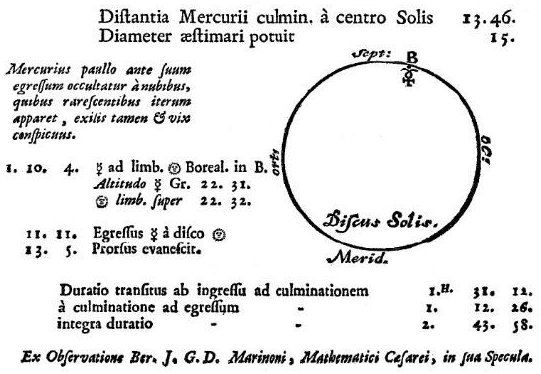

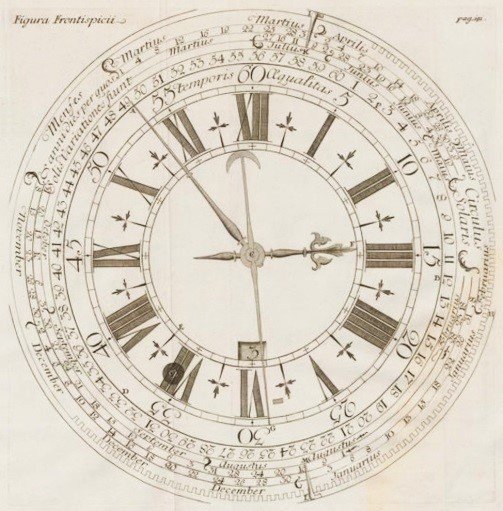

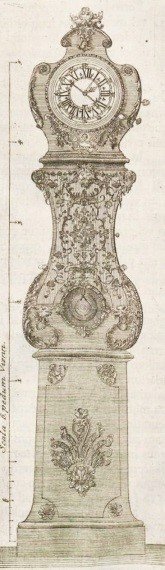

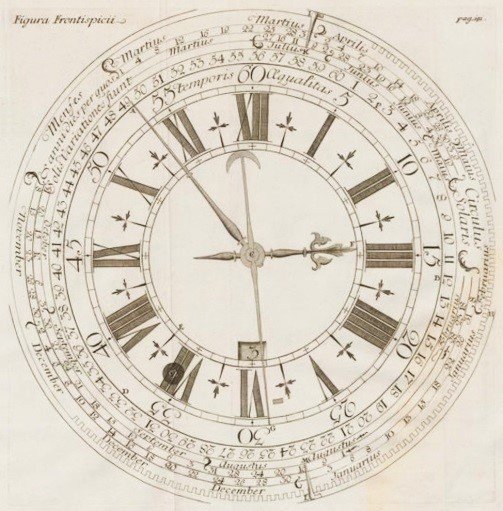

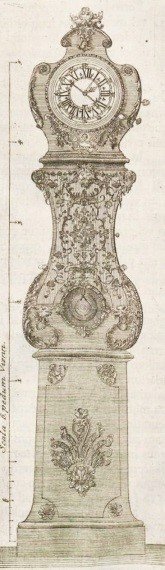

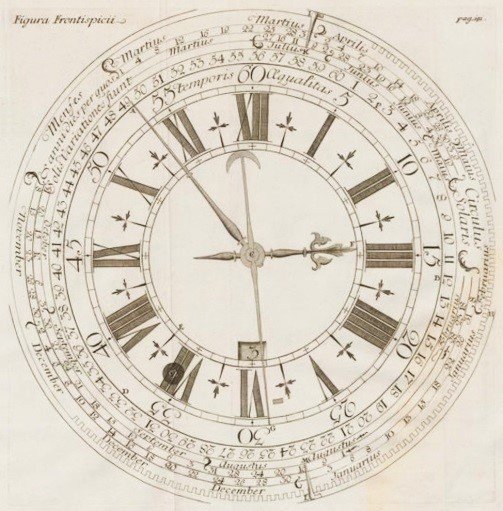

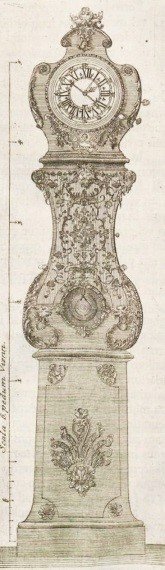

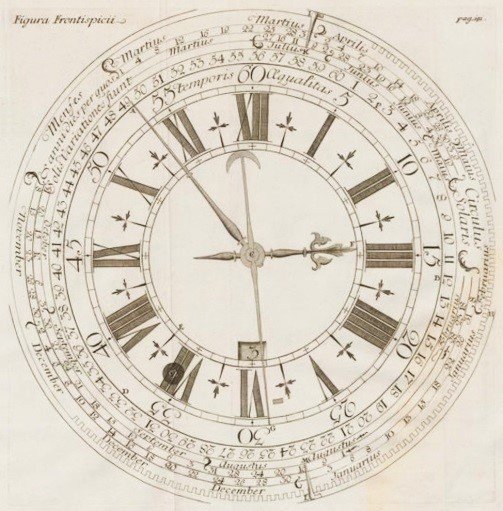

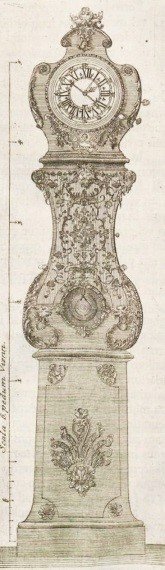

The exact clocks made in London, Paris and Vienna were also of great importance. In particular, the pendulum clock from Paris was a special "equatorial clock" which, in addition to the mean solar time, also displayed the true solar time by means of a own scale. This scale was controlled by a cam disk, which took into account the difference between mean and true solar time of up to approx. ±16 minutes (Equation of Time).

Altogether Marinoni describes 19 instruments: 2 heavy, iron meridian mural quadrants, 1 transit instrument, 3 pendulum clocks, 5 larger transportable quadrants, 4 smaller transportable goniometers, 6 telescopes, 1 celestial globe with a diameter of 24-inch = 63.2cm, made by Joan Blaeu (1596--1673).

The instruments were equipped with the best screw or thread micrometers. The richness and quality of the furnishings can be explained by the fact that the emperor paid quite a bit for the training of his engineers, officers and master builders.

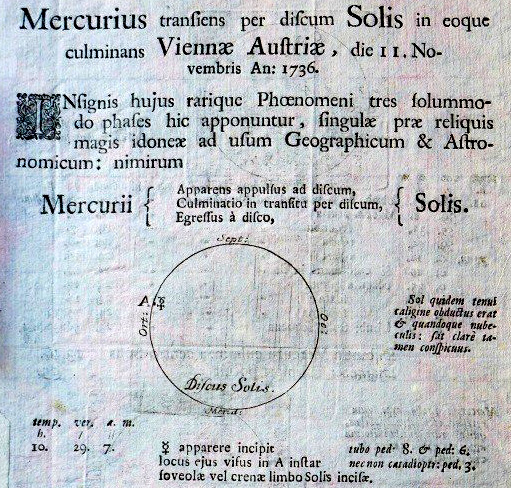

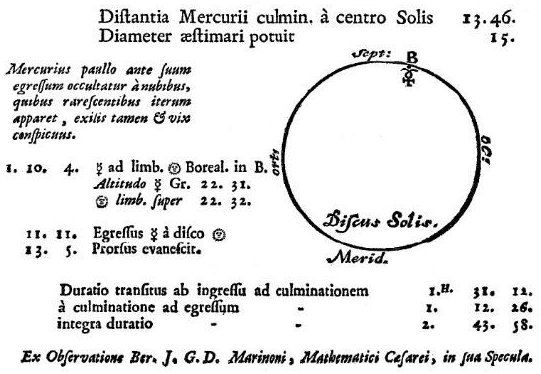

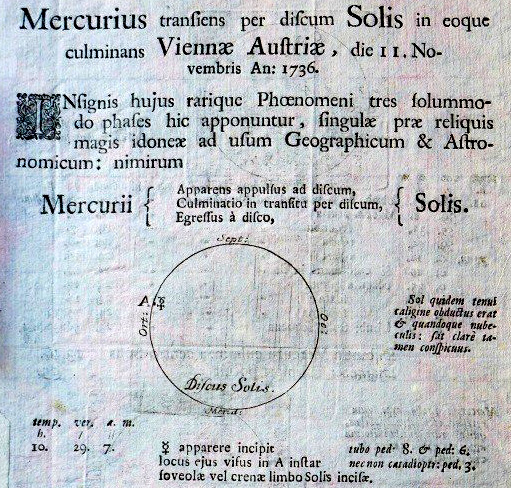

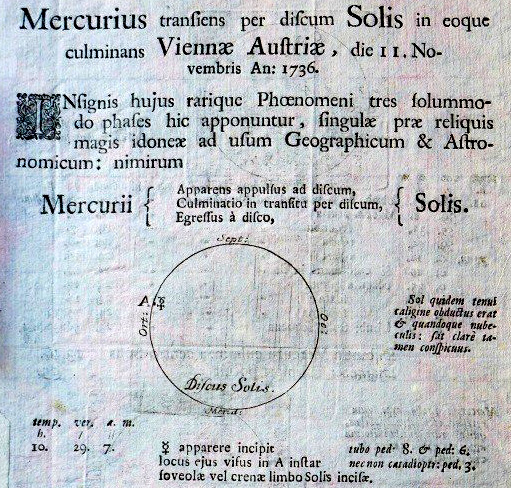

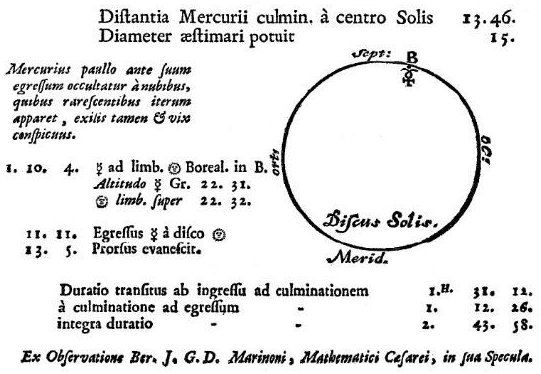

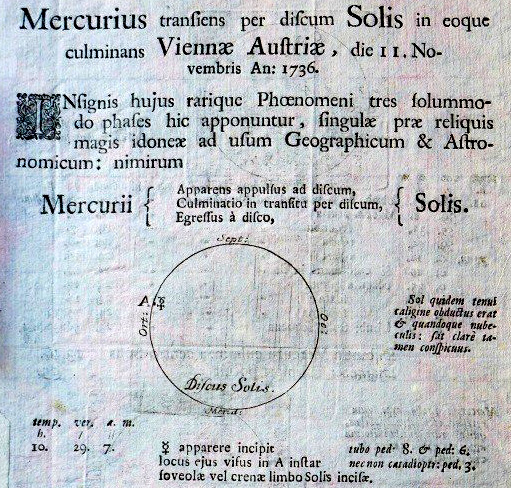

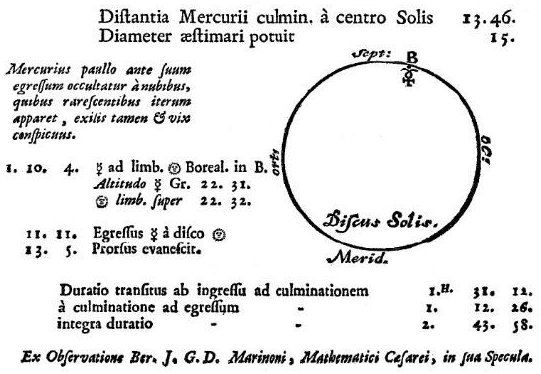

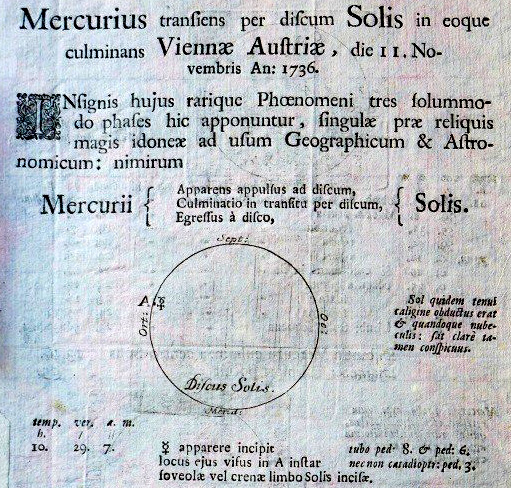

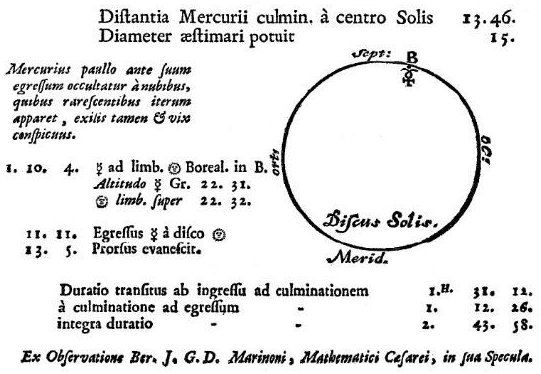

Fig. 7a. "Mercurius transiens per discum Solis in eoque culminans Viennae Austriae, the 11 novembris Anno: 1736" (Biblioteca comunale Udine, Sign. Misc. 36 32, 1/5472)

Fig. 7b. "Report about the Mercury transit in Vienna (1736) from «Mémoires pour l’histoire des sciences et des beaux-arts» (1738), p. 99 f (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k30670d/f98.item.zoom)

The description of his observatory made Marinoni famous throughout Europe and he corresponded with all the luminaries of his time. Marinoni observed the Mercury transit in Vienna on November 11, 1736. His observation report "Mercurius transiens per discum Solis" was published in 1738 in the monthly journal Mémoires pour l’histoire des sciences et des beaux-arts.

Marinoni’s passion for astronomy and new technology makes his observatory and library a magnet for scholars visiting Vienna and mentions that e.g. Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis, Giuseppe Bini, Apostolo Zeno, Maffei, Florio and Rolandi visited the private observatory. Leonhard Euler asked Marinoni to transmit further moon observations.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 7

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-31 17:05:05

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

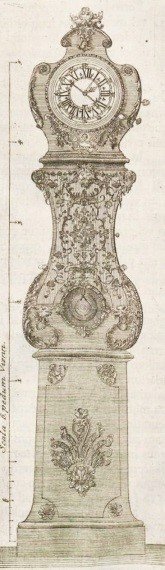

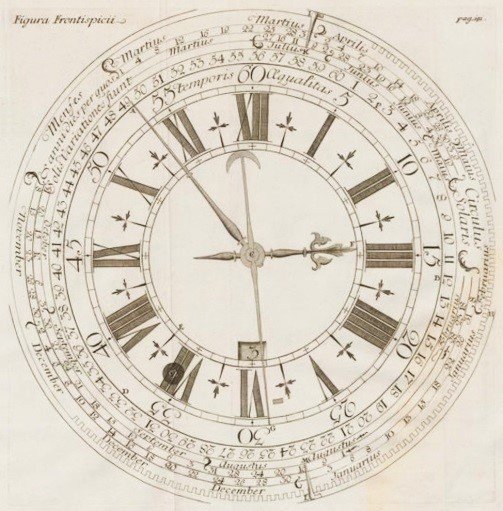

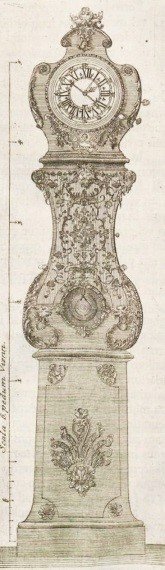

Fig. 8a. Parisian equatorial clock by Alexandre Le Faucheur, in which the position of an additional scale was controlled by a cam disc in order to also display true solar time ("mechanical sundial"); on the dial above XII is inscribed: "Temporis Aequalitas"; Time displayed (mean solar time): 2h53m29s (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber II, p. 186 (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 8b. Parisian equatorial clock by Alexandre Le Faucheur, artistically designed (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber II, p. 191 (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Instruments

- Southern and Northern heavy iron meridian mural quadrants

- Transit instrument

- 3 pendulum clocks, made in London, Paris and Vienna

- 5 larger transportable quadrants

- 4 smaller transportable goniometers

- 6 telescopes

- Celestial globe with a diameter of 24-inch = 63.2cm, made by Joan Blaeu (1596--1673).

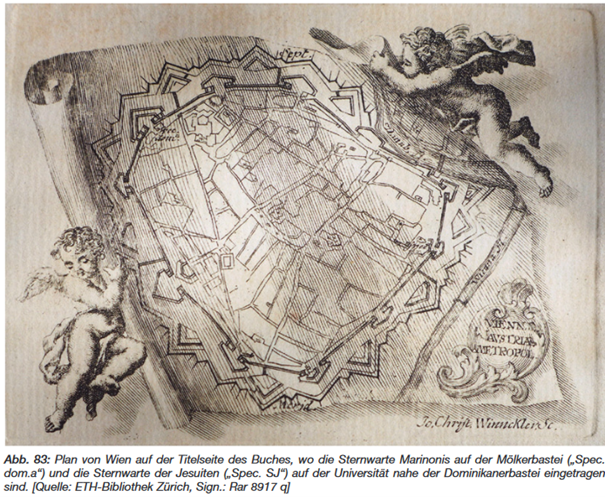

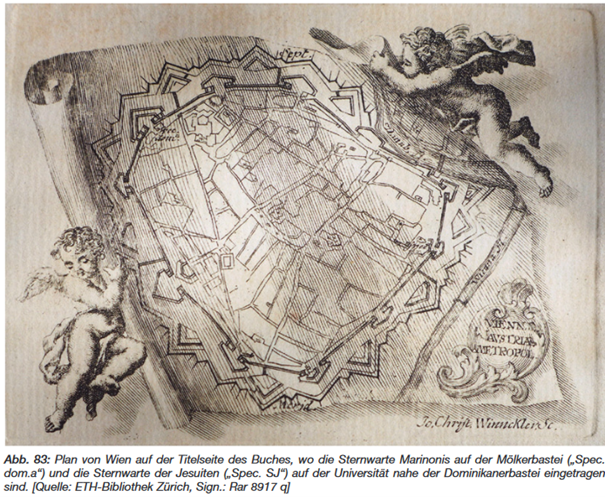

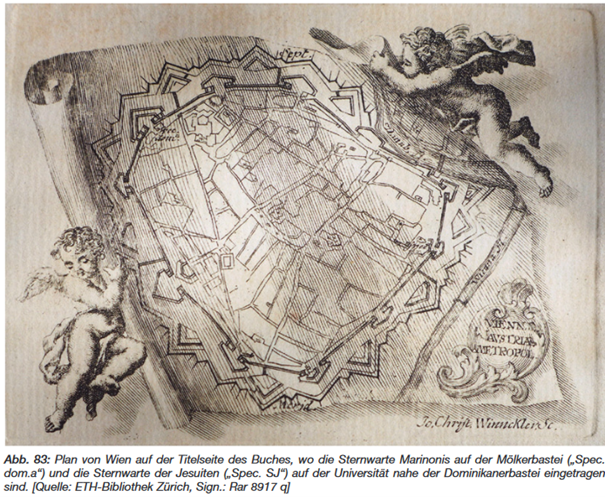

Fig. 9a. Map of Vienna, where the Marinonis observatory on the Mölkerbastei (Spec. dom. a) and the observatory of the Jesuit College (Spec. SJ) near the Dominican bastion are marked (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 9b. Southern mural quadrant and geodetic instruments (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber II, Tab. I after p. 78 and Tab. IX after p. 114 (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Marinoni’s Scientific Achievements

Giovanni Giacomo Marinoni’s merits are: He was appointed as court mathematician (1703), director of the Mathematical and Engineering Academy (1717), one of the first Polytechnical Schools in Europe, in addition, he was cartographer of Vienna (Anguissola-Marinoni map of Vienna, 1704) and of Milan (cadastral land register, 1719--1729), and published surveying books: "De re ichnographica" (Vienna 1751) and "De re ichnometrica" (Vienna 1775).

As astronomer, Marinoni published De astronomica specula domestica (1745) with a detailed description of his private observatory on Mölkerbastei, sponsered by the Imperial court, and of his collection of astronomical and geodetical instruments. He was active in positional and transit astronomy, observations of the Jupiter satellites, and the Transit of Mercury (1736), published as "Mercurius transiens per discum Solis" (1738).Marinoni had good contacts to famous astronomers all over Europe (Hiermanseder & König, 2020) and corresponded with e.g. Leonhard Euler (1707--1783), Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz (1646--1716), Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (1698--1759), Joseph-Nicolas Delisle (1688--1768), Christfried Kirch (1694--1740) oder Sámuel Mikovíny (1686/98--1750). Marinoni was external member of the Royal Prussian Society of Sciences (1746), and honorary member of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg (1746).

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-31 16:16:12

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

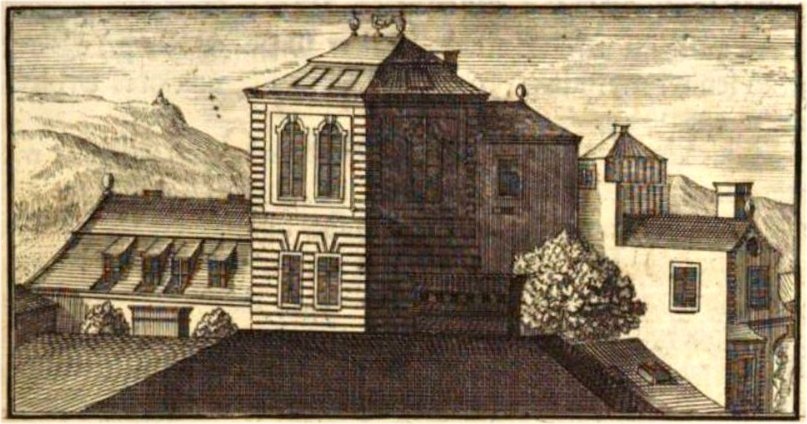

Fig. 10. Pasqualati house (1797), built on the ramp of the former town fortifications (Mölker bastion), view from Universitätsring around 1904-1905 (Photograph by August Stauda, Wien Museum, Inv.-Nr. 29468; CC0 licence)

The Marinoni Observatory (Mölkerbastei 8) is no longer existing.

It is replaced by the Pasqualati house (1797), built on the ramp of the former town fortifications (Mölker bastion). The architect was Peter Mollner (1732--1801), who erected the Pasqualati house for Empress Maria Theresa’s personal physician, Joseph Benedikt, Baron Pasqualati von Osterberg (1733--1799); it was a residence of Ludwig van Beethoven between 1804 and 1814.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 19:40:50

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Marinoni Observatory (Mölkerbastei 8) is built on the former town fortifications; other examples of observatories on fortifications: Nuremberg Castle Eimmart’s Observatory (1678--1757), Oude Sterrewacht Leiden (1633--1860) and Sonnenborgh Observatory Utrecht (1853, now museum) observatories.

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 19:28:16

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Marinoni Observatory is no longer existing.

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 18:32:57

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no information available

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-31 16:17:35

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

No astronomical relevance today, but Marinoni’s publications show his merits in astronomy and cartography.

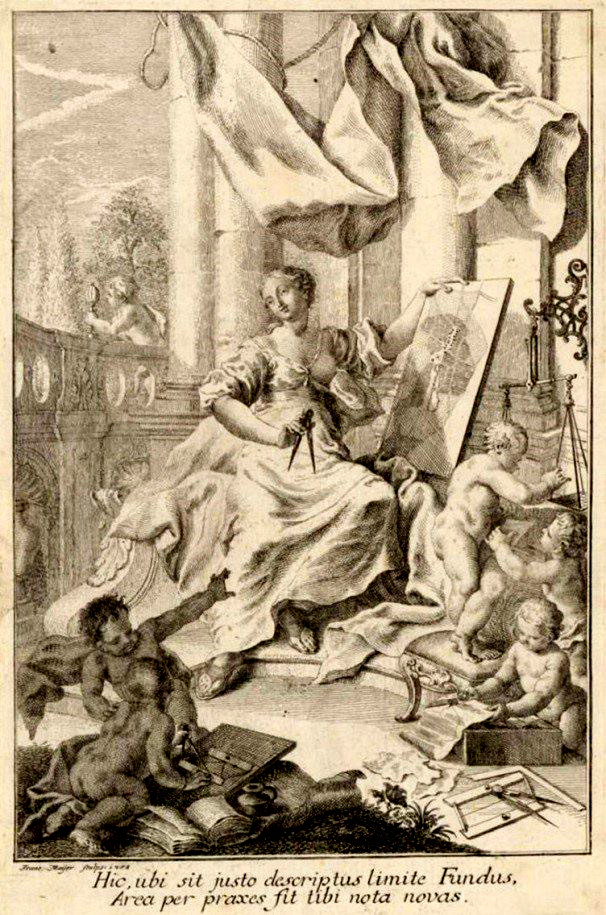

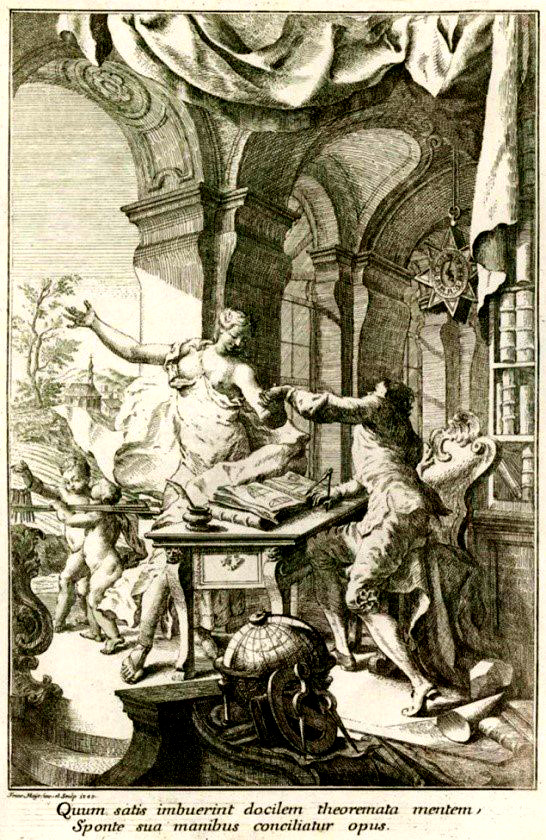

Fig. 11a. Frontispiece of Marinoni’s book "De re ichnographica" (1751), Marinoni, inspired by "Mathematica", led out into the landscape in order to take measurements (Quelle: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 771 q)

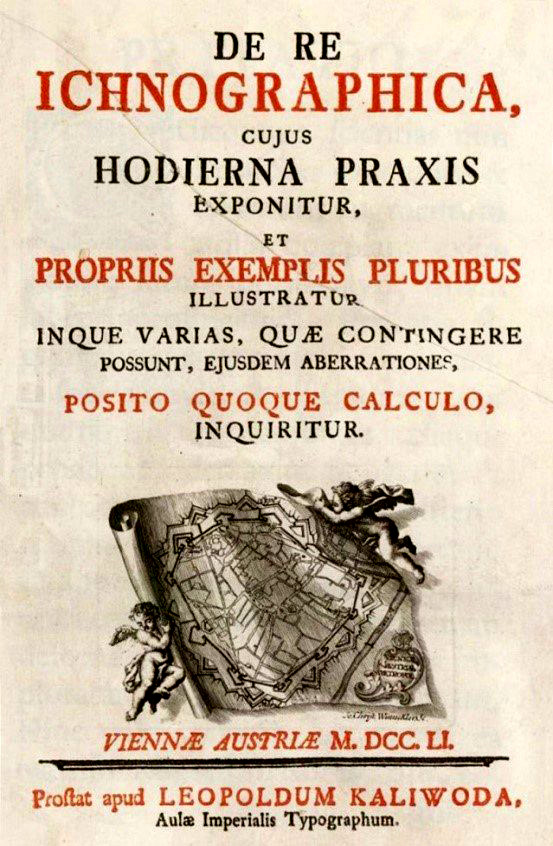

Fig. 11b. Marinoni’s book "De re ichnographica" (1751), like in the book from 1745, the map of Vienna is shown on the title page (Quelle: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 771 q)

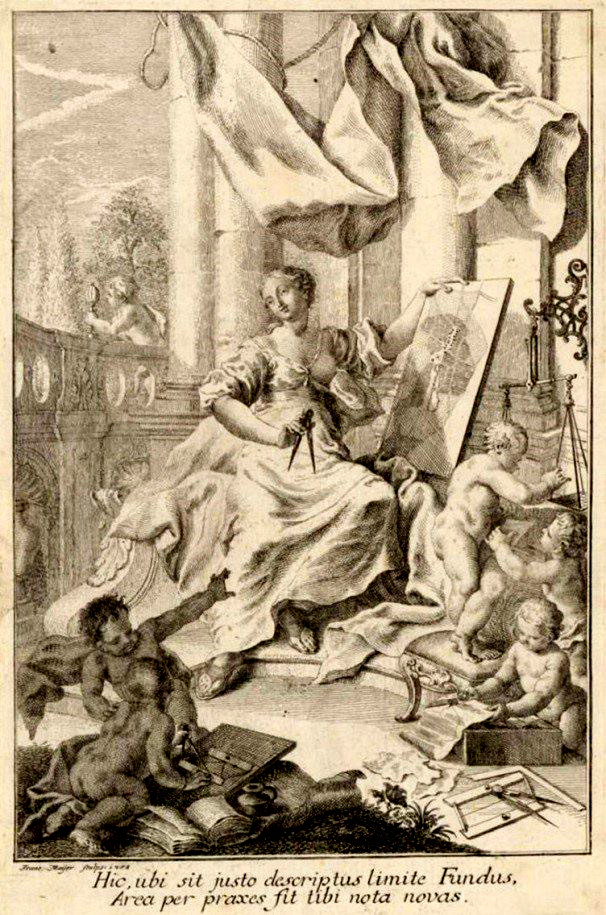

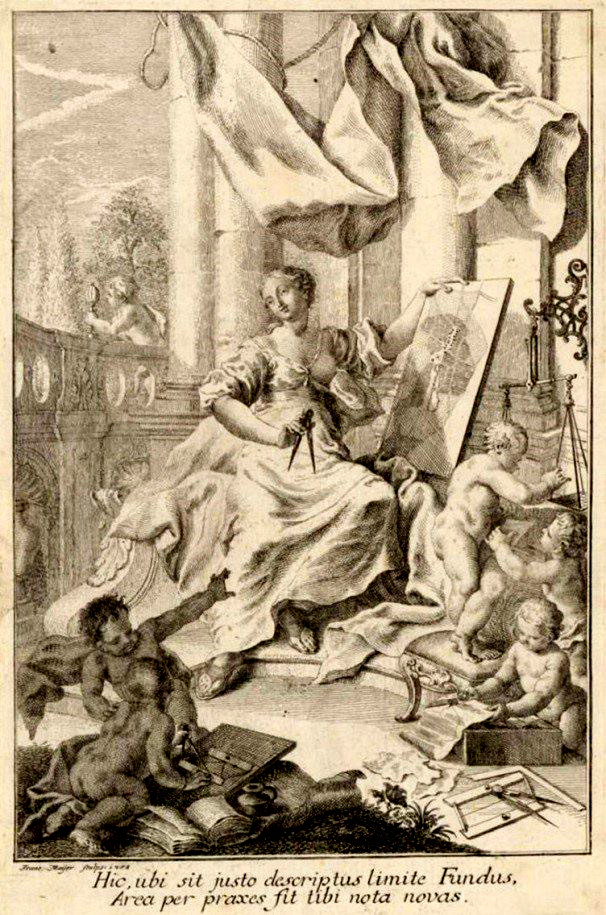

Fig. 11c. Frontispiece of Marinoni’s book "De re ichnographica" (Wien 1775) (Quelle: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 1072 q)

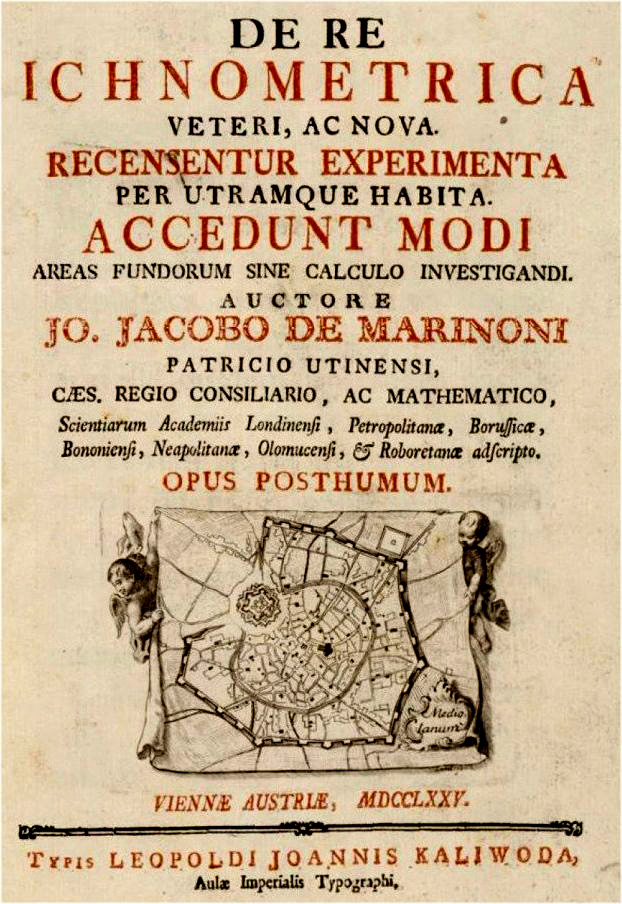

Fig. 11d. Title page with city map of Milan (Mediolanum) of Marinoni’s book "De re ichnographica" (Wien 1775) (Quelle: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 1072 q)

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-04-10 16:26:48

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Anguissola, Leandro & Giovanni Giacomo Marinoni: Accuratissima Viennae Austriae ichnographica delineatio. Vienna: inc. J.A. Pfeiffel & C. Englebrecht 1706.

- Bortolan, Pirona Eugenio: Vita e opere di Gian Giacomo Marinoni. In: Marinoni Istituto Tecnico Statale per Geometri 1961--2011. 50 anni dalla Fondazione. Udine 2012.

- Bredekamp, Horst & Wladimir Velminski (Hg.): Mathesis & Graphé: Leonhard Euler und die Entfaltung der Wissenssysteme. Berlin: Akademie 2010.

- Candiloro Ignazio: Giovanni Giacomo Marinoni matematico, topografo e astronomo udinese. In: L’Universo 52 (1972), 2, p. 428-438.

- Cargnelutti, Liliana: Marinoni. sine anno, cf. http://www.dizionariobiograficodeifriulani.it/marinoni-giovanni-giacomo/.

- Cavagna, Anna Giulia: I libri di Giovanni Giacomo Marinoni. In: Gli spazi del libro nell’Europa del XVIII secolo, a cura di Maria Gioia Tavoni e Françoise Waquet. Bologna: Pàtron 1997, p. 129-152.

- Cavagna, Anna Giulia: Opere e libri di un astronomo cartografo del XVIII secolo: tra erudizione e Stato. In: Nuncius - Annali di storia della scienza XIII (1998), fasc. 2, p. 461-491.

http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/182539198x00509. - Cavagna, Anna Giulia: A Free Transmission of Knowledge: The Literary Gifts and Reception of an Eighteenth-Century Scholar. In: Printing for Free: Non Commercial Publishing in Commercial Societies. Edited by James Raven. Burlington, USA: Ashgate 2000, p. 29-47.

- Cavagna, Anna Giulia: Marinoni, Giovanni Giacomo. In: Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 70. Rom 2008, p. 425-445.

- Gatti, Bertram: Prinz Eugen und die Ingenieur-Akademie. In: Oesterreichische militärische Zeitschrift (1866), Bd. I.

- Gatti, Friedrich: Geschichte der K.K. Ingenieur- und K.K. Genie-Akademie, 1717--1869. Wien 1901.

- Fox, Dirk & Thomas Püttmann: Technikgeschichte mit fischertechnik. Heidelberg 2015.

- Hanne, Egghardt: Prinz Eugen, der Philosoph in Kriegsrüstung. Facetten einer außergewöhnlichen Persönlichkeit. Wien: Kremayr & Scheriau 2013.

- Hiermanseder Michael: Wie sich die Bilder gleichen! Der Mailänder Kataster von 1718 als Vorbild für die preußische Katastervermessung im Herzogtum Magdeburg 1720. In: Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) 4 (2017), p. 235 ff.

- Hiermanseder Michael: Aus der Korrespondenz von Johann Jakob von Marinoni mit Leonhard Euler 1736--1751 "... quasdam meditationes Tecumque communicare, quas ut benevole accipias, Tuumque de iis judicium perscribas, etiam atque etiam rogo." From the correspondence of Jacopo de Marinoni with Leonhard Euler 1736--1751 "... and to share some considerations with you, so that you receive them benevolently, and write down your judgement about them, I ask you again." In: Vermessung & Geoinformation 2 (2018) and 4 (2018), p. 264--305.

- Hiermanseder, Michael & Heinz König: Johann Jakob von Marinoni -- geadelt und getadelt. Schöpfer des Mailänder Katasters, Kartograph, Wissenschaftler. In: Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) 2 (2017), p. 60 ff.

- Hiermanseder, Michael & Heinz König: Johann Jakob von Marinoni und der Mailänder Kataster von 1718. In: DVW-Bayern 2 (2018), p. 145--167.

- Hiermanseder, Michael & Heinz König: Johann Jakob von Marinoni -- Mathematiker, Astronom, Geodät -- Internationale Kontakte eines Wissenschaftlers im Wien des 18. Jahrhunderts. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Internationalität in der astronomischen Forschung (18. bis 21. Jahrhundert). Internationality in the Astronomical Research (18th to 21st Century). Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Wien 2018. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis; Vol. 49) 2020, p. 150--195.

- Hiermanseder, Michael, private communication (2022).

- König, Heinz: Der Vermesser, Mathematiker und Astronom Johann Jakob Marinoni und die Josefstadt. In: Aus der Josefstadt in die Welt. Landkarten aus dem 8ten. Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung im Bezirksmuseum Josefstadt, 9. März 2017 bis 20. Dezember 2017. Wien 2017, p. 92-122.

- Kremer, Aloys Sylvester: Darstellung des Steuerwesens, II. Theil. Wien 1821.

- Lego, Karl: Geschichte des Österreichischen Grundkatasters. Wien: BEV 1968.

- Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm: Sämtliche Schriften und Briefe. Hannover 2016. https://leibnizedition.de/.

- Lühning, Felix: "Wo aber bleiben wir Teutschen?" Johann Jakob Marinoni (Wien) und die Instrumentierung einer Sternwarte um 1720. In: Hamel, Jürgen (Hg.): Beiträge des Kolloquiums "Gottfried Kirch und die Berliner Astronomie im 18. Jahrhundert" in Berlin-Trepow am 6.3.2010. Frankfurt am Main: Harri Deutsch (Acta Historica Astronomiae, Vol. 41) 2010, p. 154-168.

- Marinoni, Giovanni Giacomo: De astronomia specula domestica et organico apparatu astronomico. Libri duo Reginæ Dicati a Joanne Jacobo Marinonio. Vienna: L.J. Kaliwoda 1745.

- Marinoni, Joannes Jacobus: De re ichnographica, cuius hodierna praxis exponitur et propriis exemplis pluribus illustratur in qua varias, quae contigere possunt, eiusdem aberrationes, posito quoque calculo, inquiritur. Vienna: Kaliwoda 1751.

- Marinoni, Joannes Jacobus: De re ichnometrica veteri et nova: recensentur experimenta per utramque habita, accedunt modi areas fundorum sine calculo investigandi. Vienna: Kaliwoda 1775.

- Marcello, Verga: Il "sogno spagnolo" di Carlo VI. Alcune considerazioni sulla monarchia asburgica e i domini italiani nella prima metà del Settecento. Bologna 1985.

- Oberhummer Eugen: Ein Jagdatlas Kaiser Karl VI. In: Unsere Heimat VI (1933), p. 152-159.

- Pärr, Nora: Wiener Astronomen -- ihre Tätigkeit an Privatobservatorien und Universitätssternwarten. Diplomarbeit an der Geisteswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Wien, 2001.

- Poggendorff, Johann Christian: Biographisch-literarisches Handwörterbuch zur Geschichte der exacten Wissenschaften, Band II. Leipzig: Johann Amrosius Barth 1863.

- Redlich, Oswald: "Weltmacht des Barock." Österreich in der Zeit Kaiser Leopolds I. Wien (4. Auflage) 1961.

- Schmeidler, Felix: Marinoni, Johann Jakob. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB), Band 16. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 1990.

- Seitschek, Stefan; Hutterer, Herbert & Gerald Theimer: 300 Jahre Karl VI. (1711--1740) -- Spuren der Herrschaft des "letzten" Habsburgers. Wien: Österreichisches Staatsarchiv 2011.

- Slezak, Friedrich: Johann Jakob Marinoni (1676-1755). In: Der Donauraum -- Zeitschrift für Donauforschung (1976), Nr. 21, p. 195-207.

- Sofonea, Traian: Johann Jakob von Marinoni (1676--1755) -- Sein Leben und Schaffen -- 300 Jahre nach seiner Geburt. In: ÖZ (1976), p. 97 ff.

- Steinmayr, Johann: Die alte Wiener Universitätssternwarte unter der Leitung von Jesuiten und Exjesuiten (1755--1816). In: Die Geschichte der Universitäts-Sternwarte Wien -- Vorträge von P.J. Steinmayer S.J. (1932). Siehe: Die Geschichte der Universitätssternwarte Wien: Dargestellt anhand ihrer historischen Instrumente und eines Typoskripts von Johann Steinmayr. Hg. von Hamel, Jürgen; Müller, Isolde & Thomas Posch. Frankfurt am Main (Acta Historica Astronomiae; 38) 2010.

- Virgin, Rosella: Giovanni Giacomo Marinoni (1676-1755). La nascita della cartografia moderna. Venedig: Tesi di Laurea, Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia 1998.

- Zinner, Ernst: Deutsche und niederländische astronomische Instrumente des 11.--18. Jahrhunderts. München: C.H. Beck 1956 (2. Auflage) 1967.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-31 17:02:28

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Anna Giulia Cavagna: MARINONI, Giovanni Giacomo, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 70 (2008).

- Liliana Cargnelutti: MARINONI GIOVANNI GIACOMO (1676--1755), matematico, cartografo

- Gian Giacomo Marinoni (Wikipedia, Furlan)

- Johann Jakob Marinoni (Wikipedia, German)

- Leander Anguissola, Johann Jacob Marinoni: Wien, 1704

- Correspondence of Matinoni (e manuscripta)

Links to external on-line pictures - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 18:32:58

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no information available

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-05-28 03:02:45

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Marinoni Observatory, Mölkerbastei 8, Schreyvogelgasse 16, 1010 Vienna, Austria

(today Pasqualati building)

See also: Observatories in Vienna in the 18th and 19th Century:

- Vienna Jesuit Observatory (1733)

- Old Vienna University Observatory (1754--1879), today Austrian Academy of Sciences

- Kuffner Observatory, Vienna-Ottakring (1886)

- Vienna University Observatory, Wien-Währing (1879)

Location - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 19:43:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude +48°12.7’ N, Longitude 16°21.7’ E, Elevation 180m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 18:32:57

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

-

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-31 16:12:15

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 1a. Marinoni’s private observatory ("De astronomica specula domestica et organico apparatu astronomico" (Wien: Kaliwoda 1745)

Giovanni Jacopo de Marinoni (1676--1755) and his Observatory

![Johann Jakob von [Giovanni Jacopo de] Marinoni (16](/images/astronomicalheritage.net/gallery/ahp_entities/entity000220/H+K_01.jpg)

Fig. 1b. Johann Jakob von [Giovanni Jacopo de] Marinoni (1676--1755), engraving by Ferdinand Landerer, undated (Bildarchiv der ÖNB, © ÖNB Wien, PORT_001211305_01AZ:27249/3/2017)

Fig. 1c. Coat of arms of Giovanni Jacopo de Marinoni (1676--1755) (Nobility Patent of Marinoni)

Giovanni Jacopo de [Johann Jakob] Marinoni (1676--1755) was born in Udine. In 1703, Emperor Leopold I gave him the title of court mathematician, which was confirmed by the following rulers Joseph I, Charles VI, and Maria Theresa until the end of his life.

The Imperial court mathematician erected in the 1720s in Vienna with Imperial support on the roof of his house on the Mölkerbastei (medieval bastion) a two-story tower, which he expanded to an observatory. This private observatory, which he describes in detail in his book, was actually the first observatory in Vienna.

Marinoni was knighted on April 9, 1733. Then, on April 22, 1733, Marinoni was appointed head of the Mathematical and Engineering Academy.

Founding of the first Polytechnical School in Central Europe

Fig. 2a. Patent of December 24, 1717 for the establishment of an engineering academy in Vienna under the direction of Anguissolas and the deputy director Marinoni (OeStA/KA ZSt HKR SR KzlA IV, 9. [© GZ: ÖSTA-2028656/0012-KA/2017])

Fig. 2b. Emperor Charles VI (1685--1740), painting by Johann Gottfried Auerbach (Museum of Military History, Vienna) (Wikipedia)

With an Imperial patent, dated December 24, 1717, Charles VI -- on recommendation Leander [Leandro] Anguissola (1653--1720) and Marinoni -- set up the first academy for military and civil engineers in the hereditary lands, later also known as the Mathematical and Engineering Academy, and appointed the proponents to be its directors (König 2017, p. 99 f).

Prince Eugene reports to Emperor Charles VI on May 17, 1718 that 45 students, including noble persons, philosophers and artists, were admitted and what progress they had made. Tuition was free, material expenses were low, but the salaries of the directors for part-time work were quite generous.

Marinoni as Cartographer and Court Mathematician

Fig. 3. The map of Vienna (1706) by Anguissola-Marinoni-Hildebrandt-Steinhausen (reprinted 1987) (https://1030wien.at/geschichte/historische-landkarten)

In 1704, Emperor Leopold I commissioned Anguissola and Marinoni to plan the line wall on the outer border of Vienna. In the same year, the famous Anguissola-Marinoni map of Vienna was created with the involvement of the court architect Lukas von Hildebrandt and the city engineer Arnold von Steinhausen (copper engraving 1706, reprint 1710), on which the fortifications are drawn. The inclusion of the suburbs in the truce and jurisdiction of the Imperial Capital and Residence City of Vienna by decree of July 15, 1689 resulted in the need for a city plan of the new, larger Vienna.

Marinoni is justifiably proud of the quality of its map renderings. The 300-year-old Milan cadastre (1719--1729, 16 large map sheets at a scale of 1:72,000) is the first cadastre to be drawn up based on the survey of an entire, contiguous country. In 1777, a copper-engraved map consisting of 9 sheets, reduced to a scale of 1:90,000, was created in Milan ("Carta Topografica dello Stato di Milano seconda la Misura Censuaria"). Marinoni is regarded as a model for the cadastral surveys of the 19th century.

Many of the maps and plans, which Marinoni created under the auspices of the Austrian Imperial family, have survived, and they not only represent a technical masterpiece, but are also priceless cultural assets of unsurpassed beauty. His two masterworks, describing his surveying activites, are "De re ichnographica" (Vienna 1751, Making maps and plans) and "De re ichnometrica" (Vienna 1775, The Surveying Technology).

Fig. 4a. Measuring table, invented by Johannes Prätorius [Johann Richter] (1537--1616), improved by Marinoni ("De re ichnographica" (1751), Graphic 24, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 771 q)

Fig. 4b. Measuring table, invented by Johannes Prätorius [Johann Richter] (1537--1616), improved by Marinoni ("De re ichnographica" (1751), Graphic 11, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 771 q)

When surveying Vienna, Marinoni used the measuring table, invented by Johannes Prätorius [Johann Richter] (1537--1616), professor of the Nuremberg University in Altdorf. But Marinoni had improved it by fitting a larger table on the top and he used a more stable tripod. Since then, he has used this new measuring table regularly and made constant efforts to perfect it. Finally, in 1714, he constructed the final version with which he carried out the cadastral survey of Milan. His improvements to the measuring table, consisted in enlarging the diopter ruler and also attaching a mountain diopter to it for strongly inclined sights, and he also designed a circular and a linear displacement option for the table top in two mutually perpendicular directions in order to be able to precisely adjust the measuring table over the position.

Fig. 4c. Application of the Planimetric Balance for area determination and production of standardized foils (Marinoni: "De re ichnometrica" (1775), frontispice, Tab. I, p. 231, Tab. IV, p. 239, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 1072 q)

Marinoni as Astronomer

Fig. 5a. The house of the court mathematician Marinoni on the Mölkerbastei with the astronomical observation tower (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, p. 1, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 5b. Some of Marinoni’s astronomical instruments (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 5c. Frontispice of Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745 (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Marinoni had the first observatory in Vienna set up in his private home on the Mölkerbastei in the 1720s, for which he had the most modern observation instruments, purchased at the Emperor’s expense, as he wrote in 1745 in his book De astronomica specula domestica et organico apparatu astronomico libri duo Reginae dicati a Joanne Jacobo Marinonio patricio utinensi, etc. described. In the dedication of De astronomica specula to Maria Theresa, Marinoni first praises the generous support of her late father Charles VI. for its observatory.

Due to the heights of the Vienna Woods (Wiener Wald), the Marinonis Observatory only had lack of horizon view, with the result that rising and setting points of the celestial bodies were often not precisely ascertainable, and there was also fog from the Danube lowlands.

The house is also rotated 45° from the meridian. Marinoni therefore concentrated on positional and transit astronomy, observations of the corresponding altitudes in order to precisely determine the meridian, culmination observations and tracking the Jupiter satellites.

In the description of his observatory in "De astronomica specula domestica", sections of the building illustrate the high windows, the wooden roof beams, the narrow gallery with the iron handrail and the observation pendulum clock.

On the roof of the astronomical tower, there was a weather vane in the form of a rooster, which was also Marinoni’s heraldic animal, connected by a vertical shaft to a pointer that showed the wind direction on a compass rose on the ceiling of the main room of the observatory, which could be read without having to go outside.

Fig. 6a. Astronomical observation tower on Marinoni’s house on the Mölkerbastei, with astronomical instruments (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, Tab. II (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 6b. Astronomical observation tower on Marinoni’s house on the Mölkerbastei, with astronomical instruments, with a weather vane (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, Tab. IV (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 6c. Marinoni’s Observatory on the Mölkerbastei with a weather vane (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, Tab. III (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 6d. Weather vane of Marinoni’s Observatory (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, Tab. III (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

The telescope for transit observations of fixed stars is notable for its extraordinarily stable and meticulous design, which gives Marinoni good marks as an engineer. Marinoni also constructed entirely new quadrants for the southern and northern meridian. In addition to the built-in instruments, Marinoni also had portable devices for astronomical purposes, and geodetic instruments.

The exact clocks made in London, Paris and Vienna were also of great importance. In particular, the pendulum clock from Paris was a special "equatorial clock" which, in addition to the mean solar time, also displayed the true solar time by means of a own scale. This scale was controlled by a cam disk, which took into account the difference between mean and true solar time of up to approx. ±16 minutes (Equation of Time).

Altogether Marinoni describes 19 instruments: 2 heavy, iron meridian mural quadrants, 1 transit instrument, 3 pendulum clocks, 5 larger transportable quadrants, 4 smaller transportable goniometers, 6 telescopes, 1 celestial globe with a diameter of 24-inch = 63.2cm, made by Joan Blaeu (1596--1673).

The instruments were equipped with the best screw or thread micrometers. The richness and quality of the furnishings can be explained by the fact that the emperor paid quite a bit for the training of his engineers, officers and master builders.

Fig. 7a. "Mercurius transiens per discum Solis in eoque culminans Viennae Austriae, the 11 novembris Anno: 1736" (Biblioteca comunale Udine, Sign. Misc. 36 32, 1/5472)

Fig. 7b. "Report about the Mercury transit in Vienna (1736) from «Mémoires pour l’histoire des sciences et des beaux-arts» (1738), p. 99 f (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k30670d/f98.item.zoom)

The description of his observatory made Marinoni famous throughout Europe and he corresponded with all the luminaries of his time. Marinoni observed the Mercury transit in Vienna on November 11, 1736. His observation report "Mercurius transiens per discum Solis" was published in 1738 in the monthly journal Mémoires pour l’histoire des sciences et des beaux-arts.

Marinoni’s passion for astronomy and new technology makes his observatory and library a magnet for scholars visiting Vienna and mentions that e.g. Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis, Giuseppe Bini, Apostolo Zeno, Maffei, Florio and Rolandi visited the private observatory. Leonhard Euler asked Marinoni to transmit further moon observations.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 7

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-31 17:05:05

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 8a. Parisian equatorial clock by Alexandre Le Faucheur, in which the position of an additional scale was controlled by a cam disc in order to also display true solar time ("mechanical sundial"); on the dial above XII is inscribed: "Temporis Aequalitas"; Time displayed (mean solar time): 2h53m29s (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber II, p. 186 (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 8b. Parisian equatorial clock by Alexandre Le Faucheur, artistically designed (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber II, p. 191 (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Instruments

- Southern and Northern heavy iron meridian mural quadrants

- Transit instrument

- 3 pendulum clocks, made in London, Paris and Vienna

- 5 larger transportable quadrants

- 4 smaller transportable goniometers

- 6 telescopes

- Celestial globe with a diameter of 24-inch = 63.2cm, made by Joan Blaeu (1596--1673).

Fig. 9a. Map of Vienna, where the Marinonis observatory on the Mölkerbastei (Spec. dom. a) and the observatory of the Jesuit College (Spec. SJ) near the Dominican bastion are marked (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 9b. Southern mural quadrant and geodetic instruments (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber II, Tab. I after p. 78 and Tab. IX after p. 114 (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Marinoni’s Scientific Achievements

Giovanni Giacomo Marinoni’s merits are: He was appointed as court mathematician (1703), director of the Mathematical and Engineering Academy (1717), one of the first Polytechnical Schools in Europe, in addition, he was cartographer of Vienna (Anguissola-Marinoni map of Vienna, 1704) and of Milan (cadastral land register, 1719--1729), and published surveying books: "De re ichnographica" (Vienna 1751) and "De re ichnometrica" (Vienna 1775).

As astronomer, Marinoni published De astronomica specula domestica (1745) with a detailed description of his private observatory on Mölkerbastei, sponsered by the Imperial court, and of his collection of astronomical and geodetical instruments. He was active in positional and transit astronomy, observations of the Jupiter satellites, and the Transit of Mercury (1736), published as "Mercurius transiens per discum Solis" (1738).Marinoni had good contacts to famous astronomers all over Europe (Hiermanseder & König, 2020) and corresponded with e.g. Leonhard Euler (1707--1783), Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz (1646--1716), Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (1698--1759), Joseph-Nicolas Delisle (1688--1768), Christfried Kirch (1694--1740) oder Sámuel Mikovíny (1686/98--1750). Marinoni was external member of the Royal Prussian Society of Sciences (1746), and honorary member of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg (1746).

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-31 16:16:12

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 10. Pasqualati house (1797), built on the ramp of the former town fortifications (Mölker bastion), view from Universitätsring around 1904-1905 (Photograph by August Stauda, Wien Museum, Inv.-Nr. 29468; CC0 licence)

The Marinoni Observatory (Mölkerbastei 8) is no longer existing.

It is replaced by the Pasqualati house (1797), built on the ramp of the former town fortifications (Mölker bastion). The architect was Peter Mollner (1732--1801), who erected the Pasqualati house for Empress Maria Theresa’s personal physician, Joseph Benedikt, Baron Pasqualati von Osterberg (1733--1799); it was a residence of Ludwig van Beethoven between 1804 and 1814.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 19:40:50

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Marinoni Observatory (Mölkerbastei 8) is built on the former town fortifications; other examples of observatories on fortifications: Nuremberg Castle Eimmart’s Observatory (1678--1757), Oude Sterrewacht Leiden (1633--1860) and Sonnenborgh Observatory Utrecht (1853, now museum) observatories.

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 19:28:16

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Marinoni Observatory is no longer existing.

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 18:32:57

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no information available

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-31 16:17:35

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

No astronomical relevance today, but Marinoni’s publications show his merits in astronomy and cartography.

Fig. 11a. Frontispiece of Marinoni’s book "De re ichnographica" (1751), Marinoni, inspired by "Mathematica", led out into the landscape in order to take measurements (Quelle: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 771 q)

Fig. 11b. Marinoni’s book "De re ichnographica" (1751), like in the book from 1745, the map of Vienna is shown on the title page (Quelle: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 771 q)

Fig. 11c. Frontispiece of Marinoni’s book "De re ichnographica" (Wien 1775) (Quelle: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 1072 q)

Fig. 11d. Title page with city map of Milan (Mediolanum) of Marinoni’s book "De re ichnographica" (Wien 1775) (Quelle: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 1072 q)

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-04-10 16:26:48

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Anguissola, Leandro & Giovanni Giacomo Marinoni: Accuratissima Viennae Austriae ichnographica delineatio. Vienna: inc. J.A. Pfeiffel & C. Englebrecht 1706.

- Bortolan, Pirona Eugenio: Vita e opere di Gian Giacomo Marinoni. In: Marinoni Istituto Tecnico Statale per Geometri 1961--2011. 50 anni dalla Fondazione. Udine 2012.

- Bredekamp, Horst & Wladimir Velminski (Hg.): Mathesis & Graphé: Leonhard Euler und die Entfaltung der Wissenssysteme. Berlin: Akademie 2010.

- Candiloro Ignazio: Giovanni Giacomo Marinoni matematico, topografo e astronomo udinese. In: L’Universo 52 (1972), 2, p. 428-438.

- Cargnelutti, Liliana: Marinoni. sine anno, cf. http://www.dizionariobiograficodeifriulani.it/marinoni-giovanni-giacomo/.

- Cavagna, Anna Giulia: I libri di Giovanni Giacomo Marinoni. In: Gli spazi del libro nell’Europa del XVIII secolo, a cura di Maria Gioia Tavoni e Françoise Waquet. Bologna: Pàtron 1997, p. 129-152.

- Cavagna, Anna Giulia: Opere e libri di un astronomo cartografo del XVIII secolo: tra erudizione e Stato. In: Nuncius - Annali di storia della scienza XIII (1998), fasc. 2, p. 461-491.

http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/182539198x00509. - Cavagna, Anna Giulia: A Free Transmission of Knowledge: The Literary Gifts and Reception of an Eighteenth-Century Scholar. In: Printing for Free: Non Commercial Publishing in Commercial Societies. Edited by James Raven. Burlington, USA: Ashgate 2000, p. 29-47.

- Cavagna, Anna Giulia: Marinoni, Giovanni Giacomo. In: Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 70. Rom 2008, p. 425-445.

- Gatti, Bertram: Prinz Eugen und die Ingenieur-Akademie. In: Oesterreichische militärische Zeitschrift (1866), Bd. I.

- Gatti, Friedrich: Geschichte der K.K. Ingenieur- und K.K. Genie-Akademie, 1717--1869. Wien 1901.

- Fox, Dirk & Thomas Püttmann: Technikgeschichte mit fischertechnik. Heidelberg 2015.

- Hanne, Egghardt: Prinz Eugen, der Philosoph in Kriegsrüstung. Facetten einer außergewöhnlichen Persönlichkeit. Wien: Kremayr & Scheriau 2013.

- Hiermanseder Michael: Wie sich die Bilder gleichen! Der Mailänder Kataster von 1718 als Vorbild für die preußische Katastervermessung im Herzogtum Magdeburg 1720. In: Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) 4 (2017), p. 235 ff.

- Hiermanseder Michael: Aus der Korrespondenz von Johann Jakob von Marinoni mit Leonhard Euler 1736--1751 "... quasdam meditationes Tecumque communicare, quas ut benevole accipias, Tuumque de iis judicium perscribas, etiam atque etiam rogo." From the correspondence of Jacopo de Marinoni with Leonhard Euler 1736--1751 "... and to share some considerations with you, so that you receive them benevolently, and write down your judgement about them, I ask you again." In: Vermessung & Geoinformation 2 (2018) and 4 (2018), p. 264--305.

- Hiermanseder, Michael & Heinz König: Johann Jakob von Marinoni -- geadelt und getadelt. Schöpfer des Mailänder Katasters, Kartograph, Wissenschaftler. In: Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) 2 (2017), p. 60 ff.

- Hiermanseder, Michael & Heinz König: Johann Jakob von Marinoni und der Mailänder Kataster von 1718. In: DVW-Bayern 2 (2018), p. 145--167.

- Hiermanseder, Michael & Heinz König: Johann Jakob von Marinoni -- Mathematiker, Astronom, Geodät -- Internationale Kontakte eines Wissenschaftlers im Wien des 18. Jahrhunderts. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Internationalität in der astronomischen Forschung (18. bis 21. Jahrhundert). Internationality in the Astronomical Research (18th to 21st Century). Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Wien 2018. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis; Vol. 49) 2020, p. 150--195.

- Hiermanseder, Michael, private communication (2022).

- König, Heinz: Der Vermesser, Mathematiker und Astronom Johann Jakob Marinoni und die Josefstadt. In: Aus der Josefstadt in die Welt. Landkarten aus dem 8ten. Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung im Bezirksmuseum Josefstadt, 9. März 2017 bis 20. Dezember 2017. Wien 2017, p. 92-122.

- Kremer, Aloys Sylvester: Darstellung des Steuerwesens, II. Theil. Wien 1821.

- Lego, Karl: Geschichte des Österreichischen Grundkatasters. Wien: BEV 1968.

- Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm: Sämtliche Schriften und Briefe. Hannover 2016. https://leibnizedition.de/.

- Lühning, Felix: "Wo aber bleiben wir Teutschen?" Johann Jakob Marinoni (Wien) und die Instrumentierung einer Sternwarte um 1720. In: Hamel, Jürgen (Hg.): Beiträge des Kolloquiums "Gottfried Kirch und die Berliner Astronomie im 18. Jahrhundert" in Berlin-Trepow am 6.3.2010. Frankfurt am Main: Harri Deutsch (Acta Historica Astronomiae, Vol. 41) 2010, p. 154-168.

- Marinoni, Giovanni Giacomo: De astronomia specula domestica et organico apparatu astronomico. Libri duo Reginæ Dicati a Joanne Jacobo Marinonio. Vienna: L.J. Kaliwoda 1745.

- Marinoni, Joannes Jacobus: De re ichnographica, cuius hodierna praxis exponitur et propriis exemplis pluribus illustratur in qua varias, quae contigere possunt, eiusdem aberrationes, posito quoque calculo, inquiritur. Vienna: Kaliwoda 1751.

- Marinoni, Joannes Jacobus: De re ichnometrica veteri et nova: recensentur experimenta per utramque habita, accedunt modi areas fundorum sine calculo investigandi. Vienna: Kaliwoda 1775.

- Marcello, Verga: Il "sogno spagnolo" di Carlo VI. Alcune considerazioni sulla monarchia asburgica e i domini italiani nella prima metà del Settecento. Bologna 1985.

- Oberhummer Eugen: Ein Jagdatlas Kaiser Karl VI. In: Unsere Heimat VI (1933), p. 152-159.

- Pärr, Nora: Wiener Astronomen -- ihre Tätigkeit an Privatobservatorien und Universitätssternwarten. Diplomarbeit an der Geisteswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Wien, 2001.

- Poggendorff, Johann Christian: Biographisch-literarisches Handwörterbuch zur Geschichte der exacten Wissenschaften, Band II. Leipzig: Johann Amrosius Barth 1863.

- Redlich, Oswald: "Weltmacht des Barock." Österreich in der Zeit Kaiser Leopolds I. Wien (4. Auflage) 1961.

- Schmeidler, Felix: Marinoni, Johann Jakob. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB), Band 16. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 1990.

- Seitschek, Stefan; Hutterer, Herbert & Gerald Theimer: 300 Jahre Karl VI. (1711--1740) -- Spuren der Herrschaft des "letzten" Habsburgers. Wien: Österreichisches Staatsarchiv 2011.

- Slezak, Friedrich: Johann Jakob Marinoni (1676-1755). In: Der Donauraum -- Zeitschrift für Donauforschung (1976), Nr. 21, p. 195-207.

- Sofonea, Traian: Johann Jakob von Marinoni (1676--1755) -- Sein Leben und Schaffen -- 300 Jahre nach seiner Geburt. In: ÖZ (1976), p. 97 ff.

- Steinmayr, Johann: Die alte Wiener Universitätssternwarte unter der Leitung von Jesuiten und Exjesuiten (1755--1816). In: Die Geschichte der Universitäts-Sternwarte Wien -- Vorträge von P.J. Steinmayer S.J. (1932). Siehe: Die Geschichte der Universitätssternwarte Wien: Dargestellt anhand ihrer historischen Instrumente und eines Typoskripts von Johann Steinmayr. Hg. von Hamel, Jürgen; Müller, Isolde & Thomas Posch. Frankfurt am Main (Acta Historica Astronomiae; 38) 2010.

- Virgin, Rosella: Giovanni Giacomo Marinoni (1676-1755). La nascita della cartografia moderna. Venedig: Tesi di Laurea, Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia 1998.

- Zinner, Ernst: Deutsche und niederländische astronomische Instrumente des 11.--18. Jahrhunderts. München: C.H. Beck 1956 (2. Auflage) 1967.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-31 17:02:28

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Anna Giulia Cavagna: MARINONI, Giovanni Giacomo, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 70 (2008).

- Liliana Cargnelutti: MARINONI GIOVANNI GIACOMO (1676--1755), matematico, cartografo

- Gian Giacomo Marinoni (Wikipedia, Furlan)

- Johann Jakob Marinoni (Wikipedia, German)

- Leander Anguissola, Johann Jacob Marinoni: Wien, 1704

- Correspondence of Matinoni (e manuscripta)

Links to external on-line pictures - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 18:32:58

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no information available

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 19:43:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude +48°12.7’ N, Longitude 16°21.7’ E, Elevation 180m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 18:32:57

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

-

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-31 16:12:15

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 1a. Marinoni’s private observatory ("De astronomica specula domestica et organico apparatu astronomico" (Wien: Kaliwoda 1745)

Giovanni Jacopo de Marinoni (1676--1755) and his Observatory

![Johann Jakob von [Giovanni Jacopo de] Marinoni (16](/images/astronomicalheritage.net/gallery/ahp_entities/entity000220/H+K_01.jpg)

Fig. 1b. Johann Jakob von [Giovanni Jacopo de] Marinoni (1676--1755), engraving by Ferdinand Landerer, undated (Bildarchiv der ÖNB, © ÖNB Wien, PORT_001211305_01AZ:27249/3/2017)

Fig. 1c. Coat of arms of Giovanni Jacopo de Marinoni (1676--1755) (Nobility Patent of Marinoni)

Giovanni Jacopo de [Johann Jakob] Marinoni (1676--1755) was born in Udine. In 1703, Emperor Leopold I gave him the title of court mathematician, which was confirmed by the following rulers Joseph I, Charles VI, and Maria Theresa until the end of his life.

The Imperial court mathematician erected in the 1720s in Vienna with Imperial support on the roof of his house on the Mölkerbastei (medieval bastion) a two-story tower, which he expanded to an observatory. This private observatory, which he describes in detail in his book, was actually the first observatory in Vienna.

Marinoni was knighted on April 9, 1733. Then, on April 22, 1733, Marinoni was appointed head of the Mathematical and Engineering Academy.

Founding of the first Polytechnical School in Central Europe

Fig. 2a. Patent of December 24, 1717 for the establishment of an engineering academy in Vienna under the direction of Anguissolas and the deputy director Marinoni (OeStA/KA ZSt HKR SR KzlA IV, 9. [© GZ: ÖSTA-2028656/0012-KA/2017])

Fig. 2b. Emperor Charles VI (1685--1740), painting by Johann Gottfried Auerbach (Museum of Military History, Vienna) (Wikipedia)

With an Imperial patent, dated December 24, 1717, Charles VI -- on recommendation Leander [Leandro] Anguissola (1653--1720) and Marinoni -- set up the first academy for military and civil engineers in the hereditary lands, later also known as the Mathematical and Engineering Academy, and appointed the proponents to be its directors (König 2017, p. 99 f).

Prince Eugene reports to Emperor Charles VI on May 17, 1718 that 45 students, including noble persons, philosophers and artists, were admitted and what progress they had made. Tuition was free, material expenses were low, but the salaries of the directors for part-time work were quite generous.

Marinoni as Cartographer and Court Mathematician

Fig. 3. The map of Vienna (1706) by Anguissola-Marinoni-Hildebrandt-Steinhausen (reprinted 1987) (https://1030wien.at/geschichte/historische-landkarten)

In 1704, Emperor Leopold I commissioned Anguissola and Marinoni to plan the line wall on the outer border of Vienna. In the same year, the famous Anguissola-Marinoni map of Vienna was created with the involvement of the court architect Lukas von Hildebrandt and the city engineer Arnold von Steinhausen (copper engraving 1706, reprint 1710), on which the fortifications are drawn. The inclusion of the suburbs in the truce and jurisdiction of the Imperial Capital and Residence City of Vienna by decree of July 15, 1689 resulted in the need for a city plan of the new, larger Vienna.

Marinoni is justifiably proud of the quality of its map renderings. The 300-year-old Milan cadastre (1719--1729, 16 large map sheets at a scale of 1:72,000) is the first cadastre to be drawn up based on the survey of an entire, contiguous country. In 1777, a copper-engraved map consisting of 9 sheets, reduced to a scale of 1:90,000, was created in Milan ("Carta Topografica dello Stato di Milano seconda la Misura Censuaria"). Marinoni is regarded as a model for the cadastral surveys of the 19th century.

Many of the maps and plans, which Marinoni created under the auspices of the Austrian Imperial family, have survived, and they not only represent a technical masterpiece, but are also priceless cultural assets of unsurpassed beauty. His two masterworks, describing his surveying activites, are "De re ichnographica" (Vienna 1751, Making maps and plans) and "De re ichnometrica" (Vienna 1775, The Surveying Technology).

Fig. 4a. Measuring table, invented by Johannes Prätorius [Johann Richter] (1537--1616), improved by Marinoni ("De re ichnographica" (1751), Graphic 24, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 771 q)

Fig. 4b. Measuring table, invented by Johannes Prätorius [Johann Richter] (1537--1616), improved by Marinoni ("De re ichnographica" (1751), Graphic 11, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 771 q)

When surveying Vienna, Marinoni used the measuring table, invented by Johannes Prätorius [Johann Richter] (1537--1616), professor of the Nuremberg University in Altdorf. But Marinoni had improved it by fitting a larger table on the top and he used a more stable tripod. Since then, he has used this new measuring table regularly and made constant efforts to perfect it. Finally, in 1714, he constructed the final version with which he carried out the cadastral survey of Milan. His improvements to the measuring table, consisted in enlarging the diopter ruler and also attaching a mountain diopter to it for strongly inclined sights, and he also designed a circular and a linear displacement option for the table top in two mutually perpendicular directions in order to be able to precisely adjust the measuring table over the position.

Fig. 4c. Application of the Planimetric Balance for area determination and production of standardized foils (Marinoni: "De re ichnometrica" (1775), frontispice, Tab. I, p. 231, Tab. IV, p. 239, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 1072 q)

Marinoni as Astronomer

Fig. 5a. The house of the court mathematician Marinoni on the Mölkerbastei with the astronomical observation tower (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, p. 1, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 5b. Some of Marinoni’s astronomical instruments (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 5c. Frontispice of Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745 (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Marinoni had the first observatory in Vienna set up in his private home on the Mölkerbastei in the 1720s, for which he had the most modern observation instruments, purchased at the Emperor’s expense, as he wrote in 1745 in his book De astronomica specula domestica et organico apparatu astronomico libri duo Reginae dicati a Joanne Jacobo Marinonio patricio utinensi, etc. described. In the dedication of De astronomica specula to Maria Theresa, Marinoni first praises the generous support of her late father Charles VI. for its observatory.

Due to the heights of the Vienna Woods (Wiener Wald), the Marinonis Observatory only had lack of horizon view, with the result that rising and setting points of the celestial bodies were often not precisely ascertainable, and there was also fog from the Danube lowlands.

The house is also rotated 45° from the meridian. Marinoni therefore concentrated on positional and transit astronomy, observations of the corresponding altitudes in order to precisely determine the meridian, culmination observations and tracking the Jupiter satellites.

In the description of his observatory in "De astronomica specula domestica", sections of the building illustrate the high windows, the wooden roof beams, the narrow gallery with the iron handrail and the observation pendulum clock.

On the roof of the astronomical tower, there was a weather vane in the form of a rooster, which was also Marinoni’s heraldic animal, connected by a vertical shaft to a pointer that showed the wind direction on a compass rose on the ceiling of the main room of the observatory, which could be read without having to go outside.

Fig. 6a. Astronomical observation tower on Marinoni’s house on the Mölkerbastei, with astronomical instruments (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, Tab. II (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 6b. Astronomical observation tower on Marinoni’s house on the Mölkerbastei, with astronomical instruments, with a weather vane (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, Tab. IV (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 6c. Marinoni’s Observatory on the Mölkerbastei with a weather vane (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, Tab. III (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 6d. Weather vane of Marinoni’s Observatory (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber I, Tab. III (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

The telescope for transit observations of fixed stars is notable for its extraordinarily stable and meticulous design, which gives Marinoni good marks as an engineer. Marinoni also constructed entirely new quadrants for the southern and northern meridian. In addition to the built-in instruments, Marinoni also had portable devices for astronomical purposes, and geodetic instruments.

The exact clocks made in London, Paris and Vienna were also of great importance. In particular, the pendulum clock from Paris was a special "equatorial clock" which, in addition to the mean solar time, also displayed the true solar time by means of a own scale. This scale was controlled by a cam disk, which took into account the difference between mean and true solar time of up to approx. ±16 minutes (Equation of Time).

Altogether Marinoni describes 19 instruments: 2 heavy, iron meridian mural quadrants, 1 transit instrument, 3 pendulum clocks, 5 larger transportable quadrants, 4 smaller transportable goniometers, 6 telescopes, 1 celestial globe with a diameter of 24-inch = 63.2cm, made by Joan Blaeu (1596--1673).

The instruments were equipped with the best screw or thread micrometers. The richness and quality of the furnishings can be explained by the fact that the emperor paid quite a bit for the training of his engineers, officers and master builders.

Fig. 7a. "Mercurius transiens per discum Solis in eoque culminans Viennae Austriae, the 11 novembris Anno: 1736" (Biblioteca comunale Udine, Sign. Misc. 36 32, 1/5472)

Fig. 7b. "Report about the Mercury transit in Vienna (1736) from «Mémoires pour l’histoire des sciences et des beaux-arts» (1738), p. 99 f (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k30670d/f98.item.zoom)

The description of his observatory made Marinoni famous throughout Europe and he corresponded with all the luminaries of his time. Marinoni observed the Mercury transit in Vienna on November 11, 1736. His observation report "Mercurius transiens per discum Solis" was published in 1738 in the monthly journal Mémoires pour l’histoire des sciences et des beaux-arts.

Marinoni’s passion for astronomy and new technology makes his observatory and library a magnet for scholars visiting Vienna and mentions that e.g. Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis, Giuseppe Bini, Apostolo Zeno, Maffei, Florio and Rolandi visited the private observatory. Leonhard Euler asked Marinoni to transmit further moon observations.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 7

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-31 17:05:05

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 8a. Parisian equatorial clock by Alexandre Le Faucheur, in which the position of an additional scale was controlled by a cam disc in order to also display true solar time ("mechanical sundial"); on the dial above XII is inscribed: "Temporis Aequalitas"; Time displayed (mean solar time): 2h53m29s (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber II, p. 186 (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 8b. Parisian equatorial clock by Alexandre Le Faucheur, artistically designed (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber II, p. 191 (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Instruments

- Southern and Northern heavy iron meridian mural quadrants

- Transit instrument

- 3 pendulum clocks, made in London, Paris and Vienna

- 5 larger transportable quadrants

- 4 smaller transportable goniometers

- 6 telescopes

- Celestial globe with a diameter of 24-inch = 63.2cm, made by Joan Blaeu (1596--1673).

Fig. 9a. Map of Vienna, where the Marinonis observatory on the Mölkerbastei (Spec. dom. a) and the observatory of the Jesuit College (Spec. SJ) near the Dominican bastion are marked (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Fig. 9b. Southern mural quadrant and geodetic instruments (Marinoni: De astronomica specula domestica, 1745, Liber II, Tab. I after p. 78 and Tab. IX after p. 114 (ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 8917 q)

Marinoni’s Scientific Achievements

Giovanni Giacomo Marinoni’s merits are: He was appointed as court mathematician (1703), director of the Mathematical and Engineering Academy (1717), one of the first Polytechnical Schools in Europe, in addition, he was cartographer of Vienna (Anguissola-Marinoni map of Vienna, 1704) and of Milan (cadastral land register, 1719--1729), and published surveying books: "De re ichnographica" (Vienna 1751) and "De re ichnometrica" (Vienna 1775).

As astronomer, Marinoni published De astronomica specula domestica (1745) with a detailed description of his private observatory on Mölkerbastei, sponsered by the Imperial court, and of his collection of astronomical and geodetical instruments. He was active in positional and transit astronomy, observations of the Jupiter satellites, and the Transit of Mercury (1736), published as "Mercurius transiens per discum Solis" (1738).Marinoni had good contacts to famous astronomers all over Europe (Hiermanseder & König, 2020) and corresponded with e.g. Leonhard Euler (1707--1783), Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz (1646--1716), Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (1698--1759), Joseph-Nicolas Delisle (1688--1768), Christfried Kirch (1694--1740) oder Sámuel Mikovíny (1686/98--1750). Marinoni was external member of the Royal Prussian Society of Sciences (1746), and honorary member of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg (1746).

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-31 16:16:12

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 10. Pasqualati house (1797), built on the ramp of the former town fortifications (Mölker bastion), view from Universitätsring around 1904-1905 (Photograph by August Stauda, Wien Museum, Inv.-Nr. 29468; CC0 licence)

The Marinoni Observatory (Mölkerbastei 8) is no longer existing.

It is replaced by the Pasqualati house (1797), built on the ramp of the former town fortifications (Mölker bastion). The architect was Peter Mollner (1732--1801), who erected the Pasqualati house for Empress Maria Theresa’s personal physician, Joseph Benedikt, Baron Pasqualati von Osterberg (1733--1799); it was a residence of Ludwig van Beethoven between 1804 and 1814.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 19:40:50

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Marinoni Observatory (Mölkerbastei 8) is built on the former town fortifications; other examples of observatories on fortifications: Nuremberg Castle Eimmart’s Observatory (1678--1757), Oude Sterrewacht Leiden (1633--1860) and Sonnenborgh Observatory Utrecht (1853, now museum) observatories.

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 19:28:16

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The Marinoni Observatory is no longer existing.

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-30 18:32:57

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no information available

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-31 16:17:35

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

No astronomical relevance today, but Marinoni’s publications show his merits in astronomy and cartography.

Fig. 11a. Frontispiece of Marinoni’s book "De re ichnographica" (1751), Marinoni, inspired by "Mathematica", led out into the landscape in order to take measurements (Quelle: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 771 q)

Fig. 11b. Marinoni’s book "De re ichnographica" (1751), like in the book from 1745, the map of Vienna is shown on the title page (Quelle: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 771 q)

Fig. 11c. Frontispiece of Marinoni’s book "De re ichnographica" (Wien 1775) (Quelle: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 1072 q)

Fig. 11d. Title page with city map of Milan (Mediolanum) of Marinoni’s book "De re ichnographica" (Wien 1775) (Quelle: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Sign.: Rar 1072 q)

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 220

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-04-10 16:26:48

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Anguissola, Leandro & Giovanni Giacomo Marinoni: Accuratissima Viennae Austriae ichnographica delineatio. Vienna: inc. J.A. Pfeiffel & C. Englebrecht 1706.

- Bortolan, Pirona Eugenio: Vita e opere di Gian Giacomo Marinoni. In: Marinoni Istituto Tecnico Statale per Geometri 1961--2011. 50 anni dalla Fondazione. Udine 2012.

- Bredekamp, Horst & Wladimir Velminski (Hg.): Mathesis & Graphé: Leonhard Euler und die Entfaltung der Wissenssysteme. Berlin: Akademie 2010.

- Candiloro Ignazio: Giovanni Giacomo Marinoni matematico, topografo e astronomo udinese. In: L’Universo 52 (1972), 2, p. 428-438.

- Cargnelutti, Liliana: Marinoni. sine anno, cf. http://www.dizionariobiograficodeifriulani.it/marinoni-giovanni-giacomo/.

- Cavagna, Anna Giulia: I libri di Giovanni Giacomo Marinoni. In: Gli spazi del libro nell’Europa del XVIII secolo, a cura di Maria Gioia Tavoni e Françoise Waquet. Bologna: Pàtron 1997, p. 129-152.

- Cavagna, Anna Giulia: Opere e libri di un astronomo cartografo del XVIII secolo: tra erudizione e Stato. In: Nuncius - Annali di storia della scienza XIII (1998), fasc. 2, p. 461-491.

http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/182539198x00509. - Cavagna, Anna Giulia: A Free Transmission of Knowledge: The Literary Gifts and Reception of an Eighteenth-Century Scholar. In: Printing for Free: Non Commercial Publishing in Commercial Societies. Edited by James Raven. Burlington, USA: Ashgate 2000, p. 29-47.

- Cavagna, Anna Giulia: Marinoni, Giovanni Giacomo. In: Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 70. Rom 2008, p. 425-445.

- Gatti, Bertram: Prinz Eugen und die Ingenieur-Akademie. In: Oesterreichische militärische Zeitschrift (1866), Bd. I.

- Gatti, Friedrich: Geschichte der K.K. Ingenieur- und K.K. Genie-Akademie, 1717--1869. Wien 1901.

- Fox, Dirk & Thomas Püttmann: Technikgeschichte mit fischertechnik. Heidelberg 2015.

- Hanne, Egghardt: Prinz Eugen, der Philosoph in Kriegsrüstung. Facetten einer außergewöhnlichen Persönlichkeit. Wien: Kremayr & Scheriau 2013.

- Hiermanseder Michael: Wie sich die Bilder gleichen! Der Mailänder Kataster von 1718 als Vorbild für die preußische Katastervermessung im Herzogtum Magdeburg 1720. In: Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) 4 (2017), p. 235 ff.

- Hiermanseder Michael: Aus der Korrespondenz von Johann Jakob von Marinoni mit Leonhard Euler 1736--1751 "... quasdam meditationes Tecumque communicare, quas ut benevole accipias, Tuumque de iis judicium perscribas, etiam atque etiam rogo." From the correspondence of Jacopo de Marinoni with Leonhard Euler 1736--1751 "... and to share some considerations with you, so that you receive them benevolently, and write down your judgement about them, I ask you again." In: Vermessung & Geoinformation 2 (2018) and 4 (2018), p. 264--305.

- Hiermanseder, Michael & Heinz König: Johann Jakob von Marinoni -- geadelt und getadelt. Schöpfer des Mailänder Katasters, Kartograph, Wissenschaftler. In: Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) 2 (2017), p. 60 ff.

- Hiermanseder, Michael & Heinz König: Johann Jakob von Marinoni und der Mailänder Kataster von 1718. In: DVW-Bayern 2 (2018), p. 145--167.

- Hiermanseder, Michael & Heinz König: Johann Jakob von Marinoni -- Mathematiker, Astronom, Geodät -- Internationale Kontakte eines Wissenschaftlers im Wien des 18. Jahrhunderts. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Internationalität in der astronomischen Forschung (18. bis 21. Jahrhundert). Internationality in the Astronomical Research (18th to 21st Century). Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Wien 2018. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis; Vol. 49) 2020, p. 150--195.

- Hiermanseder, Michael, private communication (2022).

- König, Heinz: Der Vermesser, Mathematiker und Astronom Johann Jakob Marinoni und die Josefstadt. In: Aus der Josefstadt in die Welt. Landkarten aus dem 8ten. Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung im Bezirksmuseum Josefstadt, 9. März 2017 bis 20. Dezember 2017. Wien 2017, p. 92-122.

- Kremer, Aloys Sylvester: Darstellung des Steuerwesens, II. Theil. Wien 1821.

- Lego, Karl: Geschichte des Österreichischen Grundkatasters. Wien: BEV 1968.

- Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm: Sämtliche Schriften und Briefe. Hannover 2016. https://leibnizedition.de/.

- Lühning, Felix: "Wo aber bleiben wir Teutschen?" Johann Jakob Marinoni (Wien) und die Instrumentierung einer Sternwarte um 1720. In: Hamel, Jürgen (Hg.): Beiträge des Kolloquiums "Gottfried Kirch und die Berliner Astronomie im 18. Jahrhundert" in Berlin-Trepow am 6.3.2010. Frankfurt am Main: Harri Deutsch (Acta Historica Astronomiae, Vol. 41) 2010, p. 154-168.

- Marinoni, Giovanni Giacomo: De astronomia specula domestica et organico apparatu astronomico. Libri duo Reginæ Dicati a Joanne Jacobo Marinonio. Vienna: L.J. Kaliwoda 1745.

- Marinoni, Joannes Jacobus: De re ichnographica, cuius hodierna praxis exponitur et propriis exemplis pluribus illustratur in qua varias, quae contigere possunt, eiusdem aberrationes, posito quoque calculo, inquiritur. Vienna: Kaliwoda 1751.

- Marinoni, Joannes Jacobus: De re ichnometrica veteri et nova: recensentur experimenta per utramque habita, accedunt modi areas fundorum sine calculo investigandi. Vienna: Kaliwoda 1775.