Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Asakusa Astronomical Observatory, Taito City, Tokyo, Japan

Format: IAU - Outstanding Astronomical Heritage

Description

Geographical position - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 01:45:59

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Asakusa Astronomical Observatory,

3 Chome-20-12 Asakusabashi, Taito City, Tokyo 111-0053, Japan

(1782 to 1869), (East-of-Torikoe-Shrine) -- Historical landmark

Location - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-10 18:36:00

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude 35.701442° N, Longitude 139.788798° E, Elevation ...m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-10 18:23:49

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

-

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 10

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-13 19:23:36

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

![Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799), (www.g](/images/astronomicalheritage.net/gallery/ahp_entities/entity000248/ASADA-Goryu-1734-1799.png)

Fig. 1a. Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799), (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

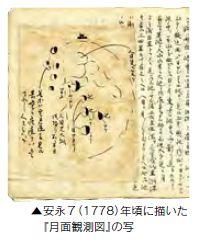

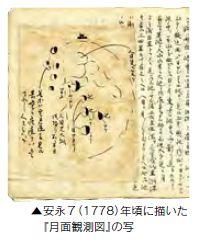

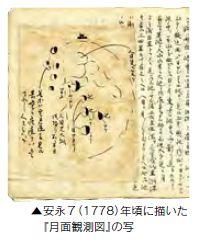

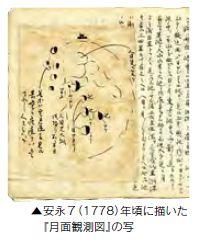

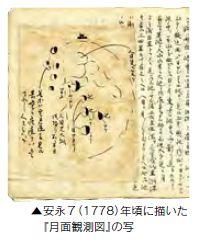

Fig. 1b. Gōryū ASADA’s calculations -- Japan’s oldest lunar observation map (Stadtbibliothek Kitsuki)

Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799)

Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799) was a Japanese astronomer and anatomist / Confucian physician. In addition to his work as a physician of his fief, his liege lord, since 1767, ASADA initially dealt with creating calendars. The Japanese Imperial year is based on the date of the legendary founding Emperor Jimmu in 660 BC.

In 1772, he fled to Osaka, changed his surname from AYABE to ASADA, where he resumed the study of astronomy, making his living by practicing medicine.

The official astronomers missed to predict the solar eclipse of Oct 07, 1763. ASADA calculated and predicted the solar eclipse for the New Year’s Day 1786 (Gregorian Calendar January 30, 1786), published as "Records Based on Observations", which suddenly made his name known to the Japanese government.

In Osaka ASADA founded the Senjikan School of Astronomy, an important school of calendrical scientists. One of his students was the wealthy merchant Shigetomi HAZAMA (1756--1816), another the later astronomer Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI since 1787. ASADA grounded optical lenses and constructed telescopes, with which he observed the moons of Jupiter or craters on the moon. In addition, he measured the Sun’s rotation by observing sunspots.

Due to the Japanese policy of isolation at the time, Western scientific knowledge only reached the island in the form of outdated Chinese works which had been translated by Jesuit missionaries in China.

Based on the first volume of the Chinese Li-hsiang k’ao-ch’eng ("Compendium of Calendrical Science", 1713) -- essentially Tychonian astronomy, which was his source for studying Western astronomy, ASADA determined the ephemerides, the positions of the Sun and the Moon, and calculated solar and lunar eclipses.

He developed methods for determining the orbits of the celestial bodies of the solar system, studying the theory of the elliptic orbit, and independently confirmed Kepler’s third law. In addition, he is credited for discovery of the socalled Sho-Cho (Hsiao-ch’ang) law, dealing with the variability in the length of the tropical year -- basis for an accurate calendar.

In 1795, the Shogunate proposed to reform the current Japanese calendar, the Horyaku Reki calendar, by using the new theories of Western astronomy. ASADA proposed -- due to his poor health -- not to appoint himself as the official astronomer, but his distinguished scholar Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI and to choose HAZAMA as an assistant. This led to the Kansei Calendar in 1797, the first based on Westen principles.

In praise of Gōryū ASADA, TAKAHASHI stated in his Zōshū shōchō hō:

"Laboring over Chinese and Western works, Asada Goryu at Osaka discovered the shocho law. Although Western astronomy is most advanced, we have not heard of its mentioning this law, known only in our country. Therefore I have said that although we are unable to boast about our achievements in comparison with those of the Westerners, my country should be proud of this man and his discovery." (World Biographical Encyclopedia)

ASADA had modernized astronomy in Japan and introduced modern astronomical instruments and methods of observation, influenced by the Western culture and science.

His numerous achievements have been recognized by naming a lunar crater "Crater Asada".

Fig. 2a. Grave of Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804), (CC3, Nekosuki600)

Fig. 2b. Monument for the cartographer Tadataka INŌ (1745--1818) in Sawara Katori City, (CC2.5, katorisi)

Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804) and Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829)

Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804), born in Osaka, was appointed official astronomer by the shogunate in 1795. Together with the astronomer ASADA and Shigetomi HAZAMA (1756--1816), he developed the Kansei Calendar, a Japanese lunisolar calendar, which was officially introduced in 1797.

TAKAHASHI translated a Dutch version of Joseph Lalande’s (1732--1807) Traité d’astronomie entitled "Lalande Calendar, Summary", 11 volumes (1803), 8 of which survived. His assistant was his son Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829), who succeeded him in 1804.

Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829), astronomer and cartographer, published in 1810 by order of the Bakufu a modern world map entitled "Reworked Map of the Whole World with All Countries". He continued by making an accurate map of Japan based on the surveys of the cartographer Tadataka INŌ (1745--1818), who became his scholar despite of being 19 years older.

Fig. 3a. Edo city map (1844/47), (CC)

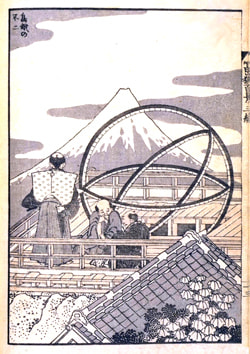

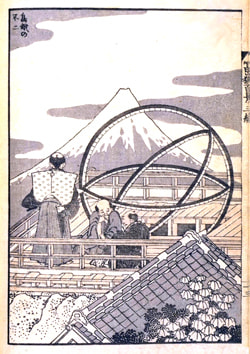

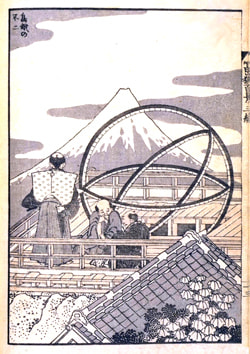

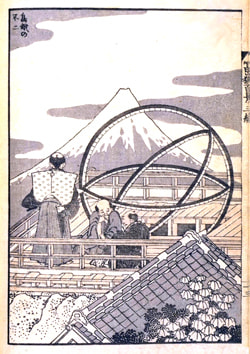

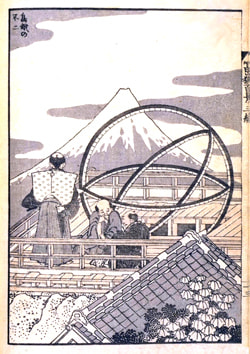

Fig. 3b. Torigoe no Fuji Observatory of the Calendar Bureau, One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, artist Katsushika HOKUSAI (1834-35), (CC)

Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory in Asakusa (1782--1869)

In the late Edo era (in the time of the Tokugawa Shōgunat, 1603 to 1868), the Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory in Asakusa, East of the Torikoe Shrine (Asakusa-ku from 1878 to 1947, then changed to "Taito Ward"), in the North-East of Edo (today Tokyo) was founded in 1782/95 by Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI.

The Tenmonkata (Official Astronomer) worked and made observations under the direction of the Shogun. Timekeeping and calendar making were the main tasks of the astronomers; the astronomical office where calendars were compiled, was called Hanreki-sho Goyo Yashiki or Asakusa Tenmondai. The solar Gregorian Calendar was first introduced in 1873 as part of the Japan’s Meiji period modernization.

In addition, surveying lands, compiling geographical descriptions and translating Western books played an important role.

The Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory existed until 1869 in Taito City (former Asakusa) in Tokyo and disappeared after the Meiji Restoration (1868), when Mutsuhito Emperor MEIJI (1852--1912) became the 122. Tenno of Japan.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-13 19:18:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

In the Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science one can find an impressive collection of telescopes, instruments, globes and clocks:

Fig. 4a. Armillary sphere made of bronze, (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 4b. Quadrant (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Instruments, Telescopes, and Clocks

- Large Armillary Sphere -- the artist Katsushika HOKUSAI (1760--1849) created a famous woodblock print series One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, Torikoe no Fuji. One painting shows the astronomical observatory against a backdrop of Mt. Fuji, which was seen from Torikoe Shrine.

- Quadrant, medium-size quadrant with a radius of approximately 115cm, created by Shigetomi HAZAMA, a teacher of Tadataka INO, referring to "Reidai Gishoshi" (written by Ferdinand Verbiest in 1674), used for surveying.

- Quadrant, large quadrant with a radius of approximately 182cm

- Map making tools of the surveyor and cartographer Tadataka INO (1745--1818)

- Japanese Terrestrial Globe (18th century)

The map on the globe is based on the world map created by the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci. In Japan, the first terrestrial and celestial globes were created by Shunkai Shibukawa, an official astronomer of the shogunate, in 1690.

- Celestial Globe (1855)

This celestial globe is based on "Gisho Kosei" published in 1752, which adopted Western astronomy. But normally Japanese astronomy in the Edo era was influenced by Chinese astronomy, which used constellations typical in China. It is interesting that daily positions of Comet Donati (1858) are marked.

- Telescopes of the Edo Period

- Japanese clocks: small pillow clocks, bracket clocks, portable clocks used in front of lanterns, hanging bell shaped clocks

- Pillar Clocks

- Drum Clocks

- Double balance large pedestal clock: This large clock has a mechanism made of iron, a sun hand, a lunar phase display, an alarm function with four legs.

- 20-cm-Equatorial Refracting Telescope, made by Troughton & Simms, imported by the Meiji Government in 1880.

Fig. 5a. Reflecting telescope (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 5b. Wadokei Japonese Clock à-double-foliot, Edo era, Le Musée Paul Dupuy (CC4, Didier Descouens)

Historical books:

Heitengi Zukai (1802)

"Heitengi Zukai", a handbook of astronomy, was written by Zenbe Iwasaki, who was also a maker of telescopes.

The Astronomical Herald, vol. 3 (1910)

"The Astronomical Herald" is a journal of the Astronomical Society of Japan, founded in 1908. The book contains observations of Halley’s Comet (1910).

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:29:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6. Ruins of the Astronomical Observatory (1782-1869) in Asakusa (credit: Taito City)

The Astronomical Observatory in Edo-Asakusa (1782) existed only until 1869, now there are ruins (Tokio-Taito City).

But a good collection of astronomical instruments is preserved in the Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:30:41

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Hockey, Thomas: Asada Goryu (1734--1799). In: The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer Publishing 2007.

- Keene, D.: The Japanese Discovery of Europe, 1720--1830. Stanford University Press 1969, p. 152.

- Lane, Richard: Hokusai: Life and Work. E.P. Dutton 1989.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: A History of Japanese Astronomy: Chinese Background and Western Impact. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press 1969.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: "Asada Goryu". In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons 1970, p. 310-314.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: Japanese Scientific Thought. In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 15 (Suppl. 1). Edited by Charles Coulston Gillispie. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, p. 728-758.

- Sugimoto, Masayoshi & David L. Swain: Science and Culture in Traditional Japan. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle and Co. 1989.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Ino Tadataka. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 608.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Takahashi Kageyasu. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 1506.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Takahashi Yoshitoki. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 1507.

- Otani, Ryokichi: Tadataka Ino: The Japanese Land-Surveyor. Simon Publications 2001, p. 33 ff.

- Shinkai, Hisaaki: Goryu Asada and Kepler’s third law of planetary motion. In: Kyoto University (Hg.): Memoirs of Osaka Institute of Technology, Band 61, Nr. 2. Osaka 2016, p. 27-36.

- Renshaw, Steven L. & Saori Ihara: Asada, Goryu. In: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer 2007, p. 64-65.

- Renshaw, Steven L.: Asada, Goryu. In: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer 2014, p. 110-111.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:32:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Asada Goryu (Wikipedia)

- World Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Springer)

- Barley shochu GORYU [Oita’s second man] About Goryu Asada

- Takahashi Yoshitoki (Wikipedia)

- Takahashi Kageyasu (Wikipedia)

- Ino Tadataka (1745--1818) (Wikipedia)

- Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science, Admiring Scientists’ Unquenchable Spirit of Inquiry in the Edo Period

Links to external on-line pictures - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-10 18:23:51

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no information available

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 01:45:59

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Asakusa Astronomical Observatory,

3 Chome-20-12 Asakusabashi, Taito City, Tokyo 111-0053, Japan

(1782 to 1869), (East-of-Torikoe-Shrine) -- Historical landmark

Location - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-10 18:36:00

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude 35.701442° N, Longitude 139.788798° E, Elevation ...m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-10 18:23:49

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

-

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 10

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-13 19:23:36

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

![Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799), (www.g](/images/astronomicalheritage.net/gallery/ahp_entities/entity000248/ASADA-Goryu-1734-1799.png)

Fig. 1a. Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799), (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 1b. Gōryū ASADA’s calculations -- Japan’s oldest lunar observation map (Stadtbibliothek Kitsuki)

Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799)

Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799) was a Japanese astronomer and anatomist / Confucian physician. In addition to his work as a physician of his fief, his liege lord, since 1767, ASADA initially dealt with creating calendars. The Japanese Imperial year is based on the date of the legendary founding Emperor Jimmu in 660 BC.

In 1772, he fled to Osaka, changed his surname from AYABE to ASADA, where he resumed the study of astronomy, making his living by practicing medicine.

The official astronomers missed to predict the solar eclipse of Oct 07, 1763. ASADA calculated and predicted the solar eclipse for the New Year’s Day 1786 (Gregorian Calendar January 30, 1786), published as "Records Based on Observations", which suddenly made his name known to the Japanese government.

In Osaka ASADA founded the Senjikan School of Astronomy, an important school of calendrical scientists. One of his students was the wealthy merchant Shigetomi HAZAMA (1756--1816), another the later astronomer Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI since 1787. ASADA grounded optical lenses and constructed telescopes, with which he observed the moons of Jupiter or craters on the moon. In addition, he measured the Sun’s rotation by observing sunspots.

Due to the Japanese policy of isolation at the time, Western scientific knowledge only reached the island in the form of outdated Chinese works which had been translated by Jesuit missionaries in China.

Based on the first volume of the Chinese Li-hsiang k’ao-ch’eng ("Compendium of Calendrical Science", 1713) -- essentially Tychonian astronomy, which was his source for studying Western astronomy, ASADA determined the ephemerides, the positions of the Sun and the Moon, and calculated solar and lunar eclipses.

He developed methods for determining the orbits of the celestial bodies of the solar system, studying the theory of the elliptic orbit, and independently confirmed Kepler’s third law. In addition, he is credited for discovery of the socalled Sho-Cho (Hsiao-ch’ang) law, dealing with the variability in the length of the tropical year -- basis for an accurate calendar.

In 1795, the Shogunate proposed to reform the current Japanese calendar, the Horyaku Reki calendar, by using the new theories of Western astronomy. ASADA proposed -- due to his poor health -- not to appoint himself as the official astronomer, but his distinguished scholar Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI and to choose HAZAMA as an assistant. This led to the Kansei Calendar in 1797, the first based on Westen principles.

In praise of Gōryū ASADA, TAKAHASHI stated in his Zōshū shōchō hō:

"Laboring over Chinese and Western works, Asada Goryu at Osaka discovered the shocho law. Although Western astronomy is most advanced, we have not heard of its mentioning this law, known only in our country. Therefore I have said that although we are unable to boast about our achievements in comparison with those of the Westerners, my country should be proud of this man and his discovery." (World Biographical Encyclopedia)

ASADA had modernized astronomy in Japan and introduced modern astronomical instruments and methods of observation, influenced by the Western culture and science.

His numerous achievements have been recognized by naming a lunar crater "Crater Asada".

Fig. 2a. Grave of Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804), (CC3, Nekosuki600)

Fig. 2b. Monument for the cartographer Tadataka INŌ (1745--1818) in Sawara Katori City, (CC2.5, katorisi)

Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804) and Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829)

Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804), born in Osaka, was appointed official astronomer by the shogunate in 1795. Together with the astronomer ASADA and Shigetomi HAZAMA (1756--1816), he developed the Kansei Calendar, a Japanese lunisolar calendar, which was officially introduced in 1797.

TAKAHASHI translated a Dutch version of Joseph Lalande’s (1732--1807) Traité d’astronomie entitled "Lalande Calendar, Summary", 11 volumes (1803), 8 of which survived. His assistant was his son Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829), who succeeded him in 1804.

Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829), astronomer and cartographer, published in 1810 by order of the Bakufu a modern world map entitled "Reworked Map of the Whole World with All Countries". He continued by making an accurate map of Japan based on the surveys of the cartographer Tadataka INŌ (1745--1818), who became his scholar despite of being 19 years older.

Fig. 3a. Edo city map (1844/47), (CC)

Fig. 3b. Torigoe no Fuji Observatory of the Calendar Bureau, One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, artist Katsushika HOKUSAI (1834-35), (CC)

Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory in Asakusa (1782--1869)

In the late Edo era (in the time of the Tokugawa Shōgunat, 1603 to 1868), the Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory in Asakusa, East of the Torikoe Shrine (Asakusa-ku from 1878 to 1947, then changed to "Taito Ward"), in the North-East of Edo (today Tokyo) was founded in 1782/95 by Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI.

The Tenmonkata (Official Astronomer) worked and made observations under the direction of the Shogun. Timekeeping and calendar making were the main tasks of the astronomers; the astronomical office where calendars were compiled, was called Hanreki-sho Goyo Yashiki or Asakusa Tenmondai. The solar Gregorian Calendar was first introduced in 1873 as part of the Japan’s Meiji period modernization.

In addition, surveying lands, compiling geographical descriptions and translating Western books played an important role.

The Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory existed until 1869 in Taito City (former Asakusa) in Tokyo and disappeared after the Meiji Restoration (1868), when Mutsuhito Emperor MEIJI (1852--1912) became the 122. Tenno of Japan.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-13 19:18:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

In the Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science one can find an impressive collection of telescopes, instruments, globes and clocks:

Fig. 4a. Armillary sphere made of bronze, (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 4b. Quadrant (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Instruments, Telescopes, and Clocks

- Large Armillary Sphere -- the artist Katsushika HOKUSAI (1760--1849) created a famous woodblock print series One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, Torikoe no Fuji. One painting shows the astronomical observatory against a backdrop of Mt. Fuji, which was seen from Torikoe Shrine.

- Quadrant, medium-size quadrant with a radius of approximately 115cm, created by Shigetomi HAZAMA, a teacher of Tadataka INO, referring to "Reidai Gishoshi" (written by Ferdinand Verbiest in 1674), used for surveying.

- Quadrant, large quadrant with a radius of approximately 182cm

- Map making tools of the surveyor and cartographer Tadataka INO (1745--1818)

- Japanese Terrestrial Globe (18th century)

The map on the globe is based on the world map created by the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci. In Japan, the first terrestrial and celestial globes were created by Shunkai Shibukawa, an official astronomer of the shogunate, in 1690.

- Celestial Globe (1855)

This celestial globe is based on "Gisho Kosei" published in 1752, which adopted Western astronomy. But normally Japanese astronomy in the Edo era was influenced by Chinese astronomy, which used constellations typical in China. It is interesting that daily positions of Comet Donati (1858) are marked.

- Telescopes of the Edo Period

- Japanese clocks: small pillow clocks, bracket clocks, portable clocks used in front of lanterns, hanging bell shaped clocks

- Pillar Clocks

- Drum Clocks

- Double balance large pedestal clock: This large clock has a mechanism made of iron, a sun hand, a lunar phase display, an alarm function with four legs.

- 20-cm-Equatorial Refracting Telescope, made by Troughton & Simms, imported by the Meiji Government in 1880.

Fig. 5a. Reflecting telescope (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 5b. Wadokei Japonese Clock à-double-foliot, Edo era, Le Musée Paul Dupuy (CC4, Didier Descouens)

Historical books:

Heitengi Zukai (1802)

"Heitengi Zukai", a handbook of astronomy, was written by Zenbe Iwasaki, who was also a maker of telescopes.

The Astronomical Herald, vol. 3 (1910)

"The Astronomical Herald" is a journal of the Astronomical Society of Japan, founded in 1908. The book contains observations of Halley’s Comet (1910).

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:29:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6. Ruins of the Astronomical Observatory (1782-1869) in Asakusa (credit: Taito City)

The Astronomical Observatory in Edo-Asakusa (1782) existed only until 1869, now there are ruins (Tokio-Taito City).

But a good collection of astronomical instruments is preserved in the Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:30:41

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Hockey, Thomas: Asada Goryu (1734--1799). In: The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer Publishing 2007.

- Keene, D.: The Japanese Discovery of Europe, 1720--1830. Stanford University Press 1969, p. 152.

- Lane, Richard: Hokusai: Life and Work. E.P. Dutton 1989.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: A History of Japanese Astronomy: Chinese Background and Western Impact. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press 1969.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: "Asada Goryu". In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons 1970, p. 310-314.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: Japanese Scientific Thought. In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 15 (Suppl. 1). Edited by Charles Coulston Gillispie. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, p. 728-758.

- Sugimoto, Masayoshi & David L. Swain: Science and Culture in Traditional Japan. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle and Co. 1989.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Ino Tadataka. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 608.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Takahashi Kageyasu. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 1506.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Takahashi Yoshitoki. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 1507.

- Otani, Ryokichi: Tadataka Ino: The Japanese Land-Surveyor. Simon Publications 2001, p. 33 ff.

- Shinkai, Hisaaki: Goryu Asada and Kepler’s third law of planetary motion. In: Kyoto University (Hg.): Memoirs of Osaka Institute of Technology, Band 61, Nr. 2. Osaka 2016, p. 27-36.

- Renshaw, Steven L. & Saori Ihara: Asada, Goryu. In: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer 2007, p. 64-65.

- Renshaw, Steven L.: Asada, Goryu. In: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer 2014, p. 110-111.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:32:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Asada Goryu (Wikipedia)

- World Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Springer)

- Barley shochu GORYU [Oita’s second man] About Goryu Asada

- Takahashi Yoshitoki (Wikipedia)

- Takahashi Kageyasu (Wikipedia)

- Ino Tadataka (1745--1818) (Wikipedia)

- Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science, Admiring Scientists’ Unquenchable Spirit of Inquiry in the Edo Period

Links to external on-line pictures - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-10 18:23:51

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no information available

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-10 18:36:00

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude 35.701442° N, Longitude 139.788798° E, Elevation ...m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-10 18:23:49

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

-

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 10

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-13 19:23:36

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

![Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799), (www.g](/images/astronomicalheritage.net/gallery/ahp_entities/entity000248/ASADA-Goryu-1734-1799.png)

Fig. 1a. Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799), (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 1b. Gōryū ASADA’s calculations -- Japan’s oldest lunar observation map (Stadtbibliothek Kitsuki)

Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799)

Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799) was a Japanese astronomer and anatomist / Confucian physician. In addition to his work as a physician of his fief, his liege lord, since 1767, ASADA initially dealt with creating calendars. The Japanese Imperial year is based on the date of the legendary founding Emperor Jimmu in 660 BC.

In 1772, he fled to Osaka, changed his surname from AYABE to ASADA, where he resumed the study of astronomy, making his living by practicing medicine.

The official astronomers missed to predict the solar eclipse of Oct 07, 1763. ASADA calculated and predicted the solar eclipse for the New Year’s Day 1786 (Gregorian Calendar January 30, 1786), published as "Records Based on Observations", which suddenly made his name known to the Japanese government.

In Osaka ASADA founded the Senjikan School of Astronomy, an important school of calendrical scientists. One of his students was the wealthy merchant Shigetomi HAZAMA (1756--1816), another the later astronomer Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI since 1787. ASADA grounded optical lenses and constructed telescopes, with which he observed the moons of Jupiter or craters on the moon. In addition, he measured the Sun’s rotation by observing sunspots.

Due to the Japanese policy of isolation at the time, Western scientific knowledge only reached the island in the form of outdated Chinese works which had been translated by Jesuit missionaries in China.

Based on the first volume of the Chinese Li-hsiang k’ao-ch’eng ("Compendium of Calendrical Science", 1713) -- essentially Tychonian astronomy, which was his source for studying Western astronomy, ASADA determined the ephemerides, the positions of the Sun and the Moon, and calculated solar and lunar eclipses.

He developed methods for determining the orbits of the celestial bodies of the solar system, studying the theory of the elliptic orbit, and independently confirmed Kepler’s third law. In addition, he is credited for discovery of the socalled Sho-Cho (Hsiao-ch’ang) law, dealing with the variability in the length of the tropical year -- basis for an accurate calendar.

In 1795, the Shogunate proposed to reform the current Japanese calendar, the Horyaku Reki calendar, by using the new theories of Western astronomy. ASADA proposed -- due to his poor health -- not to appoint himself as the official astronomer, but his distinguished scholar Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI and to choose HAZAMA as an assistant. This led to the Kansei Calendar in 1797, the first based on Westen principles.

In praise of Gōryū ASADA, TAKAHASHI stated in his Zōshū shōchō hō:

"Laboring over Chinese and Western works, Asada Goryu at Osaka discovered the shocho law. Although Western astronomy is most advanced, we have not heard of its mentioning this law, known only in our country. Therefore I have said that although we are unable to boast about our achievements in comparison with those of the Westerners, my country should be proud of this man and his discovery." (World Biographical Encyclopedia)

ASADA had modernized astronomy in Japan and introduced modern astronomical instruments and methods of observation, influenced by the Western culture and science.

His numerous achievements have been recognized by naming a lunar crater "Crater Asada".

Fig. 2a. Grave of Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804), (CC3, Nekosuki600)

Fig. 2b. Monument for the cartographer Tadataka INŌ (1745--1818) in Sawara Katori City, (CC2.5, katorisi)

Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804) and Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829)

Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804), born in Osaka, was appointed official astronomer by the shogunate in 1795. Together with the astronomer ASADA and Shigetomi HAZAMA (1756--1816), he developed the Kansei Calendar, a Japanese lunisolar calendar, which was officially introduced in 1797.

TAKAHASHI translated a Dutch version of Joseph Lalande’s (1732--1807) Traité d’astronomie entitled "Lalande Calendar, Summary", 11 volumes (1803), 8 of which survived. His assistant was his son Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829), who succeeded him in 1804.

Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829), astronomer and cartographer, published in 1810 by order of the Bakufu a modern world map entitled "Reworked Map of the Whole World with All Countries". He continued by making an accurate map of Japan based on the surveys of the cartographer Tadataka INŌ (1745--1818), who became his scholar despite of being 19 years older.

Fig. 3a. Edo city map (1844/47), (CC)

Fig. 3b. Torigoe no Fuji Observatory of the Calendar Bureau, One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, artist Katsushika HOKUSAI (1834-35), (CC)

Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory in Asakusa (1782--1869)

In the late Edo era (in the time of the Tokugawa Shōgunat, 1603 to 1868), the Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory in Asakusa, East of the Torikoe Shrine (Asakusa-ku from 1878 to 1947, then changed to "Taito Ward"), in the North-East of Edo (today Tokyo) was founded in 1782/95 by Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI.

The Tenmonkata (Official Astronomer) worked and made observations under the direction of the Shogun. Timekeeping and calendar making were the main tasks of the astronomers; the astronomical office where calendars were compiled, was called Hanreki-sho Goyo Yashiki or Asakusa Tenmondai. The solar Gregorian Calendar was first introduced in 1873 as part of the Japan’s Meiji period modernization.

In addition, surveying lands, compiling geographical descriptions and translating Western books played an important role.

The Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory existed until 1869 in Taito City (former Asakusa) in Tokyo and disappeared after the Meiji Restoration (1868), when Mutsuhito Emperor MEIJI (1852--1912) became the 122. Tenno of Japan.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-13 19:18:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

In the Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science one can find an impressive collection of telescopes, instruments, globes and clocks:

Fig. 4a. Armillary sphere made of bronze, (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 4b. Quadrant (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Instruments, Telescopes, and Clocks

- Large Armillary Sphere -- the artist Katsushika HOKUSAI (1760--1849) created a famous woodblock print series One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, Torikoe no Fuji. One painting shows the astronomical observatory against a backdrop of Mt. Fuji, which was seen from Torikoe Shrine.

- Quadrant, medium-size quadrant with a radius of approximately 115cm, created by Shigetomi HAZAMA, a teacher of Tadataka INO, referring to "Reidai Gishoshi" (written by Ferdinand Verbiest in 1674), used for surveying.

- Quadrant, large quadrant with a radius of approximately 182cm

- Map making tools of the surveyor and cartographer Tadataka INO (1745--1818)

- Japanese Terrestrial Globe (18th century)

The map on the globe is based on the world map created by the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci. In Japan, the first terrestrial and celestial globes were created by Shunkai Shibukawa, an official astronomer of the shogunate, in 1690.

- Celestial Globe (1855)

This celestial globe is based on "Gisho Kosei" published in 1752, which adopted Western astronomy. But normally Japanese astronomy in the Edo era was influenced by Chinese astronomy, which used constellations typical in China. It is interesting that daily positions of Comet Donati (1858) are marked.

- Telescopes of the Edo Period

- Japanese clocks: small pillow clocks, bracket clocks, portable clocks used in front of lanterns, hanging bell shaped clocks

- Pillar Clocks

- Drum Clocks

- Double balance large pedestal clock: This large clock has a mechanism made of iron, a sun hand, a lunar phase display, an alarm function with four legs.

- 20-cm-Equatorial Refracting Telescope, made by Troughton & Simms, imported by the Meiji Government in 1880.

Fig. 5a. Reflecting telescope (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 5b. Wadokei Japonese Clock à-double-foliot, Edo era, Le Musée Paul Dupuy (CC4, Didier Descouens)

Historical books:

Heitengi Zukai (1802)

"Heitengi Zukai", a handbook of astronomy, was written by Zenbe Iwasaki, who was also a maker of telescopes.

The Astronomical Herald, vol. 3 (1910)

"The Astronomical Herald" is a journal of the Astronomical Society of Japan, founded in 1908. The book contains observations of Halley’s Comet (1910).

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:29:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6. Ruins of the Astronomical Observatory (1782-1869) in Asakusa (credit: Taito City)

The Astronomical Observatory in Edo-Asakusa (1782) existed only until 1869, now there are ruins (Tokio-Taito City).

But a good collection of astronomical instruments is preserved in the Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:30:41

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Hockey, Thomas: Asada Goryu (1734--1799). In: The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer Publishing 2007.

- Keene, D.: The Japanese Discovery of Europe, 1720--1830. Stanford University Press 1969, p. 152.

- Lane, Richard: Hokusai: Life and Work. E.P. Dutton 1989.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: A History of Japanese Astronomy: Chinese Background and Western Impact. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press 1969.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: "Asada Goryu". In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons 1970, p. 310-314.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: Japanese Scientific Thought. In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 15 (Suppl. 1). Edited by Charles Coulston Gillispie. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, p. 728-758.

- Sugimoto, Masayoshi & David L. Swain: Science and Culture in Traditional Japan. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle and Co. 1989.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Ino Tadataka. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 608.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Takahashi Kageyasu. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 1506.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Takahashi Yoshitoki. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 1507.

- Otani, Ryokichi: Tadataka Ino: The Japanese Land-Surveyor. Simon Publications 2001, p. 33 ff.

- Shinkai, Hisaaki: Goryu Asada and Kepler’s third law of planetary motion. In: Kyoto University (Hg.): Memoirs of Osaka Institute of Technology, Band 61, Nr. 2. Osaka 2016, p. 27-36.

- Renshaw, Steven L. & Saori Ihara: Asada, Goryu. In: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer 2007, p. 64-65.

- Renshaw, Steven L.: Asada, Goryu. In: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer 2014, p. 110-111.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:32:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Asada Goryu (Wikipedia)

- World Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Springer)

- Barley shochu GORYU [Oita’s second man] About Goryu Asada

- Takahashi Yoshitoki (Wikipedia)

- Takahashi Kageyasu (Wikipedia)

- Ino Tadataka (1745--1818) (Wikipedia)

- Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science, Admiring Scientists’ Unquenchable Spirit of Inquiry in the Edo Period

Links to external on-line pictures - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-10 18:23:51

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no information available

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-10 18:23:49

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

-

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 10

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-13 19:23:36

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

![Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799), (www.g](/images/astronomicalheritage.net/gallery/ahp_entities/entity000248/ASADA-Goryu-1734-1799.png)

Fig. 1a. Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799), (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 1b. Gōryū ASADA’s calculations -- Japan’s oldest lunar observation map (Stadtbibliothek Kitsuki)

Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799)

Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799) was a Japanese astronomer and anatomist / Confucian physician. In addition to his work as a physician of his fief, his liege lord, since 1767, ASADA initially dealt with creating calendars. The Japanese Imperial year is based on the date of the legendary founding Emperor Jimmu in 660 BC.

In 1772, he fled to Osaka, changed his surname from AYABE to ASADA, where he resumed the study of astronomy, making his living by practicing medicine.

The official astronomers missed to predict the solar eclipse of Oct 07, 1763. ASADA calculated and predicted the solar eclipse for the New Year’s Day 1786 (Gregorian Calendar January 30, 1786), published as "Records Based on Observations", which suddenly made his name known to the Japanese government.

In Osaka ASADA founded the Senjikan School of Astronomy, an important school of calendrical scientists. One of his students was the wealthy merchant Shigetomi HAZAMA (1756--1816), another the later astronomer Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI since 1787. ASADA grounded optical lenses and constructed telescopes, with which he observed the moons of Jupiter or craters on the moon. In addition, he measured the Sun’s rotation by observing sunspots.

Due to the Japanese policy of isolation at the time, Western scientific knowledge only reached the island in the form of outdated Chinese works which had been translated by Jesuit missionaries in China.

Based on the first volume of the Chinese Li-hsiang k’ao-ch’eng ("Compendium of Calendrical Science", 1713) -- essentially Tychonian astronomy, which was his source for studying Western astronomy, ASADA determined the ephemerides, the positions of the Sun and the Moon, and calculated solar and lunar eclipses.

He developed methods for determining the orbits of the celestial bodies of the solar system, studying the theory of the elliptic orbit, and independently confirmed Kepler’s third law. In addition, he is credited for discovery of the socalled Sho-Cho (Hsiao-ch’ang) law, dealing with the variability in the length of the tropical year -- basis for an accurate calendar.

In 1795, the Shogunate proposed to reform the current Japanese calendar, the Horyaku Reki calendar, by using the new theories of Western astronomy. ASADA proposed -- due to his poor health -- not to appoint himself as the official astronomer, but his distinguished scholar Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI and to choose HAZAMA as an assistant. This led to the Kansei Calendar in 1797, the first based on Westen principles.

In praise of Gōryū ASADA, TAKAHASHI stated in his Zōshū shōchō hō:

"Laboring over Chinese and Western works, Asada Goryu at Osaka discovered the shocho law. Although Western astronomy is most advanced, we have not heard of its mentioning this law, known only in our country. Therefore I have said that although we are unable to boast about our achievements in comparison with those of the Westerners, my country should be proud of this man and his discovery." (World Biographical Encyclopedia)

ASADA had modernized astronomy in Japan and introduced modern astronomical instruments and methods of observation, influenced by the Western culture and science.

His numerous achievements have been recognized by naming a lunar crater "Crater Asada".

Fig. 2a. Grave of Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804), (CC3, Nekosuki600)

Fig. 2b. Monument for the cartographer Tadataka INŌ (1745--1818) in Sawara Katori City, (CC2.5, katorisi)

Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804) and Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829)

Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804), born in Osaka, was appointed official astronomer by the shogunate in 1795. Together with the astronomer ASADA and Shigetomi HAZAMA (1756--1816), he developed the Kansei Calendar, a Japanese lunisolar calendar, which was officially introduced in 1797.

TAKAHASHI translated a Dutch version of Joseph Lalande’s (1732--1807) Traité d’astronomie entitled "Lalande Calendar, Summary", 11 volumes (1803), 8 of which survived. His assistant was his son Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829), who succeeded him in 1804.

Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829), astronomer and cartographer, published in 1810 by order of the Bakufu a modern world map entitled "Reworked Map of the Whole World with All Countries". He continued by making an accurate map of Japan based on the surveys of the cartographer Tadataka INŌ (1745--1818), who became his scholar despite of being 19 years older.

Fig. 3a. Edo city map (1844/47), (CC)

Fig. 3b. Torigoe no Fuji Observatory of the Calendar Bureau, One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, artist Katsushika HOKUSAI (1834-35), (CC)

Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory in Asakusa (1782--1869)

In the late Edo era (in the time of the Tokugawa Shōgunat, 1603 to 1868), the Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory in Asakusa, East of the Torikoe Shrine (Asakusa-ku from 1878 to 1947, then changed to "Taito Ward"), in the North-East of Edo (today Tokyo) was founded in 1782/95 by Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI.

The Tenmonkata (Official Astronomer) worked and made observations under the direction of the Shogun. Timekeeping and calendar making were the main tasks of the astronomers; the astronomical office where calendars were compiled, was called Hanreki-sho Goyo Yashiki or Asakusa Tenmondai. The solar Gregorian Calendar was first introduced in 1873 as part of the Japan’s Meiji period modernization.

In addition, surveying lands, compiling geographical descriptions and translating Western books played an important role.

The Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory existed until 1869 in Taito City (former Asakusa) in Tokyo and disappeared after the Meiji Restoration (1868), when Mutsuhito Emperor MEIJI (1852--1912) became the 122. Tenno of Japan.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-13 19:18:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

In the Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science one can find an impressive collection of telescopes, instruments, globes and clocks:

Fig. 4a. Armillary sphere made of bronze, (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 4b. Quadrant (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Instruments, Telescopes, and Clocks

- Large Armillary Sphere -- the artist Katsushika HOKUSAI (1760--1849) created a famous woodblock print series One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, Torikoe no Fuji. One painting shows the astronomical observatory against a backdrop of Mt. Fuji, which was seen from Torikoe Shrine.

- Quadrant, medium-size quadrant with a radius of approximately 115cm, created by Shigetomi HAZAMA, a teacher of Tadataka INO, referring to "Reidai Gishoshi" (written by Ferdinand Verbiest in 1674), used for surveying.

- Quadrant, large quadrant with a radius of approximately 182cm

- Map making tools of the surveyor and cartographer Tadataka INO (1745--1818)

- Japanese Terrestrial Globe (18th century)

The map on the globe is based on the world map created by the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci. In Japan, the first terrestrial and celestial globes were created by Shunkai Shibukawa, an official astronomer of the shogunate, in 1690.

- Celestial Globe (1855)

This celestial globe is based on "Gisho Kosei" published in 1752, which adopted Western astronomy. But normally Japanese astronomy in the Edo era was influenced by Chinese astronomy, which used constellations typical in China. It is interesting that daily positions of Comet Donati (1858) are marked.

- Telescopes of the Edo Period

- Japanese clocks: small pillow clocks, bracket clocks, portable clocks used in front of lanterns, hanging bell shaped clocks

- Pillar Clocks

- Drum Clocks

- Double balance large pedestal clock: This large clock has a mechanism made of iron, a sun hand, a lunar phase display, an alarm function with four legs.

- 20-cm-Equatorial Refracting Telescope, made by Troughton & Simms, imported by the Meiji Government in 1880.

Fig. 5a. Reflecting telescope (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 5b. Wadokei Japonese Clock à-double-foliot, Edo era, Le Musée Paul Dupuy (CC4, Didier Descouens)

Historical books:

Heitengi Zukai (1802)

"Heitengi Zukai", a handbook of astronomy, was written by Zenbe Iwasaki, who was also a maker of telescopes.

The Astronomical Herald, vol. 3 (1910)

"The Astronomical Herald" is a journal of the Astronomical Society of Japan, founded in 1908. The book contains observations of Halley’s Comet (1910).

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:29:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6. Ruins of the Astronomical Observatory (1782-1869) in Asakusa (credit: Taito City)

The Astronomical Observatory in Edo-Asakusa (1782) existed only until 1869, now there are ruins (Tokio-Taito City).

But a good collection of astronomical instruments is preserved in the Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:30:41

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Hockey, Thomas: Asada Goryu (1734--1799). In: The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer Publishing 2007.

- Keene, D.: The Japanese Discovery of Europe, 1720--1830. Stanford University Press 1969, p. 152.

- Lane, Richard: Hokusai: Life and Work. E.P. Dutton 1989.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: A History of Japanese Astronomy: Chinese Background and Western Impact. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press 1969.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: "Asada Goryu". In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons 1970, p. 310-314.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: Japanese Scientific Thought. In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 15 (Suppl. 1). Edited by Charles Coulston Gillispie. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, p. 728-758.

- Sugimoto, Masayoshi & David L. Swain: Science and Culture in Traditional Japan. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle and Co. 1989.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Ino Tadataka. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 608.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Takahashi Kageyasu. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 1506.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Takahashi Yoshitoki. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 1507.

- Otani, Ryokichi: Tadataka Ino: The Japanese Land-Surveyor. Simon Publications 2001, p. 33 ff.

- Shinkai, Hisaaki: Goryu Asada and Kepler’s third law of planetary motion. In: Kyoto University (Hg.): Memoirs of Osaka Institute of Technology, Band 61, Nr. 2. Osaka 2016, p. 27-36.

- Renshaw, Steven L. & Saori Ihara: Asada, Goryu. In: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer 2007, p. 64-65.

- Renshaw, Steven L.: Asada, Goryu. In: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer 2014, p. 110-111.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:32:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Asada Goryu (Wikipedia)

- World Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Springer)

- Barley shochu GORYU [Oita’s second man] About Goryu Asada

- Takahashi Yoshitoki (Wikipedia)

- Takahashi Kageyasu (Wikipedia)

- Ino Tadataka (1745--1818) (Wikipedia)

- Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science, Admiring Scientists’ Unquenchable Spirit of Inquiry in the Edo Period

Links to external on-line pictures - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-10 18:23:51

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no information available

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 10

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-13 19:23:36

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

![Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799), (www.g](/images/astronomicalheritage.net/gallery/ahp_entities/entity000248/ASADA-Goryu-1734-1799.png)

Fig. 1a. Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799), (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 1b. Gōryū ASADA’s calculations -- Japan’s oldest lunar observation map (Stadtbibliothek Kitsuki)

Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799)

Gōryū ASADA [Yasuaki AYABE] (1734--1799) was a Japanese astronomer and anatomist / Confucian physician. In addition to his work as a physician of his fief, his liege lord, since 1767, ASADA initially dealt with creating calendars. The Japanese Imperial year is based on the date of the legendary founding Emperor Jimmu in 660 BC.

In 1772, he fled to Osaka, changed his surname from AYABE to ASADA, where he resumed the study of astronomy, making his living by practicing medicine.

The official astronomers missed to predict the solar eclipse of Oct 07, 1763. ASADA calculated and predicted the solar eclipse for the New Year’s Day 1786 (Gregorian Calendar January 30, 1786), published as "Records Based on Observations", which suddenly made his name known to the Japanese government.

In Osaka ASADA founded the Senjikan School of Astronomy, an important school of calendrical scientists. One of his students was the wealthy merchant Shigetomi HAZAMA (1756--1816), another the later astronomer Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI since 1787. ASADA grounded optical lenses and constructed telescopes, with which he observed the moons of Jupiter or craters on the moon. In addition, he measured the Sun’s rotation by observing sunspots.

Due to the Japanese policy of isolation at the time, Western scientific knowledge only reached the island in the form of outdated Chinese works which had been translated by Jesuit missionaries in China.

Based on the first volume of the Chinese Li-hsiang k’ao-ch’eng ("Compendium of Calendrical Science", 1713) -- essentially Tychonian astronomy, which was his source for studying Western astronomy, ASADA determined the ephemerides, the positions of the Sun and the Moon, and calculated solar and lunar eclipses.

He developed methods for determining the orbits of the celestial bodies of the solar system, studying the theory of the elliptic orbit, and independently confirmed Kepler’s third law. In addition, he is credited for discovery of the socalled Sho-Cho (Hsiao-ch’ang) law, dealing with the variability in the length of the tropical year -- basis for an accurate calendar.

In 1795, the Shogunate proposed to reform the current Japanese calendar, the Horyaku Reki calendar, by using the new theories of Western astronomy. ASADA proposed -- due to his poor health -- not to appoint himself as the official astronomer, but his distinguished scholar Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI and to choose HAZAMA as an assistant. This led to the Kansei Calendar in 1797, the first based on Westen principles.

In praise of Gōryū ASADA, TAKAHASHI stated in his Zōshū shōchō hō:

"Laboring over Chinese and Western works, Asada Goryu at Osaka discovered the shocho law. Although Western astronomy is most advanced, we have not heard of its mentioning this law, known only in our country. Therefore I have said that although we are unable to boast about our achievements in comparison with those of the Westerners, my country should be proud of this man and his discovery." (World Biographical Encyclopedia)

ASADA had modernized astronomy in Japan and introduced modern astronomical instruments and methods of observation, influenced by the Western culture and science.

His numerous achievements have been recognized by naming a lunar crater "Crater Asada".

Fig. 2a. Grave of Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804), (CC3, Nekosuki600)

Fig. 2b. Monument for the cartographer Tadataka INŌ (1745--1818) in Sawara Katori City, (CC2.5, katorisi)

Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804) and Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829)

Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI (1764--1804), born in Osaka, was appointed official astronomer by the shogunate in 1795. Together with the astronomer ASADA and Shigetomi HAZAMA (1756--1816), he developed the Kansei Calendar, a Japanese lunisolar calendar, which was officially introduced in 1797.

TAKAHASHI translated a Dutch version of Joseph Lalande’s (1732--1807) Traité d’astronomie entitled "Lalande Calendar, Summary", 11 volumes (1803), 8 of which survived. His assistant was his son Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829), who succeeded him in 1804.

Kageyasu TAKAHASHI (1785--1829), astronomer and cartographer, published in 1810 by order of the Bakufu a modern world map entitled "Reworked Map of the Whole World with All Countries". He continued by making an accurate map of Japan based on the surveys of the cartographer Tadataka INŌ (1745--1818), who became his scholar despite of being 19 years older.

Fig. 3a. Edo city map (1844/47), (CC)

Fig. 3b. Torigoe no Fuji Observatory of the Calendar Bureau, One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, artist Katsushika HOKUSAI (1834-35), (CC)

Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory in Asakusa (1782--1869)

In the late Edo era (in the time of the Tokugawa Shōgunat, 1603 to 1868), the Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory in Asakusa, East of the Torikoe Shrine (Asakusa-ku from 1878 to 1947, then changed to "Taito Ward"), in the North-East of Edo (today Tokyo) was founded in 1782/95 by Yoshitoki TAKAHASHI.

The Tenmonkata (Official Astronomer) worked and made observations under the direction of the Shogun. Timekeeping and calendar making were the main tasks of the astronomers; the astronomical office where calendars were compiled, was called Hanreki-sho Goyo Yashiki or Asakusa Tenmondai. The solar Gregorian Calendar was first introduced in 1873 as part of the Japan’s Meiji period modernization.

In addition, surveying lands, compiling geographical descriptions and translating Western books played an important role.

The Shōgunate Astronomical Observatory existed until 1869 in Taito City (former Asakusa) in Tokyo and disappeared after the Meiji Restoration (1868), when Mutsuhito Emperor MEIJI (1852--1912) became the 122. Tenno of Japan.

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-13 19:18:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

In the Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science one can find an impressive collection of telescopes, instruments, globes and clocks:

Fig. 4a. Armillary sphere made of bronze, (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 4b. Quadrant (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Instruments, Telescopes, and Clocks

- Large Armillary Sphere -- the artist Katsushika HOKUSAI (1760--1849) created a famous woodblock print series One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, Torikoe no Fuji. One painting shows the astronomical observatory against a backdrop of Mt. Fuji, which was seen from Torikoe Shrine.

- Quadrant, medium-size quadrant with a radius of approximately 115cm, created by Shigetomi HAZAMA, a teacher of Tadataka INO, referring to "Reidai Gishoshi" (written by Ferdinand Verbiest in 1674), used for surveying.

- Quadrant, large quadrant with a radius of approximately 182cm

- Map making tools of the surveyor and cartographer Tadataka INO (1745--1818)

- Japanese Terrestrial Globe (18th century)

The map on the globe is based on the world map created by the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci. In Japan, the first terrestrial and celestial globes were created by Shunkai Shibukawa, an official astronomer of the shogunate, in 1690.

- Celestial Globe (1855)

This celestial globe is based on "Gisho Kosei" published in 1752, which adopted Western astronomy. But normally Japanese astronomy in the Edo era was influenced by Chinese astronomy, which used constellations typical in China. It is interesting that daily positions of Comet Donati (1858) are marked.

- Telescopes of the Edo Period

- Japanese clocks: small pillow clocks, bracket clocks, portable clocks used in front of lanterns, hanging bell shaped clocks

- Pillar Clocks

- Drum Clocks

- Double balance large pedestal clock: This large clock has a mechanism made of iron, a sun hand, a lunar phase display, an alarm function with four legs.

- 20-cm-Equatorial Refracting Telescope, made by Troughton & Simms, imported by the Meiji Government in 1880.

Fig. 5a. Reflecting telescope (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 5b. Wadokei Japonese Clock à-double-foliot, Edo era, Le Musée Paul Dupuy (CC4, Didier Descouens)

Historical books:

Heitengi Zukai (1802)

"Heitengi Zukai", a handbook of astronomy, was written by Zenbe Iwasaki, who was also a maker of telescopes.

The Astronomical Herald, vol. 3 (1910)

"The Astronomical Herald" is a journal of the Astronomical Society of Japan, founded in 1908. The book contains observations of Halley’s Comet (1910).

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:29:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6. Ruins of the Astronomical Observatory (1782-1869) in Asakusa (credit: Taito City)

The Astronomical Observatory in Edo-Asakusa (1782) existed only until 1869, now there are ruins (Tokio-Taito City).

But a good collection of astronomical instruments is preserved in the Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:30:41

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Hockey, Thomas: Asada Goryu (1734--1799). In: The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer Publishing 2007.

- Keene, D.: The Japanese Discovery of Europe, 1720--1830. Stanford University Press 1969, p. 152.

- Lane, Richard: Hokusai: Life and Work. E.P. Dutton 1989.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: A History of Japanese Astronomy: Chinese Background and Western Impact. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press 1969.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: "Asada Goryu". In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons 1970, p. 310-314.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: Japanese Scientific Thought. In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 15 (Suppl. 1). Edited by Charles Coulston Gillispie. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, p. 728-758.

- Sugimoto, Masayoshi & David L. Swain: Science and Culture in Traditional Japan. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle and Co. 1989.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Ino Tadataka. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 608.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Takahashi Kageyasu. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 1506.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Takahashi Yoshitoki. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 1507.

- Otani, Ryokichi: Tadataka Ino: The Japanese Land-Surveyor. Simon Publications 2001, p. 33 ff.

- Shinkai, Hisaaki: Goryu Asada and Kepler’s third law of planetary motion. In: Kyoto University (Hg.): Memoirs of Osaka Institute of Technology, Band 61, Nr. 2. Osaka 2016, p. 27-36.

- Renshaw, Steven L. & Saori Ihara: Asada, Goryu. In: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer 2007, p. 64-65.

- Renshaw, Steven L.: Asada, Goryu. In: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer 2014, p. 110-111.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:32:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Asada Goryu (Wikipedia)

- World Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Springer)

- Barley shochu GORYU [Oita’s second man] About Goryu Asada

- Takahashi Yoshitoki (Wikipedia)

- Takahashi Kageyasu (Wikipedia)

- Ino Tadataka (1745--1818) (Wikipedia)

- Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science, Admiring Scientists’ Unquenchable Spirit of Inquiry in the Edo Period

Links to external on-line pictures - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-10 18:23:51

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no information available

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-13 19:18:46

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

In the Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science one can find an impressive collection of telescopes, instruments, globes and clocks:

Fig. 4a. Armillary sphere made of bronze, (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 4b. Quadrant (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Instruments, Telescopes, and Clocks

- Large Armillary Sphere -- the artist Katsushika HOKUSAI (1760--1849) created a famous woodblock print series One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, Torikoe no Fuji. One painting shows the astronomical observatory against a backdrop of Mt. Fuji, which was seen from Torikoe Shrine.

- Quadrant, medium-size quadrant with a radius of approximately 115cm, created by Shigetomi HAZAMA, a teacher of Tadataka INO, referring to "Reidai Gishoshi" (written by Ferdinand Verbiest in 1674), used for surveying.

- Quadrant, large quadrant with a radius of approximately 182cm

- Map making tools of the surveyor and cartographer Tadataka INO (1745--1818)

- Japanese Terrestrial Globe (18th century)

The map on the globe is based on the world map created by the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci. In Japan, the first terrestrial and celestial globes were created by Shunkai Shibukawa, an official astronomer of the shogunate, in 1690. - Celestial Globe (1855)

This celestial globe is based on "Gisho Kosei" published in 1752, which adopted Western astronomy. But normally Japanese astronomy in the Edo era was influenced by Chinese astronomy, which used constellations typical in China. It is interesting that daily positions of Comet Donati (1858) are marked. - Telescopes of the Edo Period

- Japanese clocks: small pillow clocks, bracket clocks, portable clocks used in front of lanterns, hanging bell shaped clocks

- Pillar Clocks

- Drum Clocks

- Double balance large pedestal clock: This large clock has a mechanism made of iron, a sun hand, a lunar phase display, an alarm function with four legs.

- 20-cm-Equatorial Refracting Telescope, made by Troughton & Simms, imported by the Meiji Government in 1880.

Fig. 5a. Reflecting telescope (www.goryu.jp/aboutasada.htm)

Fig. 5b. Wadokei Japonese Clock à-double-foliot, Edo era, Le Musée Paul Dupuy (CC4, Didier Descouens)

Historical books:

Heitengi Zukai (1802)

"Heitengi Zukai", a handbook of astronomy, was written by Zenbe Iwasaki, who was also a maker of telescopes.

The Astronomical Herald, vol. 3 (1910)

"The Astronomical Herald" is a journal of the Astronomical Society of Japan, founded in 1908. The book contains observations of Halley’s Comet (1910).

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:29:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6. Ruins of the Astronomical Observatory (1782-1869) in Asakusa (credit: Taito City)

The Astronomical Observatory in Edo-Asakusa (1782) existed only until 1869, now there are ruins (Tokio-Taito City).

But a good collection of astronomical instruments is preserved in the Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:30:41

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Hockey, Thomas: Asada Goryu (1734--1799). In: The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer Publishing 2007.

- Keene, D.: The Japanese Discovery of Europe, 1720--1830. Stanford University Press 1969, p. 152.

- Lane, Richard: Hokusai: Life and Work. E.P. Dutton 1989.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: A History of Japanese Astronomy: Chinese Background and Western Impact. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press 1969.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: "Asada Goryu". In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons 1970, p. 310-314.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: Japanese Scientific Thought. In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 15 (Suppl. 1). Edited by Charles Coulston Gillispie. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, p. 728-758.

- Sugimoto, Masayoshi & David L. Swain: Science and Culture in Traditional Japan. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle and Co. 1989.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Ino Tadataka. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 608.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Takahashi Kageyasu. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 1506.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Takahashi Yoshitoki. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 1507.

- Otani, Ryokichi: Tadataka Ino: The Japanese Land-Surveyor. Simon Publications 2001, p. 33 ff.

- Shinkai, Hisaaki: Goryu Asada and Kepler’s third law of planetary motion. In: Kyoto University (Hg.): Memoirs of Osaka Institute of Technology, Band 61, Nr. 2. Osaka 2016, p. 27-36.

- Renshaw, Steven L. & Saori Ihara: Asada, Goryu. In: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer 2007, p. 64-65.

- Renshaw, Steven L.: Asada, Goryu. In: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer 2014, p. 110-111.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:32:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Asada Goryu (Wikipedia)

- World Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Springer)

- Barley shochu GORYU [Oita’s second man] About Goryu Asada

- Takahashi Yoshitoki (Wikipedia)

- Takahashi Kageyasu (Wikipedia)

- Ino Tadataka (1745--1818) (Wikipedia)

- Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science, Admiring Scientists’ Unquenchable Spirit of Inquiry in the Edo Period

Links to external on-line pictures - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-10 18:23:51

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no information available

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:29:32

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 6. Ruins of the Astronomical Observatory (1782-1869) in Asakusa (credit: Taito City)

The Astronomical Observatory in Edo-Asakusa (1782) existed only until 1869, now there are ruins (Tokio-Taito City).

But a good collection of astronomical instruments is preserved in the Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:30:41

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Hockey, Thomas: Asada Goryu (1734--1799). In: The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer Publishing 2007.

- Keene, D.: The Japanese Discovery of Europe, 1720--1830. Stanford University Press 1969, p. 152.

- Lane, Richard: Hokusai: Life and Work. E.P. Dutton 1989.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: A History of Japanese Astronomy: Chinese Background and Western Impact. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press 1969.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: "Asada Goryu". In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons 1970, p. 310-314.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: Japanese Scientific Thought. In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 15 (Suppl. 1). Edited by Charles Coulston Gillispie. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, p. 728-758.

- Sugimoto, Masayoshi & David L. Swain: Science and Culture in Traditional Japan. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle and Co. 1989.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Ino Tadataka. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 608.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Takahashi Kageyasu. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 1506.

- Noma, S. (ed.): Takahashi Yoshitoki. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha 1993, p. 1507.

- Otani, Ryokichi: Tadataka Ino: The Japanese Land-Surveyor. Simon Publications 2001, p. 33 ff.

- Shinkai, Hisaaki: Goryu Asada and Kepler’s third law of planetary motion. In: Kyoto University (Hg.): Memoirs of Osaka Institute of Technology, Band 61, Nr. 2. Osaka 2016, p. 27-36.

- Renshaw, Steven L. & Saori Ihara: Asada, Goryu. In: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer 2007, p. 64-65.

- Renshaw, Steven L.: Asada, Goryu. In: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer 2014, p. 110-111.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:32:53

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Asada Goryu (Wikipedia)

- World Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Springer)

- Barley shochu GORYU [Oita’s second man] About Goryu Asada

- Takahashi Yoshitoki (Wikipedia)

- Takahashi Kageyasu (Wikipedia)

- Ino Tadataka (1745--1818) (Wikipedia)

- Taito City National Museum of Nature and Science, Admiring Scientists’ Unquenchable Spirit of Inquiry in the Edo Period

Links to external on-line pictures - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-10 18:23:51

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no information available

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 248

Subentity: 1

Version: 5

Status: PUB

Date: 2023-03-12 02:30:41

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Hockey, Thomas: Asada Goryu (1734--1799). In: The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer Publishing 2007.

- Keene, D.: The Japanese Discovery of Europe, 1720--1830. Stanford University Press 1969, p. 152.

- Lane, Richard: Hokusai: Life and Work. E.P. Dutton 1989.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: A History of Japanese Astronomy: Chinese Background and Western Impact. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press 1969.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: "Asada Goryu". In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons 1970, p. 310-314.

- Nakayama, Shigeru: Japanese Scientific Thought. In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 15 (Suppl. 1). Edited by Charles Coulston Gillispie. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, p. 728-758.