Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Strasbourg Cathedral, France, and astronomical time

Format: Short Description (ICOMOS-IAU Case Study format)

Presentation

Geographical position - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

City of Strasbourg, Département du Bas-Rhin, Alsace region, France.

Location - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:17:03

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

Latitude 48° 34′ 55″ N, longitude 7° 45′ 5″ E. Elevation 150m above mean sea level.

General description - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:21:24

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral of Notre Dame, constructed from the 11th to the 14th centuries, forms the core of this site. Several original timekeepers which have been removed from the cathedral are now in Strasbourg’s Museum of Decorative Arts and Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame. The Cathedral forms part of the World Heritage property Strasbourg-Grande Île inscribed on the List in 1988 under criteria (i), (ii) and (iv).

Brief inventory - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:28:02

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

Inventory of the remains related to astronomy:

Location Description Sundials

Niche in buttress of south transept; original in Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame Statue of youth with a sundial (1225 × 1235) Gable of south transept Three vertical sundials, Conrad Dasypodius (1572) Exterior wall of the Treasury Vertical sundial (1488?) Exterior buttress of the Treasury Vertical sundial (15th century) South transept above clock; original in Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame Relief of astrologer with a sundial (c. 1490) Inside door of south transept Meridian line (1838-42) Tower’s four sides at platform level Four vertical dials (16th century) Tower’s south side at platform level Meridian with triangular stylus and single vertical noon line (16th century) Tower Statue of man holding sundial-like shield with concentric circles (late 15th century) Clocks

South transept, above entrance External clock shows hour of day and day of week (and corresponding planet) Formerly opposite the present clock in the South Transept; cock-automaton in Museum of Decorative Arts First astronomical clock (1352-4) Formerly in the location of the present clock in the south transept; mechanism now in Museum of Decorative Arts Second astronomical clock (1571-4), Conrad Dasypodius In the south transept Third astronomical clock (1838-42), Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué Zodiac

West front, right portal, niches in bases of statues Zodiac and occupations of the months (late 13th-early 14th centuries)

History - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 10

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-08-16 22:09:10

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

With the construction of the west front, the cathedral obtained its earliest known display of astronomical time—one that the cathedral shares with many other large churches—the carved reliefs depicting the signs of the zodiac and the labours of the months in the bases of the statues flanking the right portal (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Occupations of the months and signs of the zodiac, west façade, right portal—May, Gemini; June, Cancer; July, Leo; August, Virgo.

Photograph © Ad Meskens, Creative Commons Licence The most widely known of these astronomical displays of are the cathedral’s elaborate astronomical clocks. The 14th-century clock included a calendar, a mechanically driven stereographic projection showing the movement of the stars, and pointers showing the positions of the Sun and Moon. Atop the clock was an automaton of a cockerel, which crowed at noon, flapping its wings.

The 16th-century clock added to these elements a rotating celestial sphere on which were depicted all 1020 stars of Ptolemy’s star catalogue together with figures of 48 constellations, a disc showing the ecclesiastical calendar for 100 years, and depictions of all eclipses over an interval of 32 years. A stereographic projection of the stars, Sun and Moon, like the one in the original clock, was enhanced with additional pointers showing the positions of all the visible planets and the Dragon, or lunar node, which served to explain eclipses (Fig. 2). Elements of the case and display were incorporated into the current clock. Although the clock reflected the geocentric model of astronomy, its decoration included a portrait of Nicolas Copernicus.

Fig. 2: Astrolabe planetary dial of the second astronomical clock. Detail from Woodcut by Tobias Stimmer (1574) The 19th-century clock reflected Copernican astronomical concepts. The geocentric stereographic projection of the Sun, Moon, and planets was replaced by a heliocentric model of the visible planets, plus the Earth and Moon, in the solar system (Fig. 2b). It displayed both uniform civil time and the apparent time indicated by the daily motions of the Sun. The stellar globe now portrayed more than 5000 stars, extending down to faint sixth magnitude ones. In addition, the clock incorporated a perpetual calendar, computing the solar cycle of 28 years, the lunar cycle of 19 years, the date of Easter, and other calendrical parameters traditionally found in ecclesiastical computus.

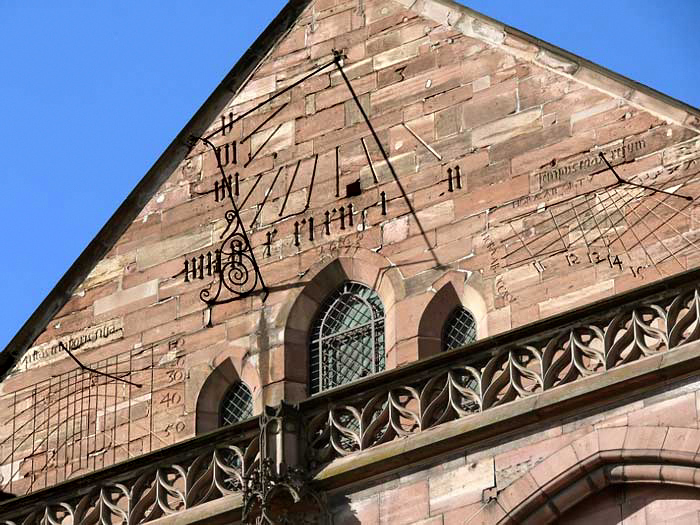

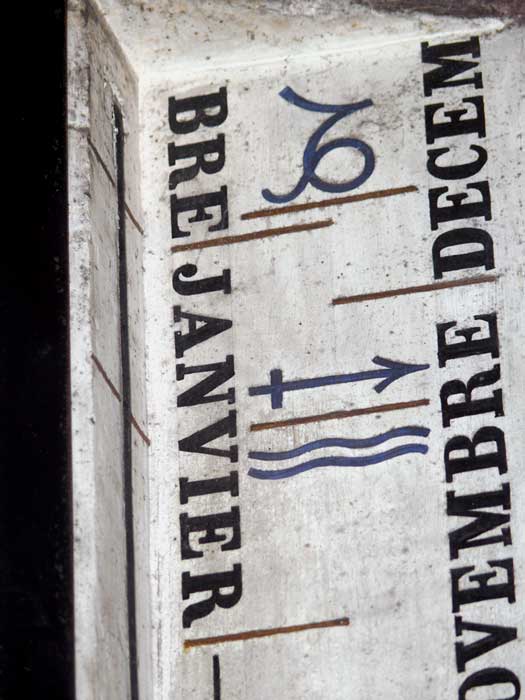

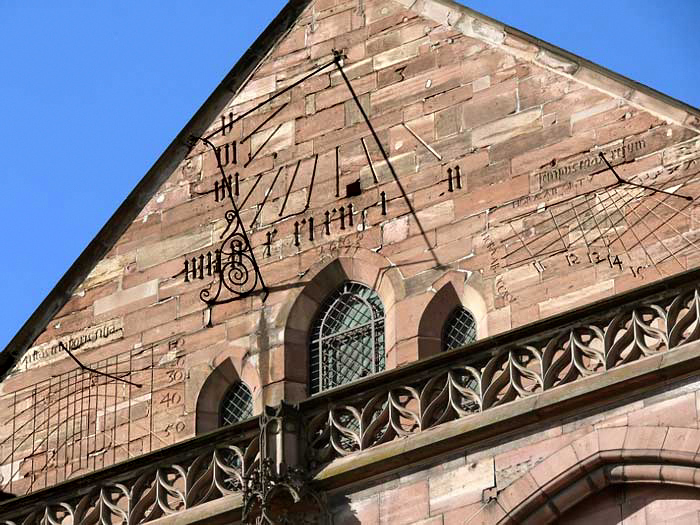

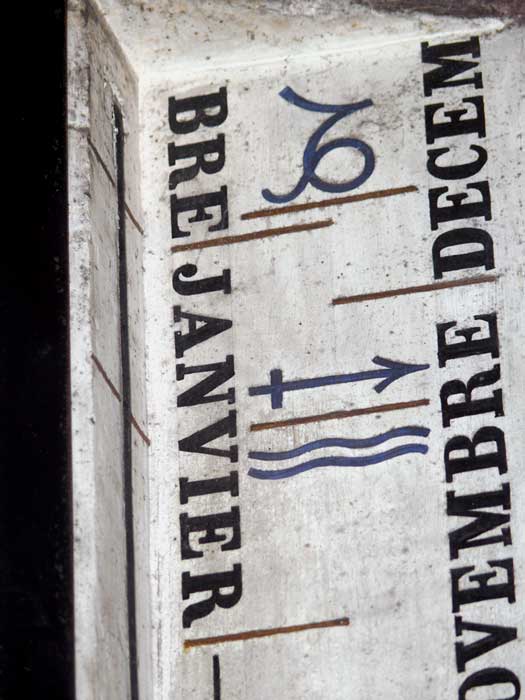

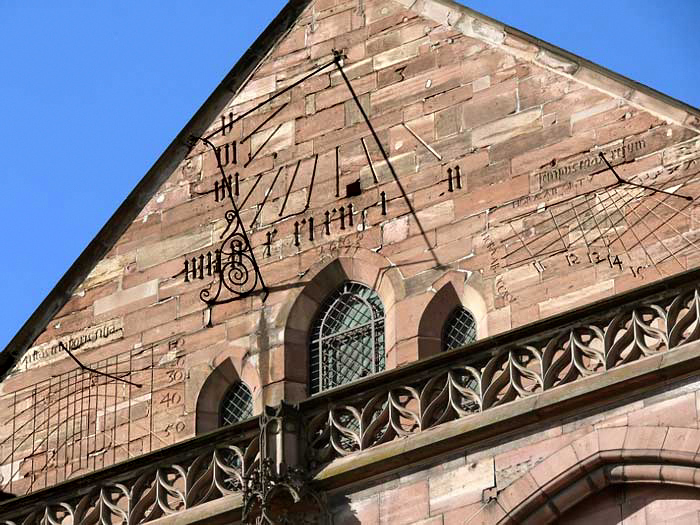

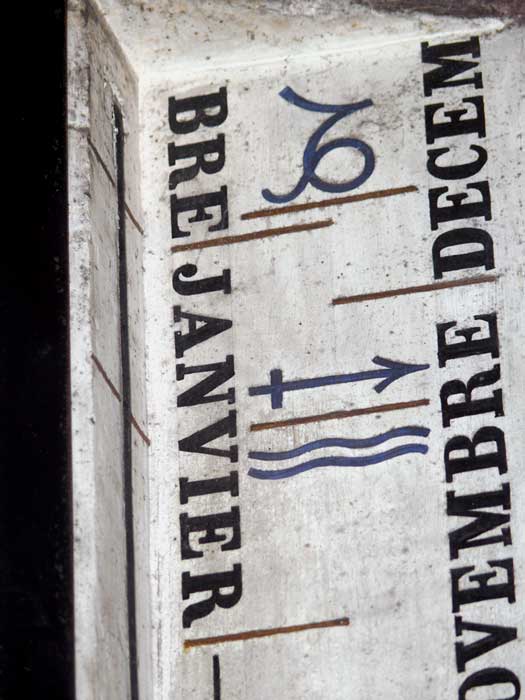

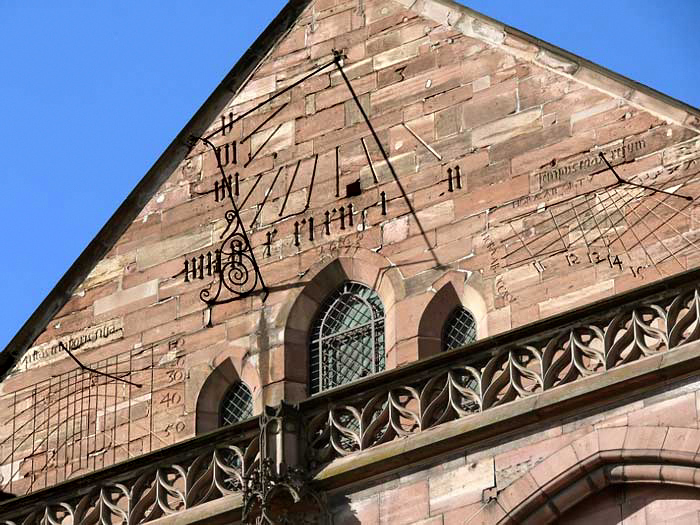

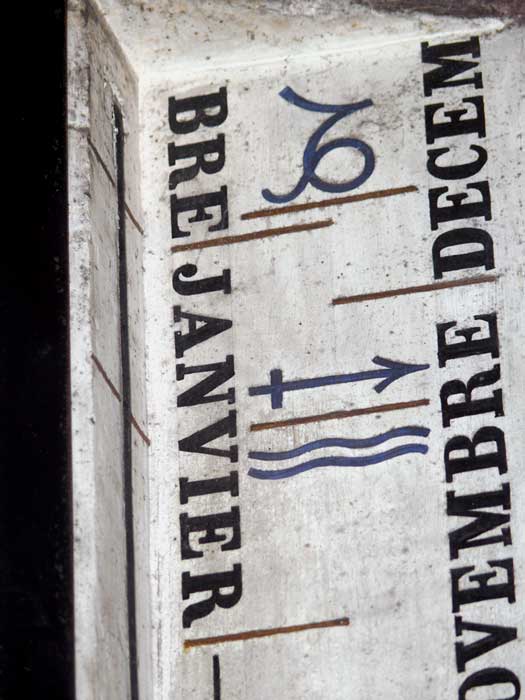

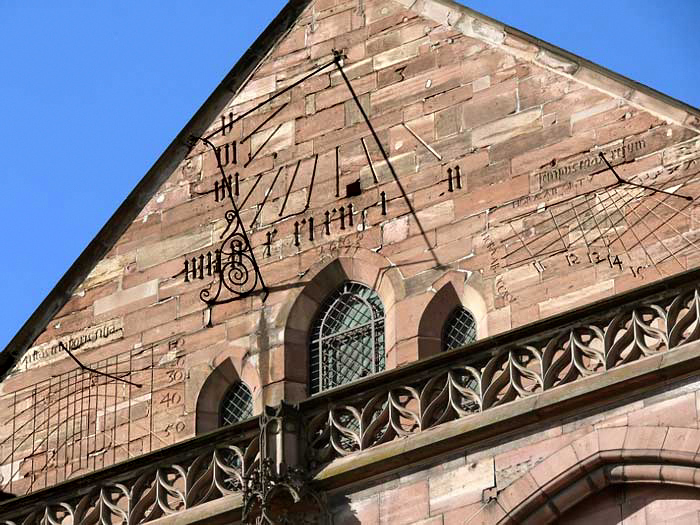

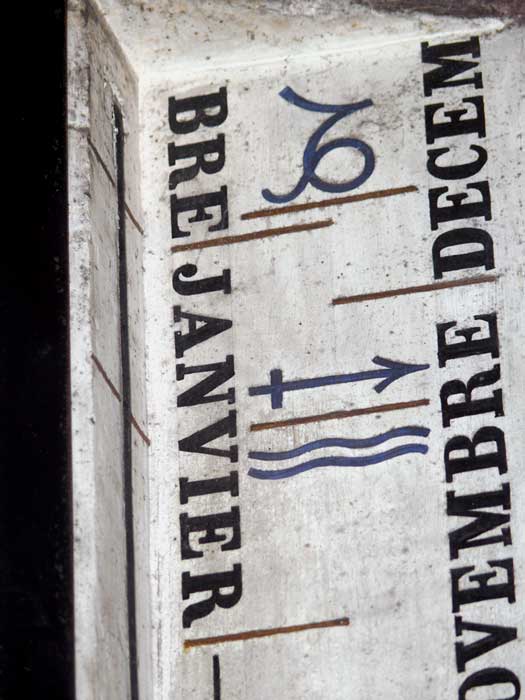

Fig. 3: Heliocentric planetary dial of the third astronomical clock. Photograph © Didier B (Sam67fr), Creative Commons Licence The concern with time that we see in the cathedrals clocks also appears in its fourteen sundials, which date from the 13th to the 18th centuries. The oldest sundial, dated between 1225 and 1235, marks seven times of prayer in the course of the day, beginning at dawn and continuing until sunset. The 15th century saw the addition of three more sundials, dividing the day into twelve hours from sunrise to sunset (Fig. 4). In the 16th century, five dials were installed at the platform level of the tower and three mathematical dials, designed by the builder of the second clock, were installed on the gable of the south transept (Fig. 5). The builder of the 19th-century clock, Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué, installed a vertical meridian line inside the entrance to the south transept (Fig. 6), marking local apparent noon to regulate the clock.

Fig. 4: Astrologer with a sundial, south portal. Photograph © Coyau, Creative Commons Licence

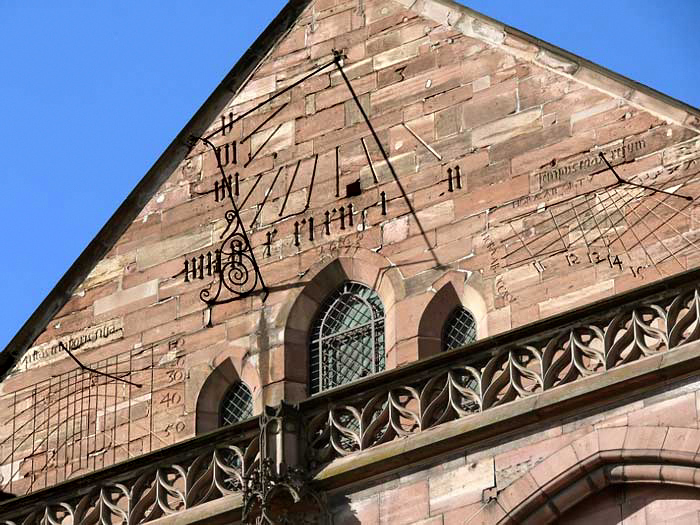

Fig. 5: Three sundials on south gable: altitude/azimuth dial (left), vertical sundial (centre), and dial reading hours from sunrise and sunset (right).

Photograph © Jean-Marie Poncelet, Creative Commons Licence

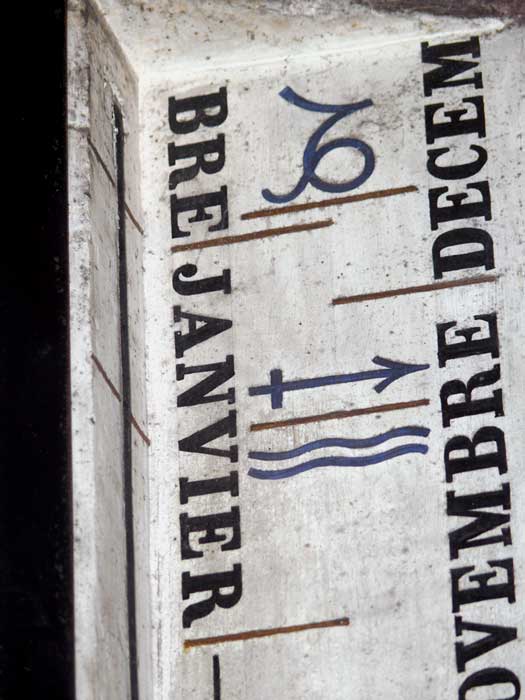

Fig. 6: Schwilligué’s meridian line (detail), inside entrance, south transept. Photograph © Jean-Marie Poncelet, Creative Commons Licence

Cultural and symbolic dimension - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The display of astronomical time was central to the cultural uses of astronomy in medieval Europe. Strasbourg cathedral, which was the ‘principal element of the nomination’ for the World Heritage Site Strasbourg–Grande Île, embodies these astronomical concepts in three ways. Symbolically, the cathedral’s sculptures bind the zodiac to the labours of the months; at a more direct practical level the cathedral displays astronomical time in numerous sundials; and—perhaps most famously—there is the historical sequence of its three great astronomical clocks.

Notwithstanding this, the description of the attributes of value of the property—both in the ‘justification of value’ from the State Party and in the ICOMOS evaluation—takes a classical heritage approach, elucidating this exceptional Gothic church in terms of the history of art, the history of structural design, the history of urban construction, and the history of medieval Christianity, but does not elaborate at all on the astronomical features of the place.

Authenticity and integrity - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral clocks have undergone successive transformations through the centuries; the present 19th-century clock is a development in the tradition of the 14th-century original. Much of the cathedral’s statuary, including two of the sundials, have been replaced by copies; the originals are preserved in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

Management and use

Present use - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral is a place of worship and also a centre of tourism.

State of conservation - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The astronomical elements of the Cathedral are involved in the general conservation management plan of the building. The present state of conservation of these elements is good.

Main threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

Pressures of development and tourism.

Protection - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:34:33

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral was designated a Monument Historique in 1862 and has been part of a World Heritage Site since 1988.

Context and environment - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-05-13 22:05:49

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral is located in a historical, urban environment.

Management, interpretation and outreach - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral provides tours of its major sites, including the clocks and the platform at the tower where some of the more important sundials are located. The Museums have an active program of interpretation of their collections.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:37:59

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

- Oestmann, Günther (1993). Die astronomische Uhr des Straßburger Münsters: Funktion und Bedeutung eines Kosmos-Modells des 16. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart: Verlag für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften und der Technik.

- Poulle, Emmanuel (1983). ’L’horloge planétaire de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg‘, Journal for the History of Astronomy 14, 33-46.

- Schwiligué, Charles (1844). Description abrégée de l’Horloge astronomique de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg. Strasbourg: Imprimerie Dannbach.

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

City of Strasbourg, Département du Bas-Rhin, Alsace region, France.

Location - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:17:03

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

Latitude 48° 34′ 55″ N, longitude 7° 45′ 5″ E. Elevation 150m above mean sea level.

General description - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:21:24

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral of Notre Dame, constructed from the 11th to the 14th centuries, forms the core of this site. Several original timekeepers which have been removed from the cathedral are now in Strasbourg’s Museum of Decorative Arts and Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame. The Cathedral forms part of the World Heritage property Strasbourg-Grande Île inscribed on the List in 1988 under criteria (i), (ii) and (iv).

Brief inventory - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:28:02

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

Inventory of the remains related to astronomy:

Location Description Sundials

Niche in buttress of south transept; original in Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame Statue of youth with a sundial (1225 × 1235) Gable of south transept Three vertical sundials, Conrad Dasypodius (1572) Exterior wall of the Treasury Vertical sundial (1488?) Exterior buttress of the Treasury Vertical sundial (15th century) South transept above clock; original in Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame Relief of astrologer with a sundial (c. 1490) Inside door of south transept Meridian line (1838-42) Tower’s four sides at platform level Four vertical dials (16th century) Tower’s south side at platform level Meridian with triangular stylus and single vertical noon line (16th century) Tower Statue of man holding sundial-like shield with concentric circles (late 15th century) Clocks

South transept, above entrance External clock shows hour of day and day of week (and corresponding planet) Formerly opposite the present clock in the South Transept; cock-automaton in Museum of Decorative Arts First astronomical clock (1352-4) Formerly in the location of the present clock in the south transept; mechanism now in Museum of Decorative Arts Second astronomical clock (1571-4), Conrad Dasypodius In the south transept Third astronomical clock (1838-42), Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué Zodiac

West front, right portal, niches in bases of statues Zodiac and occupations of the months (late 13th-early 14th centuries)

History - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 10

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-08-16 22:09:10

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

With the construction of the west front, the cathedral obtained its earliest known display of astronomical time—one that the cathedral shares with many other large churches—the carved reliefs depicting the signs of the zodiac and the labours of the months in the bases of the statues flanking the right portal (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Occupations of the months and signs of the zodiac, west façade, right portal—May, Gemini; June, Cancer; July, Leo; August, Virgo.

Photograph © Ad Meskens, Creative Commons Licence The most widely known of these astronomical displays of are the cathedral’s elaborate astronomical clocks. The 14th-century clock included a calendar, a mechanically driven stereographic projection showing the movement of the stars, and pointers showing the positions of the Sun and Moon. Atop the clock was an automaton of a cockerel, which crowed at noon, flapping its wings.

The 16th-century clock added to these elements a rotating celestial sphere on which were depicted all 1020 stars of Ptolemy’s star catalogue together with figures of 48 constellations, a disc showing the ecclesiastical calendar for 100 years, and depictions of all eclipses over an interval of 32 years. A stereographic projection of the stars, Sun and Moon, like the one in the original clock, was enhanced with additional pointers showing the positions of all the visible planets and the Dragon, or lunar node, which served to explain eclipses (Fig. 2). Elements of the case and display were incorporated into the current clock. Although the clock reflected the geocentric model of astronomy, its decoration included a portrait of Nicolas Copernicus.

Fig. 2: Astrolabe planetary dial of the second astronomical clock. Detail from Woodcut by Tobias Stimmer (1574) The 19th-century clock reflected Copernican astronomical concepts. The geocentric stereographic projection of the Sun, Moon, and planets was replaced by a heliocentric model of the visible planets, plus the Earth and Moon, in the solar system (Fig. 2b). It displayed both uniform civil time and the apparent time indicated by the daily motions of the Sun. The stellar globe now portrayed more than 5000 stars, extending down to faint sixth magnitude ones. In addition, the clock incorporated a perpetual calendar, computing the solar cycle of 28 years, the lunar cycle of 19 years, the date of Easter, and other calendrical parameters traditionally found in ecclesiastical computus.

Fig. 3: Heliocentric planetary dial of the third astronomical clock. Photograph © Didier B (Sam67fr), Creative Commons Licence The concern with time that we see in the cathedrals clocks also appears in its fourteen sundials, which date from the 13th to the 18th centuries. The oldest sundial, dated between 1225 and 1235, marks seven times of prayer in the course of the day, beginning at dawn and continuing until sunset. The 15th century saw the addition of three more sundials, dividing the day into twelve hours from sunrise to sunset (Fig. 4). In the 16th century, five dials were installed at the platform level of the tower and three mathematical dials, designed by the builder of the second clock, were installed on the gable of the south transept (Fig. 5). The builder of the 19th-century clock, Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué, installed a vertical meridian line inside the entrance to the south transept (Fig. 6), marking local apparent noon to regulate the clock.

Fig. 4: Astrologer with a sundial, south portal. Photograph © Coyau, Creative Commons Licence

Fig. 5: Three sundials on south gable: altitude/azimuth dial (left), vertical sundial (centre), and dial reading hours from sunrise and sunset (right).

Photograph © Jean-Marie Poncelet, Creative Commons Licence

Fig. 6: Schwilligué’s meridian line (detail), inside entrance, south transept. Photograph © Jean-Marie Poncelet, Creative Commons Licence

Cultural and symbolic dimension - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The display of astronomical time was central to the cultural uses of astronomy in medieval Europe. Strasbourg cathedral, which was the ‘principal element of the nomination’ for the World Heritage Site Strasbourg–Grande Île, embodies these astronomical concepts in three ways. Symbolically, the cathedral’s sculptures bind the zodiac to the labours of the months; at a more direct practical level the cathedral displays astronomical time in numerous sundials; and—perhaps most famously—there is the historical sequence of its three great astronomical clocks.

Notwithstanding this, the description of the attributes of value of the property—both in the ‘justification of value’ from the State Party and in the ICOMOS evaluation—takes a classical heritage approach, elucidating this exceptional Gothic church in terms of the history of art, the history of structural design, the history of urban construction, and the history of medieval Christianity, but does not elaborate at all on the astronomical features of the place.

Authenticity and integrity - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral clocks have undergone successive transformations through the centuries; the present 19th-century clock is a development in the tradition of the 14th-century original. Much of the cathedral’s statuary, including two of the sundials, have been replaced by copies; the originals are preserved in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

Management and use

Present use - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral is a place of worship and also a centre of tourism.

State of conservation - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The astronomical elements of the Cathedral are involved in the general conservation management plan of the building. The present state of conservation of these elements is good.

Main threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

Pressures of development and tourism.

Protection - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:34:33

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral was designated a Monument Historique in 1862 and has been part of a World Heritage Site since 1988.

Context and environment - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-05-13 22:05:49

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral is located in a historical, urban environment.

Management, interpretation and outreach - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral provides tours of its major sites, including the clocks and the platform at the tower where some of the more important sundials are located. The Museums have an active program of interpretation of their collections.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:37:59

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

- Oestmann, Günther (1993). Die astronomische Uhr des Straßburger Münsters: Funktion und Bedeutung eines Kosmos-Modells des 16. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart: Verlag für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften und der Technik.

- Poulle, Emmanuel (1983). ’L’horloge planétaire de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg‘, Journal for the History of Astronomy 14, 33-46.

- Schwiligué, Charles (1844). Description abrégée de l’Horloge astronomique de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg. Strasbourg: Imprimerie Dannbach.

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:17:03

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

Latitude 48° 34′ 55″ N, longitude 7° 45′ 5″ E. Elevation 150m above mean sea level.

General description - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:21:24

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral of Notre Dame, constructed from the 11th to the 14th centuries, forms the core of this site. Several original timekeepers which have been removed from the cathedral are now in Strasbourg’s Museum of Decorative Arts and Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame. The Cathedral forms part of the World Heritage property Strasbourg-Grande Île inscribed on the List in 1988 under criteria (i), (ii) and (iv).

Brief inventory - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:28:02

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

Inventory of the remains related to astronomy:

Location Description Sundials

Niche in buttress of south transept; original in Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame Statue of youth with a sundial (1225 × 1235) Gable of south transept Three vertical sundials, Conrad Dasypodius (1572) Exterior wall of the Treasury Vertical sundial (1488?) Exterior buttress of the Treasury Vertical sundial (15th century) South transept above clock; original in Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame Relief of astrologer with a sundial (c. 1490) Inside door of south transept Meridian line (1838-42) Tower’s four sides at platform level Four vertical dials (16th century) Tower’s south side at platform level Meridian with triangular stylus and single vertical noon line (16th century) Tower Statue of man holding sundial-like shield with concentric circles (late 15th century) Clocks

South transept, above entrance External clock shows hour of day and day of week (and corresponding planet) Formerly opposite the present clock in the South Transept; cock-automaton in Museum of Decorative Arts First astronomical clock (1352-4) Formerly in the location of the present clock in the south transept; mechanism now in Museum of Decorative Arts Second astronomical clock (1571-4), Conrad Dasypodius In the south transept Third astronomical clock (1838-42), Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué Zodiac

West front, right portal, niches in bases of statues Zodiac and occupations of the months (late 13th-early 14th centuries)

History - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 10

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-08-16 22:09:10

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

With the construction of the west front, the cathedral obtained its earliest known display of astronomical time—one that the cathedral shares with many other large churches—the carved reliefs depicting the signs of the zodiac and the labours of the months in the bases of the statues flanking the right portal (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Occupations of the months and signs of the zodiac, west façade, right portal—May, Gemini; June, Cancer; July, Leo; August, Virgo.

Photograph © Ad Meskens, Creative Commons Licence The most widely known of these astronomical displays of are the cathedral’s elaborate astronomical clocks. The 14th-century clock included a calendar, a mechanically driven stereographic projection showing the movement of the stars, and pointers showing the positions of the Sun and Moon. Atop the clock was an automaton of a cockerel, which crowed at noon, flapping its wings.

The 16th-century clock added to these elements a rotating celestial sphere on which were depicted all 1020 stars of Ptolemy’s star catalogue together with figures of 48 constellations, a disc showing the ecclesiastical calendar for 100 years, and depictions of all eclipses over an interval of 32 years. A stereographic projection of the stars, Sun and Moon, like the one in the original clock, was enhanced with additional pointers showing the positions of all the visible planets and the Dragon, or lunar node, which served to explain eclipses (Fig. 2). Elements of the case and display were incorporated into the current clock. Although the clock reflected the geocentric model of astronomy, its decoration included a portrait of Nicolas Copernicus.

Fig. 2: Astrolabe planetary dial of the second astronomical clock. Detail from Woodcut by Tobias Stimmer (1574) The 19th-century clock reflected Copernican astronomical concepts. The geocentric stereographic projection of the Sun, Moon, and planets was replaced by a heliocentric model of the visible planets, plus the Earth and Moon, in the solar system (Fig. 2b). It displayed both uniform civil time and the apparent time indicated by the daily motions of the Sun. The stellar globe now portrayed more than 5000 stars, extending down to faint sixth magnitude ones. In addition, the clock incorporated a perpetual calendar, computing the solar cycle of 28 years, the lunar cycle of 19 years, the date of Easter, and other calendrical parameters traditionally found in ecclesiastical computus.

Fig. 3: Heliocentric planetary dial of the third astronomical clock. Photograph © Didier B (Sam67fr), Creative Commons Licence The concern with time that we see in the cathedrals clocks also appears in its fourteen sundials, which date from the 13th to the 18th centuries. The oldest sundial, dated between 1225 and 1235, marks seven times of prayer in the course of the day, beginning at dawn and continuing until sunset. The 15th century saw the addition of three more sundials, dividing the day into twelve hours from sunrise to sunset (Fig. 4). In the 16th century, five dials were installed at the platform level of the tower and three mathematical dials, designed by the builder of the second clock, were installed on the gable of the south transept (Fig. 5). The builder of the 19th-century clock, Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué, installed a vertical meridian line inside the entrance to the south transept (Fig. 6), marking local apparent noon to regulate the clock.

Fig. 4: Astrologer with a sundial, south portal. Photograph © Coyau, Creative Commons Licence

Fig. 5: Three sundials on south gable: altitude/azimuth dial (left), vertical sundial (centre), and dial reading hours from sunrise and sunset (right).

Photograph © Jean-Marie Poncelet, Creative Commons Licence

Fig. 6: Schwilligué’s meridian line (detail), inside entrance, south transept. Photograph © Jean-Marie Poncelet, Creative Commons Licence

Cultural and symbolic dimension - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The display of astronomical time was central to the cultural uses of astronomy in medieval Europe. Strasbourg cathedral, which was the ‘principal element of the nomination’ for the World Heritage Site Strasbourg–Grande Île, embodies these astronomical concepts in three ways. Symbolically, the cathedral’s sculptures bind the zodiac to the labours of the months; at a more direct practical level the cathedral displays astronomical time in numerous sundials; and—perhaps most famously—there is the historical sequence of its three great astronomical clocks.

Notwithstanding this, the description of the attributes of value of the property—both in the ‘justification of value’ from the State Party and in the ICOMOS evaluation—takes a classical heritage approach, elucidating this exceptional Gothic church in terms of the history of art, the history of structural design, the history of urban construction, and the history of medieval Christianity, but does not elaborate at all on the astronomical features of the place.

Authenticity and integrity - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral clocks have undergone successive transformations through the centuries; the present 19th-century clock is a development in the tradition of the 14th-century original. Much of the cathedral’s statuary, including two of the sundials, have been replaced by copies; the originals are preserved in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

Management and use

Present use - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral is a place of worship and also a centre of tourism.

State of conservation - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The astronomical elements of the Cathedral are involved in the general conservation management plan of the building. The present state of conservation of these elements is good.

Main threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

Pressures of development and tourism.

Protection - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:34:33

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral was designated a Monument Historique in 1862 and has been part of a World Heritage Site since 1988.

Context and environment - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-05-13 22:05:49

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral is located in a historical, urban environment.

Management, interpretation and outreach - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral provides tours of its major sites, including the clocks and the platform at the tower where some of the more important sundials are located. The Museums have an active program of interpretation of their collections.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:37:59

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

- Oestmann, Günther (1993). Die astronomische Uhr des Straßburger Münsters: Funktion und Bedeutung eines Kosmos-Modells des 16. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart: Verlag für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften und der Technik.

- Poulle, Emmanuel (1983). ’L’horloge planétaire de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg‘, Journal for the History of Astronomy 14, 33-46.

- Schwiligué, Charles (1844). Description abrégée de l’Horloge astronomique de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg. Strasbourg: Imprimerie Dannbach.

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:21:24

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral of Notre Dame, constructed from the 11th to the 14th centuries, forms the core of this site. Several original timekeepers which have been removed from the cathedral are now in Strasbourg’s Museum of Decorative Arts and Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame. The Cathedral forms part of the World Heritage property Strasbourg-Grande Île inscribed on the List in 1988 under criteria (i), (ii) and (iv).

Brief inventory - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:28:02

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

Inventory of the remains related to astronomy:

Location Description Sundials

Niche in buttress of south transept; original in Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame Statue of youth with a sundial (1225 × 1235) Gable of south transept Three vertical sundials, Conrad Dasypodius (1572) Exterior wall of the Treasury Vertical sundial (1488?) Exterior buttress of the Treasury Vertical sundial (15th century) South transept above clock; original in Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame Relief of astrologer with a sundial (c. 1490) Inside door of south transept Meridian line (1838-42) Tower’s four sides at platform level Four vertical dials (16th century) Tower’s south side at platform level Meridian with triangular stylus and single vertical noon line (16th century) Tower Statue of man holding sundial-like shield with concentric circles (late 15th century) Clocks

South transept, above entrance External clock shows hour of day and day of week (and corresponding planet) Formerly opposite the present clock in the South Transept; cock-automaton in Museum of Decorative Arts First astronomical clock (1352-4) Formerly in the location of the present clock in the south transept; mechanism now in Museum of Decorative Arts Second astronomical clock (1571-4), Conrad Dasypodius In the south transept Third astronomical clock (1838-42), Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué Zodiac

West front, right portal, niches in bases of statues Zodiac and occupations of the months (late 13th-early 14th centuries)

History - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 10

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-08-16 22:09:10

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

With the construction of the west front, the cathedral obtained its earliest known display of astronomical time—one that the cathedral shares with many other large churches—the carved reliefs depicting the signs of the zodiac and the labours of the months in the bases of the statues flanking the right portal (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Occupations of the months and signs of the zodiac, west façade, right portal—May, Gemini; June, Cancer; July, Leo; August, Virgo.

Photograph © Ad Meskens, Creative Commons Licence The most widely known of these astronomical displays of are the cathedral’s elaborate astronomical clocks. The 14th-century clock included a calendar, a mechanically driven stereographic projection showing the movement of the stars, and pointers showing the positions of the Sun and Moon. Atop the clock was an automaton of a cockerel, which crowed at noon, flapping its wings.

The 16th-century clock added to these elements a rotating celestial sphere on which were depicted all 1020 stars of Ptolemy’s star catalogue together with figures of 48 constellations, a disc showing the ecclesiastical calendar for 100 years, and depictions of all eclipses over an interval of 32 years. A stereographic projection of the stars, Sun and Moon, like the one in the original clock, was enhanced with additional pointers showing the positions of all the visible planets and the Dragon, or lunar node, which served to explain eclipses (Fig. 2). Elements of the case and display were incorporated into the current clock. Although the clock reflected the geocentric model of astronomy, its decoration included a portrait of Nicolas Copernicus.

Fig. 2: Astrolabe planetary dial of the second astronomical clock. Detail from Woodcut by Tobias Stimmer (1574) The 19th-century clock reflected Copernican astronomical concepts. The geocentric stereographic projection of the Sun, Moon, and planets was replaced by a heliocentric model of the visible planets, plus the Earth and Moon, in the solar system (Fig. 2b). It displayed both uniform civil time and the apparent time indicated by the daily motions of the Sun. The stellar globe now portrayed more than 5000 stars, extending down to faint sixth magnitude ones. In addition, the clock incorporated a perpetual calendar, computing the solar cycle of 28 years, the lunar cycle of 19 years, the date of Easter, and other calendrical parameters traditionally found in ecclesiastical computus.

Fig. 3: Heliocentric planetary dial of the third astronomical clock. Photograph © Didier B (Sam67fr), Creative Commons Licence The concern with time that we see in the cathedrals clocks also appears in its fourteen sundials, which date from the 13th to the 18th centuries. The oldest sundial, dated between 1225 and 1235, marks seven times of prayer in the course of the day, beginning at dawn and continuing until sunset. The 15th century saw the addition of three more sundials, dividing the day into twelve hours from sunrise to sunset (Fig. 4). In the 16th century, five dials were installed at the platform level of the tower and three mathematical dials, designed by the builder of the second clock, were installed on the gable of the south transept (Fig. 5). The builder of the 19th-century clock, Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué, installed a vertical meridian line inside the entrance to the south transept (Fig. 6), marking local apparent noon to regulate the clock.

Fig. 4: Astrologer with a sundial, south portal. Photograph © Coyau, Creative Commons Licence

Fig. 5: Three sundials on south gable: altitude/azimuth dial (left), vertical sundial (centre), and dial reading hours from sunrise and sunset (right).

Photograph © Jean-Marie Poncelet, Creative Commons Licence

Fig. 6: Schwilligué’s meridian line (detail), inside entrance, south transept. Photograph © Jean-Marie Poncelet, Creative Commons Licence

Cultural and symbolic dimension - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The display of astronomical time was central to the cultural uses of astronomy in medieval Europe. Strasbourg cathedral, which was the ‘principal element of the nomination’ for the World Heritage Site Strasbourg–Grande Île, embodies these astronomical concepts in three ways. Symbolically, the cathedral’s sculptures bind the zodiac to the labours of the months; at a more direct practical level the cathedral displays astronomical time in numerous sundials; and—perhaps most famously—there is the historical sequence of its three great astronomical clocks.

Notwithstanding this, the description of the attributes of value of the property—both in the ‘justification of value’ from the State Party and in the ICOMOS evaluation—takes a classical heritage approach, elucidating this exceptional Gothic church in terms of the history of art, the history of structural design, the history of urban construction, and the history of medieval Christianity, but does not elaborate at all on the astronomical features of the place.

Authenticity and integrity - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral clocks have undergone successive transformations through the centuries; the present 19th-century clock is a development in the tradition of the 14th-century original. Much of the cathedral’s statuary, including two of the sundials, have been replaced by copies; the originals are preserved in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

Management and use

Present use - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral is a place of worship and also a centre of tourism.

State of conservation - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The astronomical elements of the Cathedral are involved in the general conservation management plan of the building. The present state of conservation of these elements is good.

Main threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

Pressures of development and tourism.

Protection - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:34:33

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral was designated a Monument Historique in 1862 and has been part of a World Heritage Site since 1988.

Context and environment - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-05-13 22:05:49

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral is located in a historical, urban environment.

Management, interpretation and outreach - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral provides tours of its major sites, including the clocks and the platform at the tower where some of the more important sundials are located. The Museums have an active program of interpretation of their collections.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:37:59

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

- Oestmann, Günther (1993). Die astronomische Uhr des Straßburger Münsters: Funktion und Bedeutung eines Kosmos-Modells des 16. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart: Verlag für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften und der Technik.

- Poulle, Emmanuel (1983). ’L’horloge planétaire de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg‘, Journal for the History of Astronomy 14, 33-46.

- Schwiligué, Charles (1844). Description abrégée de l’Horloge astronomique de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg. Strasbourg: Imprimerie Dannbach.

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:28:02

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

Inventory of the remains related to astronomy:

| Location | Description |

|---|---|

Sundials | |

| Niche in buttress of south transept; original in Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame | Statue of youth with a sundial (1225 × 1235) |

| Gable of south transept | Three vertical sundials, Conrad Dasypodius (1572) |

| Exterior wall of the Treasury | Vertical sundial (1488?) |

| Exterior buttress of the Treasury | Vertical sundial (15th century) |

| South transept above clock; original in Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame | Relief of astrologer with a sundial (c. 1490) |

| Inside door of south transept | Meridian line (1838-42) |

| Tower’s four sides at platform level | Four vertical dials (16th century) |

| Tower’s south side at platform level | Meridian with triangular stylus and single vertical noon line (16th century) |

| Tower | Statue of man holding sundial-like shield with concentric circles (late 15th century) |

Clocks | |

| South transept, above entrance | External clock shows hour of day and day of week (and corresponding planet) |

| Formerly opposite the present clock in the South Transept; cock-automaton in Museum of Decorative Arts | First astronomical clock (1352-4) |

| Formerly in the location of the present clock in the south transept; mechanism now in Museum of Decorative Arts | Second astronomical clock (1571-4), Conrad Dasypodius |

| In the south transept | Third astronomical clock (1838-42), Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué |

Zodiac | |

| West front, right portal, niches in bases of statues | Zodiac and occupations of the months (late 13th-early 14th centuries) |

History - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 10

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-08-16 22:09:10

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

With the construction of the west front, the cathedral obtained its earliest known display of astronomical time—one that the cathedral shares with many other large churches—the carved reliefs depicting the signs of the zodiac and the labours of the months in the bases of the statues flanking the right portal (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Occupations of the months and signs of the zodiac, west façade, right portal—May, Gemini; June, Cancer; July, Leo; August, Virgo.

Photograph © Ad Meskens, Creative Commons Licence The most widely known of these astronomical displays of are the cathedral’s elaborate astronomical clocks. The 14th-century clock included a calendar, a mechanically driven stereographic projection showing the movement of the stars, and pointers showing the positions of the Sun and Moon. Atop the clock was an automaton of a cockerel, which crowed at noon, flapping its wings.

The 16th-century clock added to these elements a rotating celestial sphere on which were depicted all 1020 stars of Ptolemy’s star catalogue together with figures of 48 constellations, a disc showing the ecclesiastical calendar for 100 years, and depictions of all eclipses over an interval of 32 years. A stereographic projection of the stars, Sun and Moon, like the one in the original clock, was enhanced with additional pointers showing the positions of all the visible planets and the Dragon, or lunar node, which served to explain eclipses (Fig. 2). Elements of the case and display were incorporated into the current clock. Although the clock reflected the geocentric model of astronomy, its decoration included a portrait of Nicolas Copernicus.

Fig. 2: Astrolabe planetary dial of the second astronomical clock. Detail from Woodcut by Tobias Stimmer (1574) The 19th-century clock reflected Copernican astronomical concepts. The geocentric stereographic projection of the Sun, Moon, and planets was replaced by a heliocentric model of the visible planets, plus the Earth and Moon, in the solar system (Fig. 2b). It displayed both uniform civil time and the apparent time indicated by the daily motions of the Sun. The stellar globe now portrayed more than 5000 stars, extending down to faint sixth magnitude ones. In addition, the clock incorporated a perpetual calendar, computing the solar cycle of 28 years, the lunar cycle of 19 years, the date of Easter, and other calendrical parameters traditionally found in ecclesiastical computus.

Fig. 3: Heliocentric planetary dial of the third astronomical clock. Photograph © Didier B (Sam67fr), Creative Commons Licence The concern with time that we see in the cathedrals clocks also appears in its fourteen sundials, which date from the 13th to the 18th centuries. The oldest sundial, dated between 1225 and 1235, marks seven times of prayer in the course of the day, beginning at dawn and continuing until sunset. The 15th century saw the addition of three more sundials, dividing the day into twelve hours from sunrise to sunset (Fig. 4). In the 16th century, five dials were installed at the platform level of the tower and three mathematical dials, designed by the builder of the second clock, were installed on the gable of the south transept (Fig. 5). The builder of the 19th-century clock, Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué, installed a vertical meridian line inside the entrance to the south transept (Fig. 6), marking local apparent noon to regulate the clock.

Fig. 4: Astrologer with a sundial, south portal. Photograph © Coyau, Creative Commons Licence

Fig. 5: Three sundials on south gable: altitude/azimuth dial (left), vertical sundial (centre), and dial reading hours from sunrise and sunset (right).

Photograph © Jean-Marie Poncelet, Creative Commons Licence

Fig. 6: Schwilligué’s meridian line (detail), inside entrance, south transept. Photograph © Jean-Marie Poncelet, Creative Commons Licence

Cultural and symbolic dimension - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The display of astronomical time was central to the cultural uses of astronomy in medieval Europe. Strasbourg cathedral, which was the ‘principal element of the nomination’ for the World Heritage Site Strasbourg–Grande Île, embodies these astronomical concepts in three ways. Symbolically, the cathedral’s sculptures bind the zodiac to the labours of the months; at a more direct practical level the cathedral displays astronomical time in numerous sundials; and—perhaps most famously—there is the historical sequence of its three great astronomical clocks.

Notwithstanding this, the description of the attributes of value of the property—both in the ‘justification of value’ from the State Party and in the ICOMOS evaluation—takes a classical heritage approach, elucidating this exceptional Gothic church in terms of the history of art, the history of structural design, the history of urban construction, and the history of medieval Christianity, but does not elaborate at all on the astronomical features of the place.

Authenticity and integrity - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral clocks have undergone successive transformations through the centuries; the present 19th-century clock is a development in the tradition of the 14th-century original. Much of the cathedral’s statuary, including two of the sundials, have been replaced by copies; the originals are preserved in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

Management and use

Present use - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral is a place of worship and also a centre of tourism.

State of conservation - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The astronomical elements of the Cathedral are involved in the general conservation management plan of the building. The present state of conservation of these elements is good.

Main threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

Pressures of development and tourism.

Protection - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:34:33

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral was designated a Monument Historique in 1862 and has been part of a World Heritage Site since 1988.

Context and environment - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-05-13 22:05:49

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral is located in a historical, urban environment.

Management, interpretation and outreach - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral provides tours of its major sites, including the clocks and the platform at the tower where some of the more important sundials are located. The Museums have an active program of interpretation of their collections.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:37:59

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

- Oestmann, Günther (1993). Die astronomische Uhr des Straßburger Münsters: Funktion und Bedeutung eines Kosmos-Modells des 16. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart: Verlag für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften und der Technik.

- Poulle, Emmanuel (1983). ’L’horloge planétaire de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg‘, Journal for the History of Astronomy 14, 33-46.

- Schwiligué, Charles (1844). Description abrégée de l’Horloge astronomique de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg. Strasbourg: Imprimerie Dannbach.

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 10

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-08-16 22:09:10

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

With the construction of the west front, the cathedral obtained its earliest known display of astronomical time—one that the cathedral shares with many other large churches—the carved reliefs depicting the signs of the zodiac and the labours of the months in the bases of the statues flanking the right portal (Fig. 1).

Photograph © Ad Meskens, Creative Commons Licence

The most widely known of these astronomical displays of are the cathedral’s elaborate astronomical clocks. The 14th-century clock included a calendar, a mechanically driven stereographic projection showing the movement of the stars, and pointers showing the positions of the Sun and Moon. Atop the clock was an automaton of a cockerel, which crowed at noon, flapping its wings.

The 16th-century clock added to these elements a rotating celestial sphere on which were depicted all 1020 stars of Ptolemy’s star catalogue together with figures of 48 constellations, a disc showing the ecclesiastical calendar for 100 years, and depictions of all eclipses over an interval of 32 years. A stereographic projection of the stars, Sun and Moon, like the one in the original clock, was enhanced with additional pointers showing the positions of all the visible planets and the Dragon, or lunar node, which served to explain eclipses (Fig. 2). Elements of the case and display were incorporated into the current clock. Although the clock reflected the geocentric model of astronomy, its decoration included a portrait of Nicolas Copernicus.

The 19th-century clock reflected Copernican astronomical concepts. The geocentric stereographic projection of the Sun, Moon, and planets was replaced by a heliocentric model of the visible planets, plus the Earth and Moon, in the solar system (Fig. 2b). It displayed both uniform civil time and the apparent time indicated by the daily motions of the Sun. The stellar globe now portrayed more than 5000 stars, extending down to faint sixth magnitude ones. In addition, the clock incorporated a perpetual calendar, computing the solar cycle of 28 years, the lunar cycle of 19 years, the date of Easter, and other calendrical parameters traditionally found in ecclesiastical computus.

The concern with time that we see in the cathedrals clocks also appears in its fourteen sundials, which date from the 13th to the 18th centuries. The oldest sundial, dated between 1225 and 1235, marks seven times of prayer in the course of the day, beginning at dawn and continuing until sunset. The 15th century saw the addition of three more sundials, dividing the day into twelve hours from sunrise to sunset (Fig. 4). In the 16th century, five dials were installed at the platform level of the tower and three mathematical dials, designed by the builder of the second clock, were installed on the gable of the south transept (Fig. 5). The builder of the 19th-century clock, Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué, installed a vertical meridian line inside the entrance to the south transept (Fig. 6), marking local apparent noon to regulate the clock.

Photograph © Jean-Marie Poncelet, Creative Commons Licence

Cultural and symbolic dimension - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The display of astronomical time was central to the cultural uses of astronomy in medieval Europe. Strasbourg cathedral, which was the ‘principal element of the nomination’ for the World Heritage Site Strasbourg–Grande Île, embodies these astronomical concepts in three ways. Symbolically, the cathedral’s sculptures bind the zodiac to the labours of the months; at a more direct practical level the cathedral displays astronomical time in numerous sundials; and—perhaps most famously—there is the historical sequence of its three great astronomical clocks.

Notwithstanding this, the description of the attributes of value of the property—both in the ‘justification of value’ from the State Party and in the ICOMOS evaluation—takes a classical heritage approach, elucidating this exceptional Gothic church in terms of the history of art, the history of structural design, the history of urban construction, and the history of medieval Christianity, but does not elaborate at all on the astronomical features of the place.

Authenticity and integrity - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral clocks have undergone successive transformations through the centuries; the present 19th-century clock is a development in the tradition of the 14th-century original. Much of the cathedral’s statuary, including two of the sundials, have been replaced by copies; the originals are preserved in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

Management and use

Present use - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral is a place of worship and also a centre of tourism.

State of conservation - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The astronomical elements of the Cathedral are involved in the general conservation management plan of the building. The present state of conservation of these elements is good.

Main threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

Pressures of development and tourism.

Protection - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:34:33

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral was designated a Monument Historique in 1862 and has been part of a World Heritage Site since 1988.

Context and environment - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-05-13 22:05:49

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral is located in a historical, urban environment.

Management, interpretation and outreach - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral provides tours of its major sites, including the clocks and the platform at the tower where some of the more important sundials are located. The Museums have an active program of interpretation of their collections.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:37:59

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

- Oestmann, Günther (1993). Die astronomische Uhr des Straßburger Münsters: Funktion und Bedeutung eines Kosmos-Modells des 16. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart: Verlag für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften und der Technik.

- Poulle, Emmanuel (1983). ’L’horloge planétaire de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg‘, Journal for the History of Astronomy 14, 33-46.

- Schwiligué, Charles (1844). Description abrégée de l’Horloge astronomique de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg. Strasbourg: Imprimerie Dannbach.

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The display of astronomical time was central to the cultural uses of astronomy in medieval Europe. Strasbourg cathedral, which was the ‘principal element of the nomination’ for the World Heritage Site Strasbourg–Grande Île, embodies these astronomical concepts in three ways. Symbolically, the cathedral’s sculptures bind the zodiac to the labours of the months; at a more direct practical level the cathedral displays astronomical time in numerous sundials; and—perhaps most famously—there is the historical sequence of its three great astronomical clocks.

Notwithstanding this, the description of the attributes of value of the property—both in the ‘justification of value’ from the State Party and in the ICOMOS evaluation—takes a classical heritage approach, elucidating this exceptional Gothic church in terms of the history of art, the history of structural design, the history of urban construction, and the history of medieval Christianity, but does not elaborate at all on the astronomical features of the place.

Authenticity and integrity - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral clocks have undergone successive transformations through the centuries; the present 19th-century clock is a development in the tradition of the 14th-century original. Much of the cathedral’s statuary, including two of the sundials, have been replaced by copies; the originals are preserved in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

Management and use

Present use - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral is a place of worship and also a centre of tourism.

State of conservation - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The astronomical elements of the Cathedral are involved in the general conservation management plan of the building. The present state of conservation of these elements is good.

Main threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

Pressures of development and tourism.

Protection - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:34:33

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral was designated a Monument Historique in 1862 and has been part of a World Heritage Site since 1988.

Context and environment - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-05-13 22:05:49

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral is located in a historical, urban environment.

Management, interpretation and outreach - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral provides tours of its major sites, including the clocks and the platform at the tower where some of the more important sundials are located. The Museums have an active program of interpretation of their collections.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:37:59

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

- Oestmann, Günther (1993). Die astronomische Uhr des Straßburger Münsters: Funktion und Bedeutung eines Kosmos-Modells des 16. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart: Verlag für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften und der Technik.

- Poulle, Emmanuel (1983). ’L’horloge planétaire de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg‘, Journal for the History of Astronomy 14, 33-46.

- Schwiligué, Charles (1844). Description abrégée de l’Horloge astronomique de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg. Strasbourg: Imprimerie Dannbach.

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral clocks have undergone successive transformations through the centuries; the present 19th-century clock is a development in the tradition of the 14th-century original. Much of the cathedral’s statuary, including two of the sundials, have been replaced by copies; the originals are preserved in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

Management and use

Present use - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral is a place of worship and also a centre of tourism.

State of conservation - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The astronomical elements of the Cathedral are involved in the general conservation management plan of the building. The present state of conservation of these elements is good.

Main threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

Pressures of development and tourism.

Protection - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:34:33

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral was designated a Monument Historique in 1862 and has been part of a World Heritage Site since 1988.

Context and environment - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-05-13 22:05:49

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral is located in a historical, urban environment.

Management, interpretation and outreach - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral provides tours of its major sites, including the clocks and the platform at the tower where some of the more important sundials are located. The Museums have an active program of interpretation of their collections.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:37:59

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

- Oestmann, Günther (1993). Die astronomische Uhr des Straßburger Münsters: Funktion und Bedeutung eines Kosmos-Modells des 16. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart: Verlag für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften und der Technik.

- Poulle, Emmanuel (1983). ’L’horloge planétaire de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg‘, Journal for the History of Astronomy 14, 33-46.

- Schwiligué, Charles (1844). Description abrégée de l’Horloge astronomique de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg. Strasbourg: Imprimerie Dannbach.

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral is a place of worship and also a centre of tourism.

State of conservation - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The astronomical elements of the Cathedral are involved in the general conservation management plan of the building. The present state of conservation of these elements is good.

Main threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

Pressures of development and tourism.

Protection - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:34:33

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral was designated a Monument Historique in 1862 and has been part of a World Heritage Site since 1988.

Context and environment - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-05-13 22:05:49

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral is located in a historical, urban environment.

Management, interpretation and outreach - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral provides tours of its major sites, including the clocks and the platform at the tower where some of the more important sundials are located. The Museums have an active program of interpretation of their collections.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:37:59

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

- Oestmann, Günther (1993). Die astronomische Uhr des Straßburger Münsters: Funktion und Bedeutung eines Kosmos-Modells des 16. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart: Verlag für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften und der Technik.

- Poulle, Emmanuel (1983). ’L’horloge planétaire de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg‘, Journal for the History of Astronomy 14, 33-46.

- Schwiligué, Charles (1844). Description abrégée de l’Horloge astronomique de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg. Strasbourg: Imprimerie Dannbach.

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The astronomical elements of the Cathedral are involved in the general conservation management plan of the building. The present state of conservation of these elements is good.

Main threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

Pressures of development and tourism.

Protection - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:34:33

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral was designated a Monument Historique in 1862 and has been part of a World Heritage Site since 1988.

Context and environment - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-05-13 22:05:49

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

The Cathedral is located in a historical, urban environment.

Management, interpretation and outreach - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

The Cathedral provides tours of its major sites, including the clocks and the platform at the tower where some of the more important sundials are located. The Museums have an active program of interpretation of their collections.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2012-04-30 13:37:59

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey with contributions by Clive Ruggles

- Oestmann, Günther (1993). Die astronomische Uhr des Straßburger Münsters: Funktion und Bedeutung eines Kosmos-Modells des 16. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart: Verlag für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften und der Technik.

- Poulle, Emmanuel (1983). ’L’horloge planétaire de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg‘, Journal for the History of Astronomy 14, 33-46.

- Schwiligué, Charles (1844). Description abrégée de l’Horloge astronomique de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg. Strasbourg: Imprimerie Dannbach.

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2011-08-22 11:08:01

Author(s): Stephen McCluskey

Pressures of development and tourism.

Protection - InfoTheme: Medieval astronomy in Europe

Entity: 33