Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Landessternwarte Heidelberg, Germany

Format: IAU - Outstanding Astronomical Heritage

Description

Geographical position - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-20 14:33:16

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Heidelberg-Königstuhl State Observatory (Landessternwarte Heidelberg-Königstuhl),

Center for Astronomy (ZAH) at the University of Heidelberg,

Königstuhl 12, D-69117 Heidelberg, Germany

Additional places connected to astronomy in Heidelberg:

- Max Wolf’s birthplace and private observatory, Märzgasse 16

- Laboratory of Kirchhoff and Bunsen (1858), "Haus zum Riesen", Johann Adam Breunig (1707/08), Hauptstr. 52

- Bergfriedhof, Grab Max Wolf, Rundweg IV, 26.

Location - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-20 14:34:37

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude 49°23’54’’ N, Longitude 08°43’29’’ E, Elevation 566m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-08-17 10:23:20

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

024

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 16

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-05-25 18:42:01

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 1a. Laboratory of Kirchhoff and Bunsen (1858), Hauptstr. 52 (DChG)

Fig. 1b. Laboratory of Kirchhoff and Bunsen (1858), "Haus zum Riesen", Johann Adam Breunig (1707/08), Hauptstr. 52 (Wikipedia)

In Heidelberg, the method of spectral analysis was invented by Kirchhoff and Bunsen (1859); their Laboratory was since 1868 in the "Haus zum Riesen", Johann Adam Breunig (1707/08), Hauptstr. 52.

Max Wolf’s private observatory, Märzgasse 16

Fig. 2a. Max Wolf’s birthplace, Märzgasse 16 (Wikipedia, CC4, Ribax)

Fig. 2b. Max Wolf’s private observatory, Märzgasse 16 (1885), (Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Heid. Hs. 3695/B,5, Nachlass Max Wolf 0179)

Fig. 2c. Max Wolf’s private observatory, Märzgasse 16 (1885), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

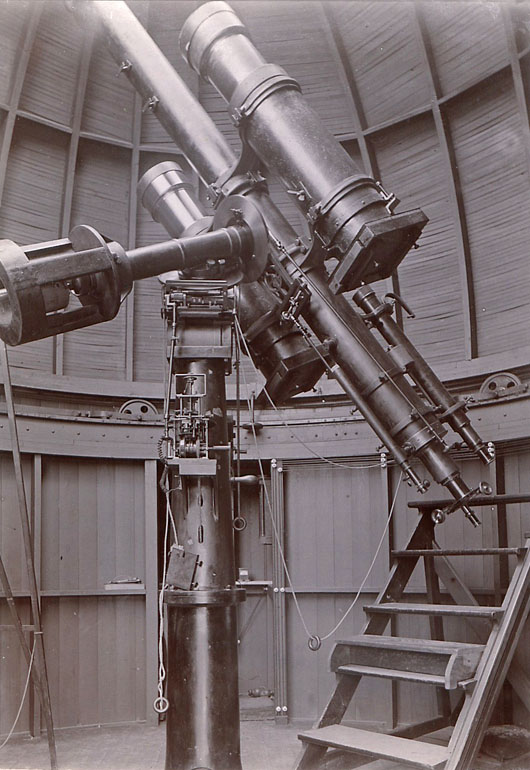

Fig. 2d. 6-inch-Astrograph - two portrait cameras (1892/93) in the white dome in Königsstuhl (Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Heid. Hs. 3695)

Fig. 2e. Max Wolf’s private observatory, 6-inch-Double Astrograph, consisting of two portrait cameras, made by Voigtländer of Braunschweig (1892), now as a museum object in Heidelberg-Königsstuhl Observatory (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Max Wolf’s birthplace, built in 1836, and private observatory (1885) can be found in Märzgasse 16 in Heidelberg.

The double astrograph was put into operation by Max Wolf in February 1892. The astrograph consisted of two 6-inch-portrait lenses made by Voigtländer of Braunschweig. They had an aperture ratio of f/5. The field of view was approximately 70 square degrees and thus covered an unusually large section of the sky for that time. The guiding telescope was used for tracking during the recordings. With this instrument, Max Wolf discovered, among other things, the North American nebula NGC7000 and many new minor planets (planetoids, asteroids). Minor planets revealed themselves on the exposed photographic plates by small traces of lines, due to their own motion during the relatively long exposure time, which could well be a few hours.

Wolf’s instruments, the double astrograph, consisting of two portrait cameras and a guiding telescope, are preserved in Heidelberg-Königsstuhl Observatory.

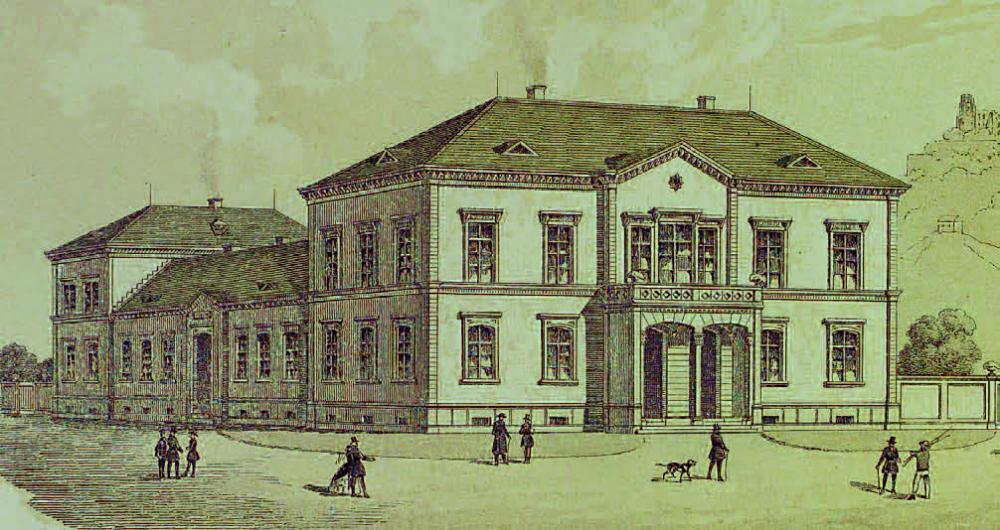

Großherzogliche Bergsternwarte / Landessternwarte Heidelberg

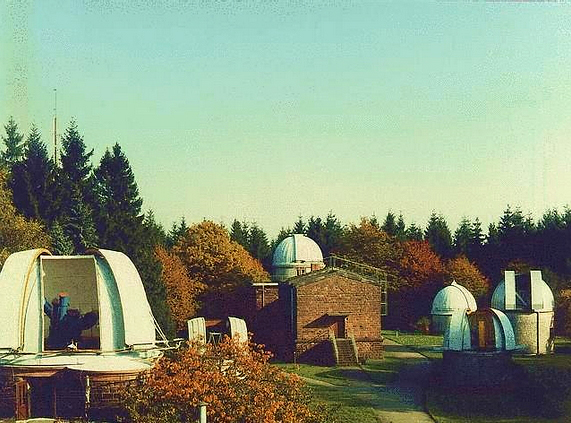

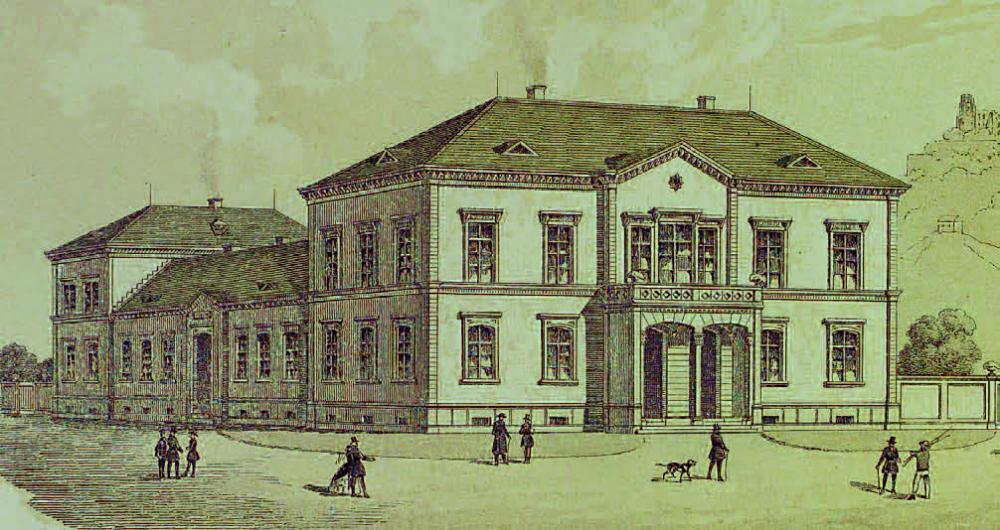

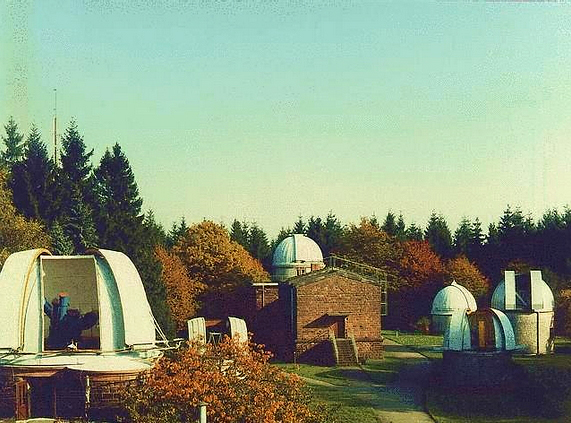

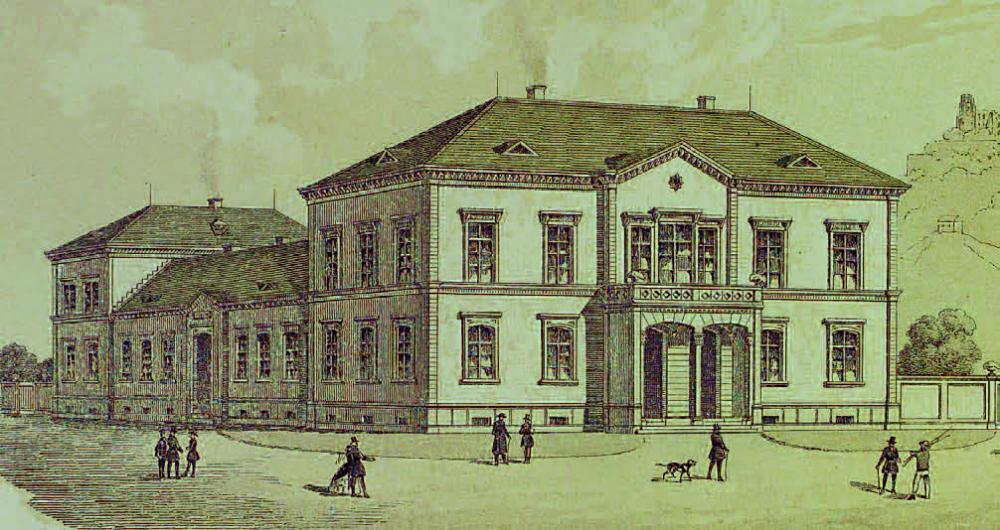

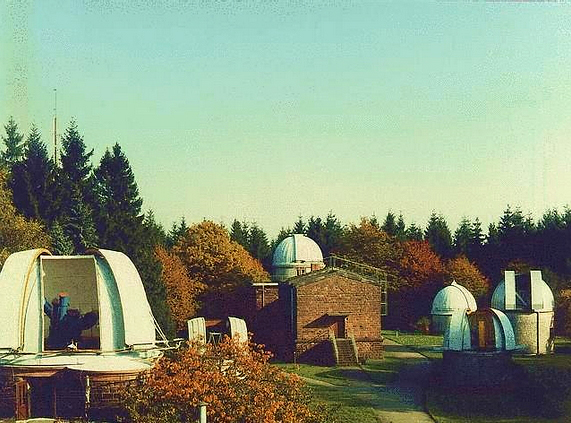

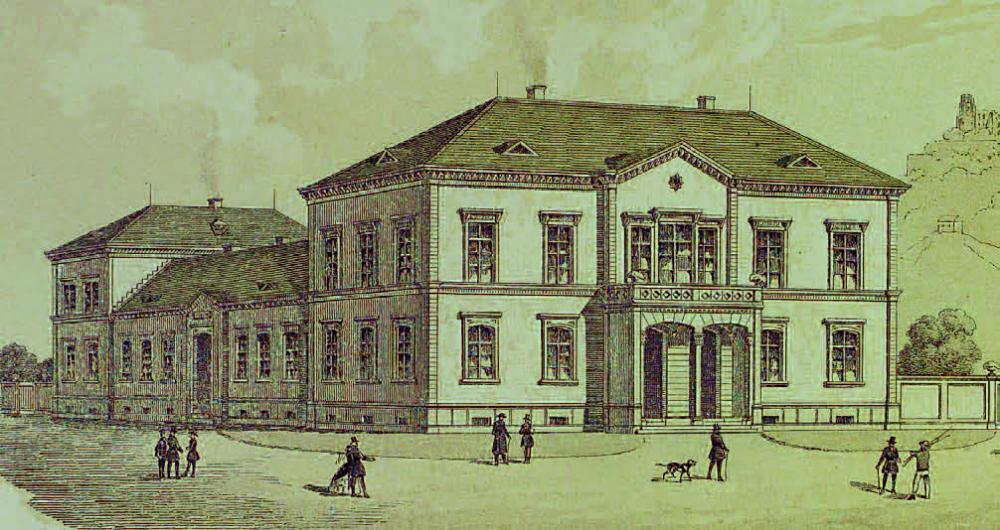

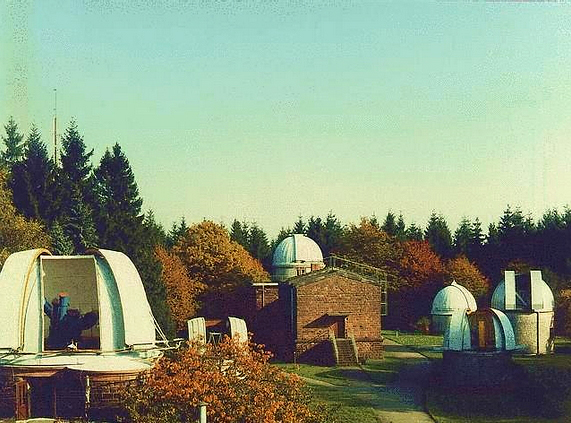

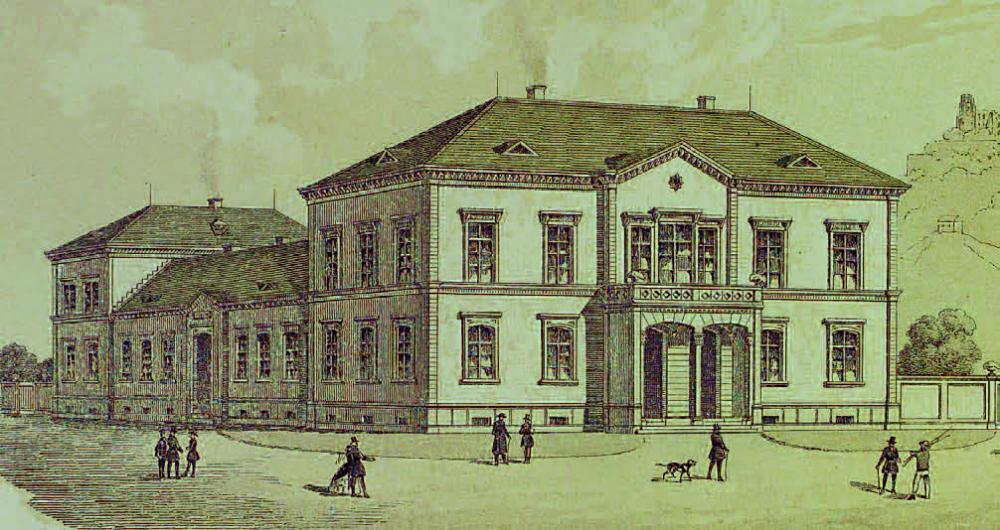

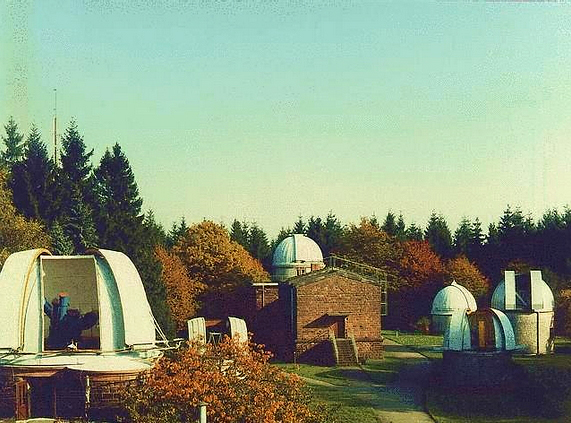

Fig. 3. Heidelberg Observatory (LSW, Uni HD)

Fig.: Heidelberg Observatory (LSW, Uni HD)

Thanks to the activity of Grand Duke Friedrich I of Baden (1826--1907), the Heidelberg State Observatory (Großherzogliche Bergsternwarte, later: Landessternwarte Heidelberg) was built on the Königstuhl (elevation 566m). On June 20, 1898, the Grand Ducal Mountain Observatory on the Königstuhl was inaugurated in the presence of the Grand Duke Friedrich I of Baden. Heidelberg was one of the first mountain observatories in Europe after Nice Observatory and comparable to the American mountain observatories like Lick.

First light on the Königsstuhl was on June 28, 1898.

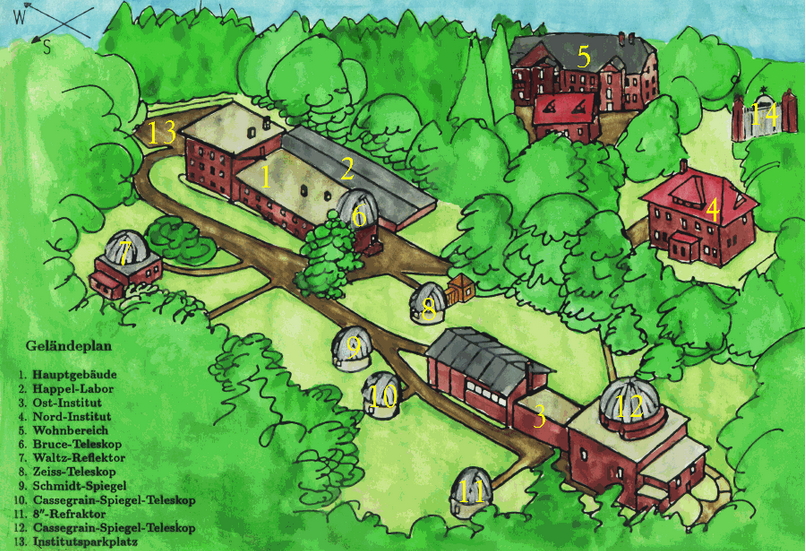

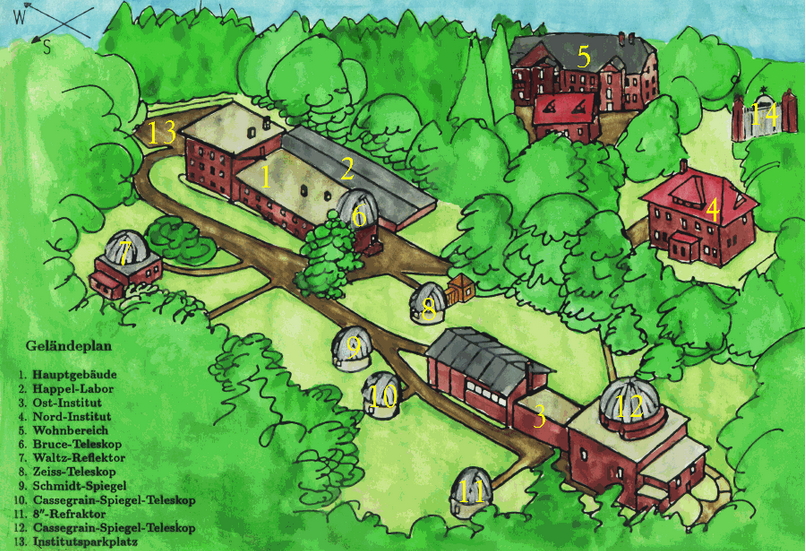

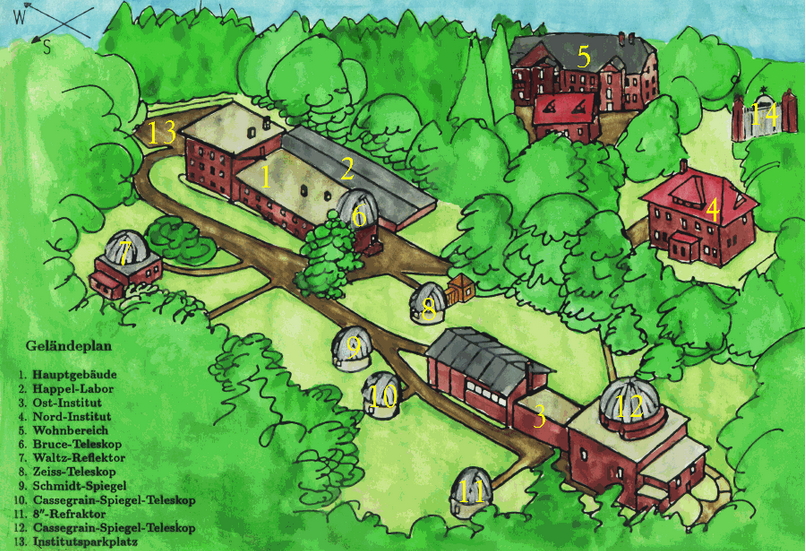

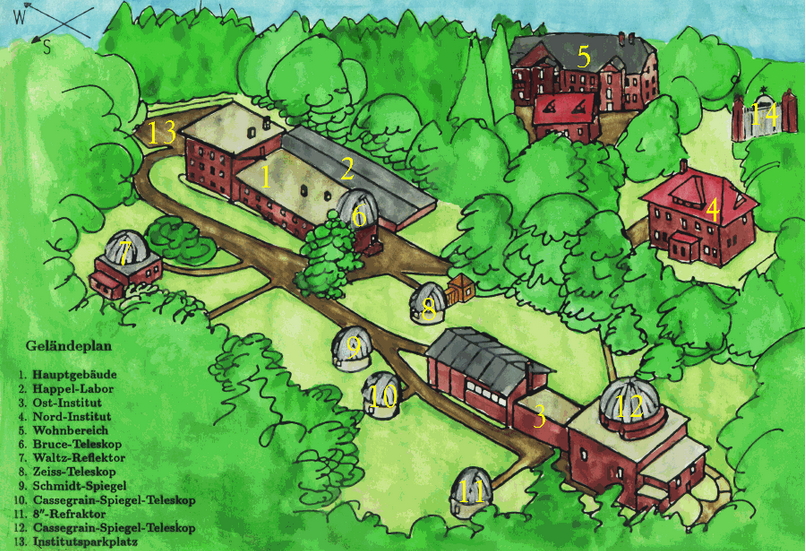

Fig. 4. Map of Heidelberg Observatory (LSW, Uni HD)

There were two scientific departments: The Astrometric Institute with the meridian instruments and slits (East Institute), headed by Karl Valentiner (1845--1931) and the Astrophysical Institute (West Institute) under Max Wolf. After Valentin’s retirement (1909), Max Wolf headed the entire institute.

The original instrumentation of Heidelberg Observatory came from Mannheim Observatory, founded in 1774, which had been relocated to Karlsruhe in 1880 due to the increasing deterioration of observation conditions.

Fig. 5. Entrance gate of Heidelberg Observatory (© Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

With the main instruments, the Bruce astrograph (August 16, 1900) and the Waltz reflector (1906) -- both financed by private foundations -- the institute was one of the most modern research facilities in the world at the time.

Max Wolf (1863--1932)

Fig. 6. Max Wolf (1863--1932), (Wikipedia)

Maximilian Franz Joseph Cornelius Wolf (1863--1932) studied physics as scholar of Georg Hermann Quincke (1834--1924) in Heidelberg, astronomy in Strasbourg, and did his doctorate in Heidelberg under the mathematician Leo Königsberger (1837--1921). Max Wolf initiated astrophysics in Heidelberg at the end of the 19th century, especiallly as a pioneer of photography. While still a student, he discovered in his private observatory the periodic comet 14P/Wolf, named after him.

Since 1893 Wolf was an associate professor at Heidelberg University. He turned down appointments to Göttingen and Vienna university Observatories. The astronomical institute initially consisted of two competing departments, the astrophysical under Max Wolf and the astrometric under Wilhelm Valentiner (1845--1931), who was first director in Mannheim and from 1880 to 1909 director of Karlsruhe Observatory. But after Valentin’s retirement in 1909, the departments were merged under the direction of Max Wolf until 1932.

Fig. 7a. North America Nebula NGC 7000 in the constellation Cygnus (1891), 13 hours exposure time (Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Wolf 1925, 0035)

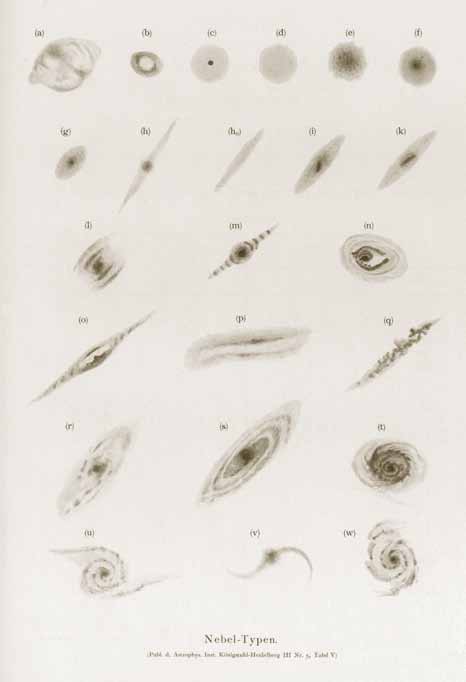

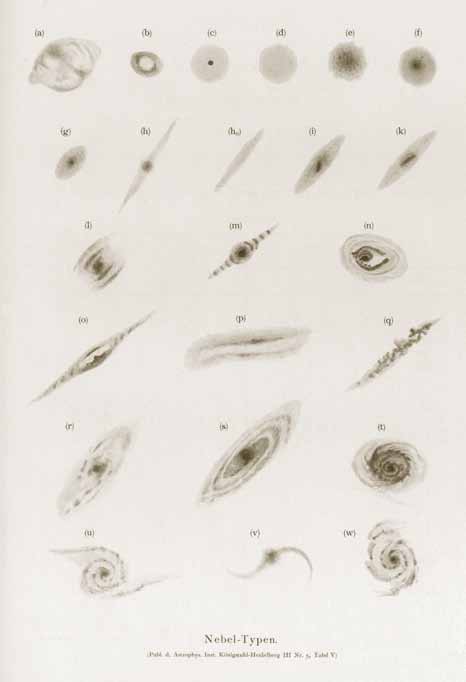

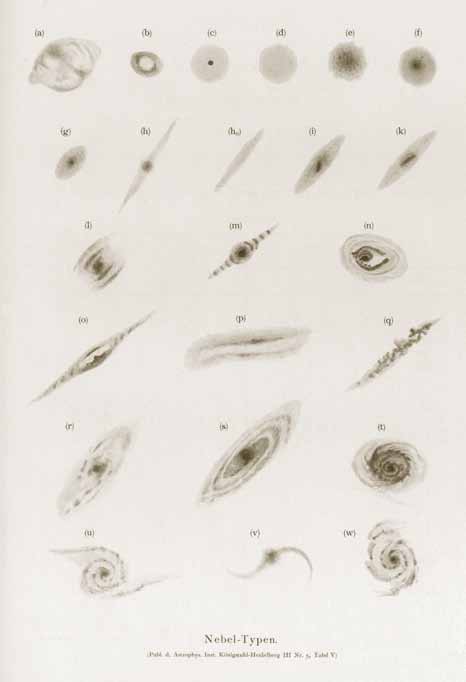

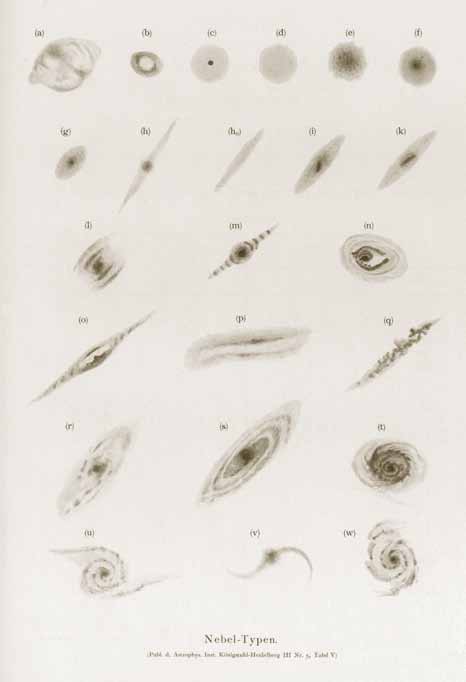

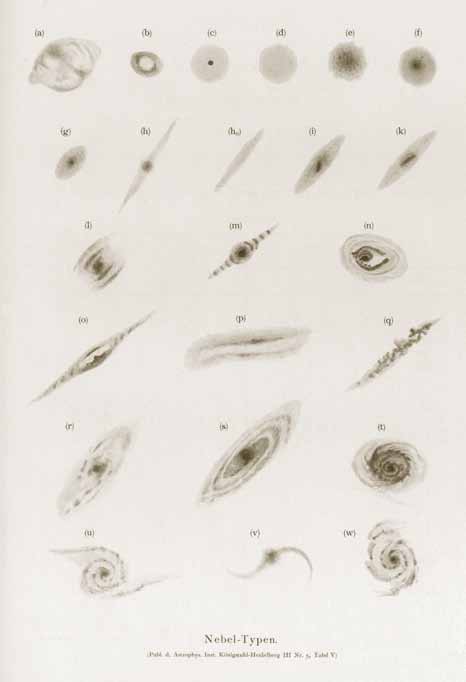

Fig. 7b. Types of nebulae, defined by Max Wolf in 1908 (LSW Heidelberg)

The celestial photography developed by Max Wolf made epochal discoveries possible, such as that of the North America Nebula in the constellation Cygnus (1891), the rediscovery of Halley’s Comet (1909), numerous variable stars are found, studies of the tail structure and spectra brought new knowledge about comets, followed by studies of the structure of the Milky Way system. Large nebulae in the constellations Orion, Cygnus and Auriga are discovered on photographic plates. Spectra reveal that "nebulae" are gas structures like Huggins had already proposed in 1864. For his remarkable photographic recordings, Wolf was awarded with gold medals at the world exhibitions in Paris (1900) and St. Louis (1904).

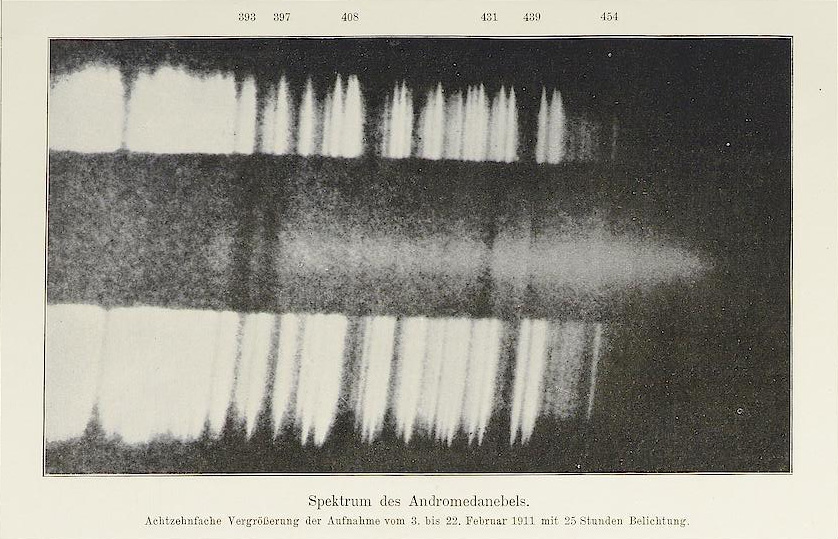

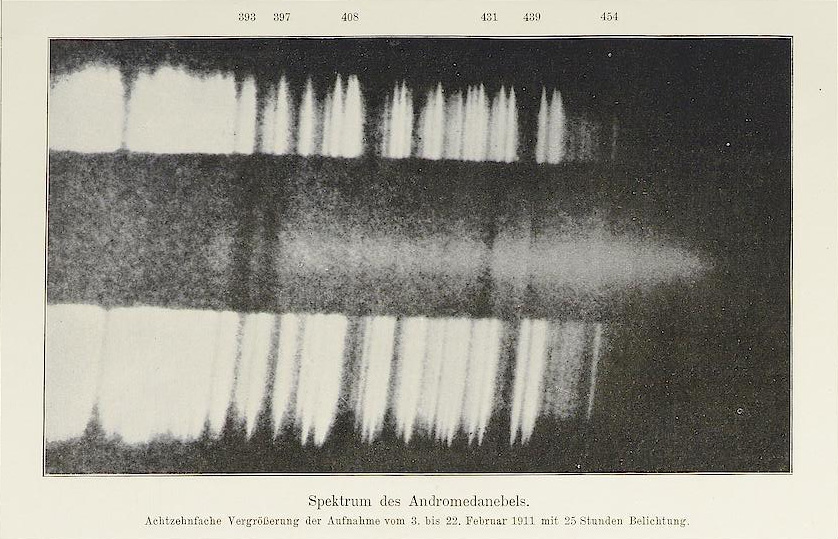

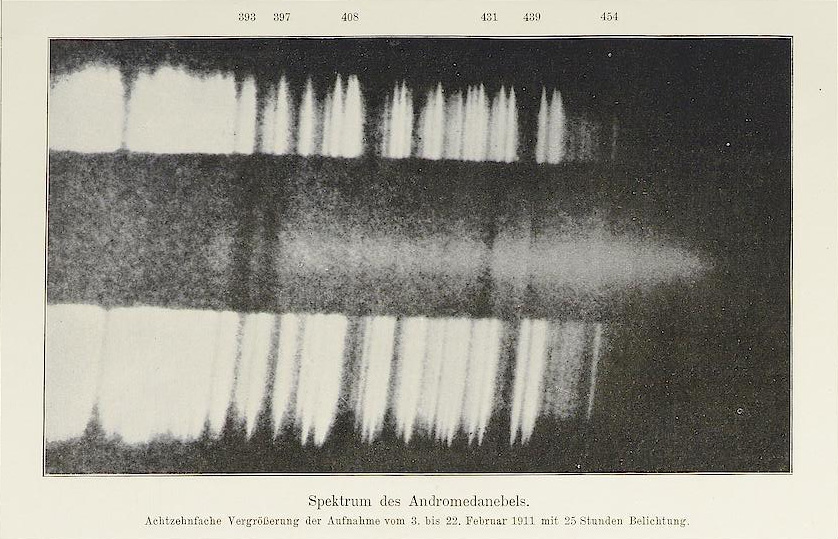

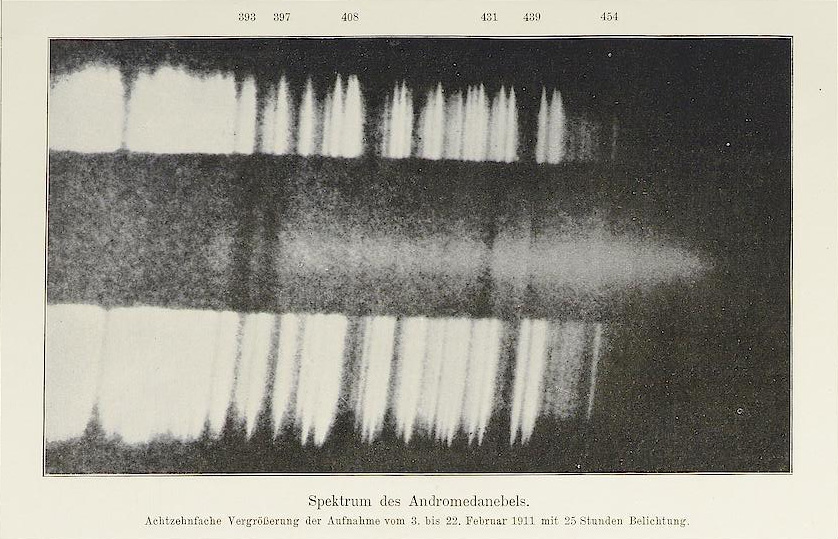

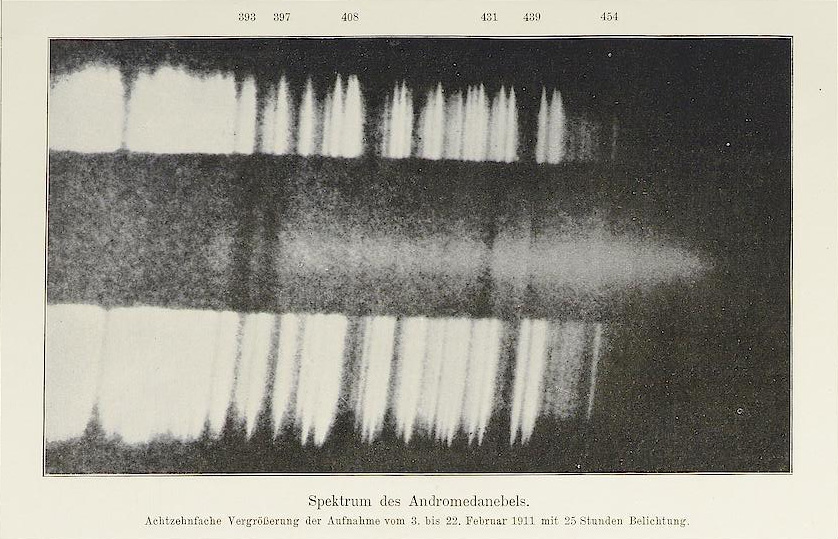

Fig. 8. Max Wolf’s Spectrum of the Andromeda nebula (1911), 25 hours exposure time (Sitzungsberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften, Math.-Naturwiss. Klasse, Abt. A, 1912)

In spiral nebulae like Andromeda, recognized by Julius Scheiner (1858-1913) as stellar system outside of our Milky Way, the systematic shift in the spectral lines was recognized by Max Wolf (1913). Wolf developed the blink comparator together with Carl Pulfrich (1858--1927) from the Zeiss company. By quickly comparing two photo plates, changes in positions are obvious and thus comets and asteroids could be discovered, in addition, variable stars could be recognized due to the blinking effect. Wolf discovered ten novae in this way.

Fig. 9a. Blink comparator, Carl Zeiss of Jena (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 9b. Comet Morehouse (1908), Stereoscopic images (1913) (LSW Heidelberg)

Fig. 9c. Asteroid (323) Brucia, the first asteroid, discovered by Max Wolf using the photographic method in 1891, model, Haus der Astronomie (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Up until the 1950s, the emphasis of Max Wolf’s research was concentrated on asteroids: around 800 were discovered on photographic plates in the Königstuhl Observatory by Max Wolf and his cooperators, including the first Jupiter Trojan Asteroid 588 Achilles in 1906.

The asteroid (323) Brucia, discovered by Max Wolf on December 22, 1891, was the first asteroid using the photographic method, and the lunar crater Bruce were named in memory of the donation of the Bruce Reflector by Catherine Wolfe Bruce (1816--1900).

Fig. 10. Catherine Wolfe Bruce (1816--1900), (Wikipedia)

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 10

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-15 18:37:22

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

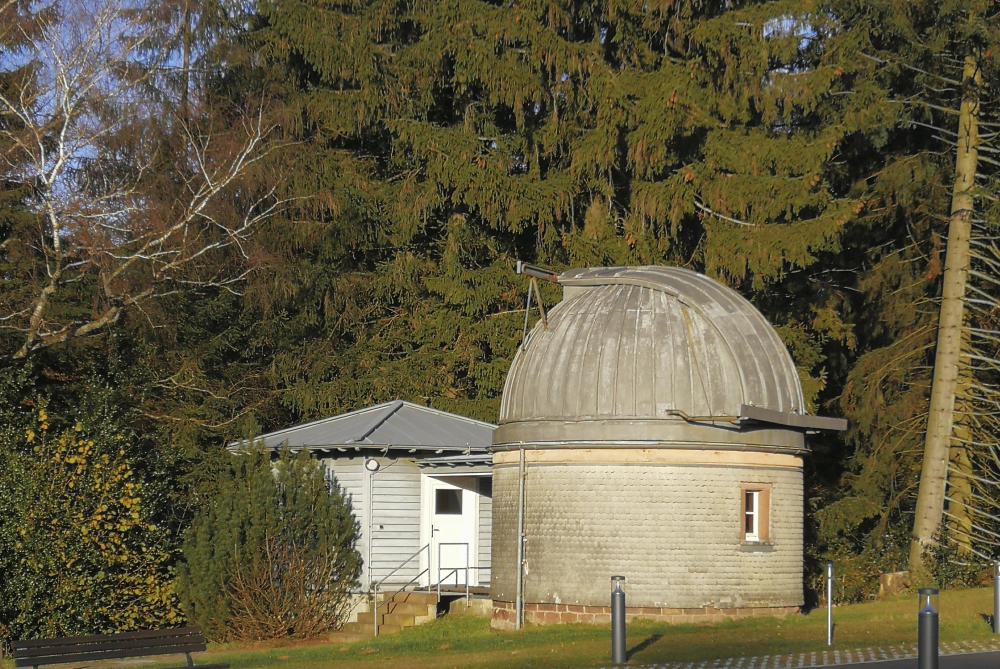

Fig. 11. Six domes of Heidelberg Observatory (Wikipedia, CC3, Mhdman)

In 1898, the "Großherzogliche Bergsternwarte" (Grand Ducal Mountain Observatory) was inaugurated by Grand Duke Friedrich I of Baden.

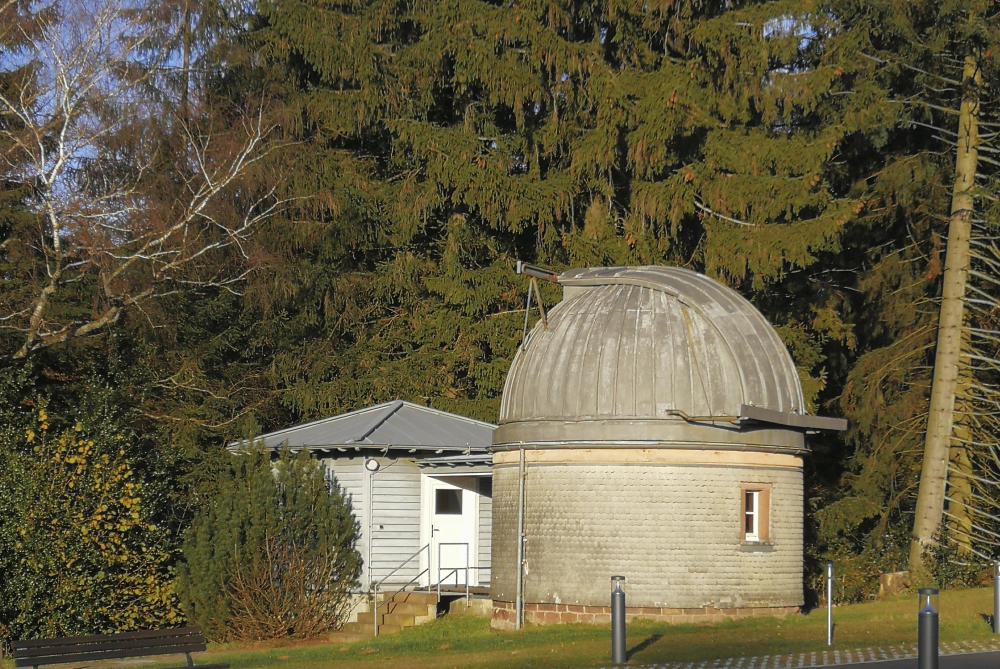

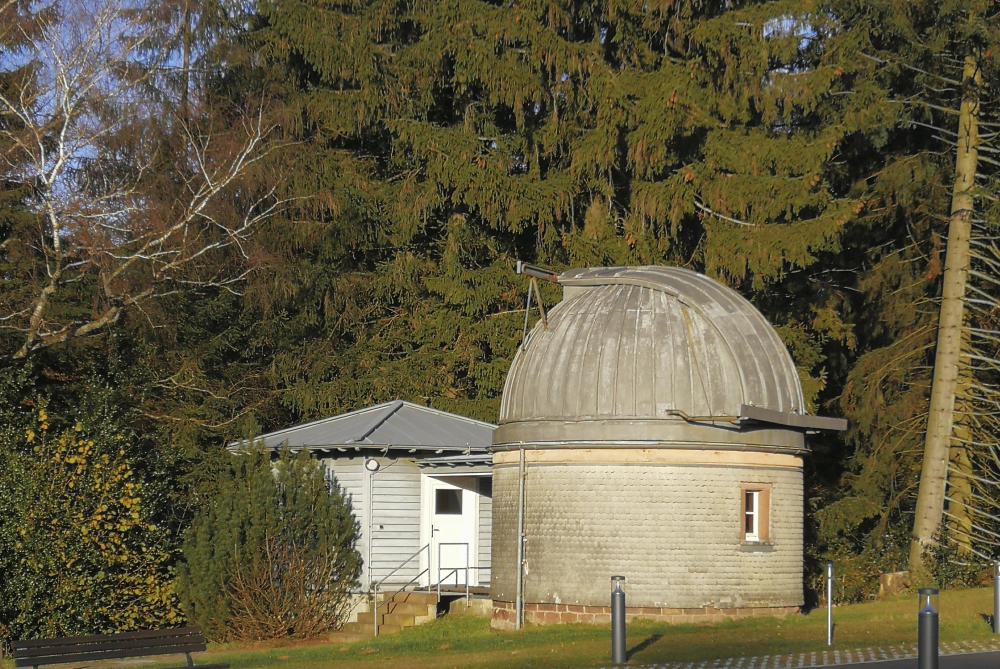

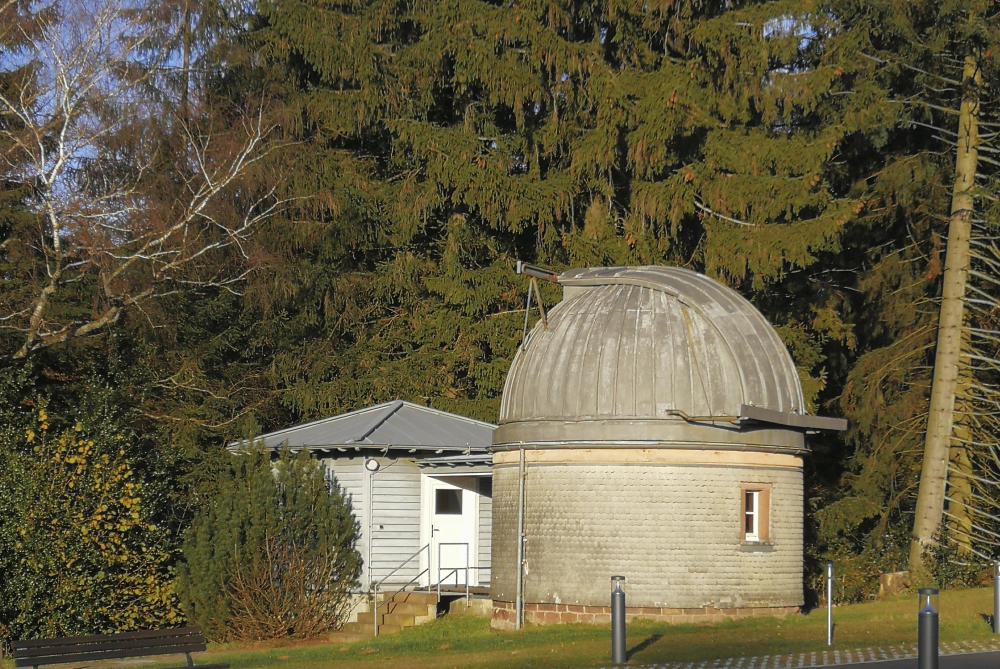

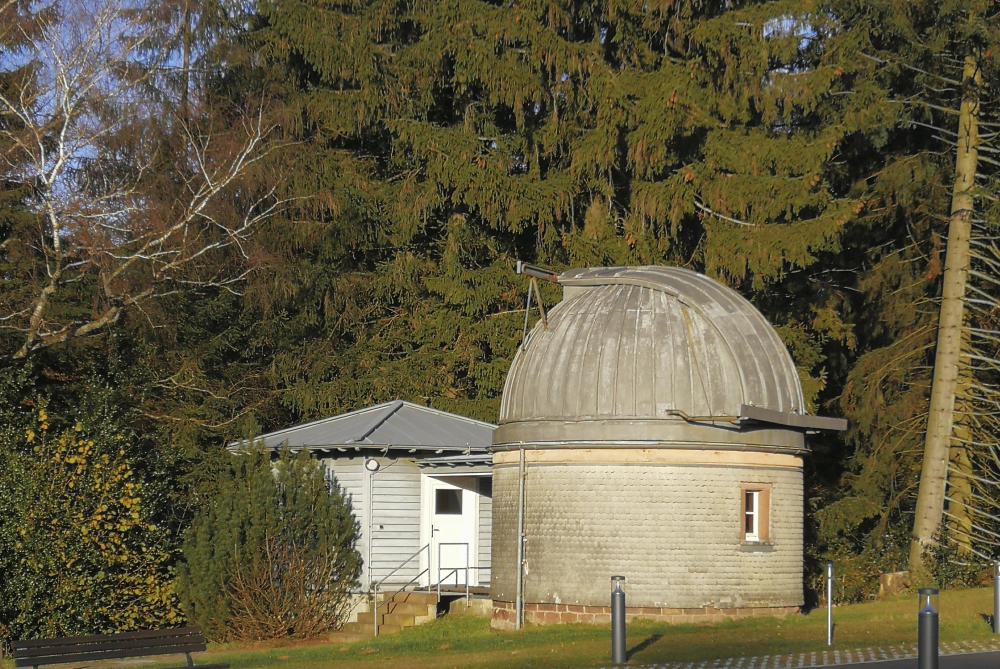

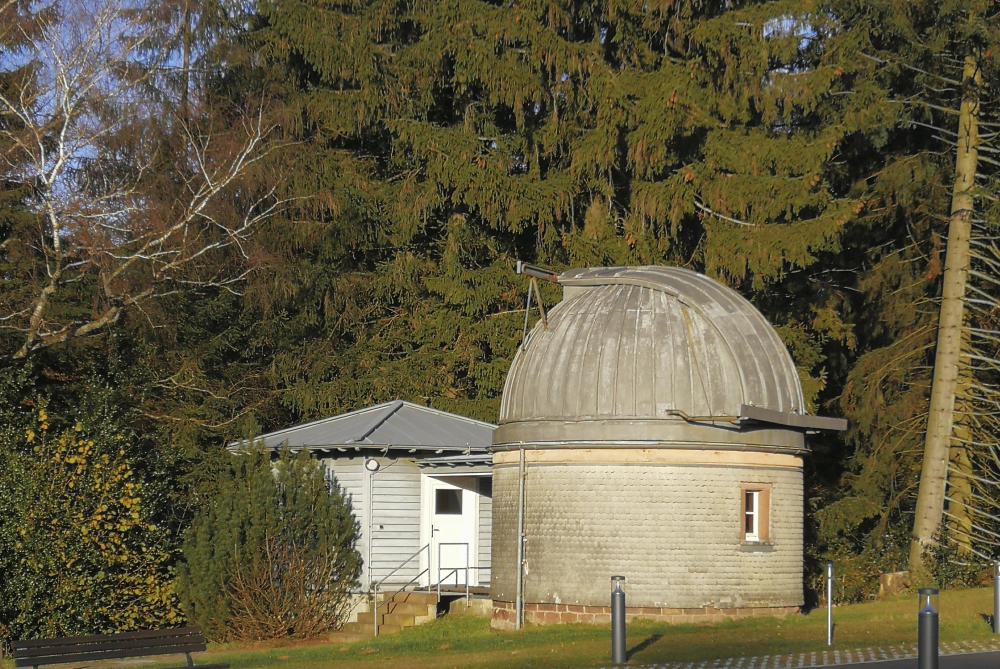

Fig. 12a. Kann Refractor Building (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12b. 8-inch-Kann Refractor, Merz of Munich (Photo: Werner Zigs)

Fig. 12c. Bruce-Telescope Dome (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12d. 40-cm-Bruce photographic double refractor (1900), 1900 -- donated by Catherine Wolfe Bruce (1816--1900) of New York (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12e. 40-cm-Bruce double astrograph (1900), 1900 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12f. 40-cm-Bruce double astrograph (1900), 1900 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12g. Zeiss-Telescope Building (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12h. Waltz-Telescope Building - just in restoration (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

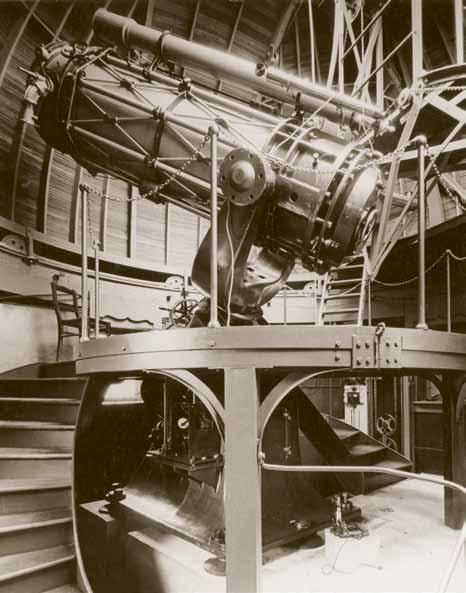

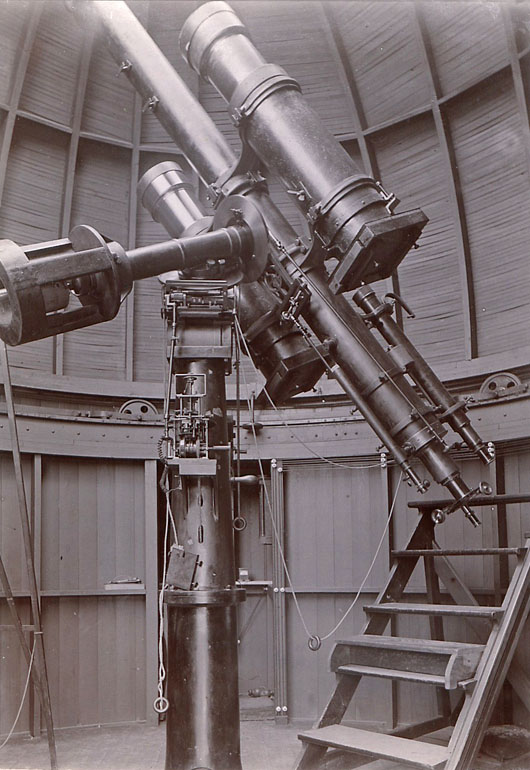

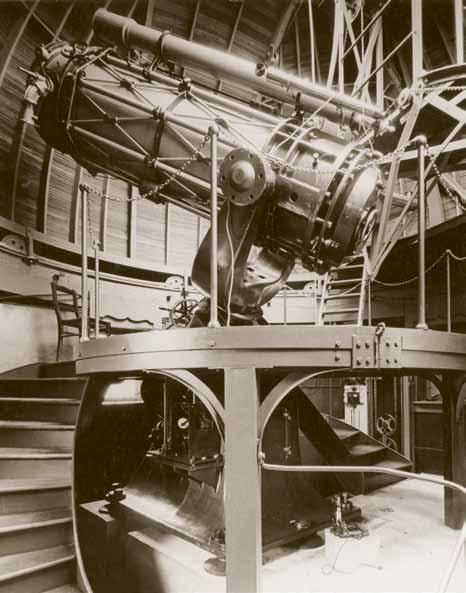

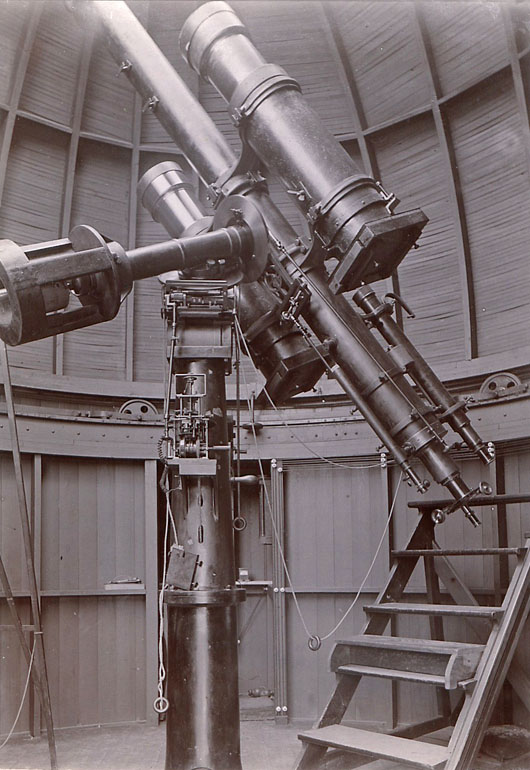

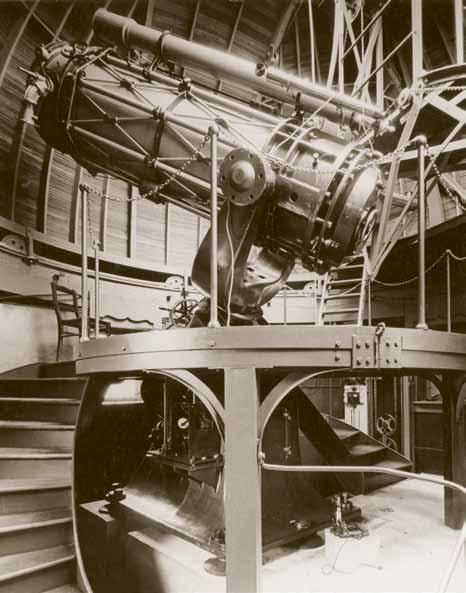

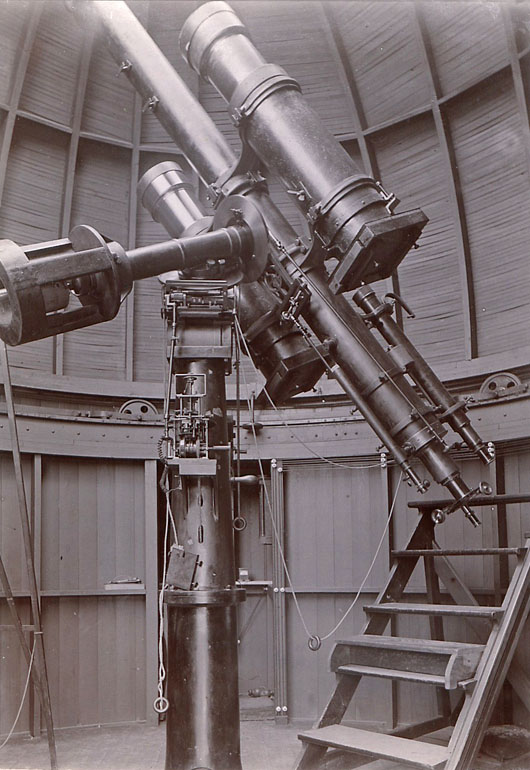

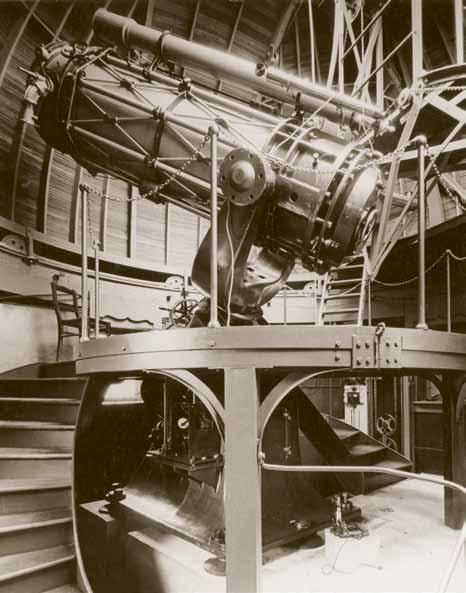

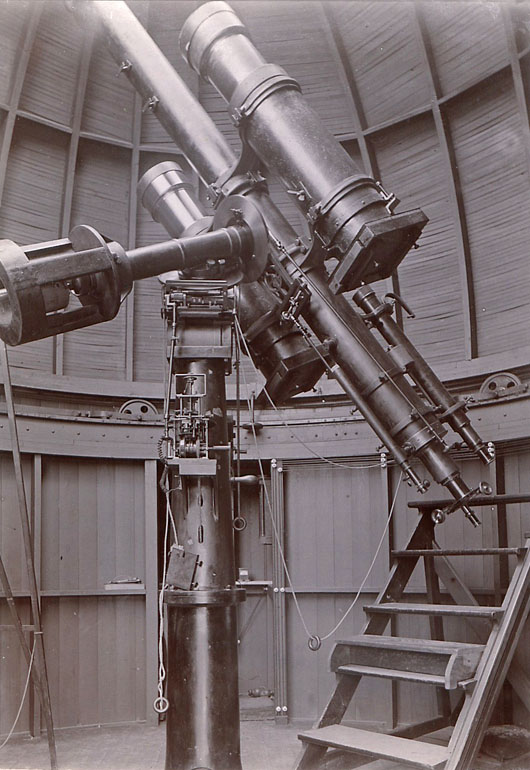

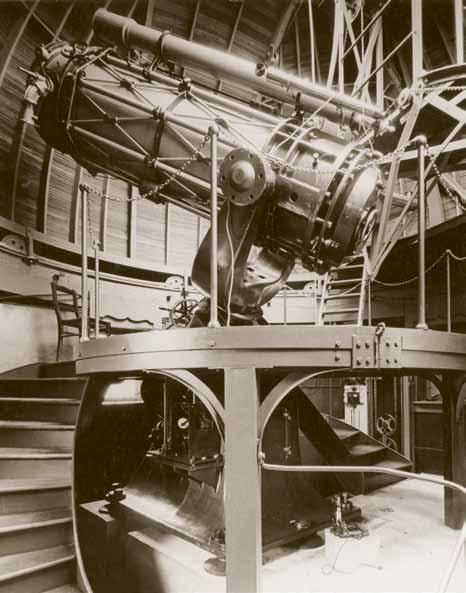

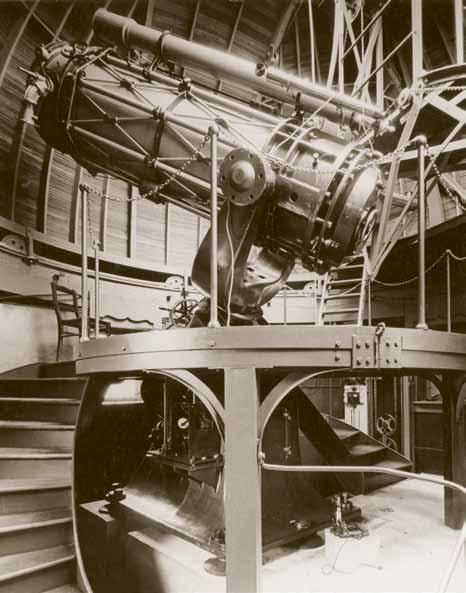

Fig. 12i. 72cm-Waltz-Telescope (Newton), Nasmyth-Focus, Carl Zeiss of Jena (1906) (LSW Heidelberg)

Instruments

- 6-inch-Refractor (1859), used for the visual observation of double stars, later was used until 1924 to measure star clusters like globular clusters, and then for teaching and training purposes; in 1957, the 6-inch-Refractor was donated to the public observatory in Karlsruhe.

- Max Wolf’s instrument from his private observatory: 6-inch-Double Astrograph, consisting of two portrait cameras, made by Voigtländer of Braunschweig (1892 and 1893), and a guiding telescope, Reinfelder & Hertel of Munich, on a German mounting, made by "M. Sendtner of Munich" in a 5-m-dome; he added also smaller objectives like 5-inch-Kranz and 61-mm-Steinheil. The 6-inch-astrograph was used on Königsstuhl from 1898 until 1960, first in a white dome, then since 1919 in a black dome. The last photographic plate was exposed on June 16, 1939, for 4 minutes, it showed the variable star P Cygni.

- 8-inch-Kann Refractor (20-cm diameter, 300-cm focal length), wooden tube, German mounting, Merz, Munich -- the oldest telescope of the Landessternwarte, already mentioned in the annual report of 1894 of the Karlsruhe Observatory, donated by L. Kann.

- 40-cm-Bruce-Telescope (16-inch, focal length 2m), a photographic double refractor (astro camera), diameter of the photographic lenses 40-cm, visual guiding telescope (objective diameter 25-cm, focal length 4-m), first light August 1900 -- donated by Catherine Wolfe Bruce (1816--1900) of New York. Thousands of photographic plates were taken with this astrograph.

- 72cm-Waltz-Telescope (Newton), Nasmyth-Focus, Carl Zeiss of Jena (1906) with a two-prism-Spectrograph.

It was the first "large" reflector, made by Carl Zeiss of Jena; shortly afterwards, 1911, the Hamburg 1-m-Reflector was built.

- Schmidt telescope (main mirror diameter 40-cm, diameter of the correction plate 25-cm, focal length 90-cm (f:3.6), produced in the Heidelberg workshop (1963), large field of view (4°), used with objective lens prism

- 50-cm-Cassegrain Reflector, main mirror diameter 50-cm, focal length 6.95-m (f:14), produced in the Heidelberg workshop (1978), used for stellar photometry and polarimetry.

Until 1978, a 12-inch-refractor (4.22-m focal length), Steinheil, donated by Kreßmann, was used as guiding telescope.

- 75-cm Ritchey-Chretien-Cassegrain-Telescope (focal length 6-m, f:8), Carl Zeiss of Oberkochen (1977), used with CCD, used since 2005 in the ATOM-Project in Namibia

- 70-cm Cassegrain Reflecting telescope (focal length 5.6-m, f:8), (1988), used with CCD camera.

- Stereokomparator, Carl Zeiss of Jena

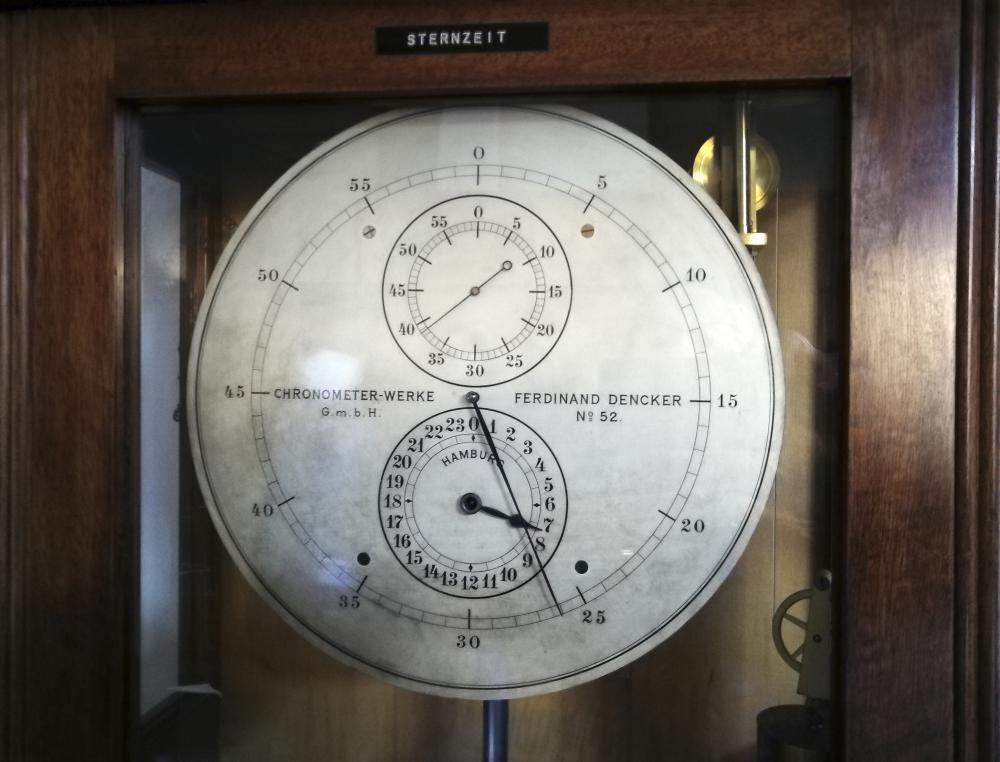

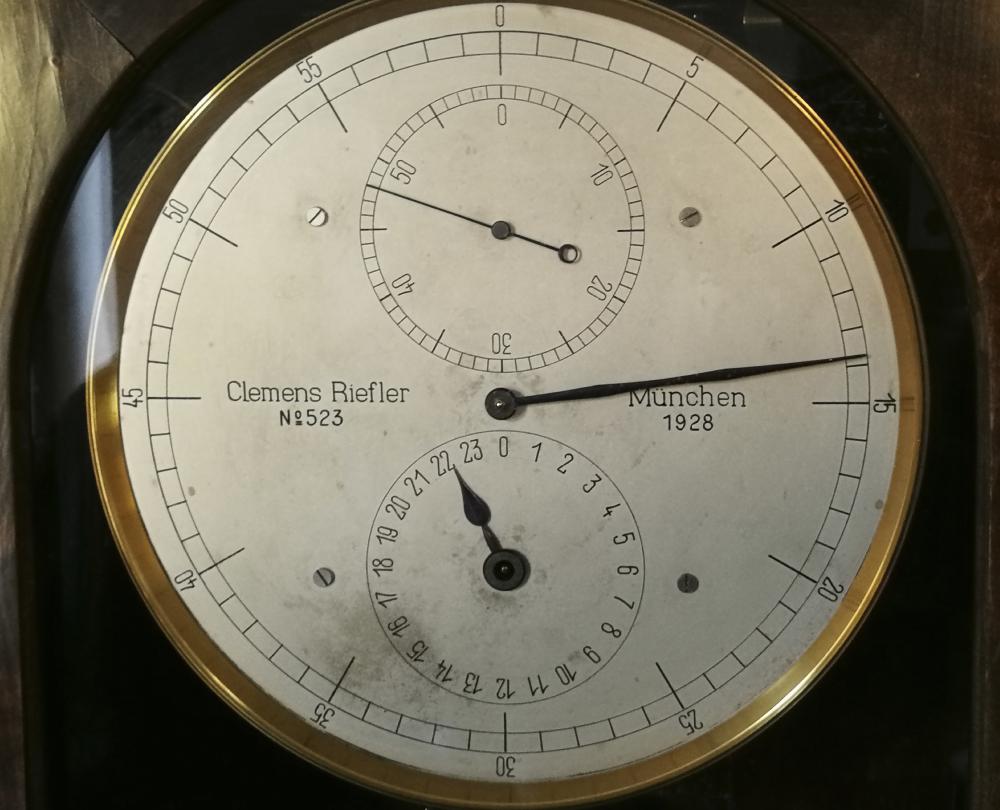

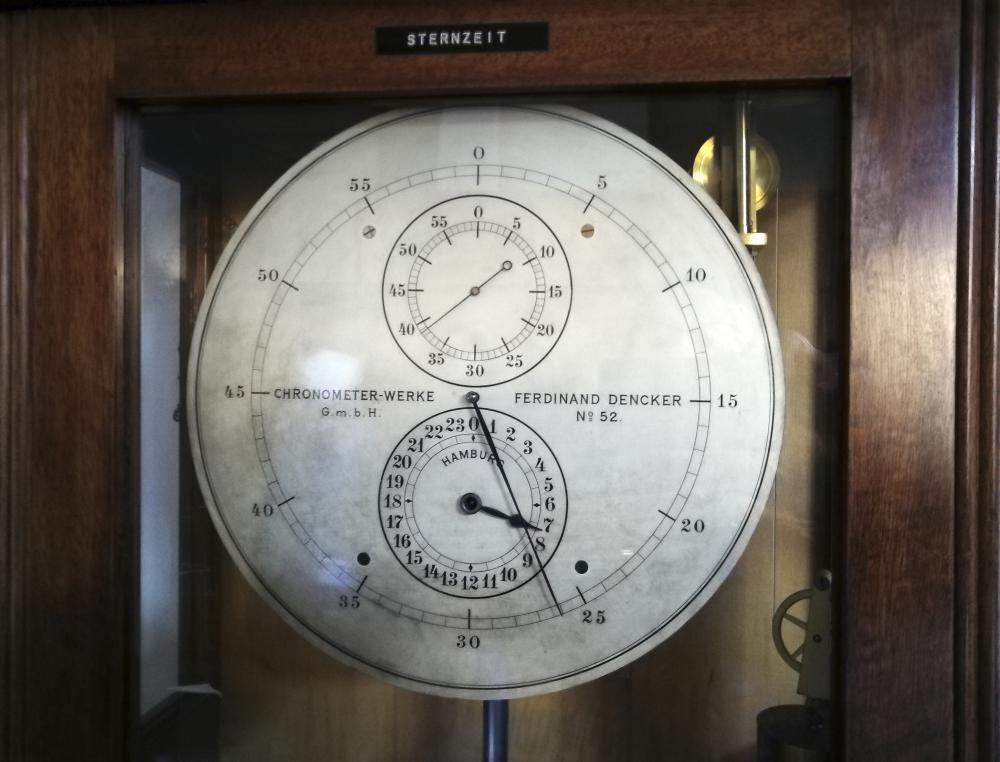

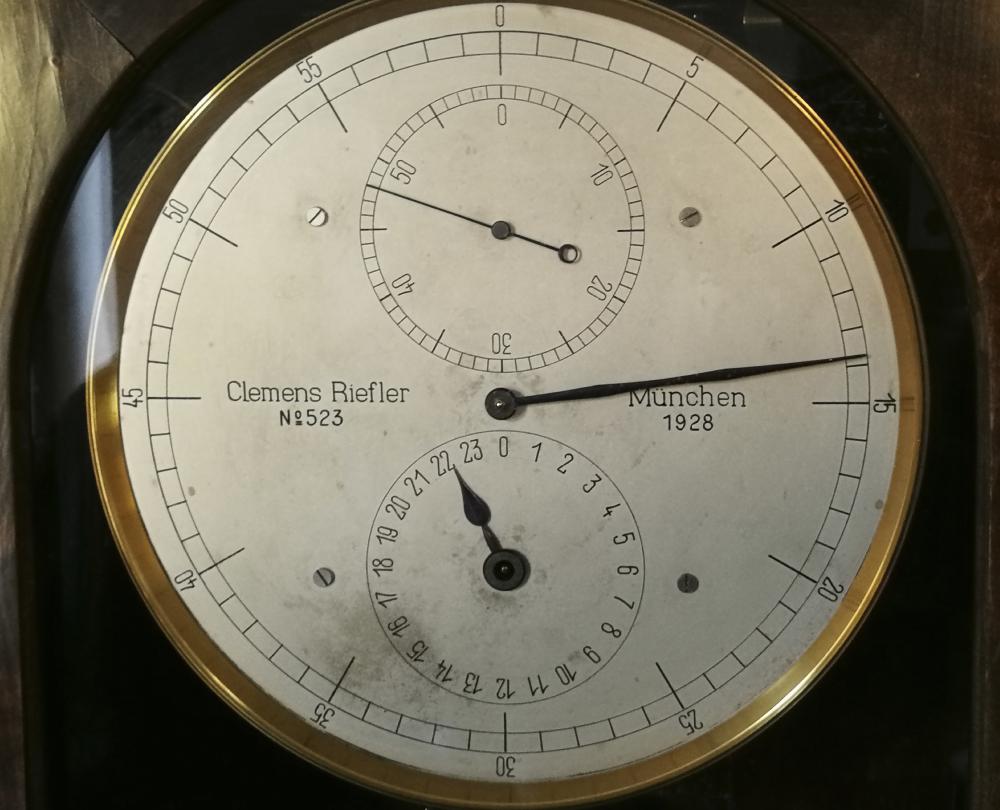

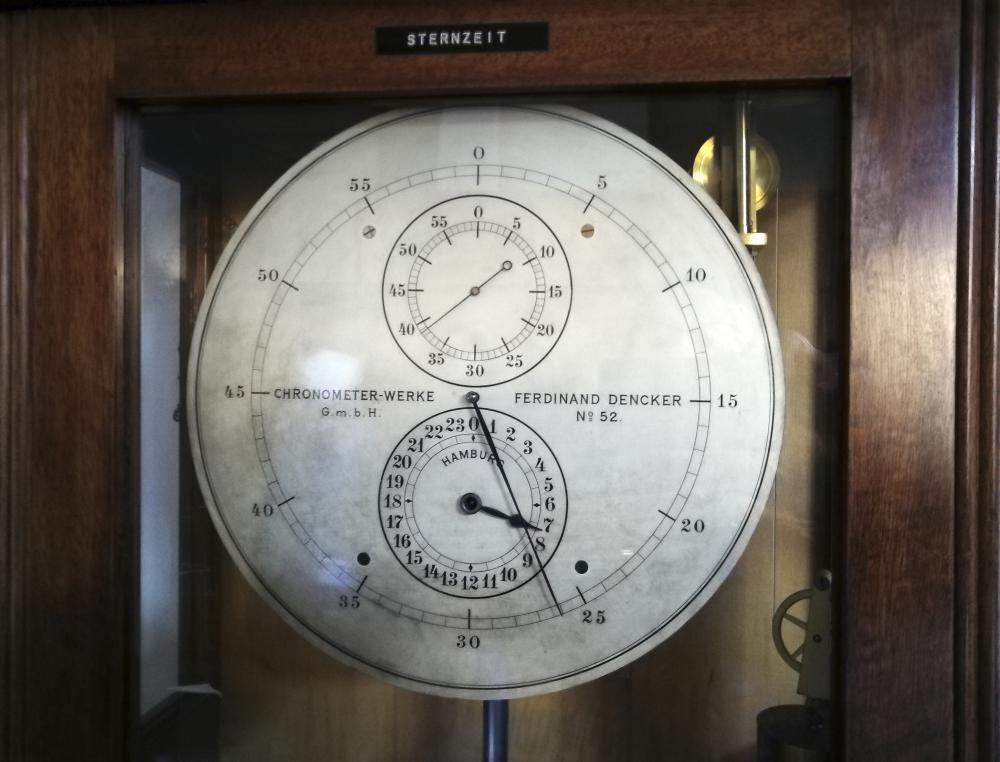

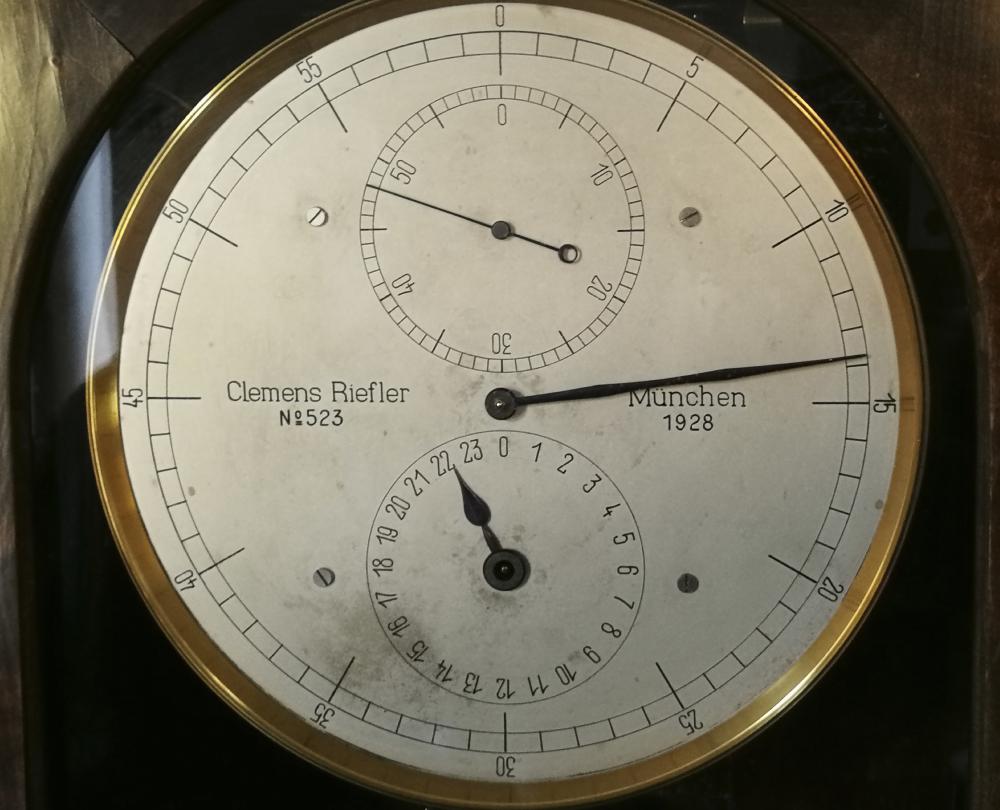

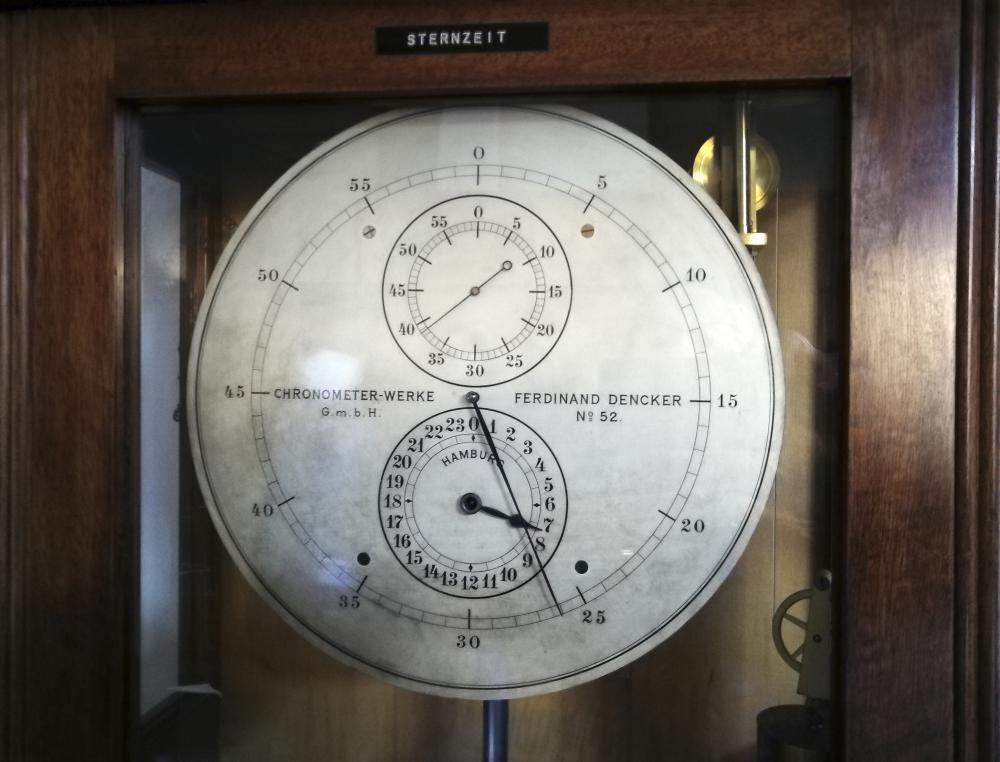

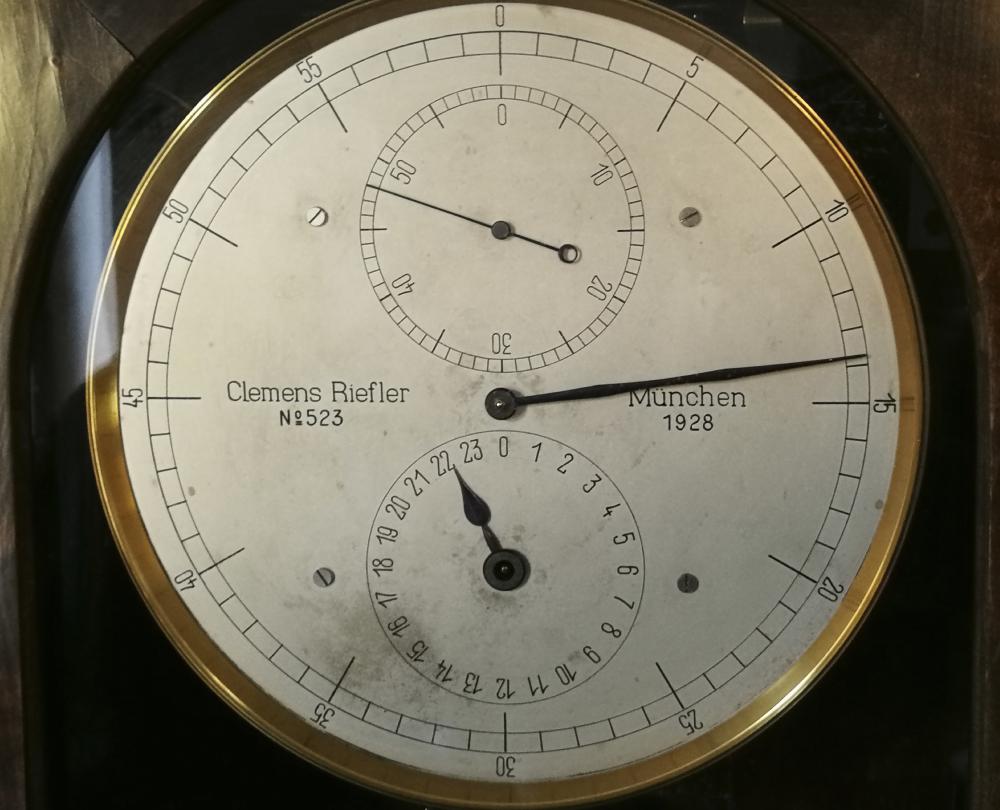

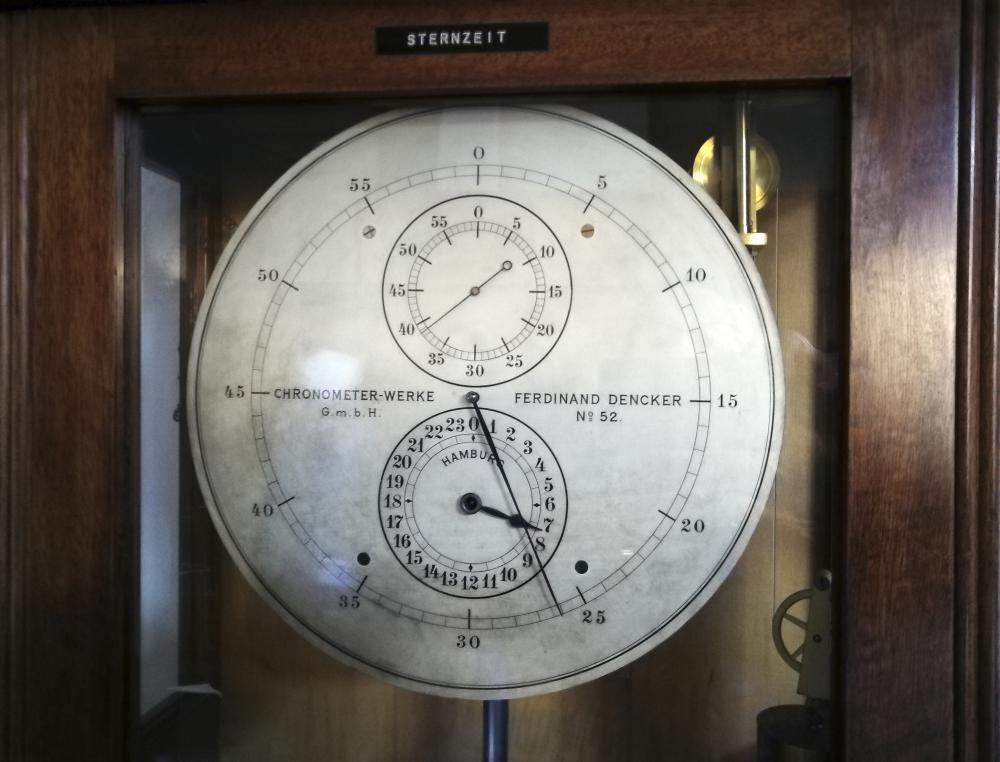

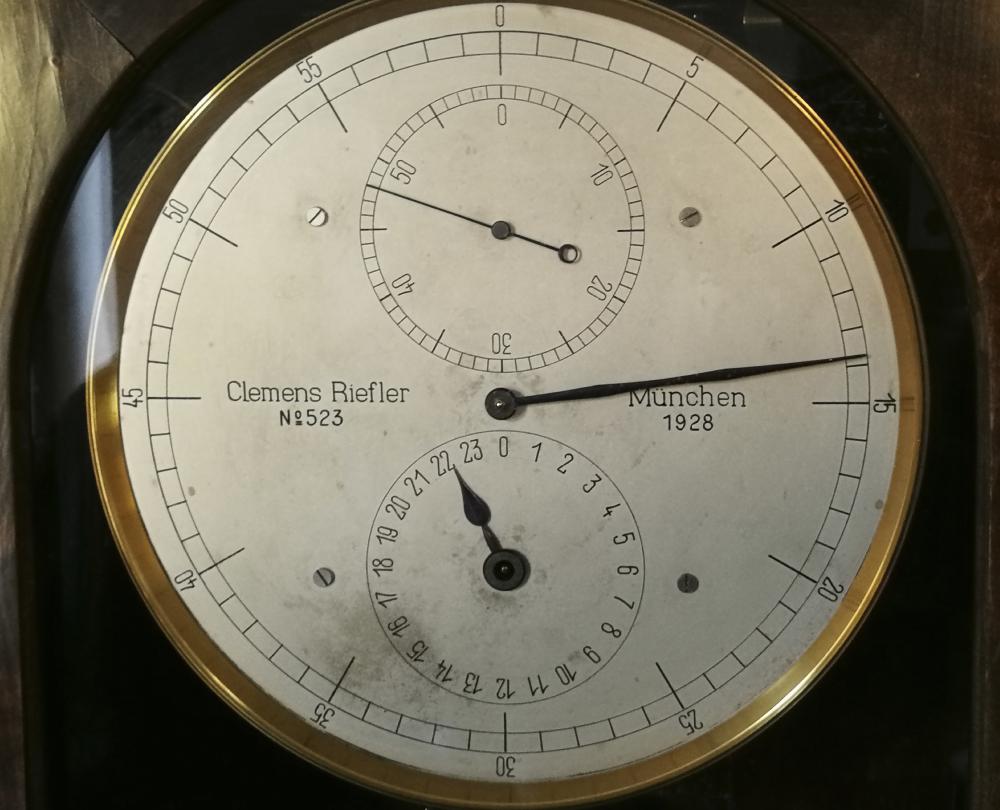

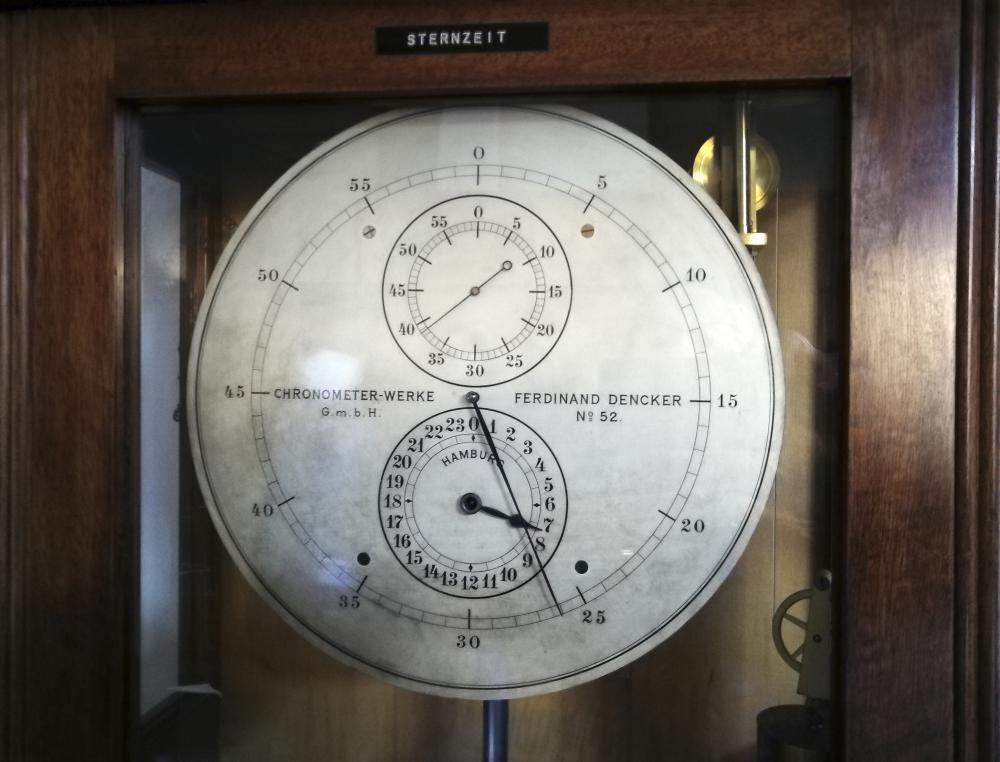

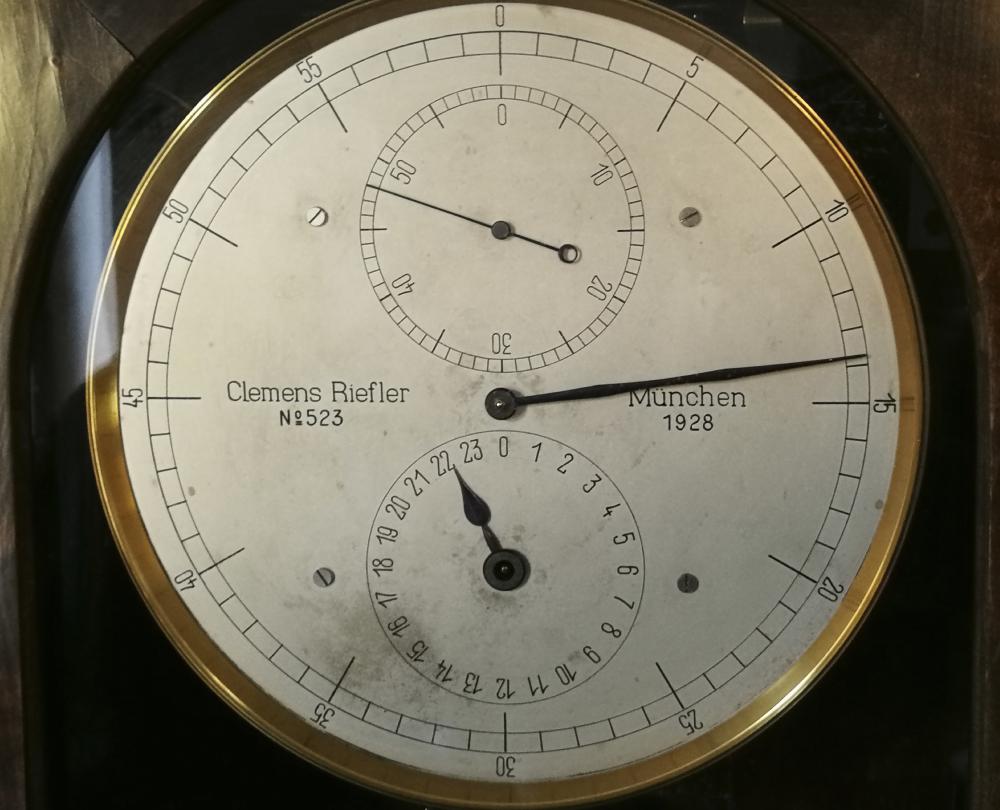

- Pendulum clocks: Chronometerwerke GmbH, Ferdinand Dencker, No. 52 (sidereal time), S. Riefler, No. 44, Munich (1899), Clemens Riefler, No. 523, Munich (1928)

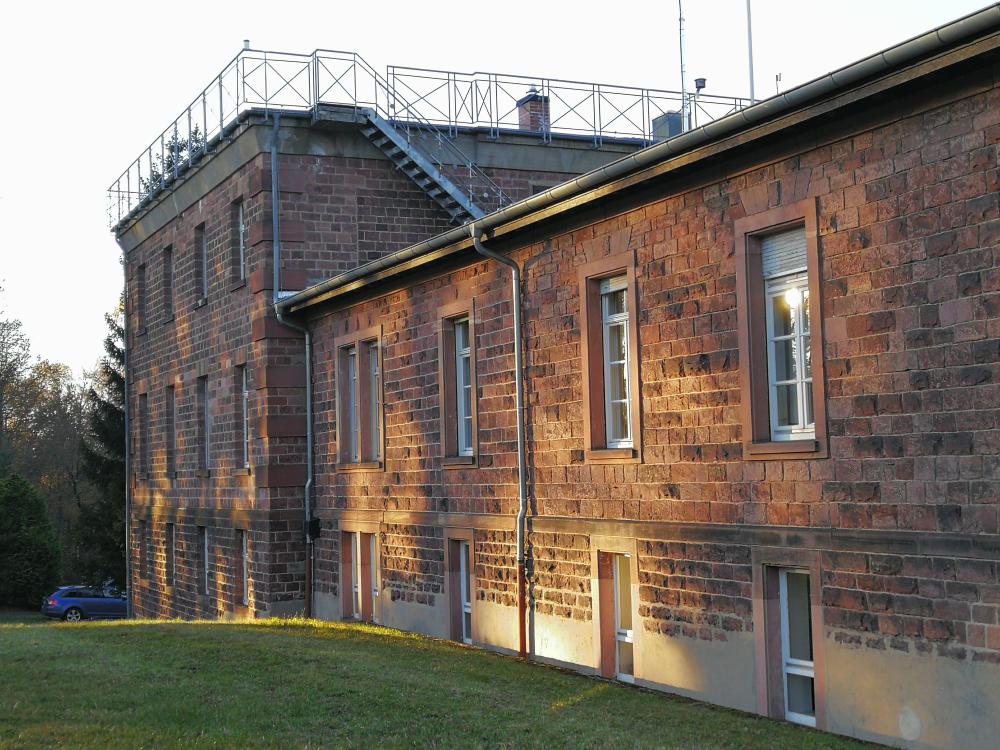

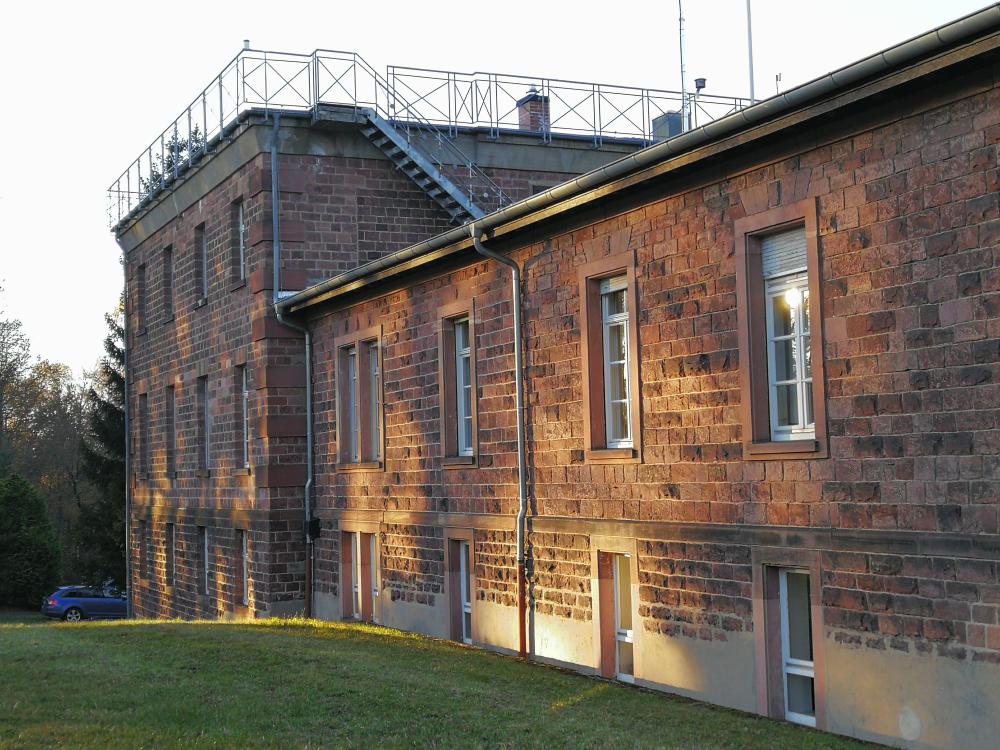

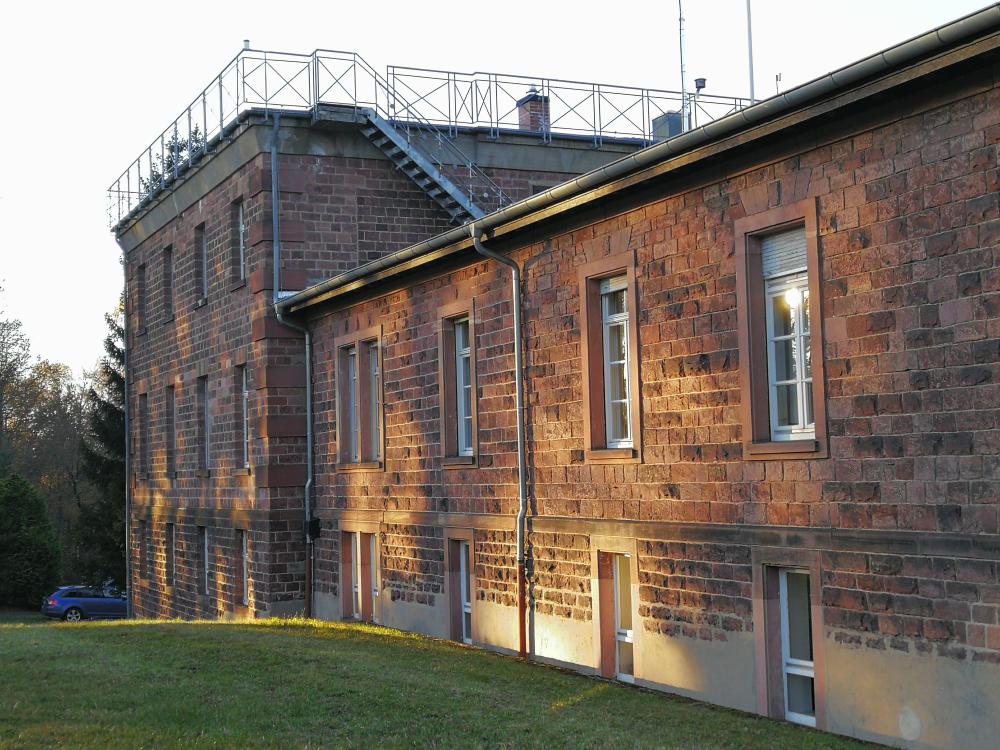

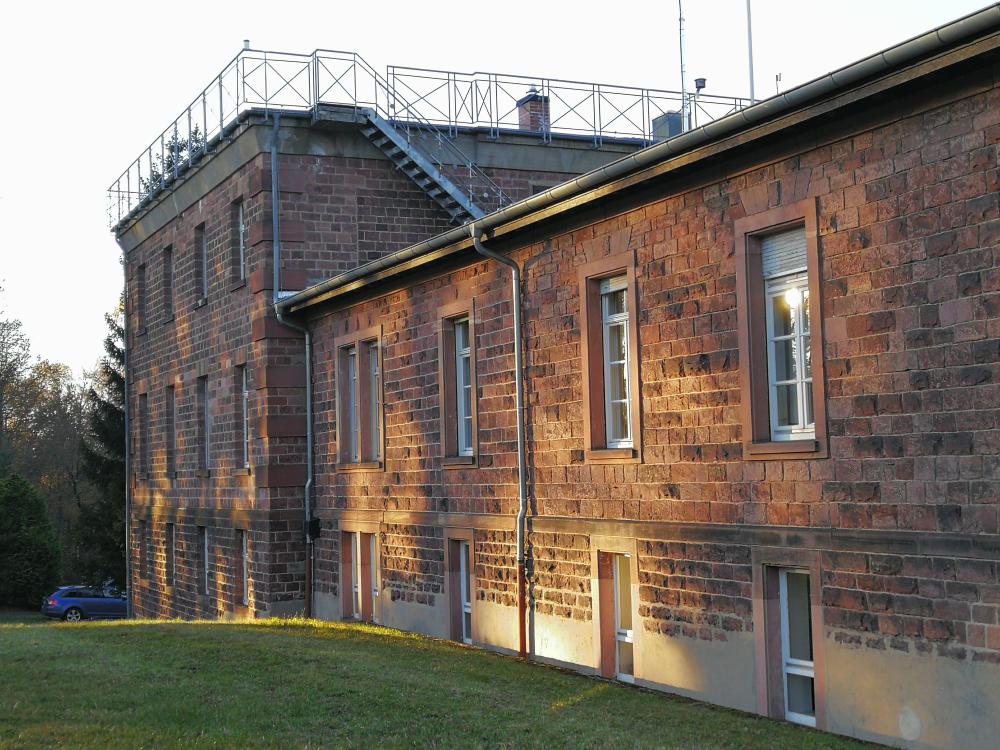

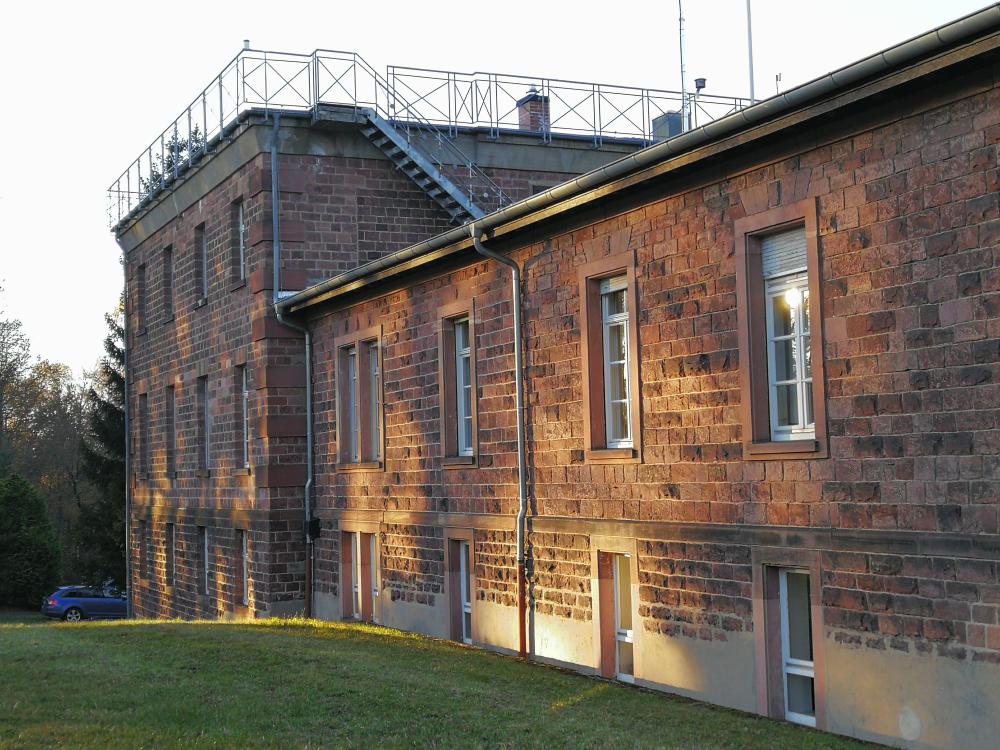

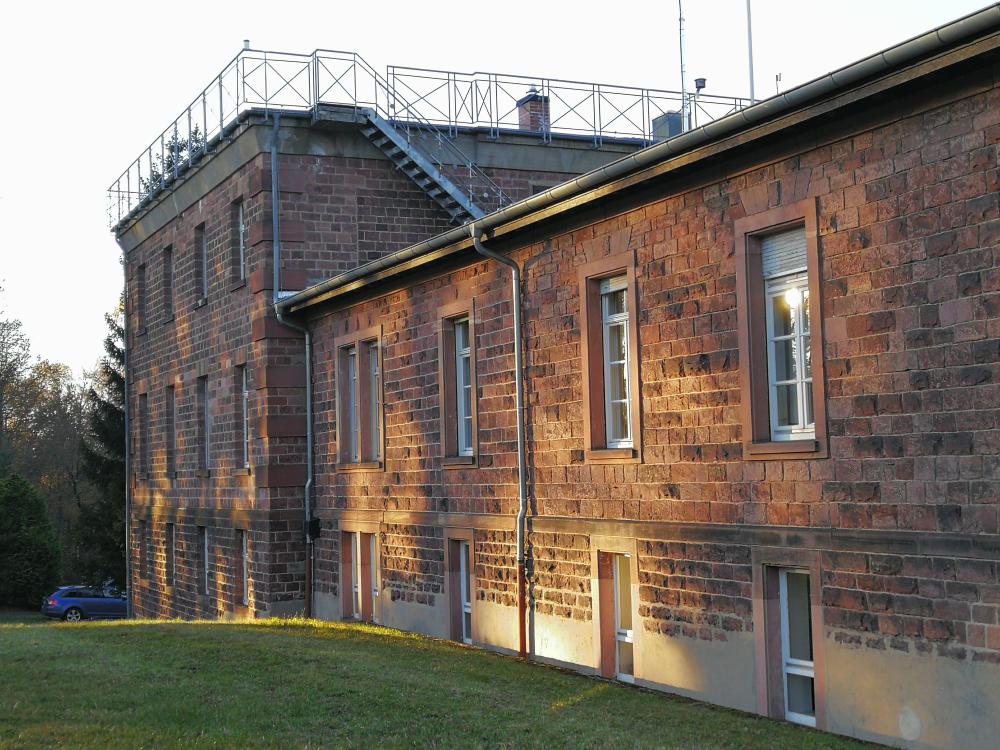

Fig. 13a. Main Building (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13b. Waltz Reflector building and memorial plaque Max Wolf (1953), (Photo: Dietrich Lemke)

Fig. 13c. Zeiss Telescope Building and Bruce Dome (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13d. East Institute and Schmidt Telescope dome and two Cassegrain domes (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13e. East Institute and Cassegrain dome (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13f. Pendulum clock Chronometerwerke GmbH, Ferdinand Dencker, No. 52 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13g. Pendulum clock S. Riefler, No. 44, Munich (1899), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13h. Pendulum clock Clemens Riefler, No. 523, Munich (1928), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

After Wolf’s death (1932), the theorical astronomer Heinrich Vogt (1890--1968) was entrusted with the management of the observatory. His research was in stellar structure (Vogt-Russell-Theorem). In 1931, he became a member of the NSDAP, and in 1933, he became a member of the SA (Obersturmführer). In 1933, he got the call as full professor at the University of Heidelberg.

August Kopff (1882--1960), a former student of Max Wolf and director of the Astronomical Computing Institute (Astronomisches Recheninstitut, ARI), 1924 to 1954 in Berlin, and since 1945 in Heidelberg, took over the management of Heidelberg Observatory. He discovered Kopff’s comet in 1906 (rendezvous of the Galileo space probe), and 66 asteroids in the period from 1905 to 1909. But he was already in the 1920s interested in the General Theory of Relativity, gave lectures and published a textbooks.

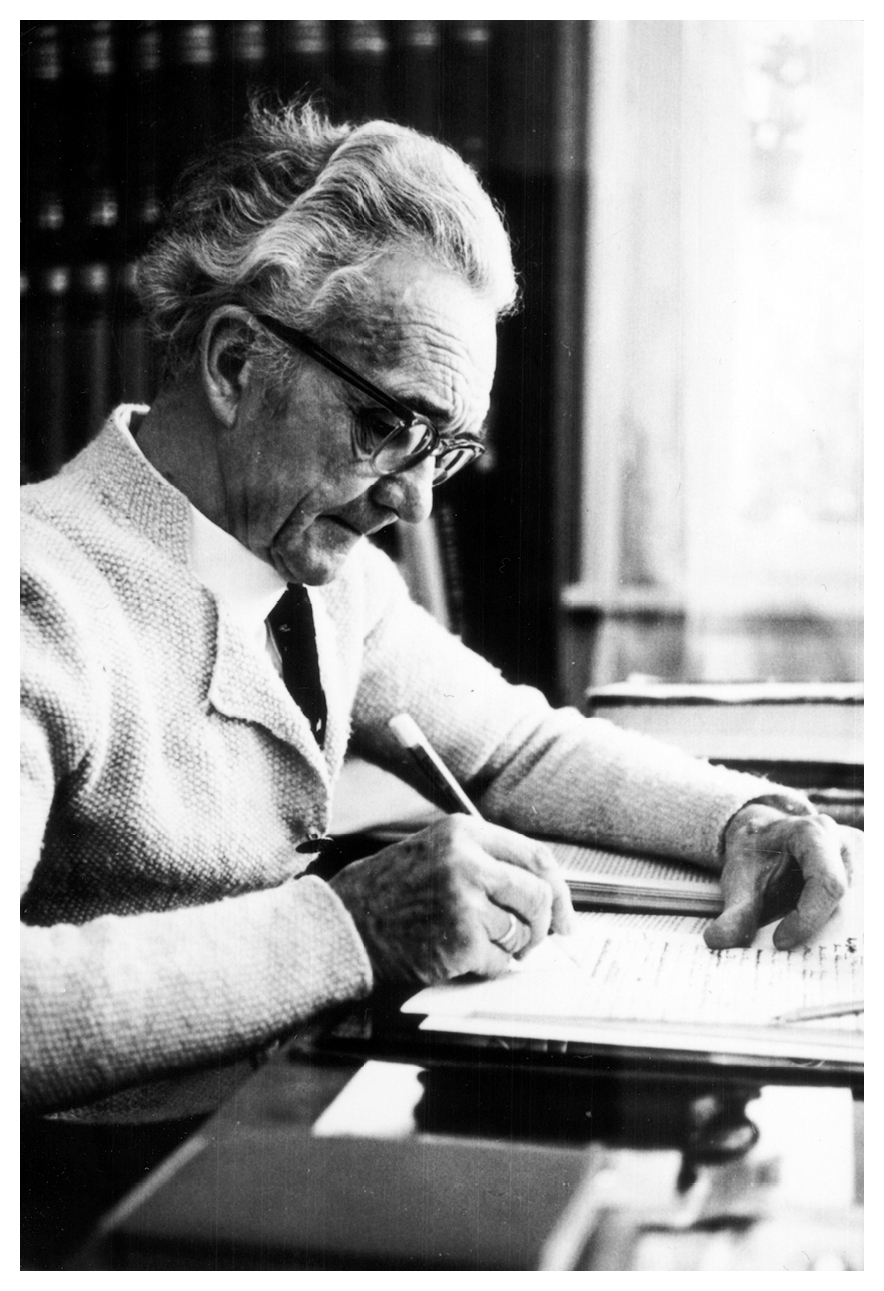

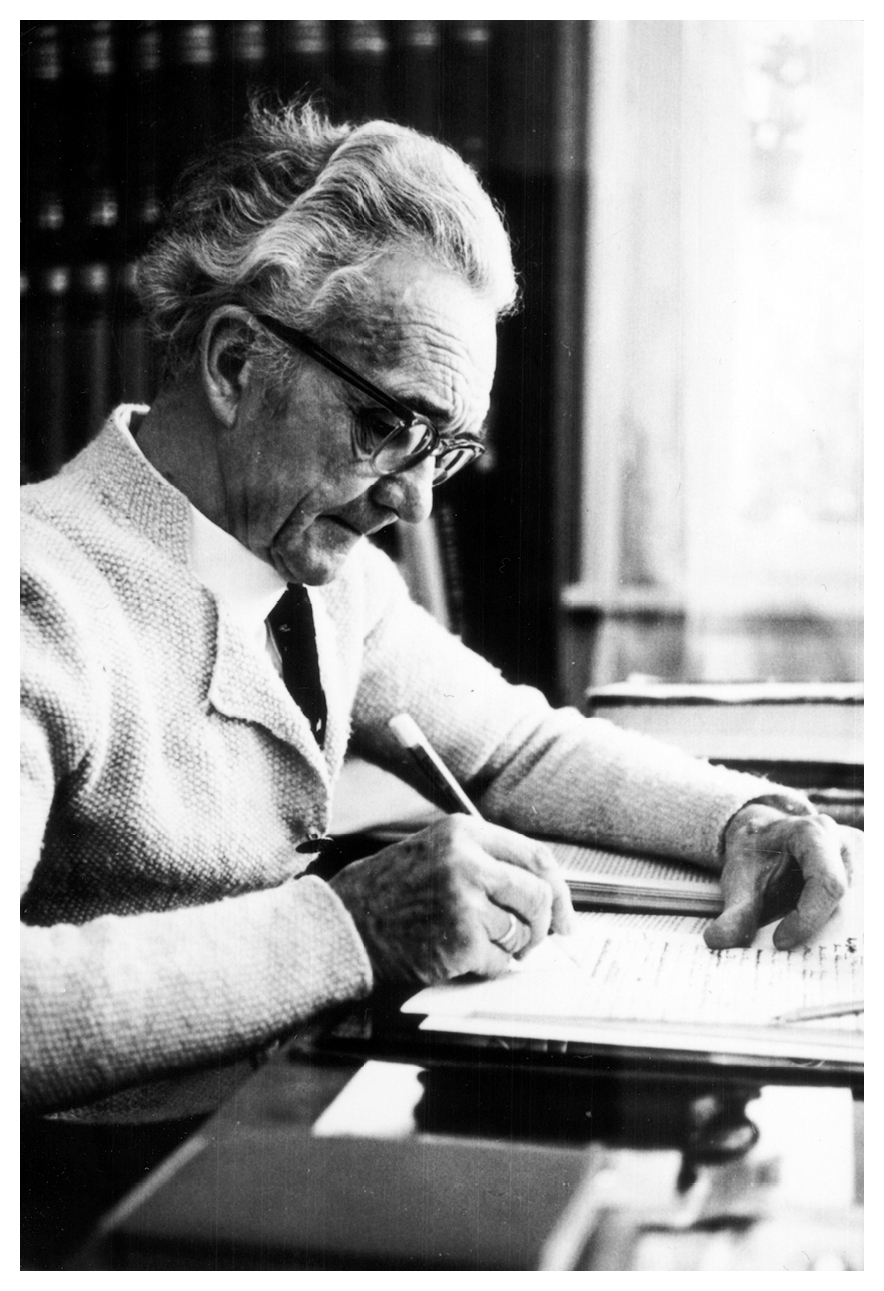

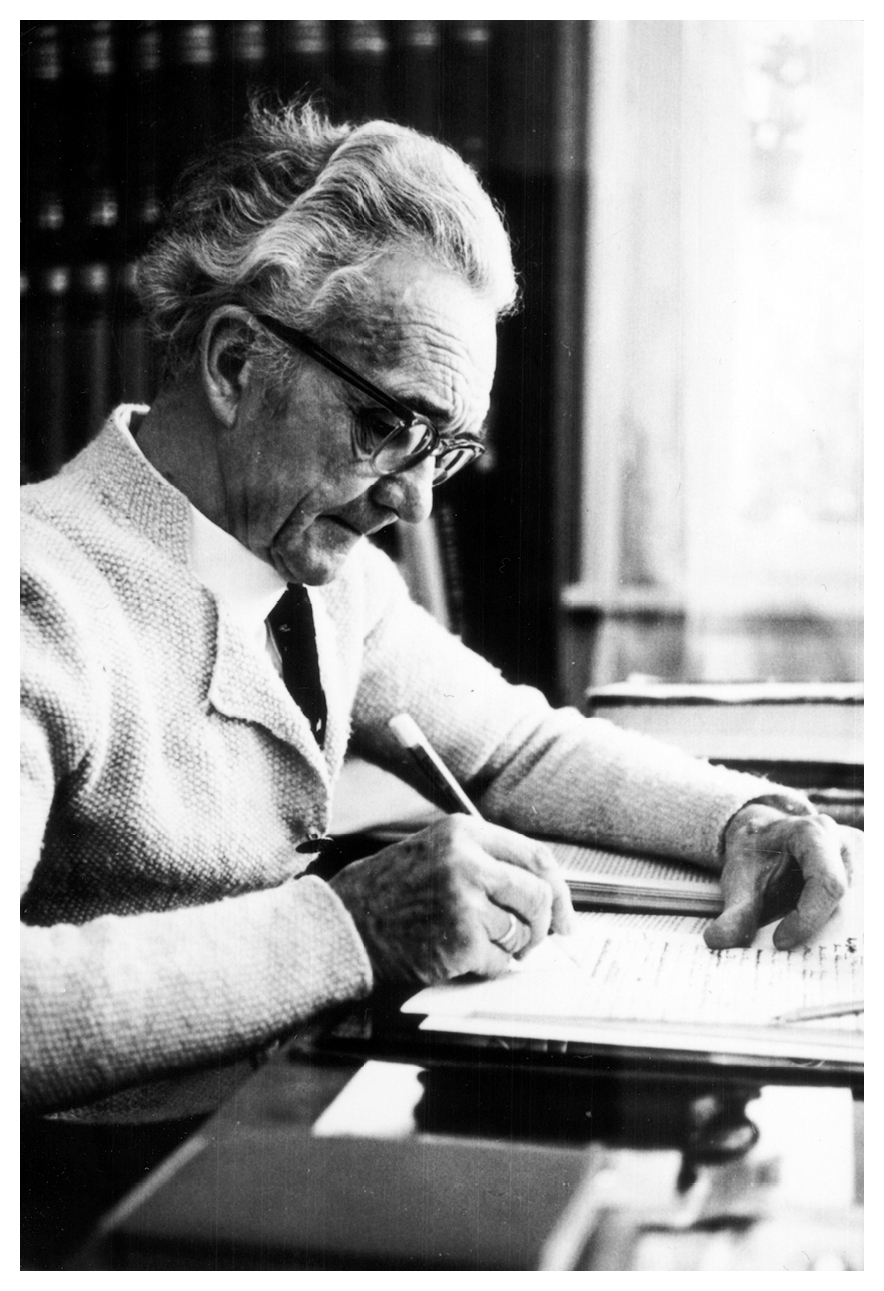

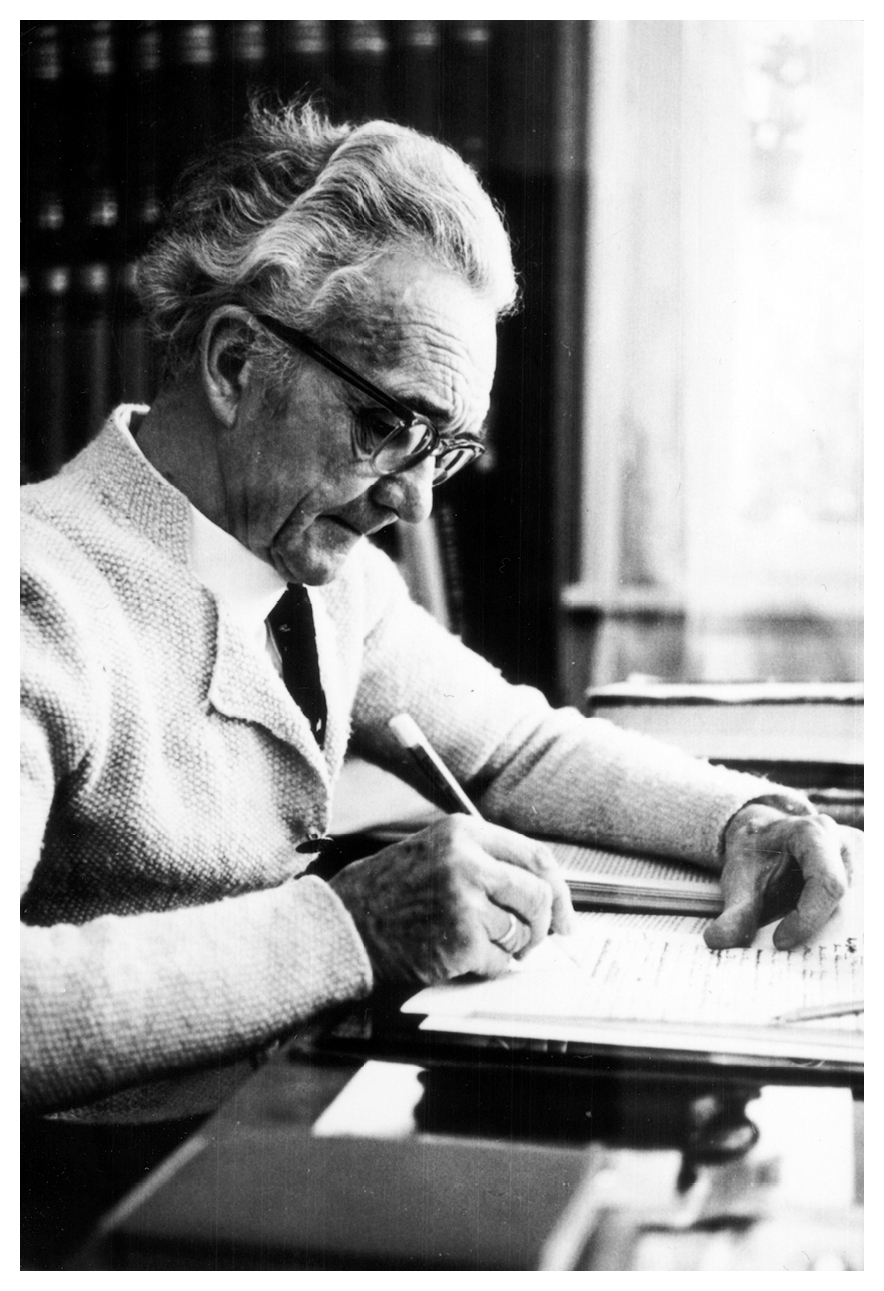

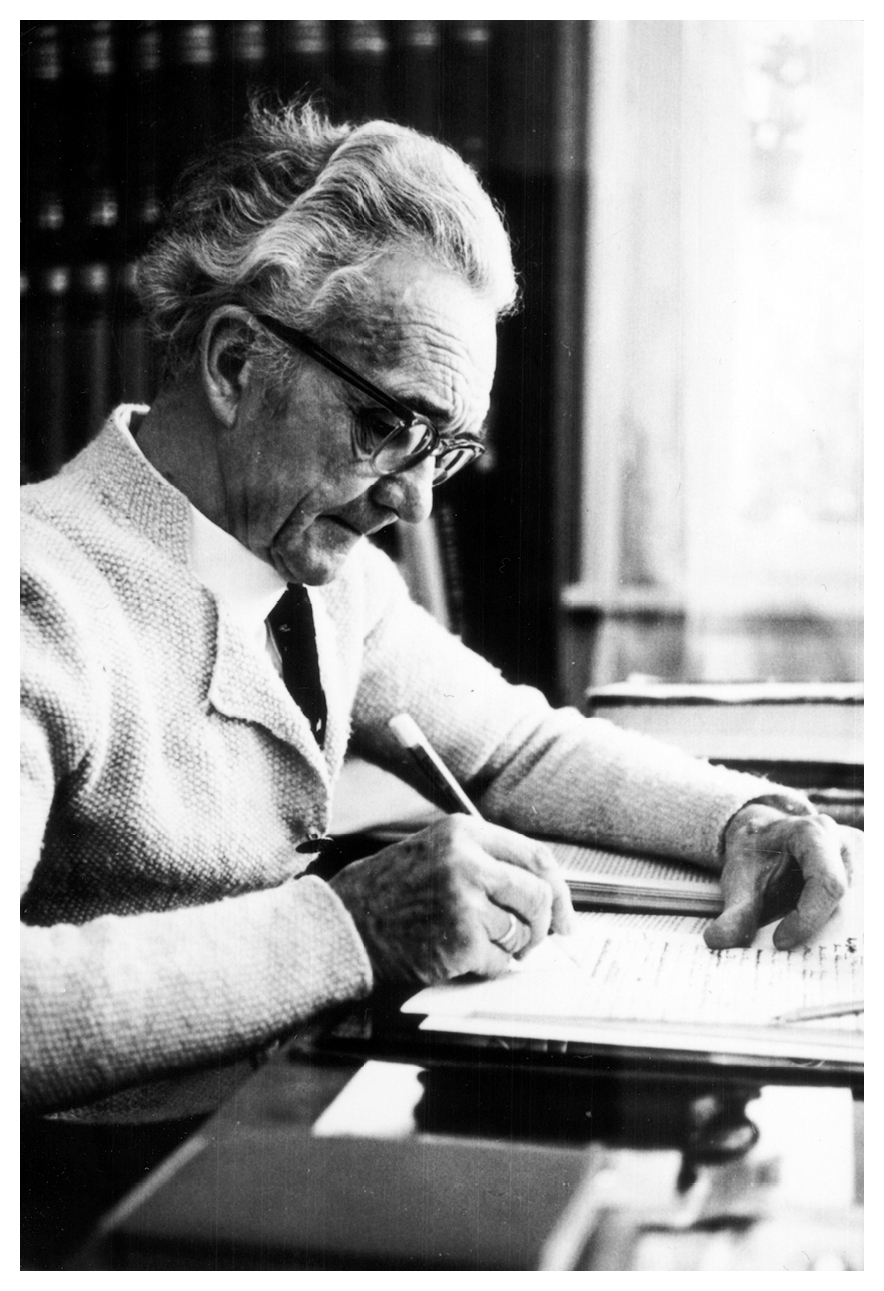

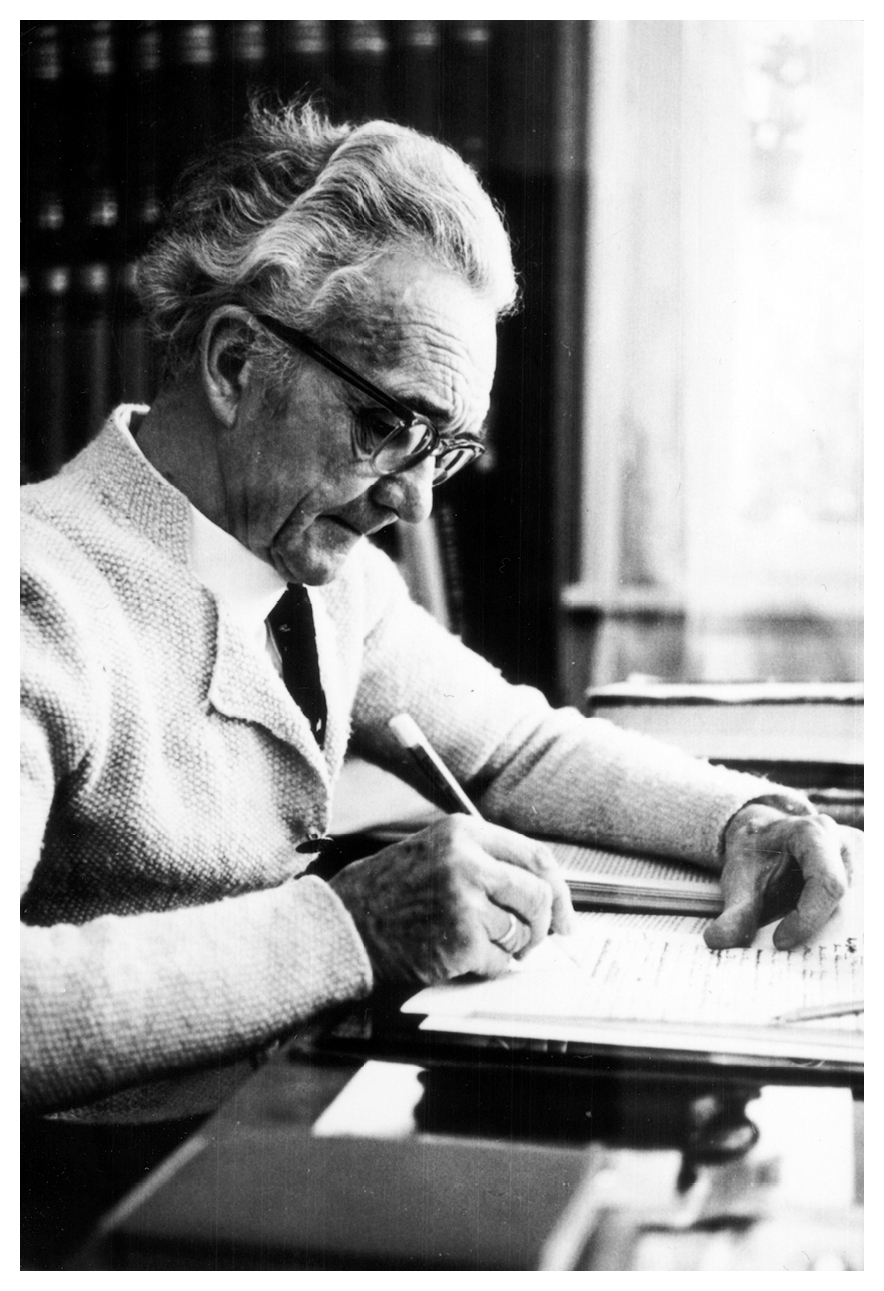

Fig. 14a. Hans Kienle (1895--1975), (Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg)

Fig. 14b. Happel Laboratory for Astrophysics (1957), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Hans Kienle (1895--1975) was professor and director in Göttingen from 1924/25, director of the Astrophysical Observatory in Potsdam. In 1950 Kienle he got the call as professor for astrophysics and astronomy at the University of Heidelberg and director of the State Observatory Heidelberg-Königstuhl. There he erected the Happel Laboratory for Astrophysics (1957), north of the main building, financed by a foundation of the Heidelberg painter Karl Happel (1819--1914), with a "black body" in order to investigate the energy distribution in the spectra of the Sun and stars, with the aim of determining an absolute temperature scale of the stars (absolute spectrophotometry). Today instruments for international observatories like ESO are developed here. After his retirement in 1962, Kienle accepted an invitation from former students to Turkey in order to help building a new observatory in Izmir.

Hans Elsässer (1929--2003), after studying at the University of Tübingen (Habilitation 1959), worked at the Swiss Jungfraujoch Observatory and at the Boyden Observatory in Bloemfontein in South Africa. From 1955 to 1956 Elsässer was on seeing expeditions in South Africa, intergrated in the plan for the ESO Southern Observatory. In 1962 he became a full professor for astronomy at the University of Heidelberg, and he was also head of the State Observatory in Heidelberg-Königstuhl until 1975. In 1968, Elsässer was the founding director of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg. He remained Managing Director of the MPI until 1997. Elsässer was involved in various rocket and balloon experiments that were necessary for the successful implementation of the Helios A and B and the Infrared Space Observatory (ISO) projects. He was interested in topics like interstellar matter, star formation, active galaxies, and large-scale structures in the universe.

Directors

- Maximilian Franz Joseph Cornelius Wolf (1863--1932), 1898 to 1932

- Heinrich Vogt (1890--1968), 1933 to 1945

- August Kopff (1882--1960), 1947 to 1950

- Hans Kienle (1895--1975), 1950 to 1962

- Hans Elsässer (1929--2003), 1962 to 1975

- Immo Appenzeller (*1940), 1975 to 2005

- Andreas Quirrenbach, since 2006

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-15 18:18:04

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The observatory is in good condition and still in active use.

There was no prominent architect involved in erecting the buildings.

The old meridian circle building, the East Institute of the observatory, was converted into an auditorium building in the 1960s,

which today also houses a small astronomical museum, where also the photographic plate archive can be found today.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-21 02:33:56

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The layout as an astronomy park is similar to Hamburg Observatory, but smaller; the strict separation like in Hamburg Observatory of the observing buildings (domes) on one side and of the office buildings, apartments, workshops on the other side is not so strict in Heidelberg, e.g. the Bruce telescope is in close connection to the main office building, another dome is on the Eastern Institute.

But the modern idea was in Heidelberg, like in American observatories, e.g. Lick on Mt. Hamilton, to place the observatory on a mountain peak far from the city center.

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-13 05:27:21

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no threats

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-20 14:14:01

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Used as astrophysical observatory. Since the 1970s, three new reflecting telescopes were added for observing.

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-21 02:32:09

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Since 1 January 2005, the Landessternwarte Königstuhl (LSW) - together with the Astronomical Computing Institute (Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, ARI) and the Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics (ITA) - is part of the Center for Astronomy (ZAH) at the University of Heidelberg.

Fig. 15a. Haus der Astronomie in the shape of the spiral galaxy M51 and MPI for Astronomy with two domes, Heidelberg-Königsstuhl, (© Haus der Astronomie)

Fig. 15. Haus der Astronomie Heidelberg-Königsstuhl, architect Manfred Bernhardt (2009/11), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

A new building on the grounds of the nearby Max Planck Institute for Astronomy Heidelberg-Königstuhl, the Haus der Astronomie, designed by the Darmstadt architect Manfred Bernhardt (Architects Bernhardt + Partner) (2009/11), has the shape of the spiral galaxy M51 -- according to the wish of the founder, Klaus Tschira, the architecture should visualize its function. The Haus der Astronomie (HdA) is a center for scientific exchange between Heidelberg researchers and the public, as well as for promoting astronomy in schools.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-01-12 22:18:29

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Albrecht, R.; Maitzen, H.-M. & Anneliese Schnell: Early Asteroid Research in Austria. 2001. Online at

http://www.stecf.org/~ralbrech/amico/papers/albrechtr/albrechtr.html.

- Appenzeller, Immo; Dubbers, Dirk; Siebig, Hans-Georg & Albrecht Winnacker (ed.): Heidelberger Physiker berichten. Rückblicke auf Forschung in der Physik und Astronomie. Heidelberg 2017.

- Bohrmann, A.: Heinrich Vogt. In: Mitteilungen der Astronomischen Gesellschaft 24 (1968), p. 7 (Nachruf).

- Curtius, Theodor & Johannes Rissom: Geschichte des Chemischen Universitäts-Laboratoriums zu Heidelberg seit der Gründung durch Bunsen. Heidelberg 1908 [UBH: F2149-10 Folio].

- Dörflinger, Gabriele: Homo Heidelbergensis mathematicus. Eine Materialsammlung zu bekannten Heidelberger Mathematikern. Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg (online).

- Dörflinger, Gabriele: Heidelberger Mathematiker-Rundgang. Heidelberg: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg (Heidelberger Texte zur Mathematikgeschichte - Epochen) 2018, http://histmath-heidelberg.de/heidelberg/mathrund-www/Welcome.html.

- Driesen, Hans Erhard [Dietrich Lemke]: Stereoaufnahmen von Max Wolf. In: Sterne und Weltraum 52 (Okt. 2013), p. 8.

- Freiesleben, Hans-Christian von: Max Wolf. Der Bahnbrecher der Himmelsphotographie. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft 1962.

- Heintze, Joachim; DeKieviet, Maarten & Jörg Hüfner: Geschichte der Physik an der Universität Heidelberg. Heidelberg: University Publishing 2019.

- Kienle, Hans: Vom Wesen astronomischer Forschung. Aufsätze und Vorträge. Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag 1948.

- Kienle, Hans: Aus der Geschichte der Naturwissenschaftlich-Mathematischen Fakultät der Universität Heidelberg: Die naturwissenschaftlichen Institute. Sternwarte auf dem Königsstuhl.

In: Ruperto-Carola: Aus der Geschichte der Universität Heidelberg und ihrer Fakultäten, Sonderband. Heidelberg: Brausdruck GmbH 1961, p. 426.

- Kistner, Adolf: Die Anfänge der Experimentalphysik an der Universität Heidelberg. In: ZGORh 89 (1937), p. 110.

- Kollnig-Schattschneider, E.: Heinrich Vogt, 5.10.1890--23.1.1968. In: Astronomische Nachrichten 292 (1970), p. 45. (Nachruf).

- Kopff, August: Max Wolf - ein Gedenkblatt. In: Sitzungsberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften 1933.

- Krafft, Fritz: Max Franz Joseph Cornelius. In: derselbe: Die bedeutend sten Astronomen. (marix wissen) Wiesbaden 2007, S. 215-218.

- Krafft, Fritz: Max Wolfs Eintritt in die scientific community der Astronomen. In: Dick, Wolfgang Dick; Schielicke, Reinhard & Chris Sterken (ed.): In memoriam Hilmar W. Duerbeck. Leipzig (Acta Historica Astronomiae, Band 64) 2014, p. 413-439.

- Lemke, Dietrich: Max Wolf "Etwas anderes als Astronom kann man eigentlich gar nicht werden ..." In: Sterne und Weltraum 52 (Juli 2013), Heft 7, p. 40-51.

- Lemke, Dietrich: Max Wolf -- Stammvater der Heidelberger Astronomie. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Der Himmel über Tübingen. Barocksternwarten -- Landesvermessung -- Astrophysik. Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft 2013. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Band 28) 2014, p. 252--279.

- Lemke, Dietrich & Kalevi Mattila: Freunde im Norden -- Max Wolfs Verbindungen zu Astronomen im Ostseeraum. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum - Astronomy in the Baltic. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis; Band 38) 2018, p. 412-417.

- Lemke, Dietrich: Im Himmel über Heidelberg. 50 Jahre Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie in Heidelberg (1969--2019). Berlin, Heidelberg (Veröffentlichungen aus dem Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft; Band 21) 2019.

- Lemke, Dietrich: Asteroid Pawona -- Ehrung einer deutsch-österreichischen Forschungsgemeinschaft im Reich der kleinen Planeten. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Internationalität in der astronomischen Forschung (18. bis 21. Jahrhundert). Internationality in the Astronomical Research (18th to 21th Century). Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis, Band 49) 2020, p. 298-301.

- Lemke, Dietrich & Thomas Henning: Astronomische Streifzüge durch Heidelberg. Von kleinen Planeten zur zweiten Erde (Morio). Heidelberg 2021.

- Oldenburg, Stefan: Mit weitem Blick. Der Astronom Max Wolf war ein wichtiger Pionier der modernen Himmelsfotografie, der seiner Geburtsstadt Heidelberg ein Leben lang treu blieb. In: Physik Journal 17 (2018) Nr. 10, p. 48-50.

- Quincke, Georg: Geschichte des physikalischen Instituts der Universität Heidelberg. Akademische Rede vom 21. November 1885. Heidelberg 1885, http://www.historische-kommission-muenchen-editionen.de/rektoratsreden/anzeige/index.php?type=rede&id=1568.

- Reichert, Uwe: Hundert Jahre Landessternwarte Heidelberg-Königstuhl. In: Sterne und Weltraum 37 (1998), Heft 12, p. 1036-1044.

- Schaifers, Karl: Max Wolf. 1863-1932. In: Semper apertus. 600 Jahre Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg 1386--1986. Festschrift in sechs Bänden. Band 3: Das zwanzigste Jahrhundert: 1918--1985. Hrsg. von Wilhelm Doerr. Berlin: Springer 1985, p. 97-113.

- Schnell, Anneliese: Überholt vom Fortschritt -- die Geschichte einer Koproduktion Heidelberg-Wien -- Die Wolf-Palisa-Karten (ein früher photographischer Himmelsatlas. In: Dick, Wolfgang R. & Jürgen Hamel (Hg.): Beiträge zur Astronomiegeschichte; Band 12. Leipzig: AVA Akademische Verlagsanstalt (Acta Historica Astronomiae; Vol. 50) 2014, S. 151-166. ADS Record:

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2014AcHA...50..151S.

- Sears, Frederick Hanley: Awarding the Bruce Medal to Professor Max Wolf. In: Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 42 (Februar 1930), p. 5-22.

- Umland, Regina: "Überholt vom Fortschritt - die Geschichte einer Koproduktion Heidelberg-Wien" -- Die Wolf-Palisa-Karten (ein früher photographischer Himmelsatlas). In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Internationalität in der astronomischen Forschung (18. bis 21. Jahrhundert). Internationality in the Astronomical Research (18th to 21th Century). Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis, Band 49) 2020, p. 302-324.

- Vogt, Heinrich: Aufbau und Entwicklung der Sterne. Leipzig: Becker & Erler 1943, Leipzig: Geest & Portig (2. Auflage) 1957.

- Wielen, Roland & Ute Wielen: Von Berlin über Sermuth nach Heidelberg. Heidelberg 2012.

- Wielen, Roland & Ute Wielen: August Kopff, the Theory of Relativity, and two Letters from Albert Einstein to Kopff in the Archives of the Astronomisches Rechen-Institut. Heidelberg: Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg 2013.

HeiDOK - Der Heidelberger Dokumentenserver, http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/volltextserver/15653/1/Kopff_Einstein_1.pdf.

- Wolf, Max: Ueber grosse Nebelmassen im Sternbilde des Schwans. In: Astronomische Nachrichten 127 (1891), Nr. 23-24, p. 427-428.

- Wolf, Max: Die Photographie der Planetoiden. In: Astronomische Nachrichten (1895), Nr. 3319.

- Wolf, Max: Die Milchstrasse und die kosmischen Nebel: 16 Lichtdrucke nach Himmelsphotographien mit erläuterndem Text. Potsdam 1925. https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.17541.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Max Wolf (1863-1932) as a Pioneer of Astrophotography. In: Schielicke, Reinhard E. (ed.): Astronomische Gesellschaft - Abstract Series No. 14 (1998). Hamburg 1998, p. 80.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Astronomisches Mäzenatentum. Proceedings der Tagung an der Kuffner-Sternwarte in Wien, ,,Astronomisches Mäzenatentum in Europa’’, 7.--9. Oktober 2004. Norderstedt: Books on Demand (Nuncius Hamburgensis - Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 11) 2008.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Cultural Heritage of Astronomical Observatories -- From Classical Astronomy to Modern Astrophysics. Proceedings of International ICOMOS Symposium in Hamburg, October 14--17, 2008. Berlin: hendrik Bäßler-Verlag (International Council on Monuments and Sites, Monuments and Sites XVIII) 2009.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 7

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-07-22 17:21:06

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Landessternwarte Königstuhl (LSW)

- Center for Astronomy (ZAH) at the University of Heidelberg

- Das Leuchten der Sterne fixiert -- Die historische Fotoplattensammlung der Landessternwarte Heidelberg-Königstuhl

- Zur Geschichte der Astronomie in der Kurpfalz, Förderkreis Landessternwarte Heidelberg e.V.

- Max Wolf, Bergfriedhof Heidelberg

- Max Wolf, Heidelberger Geschichtsverein e.V.

- Kleinplanetenentdeckungen in Heidelberg: Beobachtungen von Asteroiden haben in Heidelberg eine lange Tradition. Bis heute ist der Observatory Code 024 der Standort mit den meisten Nummerierungen in Deutschland.

- Privatsternwarte von Max Wolf in Heidelberg-Märzgasse

- Wolf, Maximilian (Max) Franz Joseph Cornelius, LEO-BW.de

- Gabriele Dörflinger: Märzgasse 16 - Max Wolf, Heidelberger Mathematiker Rundgang - Historia Mathematica Heidelbergensis

- Klaus Wenzel: Der Wolfsche Sechszöller -- Der Lebenslauf eines historischen Teleskops

- HDAP -- Heidelberg Digitized Astronomical Plates

- Milcho Tsvetkov: Wolf-Palisa Survey: The Wolf-Palisa stellar charts were produced between 1900 and 1916 in a collaboration between the Heidelberg and Vienna Observatories for the needs of minor planets observations.

Links to external on-line pictures - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-08-17 10:23:21

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no information available

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-20 14:33:16

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Heidelberg-Königstuhl State Observatory (Landessternwarte Heidelberg-Königstuhl),

Center for Astronomy (ZAH) at the University of Heidelberg,

Königstuhl 12, D-69117 Heidelberg, Germany

Additional places connected to astronomy in Heidelberg:

- Max Wolf’s birthplace and private observatory, Märzgasse 16

- Laboratory of Kirchhoff and Bunsen (1858), "Haus zum Riesen", Johann Adam Breunig (1707/08), Hauptstr. 52

- Bergfriedhof, Grab Max Wolf, Rundweg IV, 26.

Location - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-20 14:34:37

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude 49°23’54’’ N, Longitude 08°43’29’’ E, Elevation 566m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-08-17 10:23:20

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

024

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 16

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-05-25 18:42:01

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 1a. Laboratory of Kirchhoff and Bunsen (1858), Hauptstr. 52 (DChG)

Fig. 1b. Laboratory of Kirchhoff and Bunsen (1858), "Haus zum Riesen", Johann Adam Breunig (1707/08), Hauptstr. 52 (Wikipedia)

In Heidelberg, the method of spectral analysis was invented by Kirchhoff and Bunsen (1859); their Laboratory was since 1868 in the "Haus zum Riesen", Johann Adam Breunig (1707/08), Hauptstr. 52.

Max Wolf’s private observatory, Märzgasse 16

Fig. 2a. Max Wolf’s birthplace, Märzgasse 16 (Wikipedia, CC4, Ribax)

Fig. 2b. Max Wolf’s private observatory, Märzgasse 16 (1885), (Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Heid. Hs. 3695/B,5, Nachlass Max Wolf 0179)

Fig. 2c. Max Wolf’s private observatory, Märzgasse 16 (1885), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 2d. 6-inch-Astrograph - two portrait cameras (1892/93) in the white dome in Königsstuhl (Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Heid. Hs. 3695)

Fig. 2e. Max Wolf’s private observatory, 6-inch-Double Astrograph, consisting of two portrait cameras, made by Voigtländer of Braunschweig (1892), now as a museum object in Heidelberg-Königsstuhl Observatory (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Max Wolf’s birthplace, built in 1836, and private observatory (1885) can be found in Märzgasse 16 in Heidelberg.

The double astrograph was put into operation by Max Wolf in February 1892. The astrograph consisted of two 6-inch-portrait lenses made by Voigtländer of Braunschweig. They had an aperture ratio of f/5. The field of view was approximately 70 square degrees and thus covered an unusually large section of the sky for that time. The guiding telescope was used for tracking during the recordings. With this instrument, Max Wolf discovered, among other things, the North American nebula NGC7000 and many new minor planets (planetoids, asteroids). Minor planets revealed themselves on the exposed photographic plates by small traces of lines, due to their own motion during the relatively long exposure time, which could well be a few hours.

Wolf’s instruments, the double astrograph, consisting of two portrait cameras and a guiding telescope, are preserved in Heidelberg-Königsstuhl Observatory.

Großherzogliche Bergsternwarte / Landessternwarte Heidelberg

Fig. 3. Heidelberg Observatory (LSW, Uni HD)

Fig.: Heidelberg Observatory (LSW, Uni HD)

Thanks to the activity of Grand Duke Friedrich I of Baden (1826--1907), the Heidelberg State Observatory (Großherzogliche Bergsternwarte, later: Landessternwarte Heidelberg) was built on the Königstuhl (elevation 566m). On June 20, 1898, the Grand Ducal Mountain Observatory on the Königstuhl was inaugurated in the presence of the Grand Duke Friedrich I of Baden. Heidelberg was one of the first mountain observatories in Europe after Nice Observatory and comparable to the American mountain observatories like Lick.

First light on the Königsstuhl was on June 28, 1898.

Fig. 4. Map of Heidelberg Observatory (LSW, Uni HD)

There were two scientific departments: The Astrometric Institute with the meridian instruments and slits (East Institute), headed by Karl Valentiner (1845--1931) and the Astrophysical Institute (West Institute) under Max Wolf. After Valentin’s retirement (1909), Max Wolf headed the entire institute.

The original instrumentation of Heidelberg Observatory came from Mannheim Observatory, founded in 1774, which had been relocated to Karlsruhe in 1880 due to the increasing deterioration of observation conditions.

Fig. 5. Entrance gate of Heidelberg Observatory (© Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

With the main instruments, the Bruce astrograph (August 16, 1900) and the Waltz reflector (1906) -- both financed by private foundations -- the institute was one of the most modern research facilities in the world at the time.

Max Wolf (1863--1932)

Fig. 6. Max Wolf (1863--1932), (Wikipedia)

Maximilian Franz Joseph Cornelius Wolf (1863--1932) studied physics as scholar of Georg Hermann Quincke (1834--1924) in Heidelberg, astronomy in Strasbourg, and did his doctorate in Heidelberg under the mathematician Leo Königsberger (1837--1921). Max Wolf initiated astrophysics in Heidelberg at the end of the 19th century, especiallly as a pioneer of photography. While still a student, he discovered in his private observatory the periodic comet 14P/Wolf, named after him.

Since 1893 Wolf was an associate professor at Heidelberg University. He turned down appointments to Göttingen and Vienna university Observatories. The astronomical institute initially consisted of two competing departments, the astrophysical under Max Wolf and the astrometric under Wilhelm Valentiner (1845--1931), who was first director in Mannheim and from 1880 to 1909 director of Karlsruhe Observatory. But after Valentin’s retirement in 1909, the departments were merged under the direction of Max Wolf until 1932.

Fig. 7a. North America Nebula NGC 7000 in the constellation Cygnus (1891), 13 hours exposure time (Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Wolf 1925, 0035)

Fig. 7b. Types of nebulae, defined by Max Wolf in 1908 (LSW Heidelberg)

The celestial photography developed by Max Wolf made epochal discoveries possible, such as that of the North America Nebula in the constellation Cygnus (1891), the rediscovery of Halley’s Comet (1909), numerous variable stars are found, studies of the tail structure and spectra brought new knowledge about comets, followed by studies of the structure of the Milky Way system. Large nebulae in the constellations Orion, Cygnus and Auriga are discovered on photographic plates. Spectra reveal that "nebulae" are gas structures like Huggins had already proposed in 1864. For his remarkable photographic recordings, Wolf was awarded with gold medals at the world exhibitions in Paris (1900) and St. Louis (1904).

Fig. 8. Max Wolf’s Spectrum of the Andromeda nebula (1911), 25 hours exposure time (Sitzungsberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften, Math.-Naturwiss. Klasse, Abt. A, 1912)

In spiral nebulae like Andromeda, recognized by Julius Scheiner (1858-1913) as stellar system outside of our Milky Way, the systematic shift in the spectral lines was recognized by Max Wolf (1913). Wolf developed the blink comparator together with Carl Pulfrich (1858--1927) from the Zeiss company. By quickly comparing two photo plates, changes in positions are obvious and thus comets and asteroids could be discovered, in addition, variable stars could be recognized due to the blinking effect. Wolf discovered ten novae in this way.

Fig. 9a. Blink comparator, Carl Zeiss of Jena (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 9b. Comet Morehouse (1908), Stereoscopic images (1913) (LSW Heidelberg)

Fig. 9c. Asteroid (323) Brucia, the first asteroid, discovered by Max Wolf using the photographic method in 1891, model, Haus der Astronomie (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Up until the 1950s, the emphasis of Max Wolf’s research was concentrated on asteroids: around 800 were discovered on photographic plates in the Königstuhl Observatory by Max Wolf and his cooperators, including the first Jupiter Trojan Asteroid 588 Achilles in 1906.

The asteroid (323) Brucia, discovered by Max Wolf on December 22, 1891, was the first asteroid using the photographic method, and the lunar crater Bruce were named in memory of the donation of the Bruce Reflector by Catherine Wolfe Bruce (1816--1900).

Fig. 10. Catherine Wolfe Bruce (1816--1900), (Wikipedia)

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 10

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-15 18:37:22

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 11. Six domes of Heidelberg Observatory (Wikipedia, CC3, Mhdman)

In 1898, the "Großherzogliche Bergsternwarte" (Grand Ducal Mountain Observatory) was inaugurated by Grand Duke Friedrich I of Baden.

Fig. 12a. Kann Refractor Building (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12b. 8-inch-Kann Refractor, Merz of Munich (Photo: Werner Zigs)

Fig. 12c. Bruce-Telescope Dome (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12d. 40-cm-Bruce photographic double refractor (1900), 1900 -- donated by Catherine Wolfe Bruce (1816--1900) of New York (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12e. 40-cm-Bruce double astrograph (1900), 1900 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12f. 40-cm-Bruce double astrograph (1900), 1900 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12g. Zeiss-Telescope Building (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12h. Waltz-Telescope Building - just in restoration (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12i. 72cm-Waltz-Telescope (Newton), Nasmyth-Focus, Carl Zeiss of Jena (1906) (LSW Heidelberg)

Instruments

- 6-inch-Refractor (1859), used for the visual observation of double stars, later was used until 1924 to measure star clusters like globular clusters, and then for teaching and training purposes; in 1957, the 6-inch-Refractor was donated to the public observatory in Karlsruhe.

- Max Wolf’s instrument from his private observatory: 6-inch-Double Astrograph, consisting of two portrait cameras, made by Voigtländer of Braunschweig (1892 and 1893), and a guiding telescope, Reinfelder & Hertel of Munich, on a German mounting, made by "M. Sendtner of Munich" in a 5-m-dome; he added also smaller objectives like 5-inch-Kranz and 61-mm-Steinheil. The 6-inch-astrograph was used on Königsstuhl from 1898 until 1960, first in a white dome, then since 1919 in a black dome. The last photographic plate was exposed on June 16, 1939, for 4 minutes, it showed the variable star P Cygni.

- 8-inch-Kann Refractor (20-cm diameter, 300-cm focal length), wooden tube, German mounting, Merz, Munich -- the oldest telescope of the Landessternwarte, already mentioned in the annual report of 1894 of the Karlsruhe Observatory, donated by L. Kann.

- 40-cm-Bruce-Telescope (16-inch, focal length 2m), a photographic double refractor (astro camera), diameter of the photographic lenses 40-cm, visual guiding telescope (objective diameter 25-cm, focal length 4-m), first light August 1900 -- donated by Catherine Wolfe Bruce (1816--1900) of New York. Thousands of photographic plates were taken with this astrograph.

- 72cm-Waltz-Telescope (Newton), Nasmyth-Focus, Carl Zeiss of Jena (1906) with a two-prism-Spectrograph.

It was the first "large" reflector, made by Carl Zeiss of Jena; shortly afterwards, 1911, the Hamburg 1-m-Reflector was built.

- Schmidt telescope (main mirror diameter 40-cm, diameter of the correction plate 25-cm, focal length 90-cm (f:3.6), produced in the Heidelberg workshop (1963), large field of view (4°), used with objective lens prism

- 50-cm-Cassegrain Reflector, main mirror diameter 50-cm, focal length 6.95-m (f:14), produced in the Heidelberg workshop (1978), used for stellar photometry and polarimetry.

Until 1978, a 12-inch-refractor (4.22-m focal length), Steinheil, donated by Kreßmann, was used as guiding telescope.

- 75-cm Ritchey-Chretien-Cassegrain-Telescope (focal length 6-m, f:8), Carl Zeiss of Oberkochen (1977), used with CCD, used since 2005 in the ATOM-Project in Namibia

- 70-cm Cassegrain Reflecting telescope (focal length 5.6-m, f:8), (1988), used with CCD camera.

- Stereokomparator, Carl Zeiss of Jena

- Pendulum clocks: Chronometerwerke GmbH, Ferdinand Dencker, No. 52 (sidereal time), S. Riefler, No. 44, Munich (1899), Clemens Riefler, No. 523, Munich (1928)

Fig. 13a. Main Building (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13b. Waltz Reflector building and memorial plaque Max Wolf (1953), (Photo: Dietrich Lemke)

Fig. 13c. Zeiss Telescope Building and Bruce Dome (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13d. East Institute and Schmidt Telescope dome and two Cassegrain domes (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13e. East Institute and Cassegrain dome (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13f. Pendulum clock Chronometerwerke GmbH, Ferdinand Dencker, No. 52 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13g. Pendulum clock S. Riefler, No. 44, Munich (1899), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13h. Pendulum clock Clemens Riefler, No. 523, Munich (1928), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

After Wolf’s death (1932), the theorical astronomer Heinrich Vogt (1890--1968) was entrusted with the management of the observatory. His research was in stellar structure (Vogt-Russell-Theorem). In 1931, he became a member of the NSDAP, and in 1933, he became a member of the SA (Obersturmführer). In 1933, he got the call as full professor at the University of Heidelberg.

August Kopff (1882--1960), a former student of Max Wolf and director of the Astronomical Computing Institute (Astronomisches Recheninstitut, ARI), 1924 to 1954 in Berlin, and since 1945 in Heidelberg, took over the management of Heidelberg Observatory. He discovered Kopff’s comet in 1906 (rendezvous of the Galileo space probe), and 66 asteroids in the period from 1905 to 1909. But he was already in the 1920s interested in the General Theory of Relativity, gave lectures and published a textbooks.

Fig. 14a. Hans Kienle (1895--1975), (Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg)

Fig. 14b. Happel Laboratory for Astrophysics (1957), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Hans Kienle (1895--1975) was professor and director in Göttingen from 1924/25, director of the Astrophysical Observatory in Potsdam. In 1950 Kienle he got the call as professor for astrophysics and astronomy at the University of Heidelberg and director of the State Observatory Heidelberg-Königstuhl. There he erected the Happel Laboratory for Astrophysics (1957), north of the main building, financed by a foundation of the Heidelberg painter Karl Happel (1819--1914), with a "black body" in order to investigate the energy distribution in the spectra of the Sun and stars, with the aim of determining an absolute temperature scale of the stars (absolute spectrophotometry). Today instruments for international observatories like ESO are developed here. After his retirement in 1962, Kienle accepted an invitation from former students to Turkey in order to help building a new observatory in Izmir.

Hans Elsässer (1929--2003), after studying at the University of Tübingen (Habilitation 1959), worked at the Swiss Jungfraujoch Observatory and at the Boyden Observatory in Bloemfontein in South Africa. From 1955 to 1956 Elsässer was on seeing expeditions in South Africa, intergrated in the plan for the ESO Southern Observatory. In 1962 he became a full professor for astronomy at the University of Heidelberg, and he was also head of the State Observatory in Heidelberg-Königstuhl until 1975. In 1968, Elsässer was the founding director of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg. He remained Managing Director of the MPI until 1997. Elsässer was involved in various rocket and balloon experiments that were necessary for the successful implementation of the Helios A and B and the Infrared Space Observatory (ISO) projects. He was interested in topics like interstellar matter, star formation, active galaxies, and large-scale structures in the universe.

Directors

- Maximilian Franz Joseph Cornelius Wolf (1863--1932), 1898 to 1932

- Heinrich Vogt (1890--1968), 1933 to 1945

- August Kopff (1882--1960), 1947 to 1950

- Hans Kienle (1895--1975), 1950 to 1962

- Hans Elsässer (1929--2003), 1962 to 1975

- Immo Appenzeller (*1940), 1975 to 2005

- Andreas Quirrenbach, since 2006

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-15 18:18:04

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The observatory is in good condition and still in active use.

There was no prominent architect involved in erecting the buildings.

The old meridian circle building, the East Institute of the observatory, was converted into an auditorium building in the 1960s,

which today also houses a small astronomical museum, where also the photographic plate archive can be found today.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-21 02:33:56

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The layout as an astronomy park is similar to Hamburg Observatory, but smaller; the strict separation like in Hamburg Observatory of the observing buildings (domes) on one side and of the office buildings, apartments, workshops on the other side is not so strict in Heidelberg, e.g. the Bruce telescope is in close connection to the main office building, another dome is on the Eastern Institute.

But the modern idea was in Heidelberg, like in American observatories, e.g. Lick on Mt. Hamilton, to place the observatory on a mountain peak far from the city center.

Threats or potential threats - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 2

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-09-13 05:27:21

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no threats

Present use - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-20 14:14:01

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Used as astrophysical observatory. Since the 1970s, three new reflecting telescopes were added for observing.

Astronomical relevance today - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-21 02:32:09

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Since 1 January 2005, the Landessternwarte Königstuhl (LSW) - together with the Astronomical Computing Institute (Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, ARI) and the Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics (ITA) - is part of the Center for Astronomy (ZAH) at the University of Heidelberg.

Fig. 15a. Haus der Astronomie in the shape of the spiral galaxy M51 and MPI for Astronomy with two domes, Heidelberg-Königsstuhl, (© Haus der Astronomie)

Fig. 15. Haus der Astronomie Heidelberg-Königsstuhl, architect Manfred Bernhardt (2009/11), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

A new building on the grounds of the nearby Max Planck Institute for Astronomy Heidelberg-Königstuhl, the Haus der Astronomie, designed by the Darmstadt architect Manfred Bernhardt (Architects Bernhardt + Partner) (2009/11), has the shape of the spiral galaxy M51 -- according to the wish of the founder, Klaus Tschira, the architecture should visualize its function. The Haus der Astronomie (HdA) is a center for scientific exchange between Heidelberg researchers and the public, as well as for promoting astronomy in schools.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles) - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 8

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-01-12 22:18:29

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Albrecht, R.; Maitzen, H.-M. & Anneliese Schnell: Early Asteroid Research in Austria. 2001. Online at

http://www.stecf.org/~ralbrech/amico/papers/albrechtr/albrechtr.html.

- Appenzeller, Immo; Dubbers, Dirk; Siebig, Hans-Georg & Albrecht Winnacker (ed.): Heidelberger Physiker berichten. Rückblicke auf Forschung in der Physik und Astronomie. Heidelberg 2017.

- Bohrmann, A.: Heinrich Vogt. In: Mitteilungen der Astronomischen Gesellschaft 24 (1968), p. 7 (Nachruf).

- Curtius, Theodor & Johannes Rissom: Geschichte des Chemischen Universitäts-Laboratoriums zu Heidelberg seit der Gründung durch Bunsen. Heidelberg 1908 [UBH: F2149-10 Folio].

- Dörflinger, Gabriele: Homo Heidelbergensis mathematicus. Eine Materialsammlung zu bekannten Heidelberger Mathematikern. Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg (online).

- Dörflinger, Gabriele: Heidelberger Mathematiker-Rundgang. Heidelberg: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg (Heidelberger Texte zur Mathematikgeschichte - Epochen) 2018, http://histmath-heidelberg.de/heidelberg/mathrund-www/Welcome.html.

- Driesen, Hans Erhard [Dietrich Lemke]: Stereoaufnahmen von Max Wolf. In: Sterne und Weltraum 52 (Okt. 2013), p. 8.

- Freiesleben, Hans-Christian von: Max Wolf. Der Bahnbrecher der Himmelsphotographie. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft 1962.

- Heintze, Joachim; DeKieviet, Maarten & Jörg Hüfner: Geschichte der Physik an der Universität Heidelberg. Heidelberg: University Publishing 2019.

- Kienle, Hans: Vom Wesen astronomischer Forschung. Aufsätze und Vorträge. Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag 1948.

- Kienle, Hans: Aus der Geschichte der Naturwissenschaftlich-Mathematischen Fakultät der Universität Heidelberg: Die naturwissenschaftlichen Institute. Sternwarte auf dem Königsstuhl.

In: Ruperto-Carola: Aus der Geschichte der Universität Heidelberg und ihrer Fakultäten, Sonderband. Heidelberg: Brausdruck GmbH 1961, p. 426.

- Kistner, Adolf: Die Anfänge der Experimentalphysik an der Universität Heidelberg. In: ZGORh 89 (1937), p. 110.

- Kollnig-Schattschneider, E.: Heinrich Vogt, 5.10.1890--23.1.1968. In: Astronomische Nachrichten 292 (1970), p. 45. (Nachruf).

- Kopff, August: Max Wolf - ein Gedenkblatt. In: Sitzungsberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften 1933.

- Krafft, Fritz: Max Franz Joseph Cornelius. In: derselbe: Die bedeutend sten Astronomen. (marix wissen) Wiesbaden 2007, S. 215-218.

- Krafft, Fritz: Max Wolfs Eintritt in die scientific community der Astronomen. In: Dick, Wolfgang Dick; Schielicke, Reinhard & Chris Sterken (ed.): In memoriam Hilmar W. Duerbeck. Leipzig (Acta Historica Astronomiae, Band 64) 2014, p. 413-439.

- Lemke, Dietrich: Max Wolf "Etwas anderes als Astronom kann man eigentlich gar nicht werden ..." In: Sterne und Weltraum 52 (Juli 2013), Heft 7, p. 40-51.

- Lemke, Dietrich: Max Wolf -- Stammvater der Heidelberger Astronomie. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Der Himmel über Tübingen. Barocksternwarten -- Landesvermessung -- Astrophysik. Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft 2013. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis -- Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Band 28) 2014, p. 252--279.

- Lemke, Dietrich & Kalevi Mattila: Freunde im Norden -- Max Wolfs Verbindungen zu Astronomen im Ostseeraum. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum - Astronomy in the Baltic. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis; Band 38) 2018, p. 412-417.

- Lemke, Dietrich: Im Himmel über Heidelberg. 50 Jahre Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie in Heidelberg (1969--2019). Berlin, Heidelberg (Veröffentlichungen aus dem Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft; Band 21) 2019.

- Lemke, Dietrich: Asteroid Pawona -- Ehrung einer deutsch-österreichischen Forschungsgemeinschaft im Reich der kleinen Planeten. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Internationalität in der astronomischen Forschung (18. bis 21. Jahrhundert). Internationality in the Astronomical Research (18th to 21th Century). Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis, Band 49) 2020, p. 298-301.

- Lemke, Dietrich & Thomas Henning: Astronomische Streifzüge durch Heidelberg. Von kleinen Planeten zur zweiten Erde (Morio). Heidelberg 2021.

- Oldenburg, Stefan: Mit weitem Blick. Der Astronom Max Wolf war ein wichtiger Pionier der modernen Himmelsfotografie, der seiner Geburtsstadt Heidelberg ein Leben lang treu blieb. In: Physik Journal 17 (2018) Nr. 10, p. 48-50.

- Quincke, Georg: Geschichte des physikalischen Instituts der Universität Heidelberg. Akademische Rede vom 21. November 1885. Heidelberg 1885, http://www.historische-kommission-muenchen-editionen.de/rektoratsreden/anzeige/index.php?type=rede&id=1568.

- Reichert, Uwe: Hundert Jahre Landessternwarte Heidelberg-Königstuhl. In: Sterne und Weltraum 37 (1998), Heft 12, p. 1036-1044.

- Schaifers, Karl: Max Wolf. 1863-1932. In: Semper apertus. 600 Jahre Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg 1386--1986. Festschrift in sechs Bänden. Band 3: Das zwanzigste Jahrhundert: 1918--1985. Hrsg. von Wilhelm Doerr. Berlin: Springer 1985, p. 97-113.

- Schnell, Anneliese: Überholt vom Fortschritt -- die Geschichte einer Koproduktion Heidelberg-Wien -- Die Wolf-Palisa-Karten (ein früher photographischer Himmelsatlas. In: Dick, Wolfgang R. & Jürgen Hamel (Hg.): Beiträge zur Astronomiegeschichte; Band 12. Leipzig: AVA Akademische Verlagsanstalt (Acta Historica Astronomiae; Vol. 50) 2014, S. 151-166. ADS Record:

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2014AcHA...50..151S.

- Sears, Frederick Hanley: Awarding the Bruce Medal to Professor Max Wolf. In: Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 42 (Februar 1930), p. 5-22.

- Umland, Regina: "Überholt vom Fortschritt - die Geschichte einer Koproduktion Heidelberg-Wien" -- Die Wolf-Palisa-Karten (ein früher photographischer Himmelsatlas). In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Internationalität in der astronomischen Forschung (18. bis 21. Jahrhundert). Internationality in the Astronomical Research (18th to 21th Century). Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis, Band 49) 2020, p. 302-324.

- Vogt, Heinrich: Aufbau und Entwicklung der Sterne. Leipzig: Becker & Erler 1943, Leipzig: Geest & Portig (2. Auflage) 1957.

- Wielen, Roland & Ute Wielen: Von Berlin über Sermuth nach Heidelberg. Heidelberg 2012.

- Wielen, Roland & Ute Wielen: August Kopff, the Theory of Relativity, and two Letters from Albert Einstein to Kopff in the Archives of the Astronomisches Rechen-Institut. Heidelberg: Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg 2013.

HeiDOK - Der Heidelberger Dokumentenserver, http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/volltextserver/15653/1/Kopff_Einstein_1.pdf.

- Wolf, Max: Ueber grosse Nebelmassen im Sternbilde des Schwans. In: Astronomische Nachrichten 127 (1891), Nr. 23-24, p. 427-428.

- Wolf, Max: Die Photographie der Planetoiden. In: Astronomische Nachrichten (1895), Nr. 3319.

- Wolf, Max: Die Milchstrasse und die kosmischen Nebel: 16 Lichtdrucke nach Himmelsphotographien mit erläuterndem Text. Potsdam 1925. https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.17541.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Max Wolf (1863-1932) as a Pioneer of Astrophotography. In: Schielicke, Reinhard E. (ed.): Astronomische Gesellschaft - Abstract Series No. 14 (1998). Hamburg 1998, p. 80.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Astronomisches Mäzenatentum. Proceedings der Tagung an der Kuffner-Sternwarte in Wien, ,,Astronomisches Mäzenatentum in Europa’’, 7.--9. Oktober 2004. Norderstedt: Books on Demand (Nuncius Hamburgensis - Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; Band 11) 2008.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Cultural Heritage of Astronomical Observatories -- From Classical Astronomy to Modern Astrophysics. Proceedings of International ICOMOS Symposium in Hamburg, October 14--17, 2008. Berlin: hendrik Bäßler-Verlag (International Council on Monuments and Sites, Monuments and Sites XVIII) 2009.

Links to external sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 7

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-07-22 17:21:06

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

- Landessternwarte Königstuhl (LSW)

- Center for Astronomy (ZAH) at the University of Heidelberg

- Das Leuchten der Sterne fixiert -- Die historische Fotoplattensammlung der Landessternwarte Heidelberg-Königstuhl

- Zur Geschichte der Astronomie in der Kurpfalz, Förderkreis Landessternwarte Heidelberg e.V.

- Max Wolf, Bergfriedhof Heidelberg

- Max Wolf, Heidelberger Geschichtsverein e.V.

- Kleinplanetenentdeckungen in Heidelberg: Beobachtungen von Asteroiden haben in Heidelberg eine lange Tradition. Bis heute ist der Observatory Code 024 der Standort mit den meisten Nummerierungen in Deutschland.

- Privatsternwarte von Max Wolf in Heidelberg-Märzgasse

- Wolf, Maximilian (Max) Franz Joseph Cornelius, LEO-BW.de

- Gabriele Dörflinger: Märzgasse 16 - Max Wolf, Heidelberger Mathematiker Rundgang - Historia Mathematica Heidelbergensis

- Klaus Wenzel: Der Wolfsche Sechszöller -- Der Lebenslauf eines historischen Teleskops

- HDAP -- Heidelberg Digitized Astronomical Plates

- Milcho Tsvetkov: Wolf-Palisa Survey: The Wolf-Palisa stellar charts were produced between 1900 and 1916 in a collaboration between the Heidelberg and Vienna Observatories for the needs of minor planets observations.

Links to external on-line pictures - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-08-17 10:23:21

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

no information available

PrintPrint contents of 'Description' tab

(opens in a new window) Theme

Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Case Study Navigation

- InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 3

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-20 14:34:37

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Latitude 49°23’54’’ N, Longitude 08°43’29’’ E, Elevation 566m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 1

Status: PUB

Date: 2018-08-17 10:23:20

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

024

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 16

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-05-25 18:42:01

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 1a. Laboratory of Kirchhoff and Bunsen (1858), Hauptstr. 52 (DChG)

Fig. 1b. Laboratory of Kirchhoff and Bunsen (1858), "Haus zum Riesen", Johann Adam Breunig (1707/08), Hauptstr. 52 (Wikipedia)

In Heidelberg, the method of spectral analysis was invented by Kirchhoff and Bunsen (1859); their Laboratory was since 1868 in the "Haus zum Riesen", Johann Adam Breunig (1707/08), Hauptstr. 52.

Max Wolf’s private observatory, Märzgasse 16

Fig. 2a. Max Wolf’s birthplace, Märzgasse 16 (Wikipedia, CC4, Ribax)

Fig. 2b. Max Wolf’s private observatory, Märzgasse 16 (1885), (Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Heid. Hs. 3695/B,5, Nachlass Max Wolf 0179)

Fig. 2c. Max Wolf’s private observatory, Märzgasse 16 (1885), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 2d. 6-inch-Astrograph - two portrait cameras (1892/93) in the white dome in Königsstuhl (Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Heid. Hs. 3695)

Fig. 2e. Max Wolf’s private observatory, 6-inch-Double Astrograph, consisting of two portrait cameras, made by Voigtländer of Braunschweig (1892), now as a museum object in Heidelberg-Königsstuhl Observatory (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Max Wolf’s birthplace, built in 1836, and private observatory (1885) can be found in Märzgasse 16 in Heidelberg.

The double astrograph was put into operation by Max Wolf in February 1892. The astrograph consisted of two 6-inch-portrait lenses made by Voigtländer of Braunschweig. They had an aperture ratio of f/5. The field of view was approximately 70 square degrees and thus covered an unusually large section of the sky for that time. The guiding telescope was used for tracking during the recordings. With this instrument, Max Wolf discovered, among other things, the North American nebula NGC7000 and many new minor planets (planetoids, asteroids). Minor planets revealed themselves on the exposed photographic plates by small traces of lines, due to their own motion during the relatively long exposure time, which could well be a few hours.

Wolf’s instruments, the double astrograph, consisting of two portrait cameras and a guiding telescope, are preserved in Heidelberg-Königsstuhl Observatory.

Großherzogliche Bergsternwarte / Landessternwarte Heidelberg

Fig. 3. Heidelberg Observatory (LSW, Uni HD)

Fig.: Heidelberg Observatory (LSW, Uni HD)

Thanks to the activity of Grand Duke Friedrich I of Baden (1826--1907), the Heidelberg State Observatory (Großherzogliche Bergsternwarte, later: Landessternwarte Heidelberg) was built on the Königstuhl (elevation 566m). On June 20, 1898, the Grand Ducal Mountain Observatory on the Königstuhl was inaugurated in the presence of the Grand Duke Friedrich I of Baden. Heidelberg was one of the first mountain observatories in Europe after Nice Observatory and comparable to the American mountain observatories like Lick.

First light on the Königsstuhl was on June 28, 1898.

Fig. 4. Map of Heidelberg Observatory (LSW, Uni HD)

There were two scientific departments: The Astrometric Institute with the meridian instruments and slits (East Institute), headed by Karl Valentiner (1845--1931) and the Astrophysical Institute (West Institute) under Max Wolf. After Valentin’s retirement (1909), Max Wolf headed the entire institute.

The original instrumentation of Heidelberg Observatory came from Mannheim Observatory, founded in 1774, which had been relocated to Karlsruhe in 1880 due to the increasing deterioration of observation conditions.

Fig. 5. Entrance gate of Heidelberg Observatory (© Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

With the main instruments, the Bruce astrograph (August 16, 1900) and the Waltz reflector (1906) -- both financed by private foundations -- the institute was one of the most modern research facilities in the world at the time.

Max Wolf (1863--1932)

Fig. 6. Max Wolf (1863--1932), (Wikipedia)

Maximilian Franz Joseph Cornelius Wolf (1863--1932) studied physics as scholar of Georg Hermann Quincke (1834--1924) in Heidelberg, astronomy in Strasbourg, and did his doctorate in Heidelberg under the mathematician Leo Königsberger (1837--1921). Max Wolf initiated astrophysics in Heidelberg at the end of the 19th century, especiallly as a pioneer of photography. While still a student, he discovered in his private observatory the periodic comet 14P/Wolf, named after him.

Since 1893 Wolf was an associate professor at Heidelberg University. He turned down appointments to Göttingen and Vienna university Observatories. The astronomical institute initially consisted of two competing departments, the astrophysical under Max Wolf and the astrometric under Wilhelm Valentiner (1845--1931), who was first director in Mannheim and from 1880 to 1909 director of Karlsruhe Observatory. But after Valentin’s retirement in 1909, the departments were merged under the direction of Max Wolf until 1932.

Fig. 7a. North America Nebula NGC 7000 in the constellation Cygnus (1891), 13 hours exposure time (Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Wolf 1925, 0035)

Fig. 7b. Types of nebulae, defined by Max Wolf in 1908 (LSW Heidelberg)

The celestial photography developed by Max Wolf made epochal discoveries possible, such as that of the North America Nebula in the constellation Cygnus (1891), the rediscovery of Halley’s Comet (1909), numerous variable stars are found, studies of the tail structure and spectra brought new knowledge about comets, followed by studies of the structure of the Milky Way system. Large nebulae in the constellations Orion, Cygnus and Auriga are discovered on photographic plates. Spectra reveal that "nebulae" are gas structures like Huggins had already proposed in 1864. For his remarkable photographic recordings, Wolf was awarded with gold medals at the world exhibitions in Paris (1900) and St. Louis (1904).

Fig. 8. Max Wolf’s Spectrum of the Andromeda nebula (1911), 25 hours exposure time (Sitzungsberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften, Math.-Naturwiss. Klasse, Abt. A, 1912)

In spiral nebulae like Andromeda, recognized by Julius Scheiner (1858-1913) as stellar system outside of our Milky Way, the systematic shift in the spectral lines was recognized by Max Wolf (1913). Wolf developed the blink comparator together with Carl Pulfrich (1858--1927) from the Zeiss company. By quickly comparing two photo plates, changes in positions are obvious and thus comets and asteroids could be discovered, in addition, variable stars could be recognized due to the blinking effect. Wolf discovered ten novae in this way.

Fig. 9a. Blink comparator, Carl Zeiss of Jena (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 9b. Comet Morehouse (1908), Stereoscopic images (1913) (LSW Heidelberg)

Fig. 9c. Asteroid (323) Brucia, the first asteroid, discovered by Max Wolf using the photographic method in 1891, model, Haus der Astronomie (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Up until the 1950s, the emphasis of Max Wolf’s research was concentrated on asteroids: around 800 were discovered on photographic plates in the Königstuhl Observatory by Max Wolf and his cooperators, including the first Jupiter Trojan Asteroid 588 Achilles in 1906.

The asteroid (323) Brucia, discovered by Max Wolf on December 22, 1891, was the first asteroid using the photographic method, and the lunar crater Bruce were named in memory of the donation of the Bruce Reflector by Catherine Wolfe Bruce (1816--1900).

Fig. 10. Catherine Wolfe Bruce (1816--1900), (Wikipedia)

History - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 10

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-15 18:37:22

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

Fig. 11. Six domes of Heidelberg Observatory (Wikipedia, CC3, Mhdman)

In 1898, the "Großherzogliche Bergsternwarte" (Grand Ducal Mountain Observatory) was inaugurated by Grand Duke Friedrich I of Baden.

Fig. 12a. Kann Refractor Building (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12b. 8-inch-Kann Refractor, Merz of Munich (Photo: Werner Zigs)

Fig. 12c. Bruce-Telescope Dome (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12d. 40-cm-Bruce photographic double refractor (1900), 1900 -- donated by Catherine Wolfe Bruce (1816--1900) of New York (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12e. 40-cm-Bruce double astrograph (1900), 1900 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12f. 40-cm-Bruce double astrograph (1900), 1900 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12g. Zeiss-Telescope Building (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12h. Waltz-Telescope Building - just in restoration (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12i. 72cm-Waltz-Telescope (Newton), Nasmyth-Focus, Carl Zeiss of Jena (1906) (LSW Heidelberg)

Instruments

- 6-inch-Refractor (1859), used for the visual observation of double stars, later was used until 1924 to measure star clusters like globular clusters, and then for teaching and training purposes; in 1957, the 6-inch-Refractor was donated to the public observatory in Karlsruhe.

- Max Wolf’s instrument from his private observatory: 6-inch-Double Astrograph, consisting of two portrait cameras, made by Voigtländer of Braunschweig (1892 and 1893), and a guiding telescope, Reinfelder & Hertel of Munich, on a German mounting, made by "M. Sendtner of Munich" in a 5-m-dome; he added also smaller objectives like 5-inch-Kranz and 61-mm-Steinheil. The 6-inch-astrograph was used on Königsstuhl from 1898 until 1960, first in a white dome, then since 1919 in a black dome. The last photographic plate was exposed on June 16, 1939, for 4 minutes, it showed the variable star P Cygni.

- 8-inch-Kann Refractor (20-cm diameter, 300-cm focal length), wooden tube, German mounting, Merz, Munich -- the oldest telescope of the Landessternwarte, already mentioned in the annual report of 1894 of the Karlsruhe Observatory, donated by L. Kann.

- 40-cm-Bruce-Telescope (16-inch, focal length 2m), a photographic double refractor (astro camera), diameter of the photographic lenses 40-cm, visual guiding telescope (objective diameter 25-cm, focal length 4-m), first light August 1900 -- donated by Catherine Wolfe Bruce (1816--1900) of New York. Thousands of photographic plates were taken with this astrograph.

- 72cm-Waltz-Telescope (Newton), Nasmyth-Focus, Carl Zeiss of Jena (1906) with a two-prism-Spectrograph.

It was the first "large" reflector, made by Carl Zeiss of Jena; shortly afterwards, 1911, the Hamburg 1-m-Reflector was built.

- Schmidt telescope (main mirror diameter 40-cm, diameter of the correction plate 25-cm, focal length 90-cm (f:3.6), produced in the Heidelberg workshop (1963), large field of view (4°), used with objective lens prism

- 50-cm-Cassegrain Reflector, main mirror diameter 50-cm, focal length 6.95-m (f:14), produced in the Heidelberg workshop (1978), used for stellar photometry and polarimetry.

Until 1978, a 12-inch-refractor (4.22-m focal length), Steinheil, donated by Kreßmann, was used as guiding telescope.

- 75-cm Ritchey-Chretien-Cassegrain-Telescope (focal length 6-m, f:8), Carl Zeiss of Oberkochen (1977), used with CCD, used since 2005 in the ATOM-Project in Namibia

- 70-cm Cassegrain Reflecting telescope (focal length 5.6-m, f:8), (1988), used with CCD camera.

- Stereokomparator, Carl Zeiss of Jena

- Pendulum clocks: Chronometerwerke GmbH, Ferdinand Dencker, No. 52 (sidereal time), S. Riefler, No. 44, Munich (1899), Clemens Riefler, No. 523, Munich (1928)

Fig. 13a. Main Building (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13b. Waltz Reflector building and memorial plaque Max Wolf (1953), (Photo: Dietrich Lemke)

Fig. 13c. Zeiss Telescope Building and Bruce Dome (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13d. East Institute and Schmidt Telescope dome and two Cassegrain domes (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13e. East Institute and Cassegrain dome (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13f. Pendulum clock Chronometerwerke GmbH, Ferdinand Dencker, No. 52 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13g. Pendulum clock S. Riefler, No. 44, Munich (1899), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 13h. Pendulum clock Clemens Riefler, No. 523, Munich (1928), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

After Wolf’s death (1932), the theorical astronomer Heinrich Vogt (1890--1968) was entrusted with the management of the observatory. His research was in stellar structure (Vogt-Russell-Theorem). In 1931, he became a member of the NSDAP, and in 1933, he became a member of the SA (Obersturmführer). In 1933, he got the call as full professor at the University of Heidelberg.

August Kopff (1882--1960), a former student of Max Wolf and director of the Astronomical Computing Institute (Astronomisches Recheninstitut, ARI), 1924 to 1954 in Berlin, and since 1945 in Heidelberg, took over the management of Heidelberg Observatory. He discovered Kopff’s comet in 1906 (rendezvous of the Galileo space probe), and 66 asteroids in the period from 1905 to 1909. But he was already in the 1920s interested in the General Theory of Relativity, gave lectures and published a textbooks.

Fig. 14a. Hans Kienle (1895--1975), (Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg)

Fig. 14b. Happel Laboratory for Astrophysics (1957), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Hans Kienle (1895--1975) was professor and director in Göttingen from 1924/25, director of the Astrophysical Observatory in Potsdam. In 1950 Kienle he got the call as professor for astrophysics and astronomy at the University of Heidelberg and director of the State Observatory Heidelberg-Königstuhl. There he erected the Happel Laboratory for Astrophysics (1957), north of the main building, financed by a foundation of the Heidelberg painter Karl Happel (1819--1914), with a "black body" in order to investigate the energy distribution in the spectra of the Sun and stars, with the aim of determining an absolute temperature scale of the stars (absolute spectrophotometry). Today instruments for international observatories like ESO are developed here. After his retirement in 1962, Kienle accepted an invitation from former students to Turkey in order to help building a new observatory in Izmir.

Hans Elsässer (1929--2003), after studying at the University of Tübingen (Habilitation 1959), worked at the Swiss Jungfraujoch Observatory and at the Boyden Observatory in Bloemfontein in South Africa. From 1955 to 1956 Elsässer was on seeing expeditions in South Africa, intergrated in the plan for the ESO Southern Observatory. In 1962 he became a full professor for astronomy at the University of Heidelberg, and he was also head of the State Observatory in Heidelberg-Königstuhl until 1975. In 1968, Elsässer was the founding director of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg. He remained Managing Director of the MPI until 1997. Elsässer was involved in various rocket and balloon experiments that were necessary for the successful implementation of the Helios A and B and the Infrared Space Observatory (ISO) projects. He was interested in topics like interstellar matter, star formation, active galaxies, and large-scale structures in the universe.

Directors

- Maximilian Franz Joseph Cornelius Wolf (1863--1932), 1898 to 1932

- Heinrich Vogt (1890--1968), 1933 to 1945

- August Kopff (1882--1960), 1947 to 1950

- Hans Kienle (1895--1975), 1950 to 1962

- Hans Elsässer (1929--2003), 1962 to 1975

- Immo Appenzeller (*1940), 1975 to 2005

- Andreas Quirrenbach, since 2006

State of preservation - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 4

Status: PUB

Date: 2022-03-15 18:18:04

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The observatory is in good condition and still in active use.

There was no prominent architect involved in erecting the buildings.

The old meridian circle building, the East Institute of the observatory, was converted into an auditorium building in the 1960s,

which today also houses a small astronomical museum, where also the photographic plate archive can be found today.

Comparison with related/similar sites - InfoTheme: Astronomy from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century

Entity: 141

Subentity: 1

Version: 6

Status: PUB

Date: 2021-11-21 02:33:56

Author(s): Gudrun Wolfschmidt

The layout as an astronomy park is similar to Hamburg Observatory, but smaller; the strict separation like in Hamburg Observatory of the observing buildings (domes) on one side and of the office buildings, apartments, workshops on the other side is not so strict in Heidelberg, e.g. the Bruce telescope is in close connection to the main office building, another dome is on the Eastern Institute.